Walt and the Promise of Progress City'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sleeping Beauty Castle

SLEEPING BEAUTY CASTLE Sheet Numbers: 1 - 18 © Disney Approximate assembly time: 2-3 hours HISTORY INSTRUCTIONS Roof 1 Sheet 4 Inspired by King Ludwig III’s Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, Sheet 3 Sheet 5 (reversed) Sleeping Beauty Castle opened on July 17, 1955, along with Disneyland Sheet 2 Park. Although inspired by the soaring castles of Europe, the Roof 2 Disneyland Castle was proportioned more to the imagination than history. Walt wanted the scale to be warm and welcoming. Although this centerpiece was there when the park opened, guests could not actually walk through the castle’s interior until 1957. Inside, Sheet 1 guests can experience special 3D dioramas and effects that tell the Sleeping Beauty story. We invite you to make your own version of a Sleeping Beauty Castle diorama. Sheets 8 - 13 PART I : THE DIORAMA : Sheets 1 - 13 MATERIALS GUIDE 1. Color all of the pages. 2. Cut out the rectangles on Sheet 1. Please note that these pieces will go from edge to edge on the paper. Use the guidelines to make an accordion fold. 3. Cut out the set pieces on sheets 2, 3, 4, and 5. Ask an adult to help cut out the center portions, as these will serve as windows through the diorama. Glue and fold back the tops and bottoms of the rectangles to keep the pages standing straight! Note that Sets A and B face the front while Set D faces the back. Fold and glue Set C, so it faces both front and back. 4. Cut out the roof pieces on sheets 6 & 7. -

Main Street, U.S.A. • Fantasyland• Frontierland• Adventureland• Tomorrowland• Liberty Square Fantasyland• Continued

L Guest Amenities Restrooms Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Tomorrowland® Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS AED ATTRACTIONS First Aid NEW! Presented by Florida Hospital 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad U 37 Tomorrowland Speedway 26 Enchanted Tales with Belle T AED Guest Relations Information and Lost & Found. AED 27 36 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® Be magically transported from Maurice’s cottage to E Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. ATMs 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ Beast’s library for a delightful storytelling experience. Fantasyland 26 Presented by CHASE AED 28 Package Pickup. Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. AED 27 Under the Sea~Journey of The Little Mermaid AED 34 38 Space Mountain® AAutomatedED External 35 Defibrillators ® Relive the tale of how one Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad 23 S Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite ARunawayED train coaster. lucky little mermaid found true love—and legs! Designated smoking area 39 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s PhilharMagic. 21 32 Baby Care Center 33 40 Tomorrowland Transit Authority AED 28 Ariel’s Grotto Venture into a seaside grotto, Locker rentals 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island 16 PeopleMover Roll through Come explore the Island. where you’ll find Ariel amongst some of her treasures. -

Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom Opens Its Ticketing Gates About an Hour Before Official Park Open

Gaston’s Tavern BARNSTORMER/ Dumbo FASTPASS Be JOURNEY OF Our Pete’s Guest QS/ TS THE LITTLE Silly MERMAID+ Sideshow Enchanted Tales with Walt Disney World Belle+ Railroad Station Ariel’s Haunted it’s a small world+ Pinocchio Mansion+ Village Grotto+ Haus BARNSTORMER+ Regal PETER Carrousel PAN+ DUMBO+ WINNIE Tea BIG THUNDER Columbia THE POOH+ MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Harbor House PRINCESS Party+ Square MAGIC+ MEET+ Walt Disney World Riverboat Railroad Station Tom Sawyer’s Hall of Pooh/ Island Presidents Mermaid FP Indy Sleepy Speedway+ Hollow Cinderella’s Cinderella Cosmic Royal Table Ray’s SPLASH Castle MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Diamond Tree SPACE MOUNTAIN+ H’Shoe Shooting Pecos Country Stitch Auntie Bill Arcade Astro Orbiter Golden Bears Gravity’s Oak Outpost Aloha Isle Tortuga Lunching Pad Tavern Tiki Room Swiss PeopleMover Aladdin’s Family Dessert Monsters Inc. Carpets+ Treehouse Party Laugh Floor+ BUZZ+ JUNGLE Crystal Casey’s Plaza Tomorrowland Pirates of CRUISE+ Palace Corner the Caribbean+ Rest. Terrace Carousel of Main St Progress Bakery SOTMK Tony’s Town Square City Hall MICKEY MOUSE MEET+ Railroad Station t ary Resor emopor Fr ont om Gr Monorail Station To C and Floridian Resor t Resort Bus Stop First Hour Attractions Boat Launch Ferryboat Landing First 2 Hours / Last 2 Hours of Operation Anytime Attractions Table Service Dining Quick Service Dining Shopping Restrooms Attractions labelled in ALL CAPS are FASTPASS enabled. Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom opens its ticketing gates about an hour before official Park open. Guests are held just inside the entrance in the courtyard in front of the train station. The opening show, which features Mickey and the gang arriving via steam train, begins 10 to 15 minutes prior to Park open and lasts about seven minutes. -

Disneyland® Park

There’s magic to be found everywhere at The Happiest Place on Earth! Featuring two amazing Theme Parks—Disneyland® Park and Disney California Adventure® Park—plus three Disneyland® Resort Hotels and the Downtown Disney® District, the world-famous Disneyland® Resort is where Guests of all ages can discover wonder, joy and excitement around every turn. Plan enough days to experience attractions and entertainment in 1 both Parks. 5 INTERSTATE 4 5 2 3 6 Go back and forth between both Theme Parks with a Disneyland® Resort Park Hopper® 1 Disneyland® Hotel 4 Downtown Disney® District Ticket. Plus, when you buy a 3+ day ticket before you arrive, you get one Magic Morning* 2 Disney’s Paradise Pier® Hotel Disneyland® Park early admission to select experiences 5 at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the general public on select days. 3 Disney’s Grand Californian Hotel® & Spa 6 Disney California Adventure® Park *Magic Morning allows one early admission (during the duration of the Theme Park ticket or Southern California CityPASS®) to select attractions, stores, entertainment and dining locations at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the public on Tuesday, Thursday or Saturday. Each member of your travel party must have 3-day or longer Disneyland® Resort tickets. To enhance the Magic Morning experience, it is strongly recommended that Guests arrive at least one hour and 15 minutes prior to regular Park opening. Magic Morning admission is based on availability and does not operate daily. Applicable days and times of operation and all other elements including, but not limited to, operation of attractions, entertainment, stores and restaurants and appearances of Characters may vary and are subject to change without notice. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE How to Grow

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE How to Grow Old: Essays A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts by Andrea Marie Gutierrez June 2012 Thesis Committee: Professor Michael Davis, Chairperson Professor Juan Felipe Herrera Professor Thomas Lutz Copyright by Andrea Marie Gutierrez 2012 The Thesis of Andrea Marie Gutierrez is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my deepest and never-ending gratitude to all of those who have supported me and my work throughout my graduate studies, especially during my second and most difficult year: To the UC Riverside Dean’s and the Distinguished Fellowship Cheech Marin Endowment Scholarship administered by the Hispanic Scholarship Fund, for providing funding towards my studies. To Susan Straight, who was there when no one else was; Goldberry Long, for your tremendously helpful insights about revision; Juan Felipe Herrera, for banishing my gremlins; Tom Lutz, for your empathy and humor; Chris Abani, for the first call that brought me to Riverside and the humanity that you bring to your teaching; Mike Davis, for everything. These two years at UCR would have been unlivable without the friendship and camaraderie of my fellow writers: Kris Ide, Angel García, David Campos, and Sara Borjas. Marc, for making sure I got my grad school applications in on time. Rachelle Cruz, I could not have made it this far without you and your generosity. You have been a beacon in my night. Jill, Ed, and Casey, for being my besties through the thinnest of years. -

Holidays at the Disneyland® Resort Is the Most

® MAKING THE MOST OF YOUR PASSHOLDER MEMBERSHIP q WINTER 2008 HOLIDAYS AT THE DISNEYLAND® RESORT IS THE MOST WONDERFUL TIME OF THE YEAR ALSO INSIDE: What Will You Celebrate?, Imagineering Secrets, Holiday Shopping, and More! ] HOLIDAY I FEATURE STORY DAZZLE. RESORT SPOTLIGHT RESORT I DISNEY STYLE Snowflakes, icicles and twinkling lights add sparkle to the season! . For some people—especially many Annual from Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas.* Passholders—it just isn’t the holidays until they’ve made Now, if you really want to boost your holiday cheer INSIDER INFO I that first visit of the season to the Disneyland ® Resort. level, you’ve got to take a cruise on “it’s a small world” There’s something extra-magical about stepping out onto holiday. The classic attraction is making its eagerly awaited Main Street, U.S.A., seeing the towering tree with all of return just in time to celebrate the holidays. Once more, its colorful decorations, and hearing the strains of holiday children from around the globe will welcome Guests music filling the air. It dazzles the senses and warms the with their special holiday version of the attraction’s soul at the same time. And everywhere you go, there’s an famous theme song. If that doesn’t kick-start your added layer of enchantment—including special seasonal spirit, then the thousands of twinkling lights adorning touches to some of your favorite attractions. Even the the refreshed façade will most certainly do the trick! Haunted Mansion takes on a happy holiday glow this Speaking of impressive light displays, be sure to time of year—courtesy of Jack Skellington and his friends catch a performance of Disney’s Electrical Parade over in Disney’s California Adventure ® Park on select days. -

Trams Der Welt / Trams of the World 2020 Daten / Data © 2020 Peter Sohns Seite/Page 1 Algeria

www.blickpunktstrab.net – Trams der Welt / Trams of the World 2020 Daten / Data © 2020 Peter Sohns Seite/Page 1 Algeria … Alger (Algier) … Metro … 1435 mm Algeria … Alger (Algier) … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Constantine … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Oran … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Ouragla … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Sétif … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Algeria … Sidi Bel Abbès … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF … Metro … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Caballito … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Lacroze (General Urquiza) … Interurban (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Premetro E … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Buenos Aires, DF - Tren de la Costa … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Córdoba, Córdoba … Trolleybus … Argentina … Mar del Plata, BA … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 900 mm Argentina … Mendoza, Mendoza … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Mendoza, Mendoza … Trolleybus … Argentina … Rosario, Santa Fé … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Argentina … Rosario, Santa Fé … Trolleybus … Argentina … Valle Hermoso, Córdoba … Tram-Museum (Electric) … 600 mm Armenia … Yerevan … Metro … 1524 mm Armenia … Yerevan … Trolleybus … Australia … Adelaide, SA - Glenelg … Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Australia … Ballarat, VIC … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm Australia … Bendigo, VIC … Heritage-Tram (Electric) … 1435 mm www.blickpunktstrab.net – Trams der Welt / Trams of the World 2020 Daten / Data © 2020 Peter Sohns Seite/Page -

The Craig Krull Collection the Craig Krull Collection

Disneyland COVER THE CRAIG KRULL COLLECTION THE CRAIG KRULL COLLECTION FRIDAY JUNE 9, 2017 IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING LOT 611 OF ANIMATION & DISNEYANA AUCTION 94 LIVE • MAIL • PHONE • FAX • INTERNET Place your bid over the Internet! PROFILES IN HISTORY will be providing Internet-based bidding to qualified bidders in real-time on the day of the auction. For more information visit us @ www.profilesinhistory.com CATALOG PRICE AUCTION LOCATION (PREVIEWS BY APPOINTMENT ONLY) $35.00 PROFILES IN HISTORY, 26662 AGOURA ROAD, CALABASAS, CA 91302 CALL: 310-859-7701 FAX: 310-859-3842 This auction is a continuation of Profiles in History’s Animation & Disneyana Auction 94, which begins at 11 am PDT on June 9th, 2017, and will commence immediately following Lot 611 of Auction 94. Bidders may register by phone, online at www.profilesinhistory.com, or use the registration and bidding forms in the Auction 94 catalog. “CONDITIONS OF SALE” Profiles may accept current and valid VISA, MasterCard, Discover removed from the premises or possession transferred to Buyer unless and American Express credit or debit cards for payment but under Buyer has fully complied with these Conditions of Sale and the terms AGREEMENT BETWEEN PROFILES IN HISTORY AND the express condition that any property purchased by credit or debit of the Registration Form, and unless and until Profiles has received BIDDER. BY EITHER REGISTERING TO BID OR PLACING A card shall not be refundable, returnable, or exchangeable, and that no the Purchase Price funds in full. Notwithstanding the above, all BID, THE BIDDER ACCEPTS THESE CONDITIONS OF SALE credit to Buyer’s credit or debit card account will be issued under any property must be removed from the premises by Buyer at his or her AND ENTERS INTO A LEGALLY, BINDING, ENFORCEABLE circumstances. -

Seasonal Meet & Greets, Holiday Ride Experiences

A Jolly Guide to Mickey's Very Merry Christmas Party Seasonal Meet & Greets, Holiday Ride Experiences and Complimentary Sweet Surprises H O L L Y J O L L Y E X P E R I E N C E S What's Character Meet & Greet Locations Included in Holiday Ride Experiences Complimentary Sweet Treats this Guide? Guru Travel, LLC |Winter 2019 O R G A N I Z E D B Y L O C A T I O N SEASONAL CHARACTER MEET & GREETS G U R U T R A V E L Adventureland M O A N A T H E E N C H A N T E D T I K I R O O M C A P T A I N J A C K S P A R R O W P I R A T E S O F T H E C A R I B B E A N , O N L Y D U R I N G T H E D A Y A L A D D I N & A B U A G R A B A H B A Z A A R J A S M I N E & G E N I E A G R A B A H B A Z A A R P E T E R P A N R O A M I N G T H R O U G H O U T A D V E N T U R E L A N D F R O N T I E R L A N D Big Al, Liverlips, Shaker and Wendell (Country Bears) Near Country Bear Jamboree Fantasyland D O N A L D & S C R O O G E M C D U C K Storybook Circus, near Casey Jr. -

2020 Fastpass Guide to Understanding Tiers by Life Is Better Traveling

2020 FastPass Guide to Understanding Tiers by Life is Better Traveling MAGIC KINGDOM® PICK THREE • Mickey's PhilharMagic • Big Thunder Mountain Railroad • Astro Orbiter • Peter Pan's Flight • Country Bear Jamboree • Buzz Lightyear's Space Ranger Spin • Prince Charming Regal Carrousel • Splash Mountain • Monsters, Inc. Laugh Floor • Seven Dwarfs Mine Train • Frontierland Shootin' Arcade • Space Mountain • The Barnstormer featuring the Great • Tom Sawyer Island • Stitch's Great Escape! Goofini • Walt Disney World Railroad • Tomorrowland Speedway • The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh • Mad Tea Party • Tomorrowland Transit Authority • Under the Sea: Journey of the Little Meet and Greets FastPass PeopleMover Mermaid • *Meet Ariel at Her Grotto • Walt Disney's Carousel of Progress • Walt Disney World Railroad • *Meet Cinderella and Elena at • Dumbo the Flying Elephant • The Hall of Presidents Princess Fairytale Hall • Enchanted Tales with Belle • The Haunted Mansion • *Meet Mickey Mouse at Town Square Theater • It's a Small World • Liberty Square Riverboat • *Meet Repunzel and Tiana at • Big Thunder Mountain Railroad • Splash Mountain Princess Fairytale Hall • Country Bear Jamboree • Frontierland Shootin' Arcade • *Meet TinkerBell at Town Square • Tom Sawyer Island • Walt Disney World Railroad Theatre EPCOT® TIER ONE (Pick 1) TIER TWO (Pick 2) • Frozen Ever After • Figment: Journey Into • Living with the Land • Soarin’ Around the World Imagination • Turtle Talk with Crush • Test Track • Mission: SPACE • Spaceship Earth • Epcot Forever • -

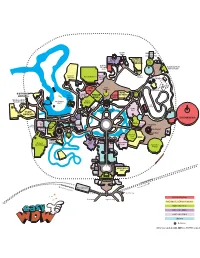

DL Map-Disneyland Resort.Pdf

There’s more to see and do at the Disneyland® Resort than ever before! Surround yourself in the magic of two Disney Parks– including the re-imagined Disney California Adventure® Park and the one-and-only original Disneyland® Park! Stay right in the middle of the action at one of the three incredible resort Hotels and discover entertainment, dining and shopping in the Downtown Disney® District. With more than 100 shows and attractions plus all the excitement outside the Parks, you and your family will need a few 1 days to experience it all. 5 INTERSTATE 4 5 2 3 RIVE D D 6 D DISNE YLAN ©Disney/Pixar K OULEVAR ATELLA B A VE NUE ARB OR H 1 Disneyland® Hotel 4 Downtown Disney® District 2 Disney Paradise Pier® Hotel 5 Disneyland® Park 3 Disney Grand Californian Hotel® & Spa 6 Disney California Adventure® Park GPS2012-7675-1 ©Disney 6177 21 22 MICkey’s TOONTOWN 20 23 24 CARS LAND 25 26 MAIN STREET, U.S.A. MICKEy’S toontown 25 23 24 26 PARADISE PIER 27 1 Disneyland® Railroad 20 Gadget’s Go Coaster presented by Sparkle®. 19 38 34 27 20 2 The Disney Gallery (Minimum height 35”/89 cm) 37 19 39 32 31 3 The Disneyland® Story 21 Mickey’s House and 35 33 28 33 28 presenting Great Moments 40 36 30 “a bug’s land” PACIFIC WHARF Meet Mickey 31 12 18 FANTASYLAND 30 with Mr. Lincoln 13 41 15 21 32 22 Minnie’s House CRITTER COUNTRY 17 43 44 29 ADVENTURELAND FRONTIERLAND 18 11 29 16 17 23 Roger Rabbit’s Car 42 63 45 RIVERS OF 16 15 2 3 46 22 4 Enchanted Tiki Room 4 53 8 13 presented by Dole® (Continuous shows) Toon Spin AMERICA 14 5 11 14 12 13 52 TOMORROWLAND -

Disneyland Resort

There’s more to see and do at the Disneyland® Resort than ever before! Surround yourself in the magic of two Disney Parks– including the re-imagined Disney California Adventure® Park and the one-and-only original Disneyland® Park! Stay right in the middle of the action at one of the three incredible resort Hotels and discover entertainment, dining and shopping in the Downtown Disney® District. With more than 100 shows and attractions plus all the excitement outside the Parks, you and your family will need a few 1 days to experience it all. 5 INTERSTATE 4 5 2 3 RIVE D D 6 D DISNE YLAN ©Disney/Pixar K OULEVAR ATELLA B A VE NUE ARB OR H 1 Disneyland® Hotel 4 Downtown Disney® District 2 Disney Paradise Pier® Hotel 5 Disneyland® Park 3 Disney Grand Californian Hotel® & Spa 6 Disney California Adventure® Park GPS2012-7675-1 ©Disney 6177 21 22 MICkey’s TOONTOWN 20 23 24 CARS LAND 25 26 MAIN STREET, U.S.A. MICKEy’S toontown 25 23 24 26 PARADISE PIER 27 1 Disneyland® Railroad 20 Gadget’s Go Coaster presented by Sparkle®. 19 38 34 27 20 2 The Disney Gallery (Minimum height 35”/89 cm) 37 19 39 32 31 3 The Disneyland® Story 21 Mickey’s House and 35 33 28 33 28 presenting Great Moments 40 36 30 “a bug’s land” PACIFIC WHARF Meet Mickey 31 12 18 FANTASYLAND 30 with Mr. Lincoln 13 41 15 21 32 22 Minnie’s House CRITTER COUNTRY 17 43 44 29 ADVENTURELAND FRONTIERLAND 18 11 29 16 17 23 Roger Rabbit’s Car 42 63 45 RIVERS OF 16 15 2 3 46 22 4 Enchanted Tiki Room 4 53 8 13 presented by Dole® (Continuous shows) Toon Spin AMERICA 14 5 11 14 12 13 52 TOMORROWLAND