Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Power and the Mediation of Art:The Lasting Impressions of Artistic Intermediality from Seventeenth Century Persia to Present Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2018 Philosophy of Power and the Mediation of Art:The Lasting Impressions of Artistic Intermediality from Seventeenth Century Persia to Present Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic PHILOSOPHY OF POWER AND THE MEDIATION OF ART: THE LASTING IMPRESSIONS OF ARTISTIC INTERMEDIALITY FROM SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PERSIA TO PRESENT Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy May, 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Ali Anooshahr, Ph.D. Professor, Department of History University of California, Davis Committee Member: Christopher Yates, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Philosophy, and Art Theory Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: EL Putnam, Ph.D. Assistant Lecturer, Dublin School of Creative Arts Dublin Institute of Technology ii © 2018 Shadieh Emami Mirmobiny ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii “Do we need a theory of power? Since a theory assumes a prior objectification, it cannot be asserted as a basis for analytical work. But this analytical work cannot proceed without an ongoing conceptualization. And this conceptualization implies critical thought—a constant checking.” — Foucault To my daughter Ariana, and the young generation of students in the Middle East in search of freedom. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to a number of people, without whose assistance and support this dissertation project would not have taken shape and would not have been successfully completed as it was. -

In Search of the Sacred: a Conversation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought

In Search of the Sacred: A Conver- sation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought By Seyyed Hossein Nasr interviewed by Ramin Jahanbegloo Introduction by Terry Moore (Praeger, Santa Barbara, California, USA, 2010) Reviewed by M. Ali Lakhani eyyed Hossein Nasr requires no introduction Sto the readers of this journal. He is one of the foremost living intellectuals, a renowned scholar who has produced (and continues to produce) an impressive corpus of work in fields as diverse as Islamic studies, philosophy, science, history, art, architecture, and the environment, and is arguably the leading representative in the West of the peren- nial philosophy. He has made enormous contribu- tions to Islamic thought, to his own Iranian culture and heritage, and beyond these areas, to a universal humanistic thought rooted in Tradition—and for all of which he has been recognized by being the first non-European (and first Muslim) to deliver the famed Gifford lectures on theology at Edinburgh, the privilege of presenting the Cadbury lectures on the environment, and being only the 28th philosopher inducted by peer-recognition into the prestigious Library of Living Philosophers (along with such predecessors as Einstein, Russell, and Sartre). In fact, the volume on Nasr, published by the Library of Living Philosophers under the title “The Philosophy of Seyyed Hossein Nasr” (2001), contains both an intellectual autobiography of Nasr as well as a series of critical essays and responses, and so covers much of the same territory as the book under review. However, there are several reasons why a reader would also want to read In Search of the Sacred: A Conversation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr on His Life and Thought. -

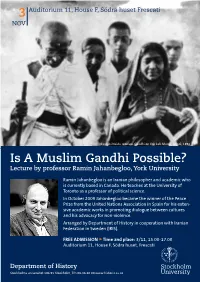

Is a Muslim Gandhi Possible? Lecture by Professor Ramin Jahanbegloo, York University

3 Auditorium 11, House F, Södra huset Frescati NOV Sarojini Naidu receives Gandhi on the Salt March, Dandi, 1930 Is A Muslim Gandhi Possible? Lecture by professor Ramin Jahanbegloo, York University Ramin Jahanbegloo is an Iranian philosopher and academic who is currently based in Canada. He teaches at the University of Toronto as a professor of political science. In October 2009 Jahanbegloo became the winner of the Peace Prize from the United Nations Association in Spain for his exten- sive academic works in promoting dialogue between cultures and his advocacy for non-violence. Arranged by Department of History in cooperation with Iranian Federation in Sweden (IRIS). FREE ADMISSION Time and place: 3/11, 15.00-17.00 Auditorium 11, House F, Södra huset, Frescati Department of History Stockholms universitet 106 91 Stockholm, Tfn 08-16 20 00 www.historia.su.se Is A Muslim Gandhi Possible? Lecture by professor Ramin Jahanbegloo, York University Stockholm University, House F, Auditorium 11 15:00–17:00 Ramin Jahanbegloo, born 1956 in Tehran, is a well-known Iranian-Canadian philosopher. He received his B.A. and M.A. in Philosophy, History and Political Science and later his Ph.D. in Philosophy from the Sorbonne University. In 1993 he taught at the Academy of Philosophy in Tehran. He has been a researcher at the French Institute for Iranian Studies and a fellow at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. Ramin Jahanbegloo taught in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto from 1997-2001. He later served as the head of the Department of Contemporary Studies of the Cultural Research Centre in Tehran and, in 2006-07, was Rajni Kothari Professor of Democracy at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi, India. -

The Influences of Jalal Al-Din Rumi in Seyyed Hossein Nasr’S Sufi Diagnosis of the Environmental Crisis

WHAT WAS SAID TO THE ROSE THAT MADE IT OPEN WAS SAID TO ME, HERE, IN MY CHEST: THE INFLUENCES OF JALAL AL-DIN RUMI IN SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR’S SUFI DIAGNOSIS OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS BY CORY WENSLEY BA, St. Francis Xavier University, 2013 A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theology and Religious Studies January, 2015, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Cory Lee Wensley Approved: Dr. Syed Adnan Hussain Supervisor Approved: Dr. Anne Marie Dalton Examiner Approved: Dr. Linda Darwish Reader Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Genealogical Methodology ........................................................................................................... 10 Chapter One: Literature Review ................................................................................................... 20 Chapter Two: Jalal al-Din Rumi’s Understanding of the Natural Environment and Humanity’s Relationship with It ....................................................................................................................... 53 Chapter Three: Seyyed Hossein Nasr’s Sufi Diagnosis of the Environmental Crisis .................. 82 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. -

"As Long As We Remain Creative and Critical, There Will Be Hope"

"As long as we remain creative and critical, there will be hope" 07/18/2018 The Iranian thinker Ramin Jahanbegloo is a professor of political science at the University of Toronto and a leading expert in the political context of his country and in the philosophy of nonviolence, among other subjects. On July 5, he participated in the dialogue "A troubled world, where does it take us?" along with Rafael Bisquerra, Alfons Cornella, Sara Moreno and Carlota Pi. The event was organized by the Social Council of the UAB as part of the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the university. Many of his books are dialogues with other thinkers such as George Steiner or Isaiah Berlin. What is particular about dialogue as a way of transmitting knowledge? Dialogue has played a very important role in my philosophical thinking. The basis of the dialogue that I have established with people from different cultures has been mainly the Socratic dialogue. Perhaps you do not get definitive answers but aporias, as in the Platonic dialogues; what's really important are the questions. I was a student when I wrote those dialogue books with Steiner and Berlin, and then other shorter ones with Noam Chomsky, Jacques Derrida, Emmanuel Lévinas, Paul Ricoeur ... There were always questions in my mind and I looked for the answer in other people; but you never find the definitive answers because they do not exist. Questioning is the most important thing for humans: without questions, we have no freedom, and without freedom, we have no questions. In an article by him, published in El País , he said that Donald Trump's decision to withdraw from the nuclear agreement with Iran increases the danger of a war. -

Upgrading the Women's Movement in Iran

Upgrading the Women’s Movement in Iran: Through Cultural Activism, Creative Resistance, and Adaptability Meaghan Smead Samuels A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies University of Washington 2018 Committee: Kathie Friedman Sara Curran Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2018 Meaghan Smead Samuels 2 University of Washington Abstract Upgrading the Women’s Movement in Iran: Through Cultural Activism, Creative Resistance, and Adaptability Meaghan Smead Samuels Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kathie Friedman Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies The purpose of this research is to identify and analyze the effects of the 2009 post- election state crackdown on the Iranian Women’s Movement. Varying narratives of how the crackdown affected women’s activism necessitate a better understanding as to how this social movement negotiates periods of repression. An examination of accounts and actions by women in Iran reveal this Movement to be fluid, adaptable, and resilient, utilizing different structures, strategies and tactics depending on the current political environment. This study demonstrates the ability of Iranian women to develop creative solutions for public engagement in repressive moments, including through everyday acts of resistance and by practicing cultural activism. Women in Iran work to transform culture in order to impel the state to make changes to discriminatory laws. Prevailing social movement theories help to explain some characteristics of the Iranian Women’s Movement, but a more complex model is required to account for dynamic gendered social movements in non-Western, authoritarian contexts. -

The Impact of the Modernity Discourse on Persian Fiction

The Impact of the Modernity Discourse on Persian Fiction Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Comparative Studies in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Saeed Honarmand, M.A. Graduate Program in Comparative Studies The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Richard Davis, Advisor Margaret Mills Philip Armstrong Copyright by Saeed Honarmand 2011 Abstract Modern Persian literature has created a number of remarkable works that have had great influence on most middle class people in Iran. Further, it has had representation of individuals in a political context. Coming out of a political and discursive break in the late nineteenth century, modern literature began to adopt European genres, styles and techniques. Avoiding the traditional discourses, then, became one of the primary characteristics of modern Persian literature; as such, it became closely tied to political ideologies. Remarking itself by the political agendas, modern literature in Iran hence became less an artistic source of expression and more as an interpretation of political situations. Moreover, engaging with the political discourse caused the literature to disconnect itself from old discourses, namely Islamism and nationalism, and from people with dissimilar beliefs. Disconnectedness was already part of Iranian culture, politics, discourses and, therefore, literature. However, instead of helping society to create a meta-narrative that would embrace all discourses within one national image, modern literature produced more gaps. Historically, there had been three literary movements before the modernization process began in the late nineteenth century. Each of these movements had its own separate discourse and historiography, failing altogether to provide people ii with one single image of a nation. -

Scholars of Islam / Muslims

Scholars of Islam / Muslims Hossein Nasr Hossein Nasr (born April 7, 1933) is an Iranian University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University, USA and a prominent Islamic philosopher. He is the author of many scholarly books and articles. Nasr is a Muslim Persian philosopher and renowned scholar of comparative religion, a lifelong student and follower of Frithj of Schuon, and writes in the fields of Islamic esoterism, Sufism, philosophy of science, and metaphysics. Nasr was the first Muslim to deliver the prestigious Gifford Lectures, and in year 2000, a volume was devoted to him in the Library of Living Philosophers. Professor Nasr speaks and writes based on the doctrine and the viewpoints of the perennial philosophy on subjects such as philosophy, religion, spirituality, music, art, architecture, science, literature, civilization dialogues, and the natural environment. He also wrote two books of poetry (namely Poems of the Way and The Pilgrimage of Life and the Wisdom of Rumi), and has been even described as a 'polymath'. Nasr speaks Persian, English, French, German, Spanish and Arabic fluently. Awards and honors In year 2000, a volume was devoted to him in the Library of Living Philosophers. Templeton Religion and Science Award (1999) First Muslim and first non-Western scholar to deliver the prestigious Gifford Lectures Honorary Doctor of Uppsala University, Sweden (1977) He was nominated and won King Faisal Foundation award, but his prize was withdrawn upon the prize knowledge of his being a Shia. He was notified of winning the prize in 1979 but later the prize was withdrawn with no explanation. -

Who Instigated the White Revolution of the Shah and the People in Iran, 1963?

Agent or Client: Who Instigated the White Revolution of the Shah and the People in Iran, 1963? A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Michael J. Willcocks School of Arts, Languages and Cultures ! 2! Contents Photographs & Cartoons 5 ! Abstract 6 ! Declaration 7 ! Copyright Statement 8 ! Acknowledgements 9 Introduction 10 Literature Review: US-Iranian Relations and 10 Reform in Iran 1961-63 ! Approach 26 Contribution to Knowledge 28 ! Research Questions 28 ! Hypothesis 28 ! Methodology & Sources 29 ! Thesis Structure 31 ! Transliteration 32 ! ! Chapter 1: Iran! and the United States 1945-61 33 ! 1.1 US-Iranian Relations 1946-61 33 1.2 Iranian Situation 1953-61 39 Chapter 2: ʻAlī Amīnī: The Last Chance? 47 2.1 The Appointment of ʻAlī Amīnī 47 2.1.1 The Man 48 2.1.2 The Controversy 50 2.1.3 Events 52 2.1.4 Explanation 59 2.2 Amīnī’s Plan and Team 66 2.2.1 Amīnī’s Plan 66 2.2.2 Amīnī’s Cabinet 67 2.2.2.1 Ḥasan Arsanjānī 70 2.2.2.2 Nūr al-Dīn Alamūtī 72 2.2.2.3 Muḥammad Dirakhshish 73 2.2.3 A Divided Government 75 2.3 The White House Reacts 77 2.3.1 Economic Assistance 78 ! ! 3! 2.3.1.1 Transition to the Decade of Development 80 2.3.1.2 Reacting to the Crisis in Iran 84 2.3.2 The Iran Task Force 87 2.3.2.1 Policy Objectives 89 2.3.2.2 US Support for Amīnī 93 2.4 Amīnī’s Government: Generating Momentum 97 2.4.1 Anti-Corruption 98 2.4.2 Managing The Economy 100 2.4.3 Third Plan Preparations 101 2.4.4 Land Reform 102 ! Chapter 3: Controlling! the Future 106 ! -

A Guarding of the Change: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Quest for Stability in the Middle East

Liberty University Journal of Statesmanship & Public Policy Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 4 July 2020 A Guarding of the Change: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Quest for Stability in the Middle East Scott Harr Liberty University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jspp Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Harr, Scott (2020) "A Guarding of the Change: Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Quest for Stability in the Middle East," Liberty University Journal of Statesmanship & Public Policy: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/jspp/vol1/iss1/4 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Liberty University Journal of Statesmanship & Public Policy by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harr: A Guarding of the Change 1 Introduction Change is difficult. Civilizations have crumbled and the hopes and dreams of nations have been dashed on the rock of this seemingly incontrovertible truth. The modern Middle East reflects this truth. Despite (or perhaps because of) herculean U.S. investment, the region continues to crush and frustrate U.S. policy objectives in contemporary warfare. Even with the recent rise of Russia and China as the United States’ primary nation state competitors, the Middle East remains vitally important. Great Power competition from Russia and China has only added new layers of threats to a region already featuring dangerous (albeit non-existential) threats to the United States from terrorism, war, and instability. -

The 2009 Presidential Election in Iran: Fair Or Foul? Farhad Khosrokhavar, Marie Ladier-Fouladi

The 2009 Presidential election in Iran: fair or foul? Farhad Khosrokhavar, Marie Ladier-Fouladi To cite this version: Farhad Khosrokhavar, Marie Ladier-Fouladi. The 2009 Presidential election in Iran: fair or foul?. 2021. hal-03209899 HAL Id: hal-03209899 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03209899 Preprint submitted on 27 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2012/29 ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES Mediterranean Programme THE 2009 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN IRAN: FAIR OR FOUL? Farhad Khosrokhavar and Marie Ladier-Fouladi EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES MEDITERRANEAN PROGRAMME The 2009 Presidential election in Iran: fair or foul? FARHAD KHOSROKHAVAR AND MARIE LADIER-FOULADI EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2012/29 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. -

May 8, 2006 Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

May 8, 2006 Ayatollah Ali Khamenei Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran c/o H.E. Javad Zarif Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations Fax: 212-867-7086 Your Excellency: We write to you on behalf of the Committee on Academic Freedom of the Middle East Studies Association of North America (MESA) and the Committee on Academic and Intellectual Freedom of the International Society for Iranian Studies (ISIS) to protest in the strongest possible terms the recent arrest of Dr. Ramin Jahanbegloo, a prominent Iranian intellectual and political theorist. We urge you to use your good offices to determine the circumstances of his detention and to secure his immediate release. The Middle East Studies Association of North America and the International Society for Iranian Studies are the preeminent international organizations in their respective fields. MESA, founded in 1966, and ISIS, founded in 1967, were established to promote scholarship and teaching on Iran, the Middle East, and North Africa. MESA publishes the International Journal of Middle East Studies and has more than 2600 members worldwide; ISIS publishes the international journal of Iranian Studies and has more than 500 members worldwide. Both organizations are committed to ensuring academic freedom, the free exchange of ideas, and freedom of expression in all its forms, both within Iran and the Middle East and in connection with the study of Iran and the Middle East in North America and elsewhere. According to information we have received Dr. Jahanbegloo was arrested at Tehran’s Mehrabad airport in late April.