Reading Isaiah Berlin in China1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Politics Seriously – but Not Too Seriously

Taking Politics Seriously – but Not Too Seriously Charles Blattberg Professor of Political Philosophy Université de Montréal It makes one ashamed that men of our advanced years should turn a thing as serious as this into a game. Seneca1 One of Edward’s Mistresses was Jane Shore, who has had a play written about her, but it is a tragedy & therefore not worth reading. Jane Austen2 To Isaiah Berlin, the idea “that all good things must be compatible…and perhaps even entail one another in a systematic fashion [is] perhaps one of the least plausible beliefs ever entertained by profound and influential thinkers.”3 So says pluralism of monism. The claim is meant to apply as much to personal as to political life, and it has led pluralists to argue that monists overlook the inescapably tragic dimension of both. If, when values conflict, we cannot turn to a systematic theory for guidance, then it seems we have no choice but to compromise and, by compromising, diminish what we believe to be good. That, at least, is what comes from negotiation, which is what pluralists recommend as the chief alternative to the application of monist theories of morality or justice. And they do so even though – or rather because – it means embracing a world that is inherently unsystematic, sometimes tragically so.4 One might push this point even further. Monists do not merely fail to give the tragedy of morals or politics its due; some can even be accused of treating them frivolously, as if they were *A chapter from Towards One, As Many (forthcoming). -

What the Book Contains Is a Theory of the Nature of Philosophy. Philosophy Is an Unstable Derived Cultural Activity Like the Opera

The Philosophical Inquiry: Towards a Global Account, was published by the University Press of America, Langham, 2002) What the book contains is a theory of the nature of philosophy. Philosophy is an unstable derived cultural activity like the opera. It takes its materials, motivations and procedures from three different cultural fields: art, religion, and science, with different polarizations according to the author or the tradition. As philosophy is the cradle of sciences, they dictate the direction, and by opposing Science from philoophy the most proper nature of Science i salso uncovered. As I published this book as I was in Berkeley 18 years ago it was a death-born child. There were no reviews, no nothing. Anyway, I cannot deny that in my view it still gives the best explanation of the nature of philosophy I’ve already met. THE PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY TOWARDS A GLOBAL ACCOUNT ____________________ _________ CLAUDIO COSTA THE PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY * (Heraklit) Nun scheint mir, gibt es ausser der Arbeit des Kunstlers noch eine andere, die Welt sub specie aeterni einzufangen. Es ist – glaube ich, der Weg des Gedankens, der gleichsam über die Welt hinfliege und sie so lässt, wie sie ist – sie von oben von Fluge betrachtend.** (Wittgenstein) Science is what we know; philosophy is what we don’t know. (…) Science is what we can prove to be true; philosophy is what we can’t prove to be false. (B. Russell) _____________ * The sibyl with raving mouth uttering her unlaughing, unadorned, unincensed words reaches out over a thousand years with her voice through the god. (tr. K. -

The Development of Ideas in the Novels of Iris Murdoch Thesis

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Playful Platonist : The development of ideas in the novels of Iris Murdoch Thesis How to cite: Edwards, S. L. (1984). Playful Platonist : The development of ideas in the novels of Iris Murdoch. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000de3e Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk i U is 154,6 (Z ý', 1)P, S-f P. ýC- -1 LO PLAYFUL PLATONIST: TFIE DEVELOPISNT OF =Eý 221 TFIE NOVELS OF IRTI; MURDOCH by Stephen Laurence Edwards A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph. D. at The Open University, January 1984. rio u0 I- Playful tlatonist: the Development of Ideas in the Novels of Iris Mirdoch I am willing that this thesis may be made available to readers and may be photcopied subject to the discretion of the Librarian. L S. L. Edwards 20th June 1984. Th, opiýn t-lrivp-rsifm col, 22 ... ..... ...... ii SUýRARY Tnis thesis examines Iris Murdoch's novels in the light of her philosophical thinking. 1t places her ethical thinking in the context of twentieth century moral philosophy and shows that her approach to the problems of the subject is out of key with the general run of cont(-, r,..pora-ry philosophical th-inking. -

1.9 Andreas Vrahimis

Journal for the History of “Was There a Sun Before Men Existed?” Analytical Philosophy A.J. Ayer and French Philosophy in the Fifties Volume 1, Number 9 Andreas Vrahimis In contrast to many of his contemporaries, A. J. Ayer was an ana- Editor in Chief lytic philosopher who had sustained throughout his career some Mark Textor, King’s College London interest in developments in the work of his “continental” peers. Ayer, who spoke French, held friendships with some important Parisian intellectuals, such as Camus, Bataille, Wahl and Merleau- Editorial Board Ponty. This paper examines the circumstances of a meeting be- Juliet Floyd, Boston University tween Ayer, Merleau-Ponty, Wahl, Ambrosino and Bataille, which Greg Frost-Arnold, Hobart and William Smith Colleges took place in 1951 at some Parisian bar. The question under dis- Ryan Hickerson, University of Western Oregon cussion during this meeting was whether the sun existed before Henry Jackman, York University humans did, over which the various philosophers disagreed. This Sandra Lapointe, McMaster University disagreement is tangled with a variety of issues, such as Ayer’s Chris Pincock, Ohio State University critique of Heidegger and Sartre (inherited from Carnap), Ayer’s Richard Zach, University of Calgary response to Merleau-Ponty’s critique of empiricism, and Bataille’s response to Sartre’s critique of his notion of ‘unknowing’, which Production Editor uncannily resembles Ayer’s critique of Sartre. Amidst this tangle Ryan Hickerson one finds Bataille’s statement that an “abyss” separates English from French and German philosophy, the first recorded an- Editorial Assistant nouncement of the analytic-continental divide in the twentieth century. -

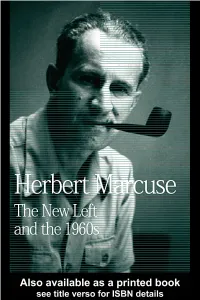

THE NEW LEFT and the 1960S COLLECTED PAPERS of HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED by DOUGLAS KELLNER

THE NEW LEFT AND THE 1960s COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three THE NEW LEFT AND THE 1960s Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA HERBERT MARCUSE (1898–1979) is an internationally renowned philosopher, social activist and theorist, and member of the Frankfurt School. He has been remembered as one of the most influential social critical theorists inspiring the radical political movements in the 1960s and 1970s. Author of numerous books including One-Dimensional Man, Eros and Civilization, and Reason and Revolution, Marcuse taught at Columbia, Harvard, Brandeis University and the University of California before his death in 1979. DOUGLAS KELLNER is George F. Kneller Chair in the Philosophy of Education at U.C.L.A. He is author of many books on social theory, politics, history and culture, including Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism, Media Culture and Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity. His Critical Theory and Society: A Reader, co-edited with Stephen Eric Bronner, and recent book Media Spectacle, are also published by Routledge. THE NEW LEFT AND THE 1960s HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Three Edited by Douglas Kellner First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004 © 2005 Peter Marcuse Selection, editorial matter and introduction © 2005 Douglas Kellner Preface © 2005 Angela Y. -

From Hobbes to Habermas: the Anti-Cultural Turn in Western Political Thought

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Political Science Political Science 2020 FROM HOBBES TO HABERMAS: THE ANTI-CULTURAL TURN IN WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT Ralph Gert Schoellhammer University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7011-6696 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.313 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Schoellhammer, Ralph Gert, "FROM HOBBES TO HABERMAS: THE ANTI-CULTURAL TURN IN WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT" (2020). Theses and Dissertations--Political Science. 32. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/polysci_etds/32 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Political Science by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Biblio.Doc, November 10, 2008 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY JOHN

Biblio.doc, November 10, 2008 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY JOHN R. SEARLE 1956 (1) "Does It Make Sense to Suppose that All Events, Including Personal Experiences, Could Occur in Reverse?", Analysis Competition - Ninth ‘Problem’, Analysis, Vol. 16, No. 6, New Series No. 54, June 1956. 1958 (2) "Proper Names", Mind, Vol. LXVII, April, 1958. Reprinted in: Philosophy and Ordinary Language, Charles E. Caton (ed.), Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963. Readings in the Philosophy of Language, Jay P. Rosenberg, and Charles Travis (eds.), Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1971. Philosophical Logic, P. F. Strawson (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967. Praesuppositionen in Philosophie und Linguistik, J.S. Petoefi and D. Franck (eds.), Frankfurt am Main: Athenaeum 1973. Causal Theories of Mind, Steven Davis (ed.), Berlin: Walter de Gruyter: 1983. The Philosophy of Language, A. P. Martinich (ed.), Oxford: 2 Biblio.doc November 10, 2008 Oxford University Press, 1985. Translations: French: "Les Noms Propres", Theories du Signe et du Sens, Alain Rey (ed.), Paris: Klinksieck 1973 - 1976. German: "Eigennamen", Philosophie und Normale Sprache, Eike von Savigny (ed.), Freiburg: Verlag Karl Alber, 1969. Reprinted in: Philosophie und Sprache, Joachim Schulte (ed.) Stutttgart: Philipp Reclam, jun., 1981. Italian: "Nomi Propri", La Struttura Logica del Linguaggio, Andrea Bonomi (ed.), Milano: Valentino Bompiani, 1973. Spanish: "Nombres Propuis y Descripciones", in: La busqueda del significado, Luis Ml. Valdes Villanueva (ed.), Madrid: Universidad de Murcia, Tecnos, 1991. Chinese: in A.P. Martinich, The Philosophy of Language, 1998. (3) "Russell's Objections to Frege's Theory of Sense and Reference," Analysis, 18, 1957-8. Reprinted in: Essays on Frege, E. -

Charles Taylor's Answer To

BETWEEN EMPIRICISM AND INTELLECTUALISM: CHARLES TAYLOR’S ANSWER TO THE ‘MEDIA WARS’ Marc Anthony Caldwell Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Centre for Cultural and Media Studies, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. Durban, December 2008 Declaration I declare this dissertation is my own unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities, Development and Social Science, in the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. Marc Anthony Caldwell December, 2008 ii Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………… iv Abstract ………………………………………………………………. v Introduction …………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One: Science Wars, Post-Marxism, Taylor ………………………….. 18 Chapter Two: Journalism and the Media Wars ……………………………….. 48 Chapter Three: Taylor’s philosophical anthropology ……………………………. 78 Chapter Four: Taylor and the New Left ………………………………………. 119 Chapter Five: Merleau-Ponty’s influence on Taylor’s reading Marx …………. 159 Chapter Six: Taylor’s anti-epistemology …………………………………. 191 Conclusion …………………………………………………………… 227 References …………………………………………………………… 247 iii Acknowledgements My thanks go to my ‘thesis-widowed’ wife, Adi, who patiently read through the final drafts. Thanks too, to my supervisor, Professor Keyan Tomaselli, for remaining confident that despite its multiple versions, a final version of this thesis would eventually emerge. iv Abstract When the Media Wars broke out in Australian universities in the mid-1990s, journalism educator Keith Winschuttle accused cultural studies of teaching theory that contradicted the realist and empirical worldview of journalism practice. He labeled cultural studies as a form of linguistic idealism. His own worldview is decidedly empiricist. -

A Critical Examination of the Underlying Sociological Theory of Secularization in the West in the Work of Charles Taylor

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Critical Examination of the Underlying Sociological Theory of Secularization in the West In the Work of Charles Taylor A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By German F. McKenzie Washington, D.C. 2015 A Critical Examination of the Underlying Sociological Theory of Secularization in the West In the Work of Charles Taylor German F. McKenzie, Ph.D. Director. William E. Dinges, Ph.D. Scholarly debate on secularization in the West has been largely developed in sociological terms. Two extreme positions in the conversations are those I label as “orthodox” and “counter- orthodox”, with several authors taking middle stances. “Orthodox” theorists affirm that modernity necessarily erodes religion, whereas “counter-orthodox” ones —also known as Rational Choice Theorists (RCT)— see secularization as a self-limiting process within modernity. As the debate between these views has somewhat stalled, other perspectives have caught the interest of researchers. An important contribution among them is that made by Canadian thinker Charles Taylor in his book A Secular Age (2007). This dissertation analyses the sociological basis of Charles Taylor’s account of secularization in order to elucidate what new insights he brings to the debate on the issue. It relies on textual analysis of all the pertinent works by Taylor, as well as his classical and contemporary sociological influences. As a sociological framework, it relies on the scholarship of British sociologist Margaret Archer, particularly on her views about the relationship between social and cultural structures and human agency, as well as about social change. -

Hart's Definition and Theory in Jurisprudence Again Robert Birmingham University of Connecticut School of Law

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Faculty Articles and Papers School of Law 1984 Hart's Definition and Theory in Jurisprudence Again Robert Birmingham University of Connecticut School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Birmingham, Robert, "Hart's Definition and Theory in Jurisprudence Again" (1984). Faculty Articles and Papers. 67. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_papers/67 +(,121/,1( Citation: 16 Conn. L. Rev. 775 1983-1984 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 15 16:44:04 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0010-6151 HART'S DEFINITION AND THEORY IN JURISPRUDENCE AGAIN by Robert Birningham* I will say what Hart's classic paper' means in, or translate it into, contemporary philosophical discourse. But to give a context for it, I start by talking about MacCormick's recent book, H.L.A. Hart.2 We come away from reading its introductory chapter, a chapter Summers calls "fascinating,"13 having learned that Hart was trained not as a le- gal philosopher or jurisprude as such but as a lawyer and separately as a philosopher. -

Supplementary Letters 1975–1997

Supplementary Letters 1975–1997 This PDF is one of a series designed to assist scholars in their research on Isaiah Berlin, and the subjects in which he was interested. The series will make digitally available both selected published items and edited transcripts of unpublished material. The PDF is posted by the Isaiah Berlin Legacy Fellow at Wolfson College, with the support of the Trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust. All enquiries, including those concerning rights, should be directed to the Legacy Fellow at [email protected] Supplementary Letters 1975–1997 Most of these letters do not appear in Affirming: Letters 1975–1997, being later discoveries. More annotation may be provided later, but for now the texts are made available here for the convenience of readers. Abbreviations and other editorial apparatus follow the conventions adopted in the published volume, including those listed here. Some sources are given at the end of the PDF, except for those to Robert Silvers, which are from the New York Public Library, MssCol 23385, Series I: Robert B. Silvers Files 1955–2016. Thanks to Richard Davenport-Hines, David Herman, Tal Nadan and Wang Qian for their help. The letters to Silvers are included by courtesy of the Manuscripts and Archives Division, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Those marked § first appeared in ‘The Israel Letters’, Jewish Quarterly no. 244, May 2021, 67–87. We are indebted to David Herman, who edited that selection, for allowing us to plagiarise his notes. Two (asterisked) letters from the published volume are also included: one because only a carbon copy was available to the editors (since then a top copy has come to light, and manuscript additions made by Berlin are shown here in this green); the other because the question arose on social media of what had been cut from it. -

Strategic Management Research in the Age of Post-Positivist Turmoil in the Social Sciences: Rigor Or Rigor Mortis?

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN BOOKSTACKS E'^-3 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/strategicnianagenn1291stub BEB "•^ilBSSBSS^ FACULTY WORKING PAPER NO. 1291 Strategic Management Research in the Age of Post-Positivist Turmoil in the Social Sciences: Rigor or Rigor Mortis? Charles I. Stubbart College of Commerce and Business Administration Bureau of Economic and Business Research University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign I a. BEBR FACULTY WORKING PAPER NO. 1291 College of Commerce and Business Administration University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign September 1986 Strategic Management Research in the Age of Post-Positivist Turmoil in the Social Sciences: Rigor or Rigor Mortis? Charles I. Stubbart, Visiting Assistant Professor Department of Business Administration I thank Linda Smircich, Marta Calas, Paul Shrivastava, Philippe Daudi, and Irene Duhaime for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. ABSTRACT This paper discusses the future of strategic management research. It begins with a short review of the present status of strategic management as a social science, and finds that little progress has l:)een made. But, this lack of progress is typical of social sciences. Logical positivism^ *lwcjii serves as the epistemological justification for most research in strategy. The paper explains why logical positivism failed. In the second part of the paper, I offer alternatives to logical positivism: critical theory, interpretation, and post-structuralism. The overall theme of the paper is that changing ideas of language and representation have made the traditional stance to strategic management research obsolete. I. INTRODUCTION Strategy scholars engage in many internecine debates.