Supplementary Letters 1975–1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading Isaiah Berlin in China1

Reading Isaiah Berlin in China1 A year before his death in 1997, Isaiah Berlin was invited by a Chinese scholar named Ouyang Kang to write a summary of his thought for the Chinese reading public. Berlin, as Dr Henry Hardy recalls, much valued this new readership, and therefore wrote his last essay, ‘My Intellectual Path’. It was first published in English in the New York Review of Books, and then included in The Power of Ideas, an anthologies edited by Hardy.2 Eight years later, this piece finally received its Chinese translation. According to Ouyang Kang, his incentive is to edit a book composed of intellectual self-portraits by several distinguished Anglophone philosophers as a way to introduce contemporary Anglophone philosophy to common readers in China. Ironically, when Ouyang’s volume was published, many of Berlin’s writings had already been translated and his thought been made accessible to the general public.3 Unlike his Oxford colleague, the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, Isaiah Berlin never went to China; nor did he write anything directly related to it. Although he sometimes mentioned China in passing, he seemed not to have known much about either its history or its status quo, and he probably viewed it, along with India and Japan, as an old, mysterious and exotic civilisation. Among his interlocutors, Joseph Alsop had served in the ‘Flying Tigers’ commanded by C.L. Chennault in fighting the Japanese. After the Communist Party took power by defeating Chiang Kai-shek’s army in 1949, thus ending a civil war lasted for three years, China became a Communist regime, which borrowed its totalitarian system entirely from the Soviet Union. -

Taking Politics Seriously – but Not Too Seriously

Taking Politics Seriously – but Not Too Seriously Charles Blattberg Professor of Political Philosophy Université de Montréal It makes one ashamed that men of our advanced years should turn a thing as serious as this into a game. Seneca1 One of Edward’s Mistresses was Jane Shore, who has had a play written about her, but it is a tragedy & therefore not worth reading. Jane Austen2 To Isaiah Berlin, the idea “that all good things must be compatible…and perhaps even entail one another in a systematic fashion [is] perhaps one of the least plausible beliefs ever entertained by profound and influential thinkers.”3 So says pluralism of monism. The claim is meant to apply as much to personal as to political life, and it has led pluralists to argue that monists overlook the inescapably tragic dimension of both. If, when values conflict, we cannot turn to a systematic theory for guidance, then it seems we have no choice but to compromise and, by compromising, diminish what we believe to be good. That, at least, is what comes from negotiation, which is what pluralists recommend as the chief alternative to the application of monist theories of morality or justice. And they do so even though – or rather because – it means embracing a world that is inherently unsystematic, sometimes tragically so.4 One might push this point even further. Monists do not merely fail to give the tragedy of morals or politics its due; some can even be accused of treating them frivolously, as if they were *A chapter from Towards One, As Many (forthcoming). -

Philosophy of Power and the Mediation of Art:The Lasting Impressions of Artistic Intermediality from Seventeenth Century Persia to Present Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2018 Philosophy of Power and the Mediation of Art:The Lasting Impressions of Artistic Intermediality from Seventeenth Century Persia to Present Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic PHILOSOPHY OF POWER AND THE MEDIATION OF ART: THE LASTING IMPRESSIONS OF ARTISTIC INTERMEDIALITY FROM SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PERSIA TO PRESENT Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy May, 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Ali Anooshahr, Ph.D. Professor, Department of History University of California, Davis Committee Member: Christopher Yates, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Philosophy, and Art Theory Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: EL Putnam, Ph.D. Assistant Lecturer, Dublin School of Creative Arts Dublin Institute of Technology ii © 2018 Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii “Do we need a theory of power? Since a theory assumes a prior objectification, it cannot be asserted as a basis for analytical work. But this analytical work cannot proceed without an ongoing conceptualization. And this conceptualization implies critical thought—a constant checking.” — Foucault To my daughter Ariana, and the young generation of students in the Middle East in search of freedom. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to a number of people, without whose assistance and support this dissertation project would not have taken shape and would not have been successfully completed as it was. -

What the Book Contains Is a Theory of the Nature of Philosophy. Philosophy Is an Unstable Derived Cultural Activity Like the Opera

The Philosophical Inquiry: Towards a Global Account, was published by the University Press of America, Langham, 2002) What the book contains is a theory of the nature of philosophy. Philosophy is an unstable derived cultural activity like the opera. It takes its materials, motivations and procedures from three different cultural fields: art, religion, and science, with different polarizations according to the author or the tradition. As philosophy is the cradle of sciences, they dictate the direction, and by opposing Science from philoophy the most proper nature of Science i salso uncovered. As I published this book as I was in Berkeley 18 years ago it was a death-born child. There were no reviews, no nothing. Anyway, I cannot deny that in my view it still gives the best explanation of the nature of philosophy I’ve already met. THE PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY TOWARDS A GLOBAL ACCOUNT ____________________ _________ CLAUDIO COSTA THE PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY * (Heraklit) Nun scheint mir, gibt es ausser der Arbeit des Kunstlers noch eine andere, die Welt sub specie aeterni einzufangen. Es ist – glaube ich, der Weg des Gedankens, der gleichsam über die Welt hinfliege und sie so lässt, wie sie ist – sie von oben von Fluge betrachtend.** (Wittgenstein) Science is what we know; philosophy is what we don’t know. (…) Science is what we can prove to be true; philosophy is what we can’t prove to be false. (B. Russell) _____________ * The sibyl with raving mouth uttering her unlaughing, unadorned, unincensed words reaches out over a thousand years with her voice through the god. (tr. K. -

In Search of the Sacred: a Conversation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought

In Search of the Sacred: A Conver- sation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought By Seyyed Hossein Nasr interviewed by Ramin Jahanbegloo Introduction by Terry Moore (Praeger, Santa Barbara, California, USA, 2010) Reviewed by M. Ali Lakhani eyyed Hossein Nasr requires no introduction Sto the readers of this journal. He is one of the foremost living intellectuals, a renowned scholar who has produced (and continues to produce) an impressive corpus of work in fields as diverse as Islamic studies, philosophy, science, history, art, architecture, and the environment, and is arguably the leading representative in the West of the peren- nial philosophy. He has made enormous contribu- tions to Islamic thought, to his own Iranian culture and heritage, and beyond these areas, to a universal humanistic thought rooted in Tradition—and for all of which he has been recognized by being the first non-European (and first Muslim) to deliver the famed Gifford lectures on theology at Edinburgh, the privilege of presenting the Cadbury lectures on the environment, and being only the 28th philosopher inducted by peer-recognition into the prestigious Library of Living Philosophers (along with such predecessors as Einstein, Russell, and Sartre). In fact, the volume on Nasr, published by the Library of Living Philosophers under the title “The Philosophy of Seyyed Hossein Nasr” (2001), contains both an intellectual autobiography of Nasr as well as a series of critical essays and responses, and so covers much of the same territory as the book under review. However, there are several reasons why a reader would also want to read In Search of the Sacred: A Conversation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought. -

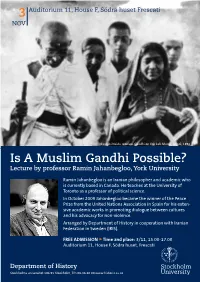

Is a Muslim Gandhi Possible? Lecture by Professor Ramin Jahanbegloo, York University

3 Auditorium 11, House F, Södra huset Frescati NOV Sarojini Naidu receives Gandhi on the Salt March, Dandi, 1930 Is A Muslim Gandhi Possible? Lecture by professor Ramin Jahanbegloo, York University Ramin Jahanbegloo is an Iranian philosopher and academic who is currently based in Canada. He teaches at the University of Toronto as a professor of political science. In October 2009 Jahanbegloo became the winner of the Peace Prize from the United Nations Association in Spain for his exten- sive academic works in promoting dialogue between cultures and his advocacy for non-violence. Arranged by Department of History in cooperation with Iranian Federation in Sweden (IRIS). FREE ADMISSION Time and place: 3/11, 15.00-17.00 Auditorium 11, House F, Södra huset, Frescati Department of History Stockholms universitet 106 91 Stockholm, Tfn 08-16 20 00 www.historia.su.se Is A Muslim Gandhi Possible? Lecture by professor Ramin Jahanbegloo, York University Stockholm University, House F, Auditorium 11 15:00–17:00 Ramin Jahanbegloo, born 1956 in Tehran, is a well-known Iranian-Canadian philosopher. He received his B.A. and M.A. in Philosophy, History and Political Science and later his Ph.D. in Philosophy from the Sorbonne University. In 1993 he taught at the Academy of Philosophy in Tehran. He has been a researcher at the French Institute for Iranian Studies and a fellow at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. Ramin Jahanbegloo taught in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto from 1997-2001. He later served as the head of the Department of Contemporary Studies of the Cultural Research Centre in Tehran and, in 2006-07, was Rajni Kothari Professor of Democracy at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi, India. -

The Influences of Jalal Al-Din Rumi in Seyyed Hossein Nasr’S Sufi Diagnosis of the Environmental Crisis

WHAT WAS SAID TO THE ROSE THAT MADE IT OPEN WAS SAID TO ME, HERE, IN MY CHEST: THE INFLUENCES OF JALAL AL-DIN RUMI IN SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR’S SUFI DIAGNOSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS BY CORY WENSLEY BA, St. Francis Xavier University, 2013 A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theology and Religious Studies January, 2015, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Cory Lee Wensley Approved: Dr. Syed Adnan Hussain Supervisor Approved: Dr. Anne Marie Dalton Examiner Approved: Dr. Linda Darwish Reader Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Genealogical Methodology ........................................................................................................... 10 Chapter One: Literature Review ................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Two: Jalal al-Din Rumi’s Understanding of the Natural Environment and Humanity’s Relationship with It ....................................................................................................................... 53 Chapter Three: Seyyed Hossein Nasr’s Sufi Diagnosis of the Environmental Crisis .................. 82 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. -

"As Long As We Remain Creative and Critical, There Will Be Hope"

"As long as we remain creative and critical, there will be hope" 07/18/2018 The Iranian thinker Ramin Jahanbegloo is a professor of political science at the University of Toronto and a leading expert in the political context of his country and in the philosophy of nonviolence, among other subjects. On July 5, he participated in the dialogue "A troubled world, where does it take us?" along with Rafael Bisquerra, Alfons Cornella, Sara Moreno and Carlota Pi. The event was organized by the Social Council of the UAB as part of the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the university. Many of his books are dialogues with other thinkers such as George Steiner or Isaiah Berlin. What is particular about dialogue as a way of transmitting knowledge? Dialogue has played a very important role in my philosophical thinking. The basis of the dialogue that I have established with people from different cultures has been mainly the Socratic dialogue. Perhaps you do not get definitive answers but aporias, as in the Platonic dialogues; what's really important are the questions. I was a student when I wrote those dialogue books with Steiner and Berlin, and then other shorter ones with Noam Chomsky, Jacques Derrida, Emmanuel Lévinas, Paul Ricoeur ... There were always questions in my mind and I looked for the answer in other people; but you never find the definitive answers because they do not exist. Questioning is the most important thing for humans: without questions, we have no freedom, and without freedom, we have no questions. In an article by him, published in El País , he said that Donald Trump's decision to withdraw from the nuclear agreement with Iran increases the danger of a war. -

Upgrading the Women's Movement in Iran

Upgrading the Women’s Movement in Iran: Through Cultural Activism, Creative Resistance, and Adaptability Meaghan Smead Samuels A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies University of Washington 2018 Committee: Kathie Friedman Sara Curran Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2018 Meaghan Smead Samuels 2 University of Washington Abstract Upgrading the Women’s Movement in Iran: Through Cultural Activism, Creative Resistance, and Adaptability Meaghan Smead Samuels Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kathie Friedman Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies The purpose of this research is to identify and analyze the effects of the 2009 post- election state crackdown on the Iranian Women’s Movement. Varying narratives of how the crackdown affected women’s activism necessitate a better understanding as to how this social movement negotiates periods of repression. An examination of accounts and actions by women in Iran reveal this Movement to be fluid, adaptable, and resilient, utilizing different structures, strategies and tactics depending on the current political environment. This study demonstrates the ability of Iranian women to develop creative solutions for public engagement in repressive moments, including through everyday acts of resistance and by practicing cultural activism. Women in Iran work to transform culture in order to impel the state to make changes to discriminatory laws. Prevailing social movement theories help to explain some characteristics of the Iranian Women’s Movement, but a more complex model is required to account for dynamic gendered social movements in non-Western, authoritarian contexts. -

The Impact of the Modernity Discourse on Persian Fiction

The Impact of the Modernity Discourse on Persian Fiction Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Comparative Studies in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Saeed Honarmand, M.A. Graduate Program in Comparative Studies The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Richard Davis, Advisor Margaret Mills Philip Armstrong Copyright by Saeed Honarmand 2011 Abstract Modern Persian literature has created a number of remarkable works that have had great influence on most middle class people in Iran. Further, it has had representation of individuals in a political context. Coming out of a political and discursive break in the late nineteenth century, modern literature began to adopt European genres, styles and techniques. Avoiding the traditional discourses, then, became one of the primary characteristics of modern Persian literature; as such, it became closely tied to political ideologies. Remarking itself by the political agendas, modern literature in Iran hence became less an artistic source of expression and more as an interpretation of political situations. Moreover, engaging with the political discourse caused the literature to disconnect itself from old discourses, namely Islamism and nationalism, and from people with dissimilar beliefs. Disconnectedness was already part of Iranian culture, politics, discourses and, therefore, literature. However, instead of helping society to create a meta-narrative that would embrace all discourses within one national image, modern literature produced more gaps. Historically, there had been three literary movements before the modernization process began in the late nineteenth century. Each of these movements had its own separate discourse and historiography, failing altogether to provide people ii with one single image of a nation. -

The Development of Ideas in the Novels of Iris Murdoch Thesis

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Playful Platonist : The development of ideas in the novels of Iris Murdoch Thesis How to cite: Edwards, S. L. (1984). Playful Platonist : The development of ideas in the novels of Iris Murdoch. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c [not recorded] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000de3e Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk i U is 154,6 (Z ý', 1)P, S-f P. ýC- -1 LO PLAYFUL PLATONIST: TFIE DEVELOPISNT OF =Eý 221 TFIE NOVELS OF IRTI; MURDOCH by Stephen Laurence Edwards A thesis submitted for the degree of Ph. D. at The Open University, January 1984. rio u0 I- Playful tlatonist: the Development of Ideas in the Novels of Iris Mirdoch I am willing that this thesis may be made available to readers and may be photcopied subject to the discretion of the Librarian. L S. L. Edwards 20th June 1984. Th, opiýn t-lrivp-rsifm col, 22 ... ..... ...... ii SUýRARY Tnis thesis examines Iris Murdoch's novels in the light of her philosophical thinking. 1t places her ethical thinking in the context of twentieth century moral philosophy and shows that her approach to the problems of the subject is out of key with the general run of cont(-, r,..pora-ry philosophical th-inking. -

Scholars of Islam / Muslims

Scholars of Islam / Muslims Hossein Nasr Hossein Nasr (born April 7, 1933) is an Iranian University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University, USA and a prominent Islamic philosopher. He is the author of many scholarly books and articles. Nasr is a Muslim Persian philosopher and renowned scholar of comparative religion, a lifelong student and follower of Frithj of Schuon, and writes in the fields of Islamic esoterism, Sufism, philosophy of science, and metaphysics. Nasr was the first Muslim to deliver the prestigious Gifford Lectures, and in year 2000, a volume was devoted to him in the Library of Living Philosophers. Professor Nasr speaks and writes based on the doctrine and the viewpoints of the perennial philosophy on subjects such as philosophy, religion, spirituality, music, art, architecture, science, literature, civilization dialogues, and the natural environment. He also wrote two books of poetry (namely Poems of the Way and The Pilgrimage of Life and the Wisdom of Rumi), and has been even described as a 'polymath'. Nasr speaks Persian, English, French, German, Spanish and Arabic fluently. Awards and honors In year 2000, a volume was devoted to him in the Library of Living Philosophers. Templeton Religion and Science Award (1999) First Muslim and first non-Western scholar to deliver the prestigious Gifford Lectures Honorary Doctor of Uppsala University, Sweden (1977) He was nominated and won King Faisal Foundation award, but his prize was withdrawn upon the prize knowledge of his being a Shia. He was notified of winning the prize in 1979 but later the prize was withdrawn with no explanation.