Florida Freight Rail Needs Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.0 Current Freight Rail System and Services in Florida

Investment Element of the 2010 Florida Rail System Plan 2.0 Current Freight Rail System and Services in Florida 2.1 Overview The Florida rail system is comprised of 2,786 miles of mainline track, which are owned by 15 operating line-haul railroads and terminal or switching companies, as well as 81 miles owned by the State of Florida. Florida’s rail system includes 2 Class I Railroads (CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Corporation), 1 Class II (Florida East Coast Railway), 11 Class III (Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway AN Railway, Bay Line Railroad, First Coast Railroad, Florida West Coast Railroad, Florida Central Railroad, Florida Midland Railroad, Florida Northern Railroad, Georgia and Florida Railway, Seminole Gulf Railway, and South Central Florida Express) and 1 railroad specializing in switching and terminals (Talleyrand Terminal).9 The largest operator in the State is CSX Transportation, which owns more than 53 percent of the statewide track mileage. In 2008, Florida’s railroads carried nearly 1.6 million carloads – 19 percent less than in 2006 – and approximately 83 million tons of freight, representing a 25 million ton (23 percent) decrease from 2006.10 During that year, railroads handled freight equivalent to roughly 5.0 million heavy trucks.11 Nonetheless, railroads continue to support thousands of jobs throughout the State and assist Florida’s industries to remain competitive with international and domestic markets for fertilizer, construction rock, consumer goods, paper products, processed 9 U.S. Class I Railroads are line-haul freight railroads with 2007 operating revenue in excess of $359.6 million (2006 operating revenues exceeding $346.7 million). -

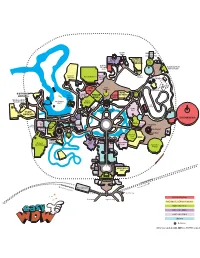

Main Street, U.S.A. • Fantasyland• Frontierland• Adventureland• Tomorrowland• Liberty Square Fantasyland• Continued

L Guest Amenities Restrooms Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Tomorrowland® Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS AED ATTRACTIONS First Aid NEW! Presented by Florida Hospital 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad U 37 Tomorrowland Speedway 26 Enchanted Tales with Belle T AED Guest Relations Information and Lost & Found. AED 27 36 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® Be magically transported from Maurice’s cottage to E Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. ATMs 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ Beast’s library for a delightful storytelling experience. Fantasyland 26 Presented by CHASE AED 28 Package Pickup. Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. AED 27 Under the Sea~Journey of The Little Mermaid AED 34 38 Space Mountain® AAutomatedED External 35 Defibrillators ® Relive the tale of how one Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad 23 S Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite ARunawayED train coaster. lucky little mermaid found true love—and legs! Designated smoking area 39 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s PhilharMagic. 21 32 Baby Care Center 33 40 Tomorrowland Transit Authority AED 28 Ariel’s Grotto Venture into a seaside grotto, Locker rentals 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island 16 PeopleMover Roll through Come explore the Island. where you’ll find Ariel amongst some of her treasures. -

The Signal Bridge

THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Volume 18 NEWSLETTER OF THE MOUNTAIN EMPIRE MODEL RAILROADERS CLUB Number 5B MAY 2011 BONUS PAGES Published for the Education and Information of Its Membership NORFOLK & WESTERN/SOUTHERN RAILWAY DEPOT BRISTOL TENNESSEE/VIRGINIA CLUB OFFICERS LOCATION HOURS President: Secretary: Newsletter Editor: ETSU Campus, Business Meetings are held the Fred Alsop Donald Ramey Ted Bleck-Doran: George L. Carter 3rd Tuesday of each month. Railroad Museum Meetings start at 7:00 PM at Vice-President: Treasurer: Webmaster: ETSU Campus, Johnson City, TN. John Carter Duane Swank John Edwards Brown Hall Science Bldg, Room 312, Open House for viewing every Saturday from 10:00 am until 3:00 pm. Work Nights each Thursday from 5:00 pm until ?? APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Page 2 APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE Page 3 APRIL 2011 THE SIGNAL BRIDGE II scheme. The "stripe" style paint schemes would be used on AMTRAK PAINT SCHEMES Amtrak for many more years. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Phase II Amtrak paint schemes or "Phases" (referred to by Amtrak), are a series of livery applied to the outside of their rolling stock in the United States. The livery phases appeared as different designs, with a majority using a red, white, and blue (the colors of the American flag) format, except for promotional trains, state partnership routes, and the Acela "splotches" phase. The first Amtrak Phases started to emerge around 1972, shortly after Amtrak's formation. Phase paint schemes Phase I F40PH in Phase II Livery Phase II was one of the first paint schemes of Amtrak to use entirely the "stripe" style. -

UTU News. June2008

Volume 4 0 June 2008 N u m b e r 6 www.utuia.org www.utu.org The Official Publication of the United Transportation Union News and Notes U.S. rail members ratify Accidents take members Three UTU members – Eli A. Locklear, James Wilson, and David C. Goolsby – have U T U national agre e m e n t been killed in separate incidents. By overwhelming margins within each craft, “ A d d i t i o n a l l y,” said Futhey, “the UTU was L o c k l e a r, 46, a CSX conductor and member of Local 1011 at Hamlet, N.C., was killed May members of the United Transportation Union the only union to gain continuation of a COLA, 26 when he was crushed by tons of coal while have ratified a new national rail agreement beginning in 2010, while a new agreement is unloading a train. He was part of a two-person covering wages, rules and being negotiated. The COLA put crew that was unloading a 97-car train at working conditions. some $7 more per day in members’ Progress Energ y ’s Weatherspoon Plant when he The ratified agreement is pockets while we were at the nego- either fell or was pulled down into the coal. retroactive to Jan. 1, 2005, tiating table this round. Wilson, 35, a UP conductor and member and remains in force through “ We also retained, undis- of Local 923 in Dalhart, Texas, was riding on Dec. 31, 2009. turbed, our locally negotiat- top of a train car that was being pushed in an Amarillo, Texas, yard when he fell and was “In the face of recurring ed crew-consist agreements, hit by the train. -

US Army Railroad Course Railway Track Maintenance II TR0671

SUBCOURSE EDITION TR0671 1 RAILWAY TRACK MAINTENANCE II Reference Text (RT) 671 is the second of two texts on railway track maintenance. The first, RT 670, Railway Track Maintenance I, covers fundamentals of railway engineering; roadbed, ballast, and drainage; and track elements--rail, crossties, track fastenings, and rail joints. Reference Text 671 amplifies many of those subjects and also discusses such topics as turnouts, curves, grade crossings, seasonal maintenance, and maintenance-of-way management. If the student has had no practical experience with railway maintenance, it is advisable that RT 670 be studied before this text. In doing so, many of the points stressed in this text will be clarified. In addition, frequent references are made in this text to material in RT 670 so that certain definitions, procedures, etc., may be reviewed if needed. i THIS PAGE WAS INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK. ii CONTENTS Paragraph Page INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1. TRACK REHABILITATION............................................................. 1.1 7 Section I. Surfacing..................................................................................... 1.2 8 II. Re-Laying Rail............................................................................ 1.12 18 III. Tie Renewal................................................................................ 1.18 23 CHAPTER 2. TURNOUTS AND SPECIAL SWITCHES........................................................................................ -

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report Genesee & Wyoming Inc.*owns or leases 122 freight railroads worldwide that are organized into 10 operating regions with approximately 7,300 employees and 3,000 customers. * The terms “Genesee & Wyoming,” “G&W,” “the company,” “we,” “our,” and “us” refer collectively to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. and its subsidiaries and affiliated companies. Financial Highlights Years Ended December 31 (In thousands, except per share amounts) 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Statement of Operations Data Operating revenues $874,916 $1,568,643 $1,639,012 $2,000,401 $2,001,527 Operating income 190,322 380,188 421,571 384,261 289,612 Net income 52,433 271,296 261,006 225,037 141,096 Net income attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 48,058 269,157 260,755 225,037 141,137 Diluted earnings per common share attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. common stockholders: Diluted earnings per common share (EPS) $1.02 $4.79 $4.58 $3.89 $2.42 Weighted average shares - Diluted 51,316 56,679 56,972 57,848 58,256 Balance Sheet Data as of Period End Total assets $5,226,115 $5,319,821 $5,595,753 $6,703,082 $7,634,958 Total debt 1,858,135 1,624,712 1,615,449 2,281,751 2,359,453 Total equity 1,500,462 2,149,070 2,357,980 2,519,461 3,187,121 Operating Revenues Operating Income Net Income Diluted Earnings ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) 421.61,2 Per Common Share 2 2,001.5 401.6 1 $2,000 2,000.4 $400 394.12 $275 271.3 $5.00 1 2 4.79 1 374.3 1 380.21 384.3 261.0 4.581 1,800 250 4.50 350 1,639.0 225.01 225 2 1 1,600 233.5 4.00 2 3.89 1,568.6 4.10 2 300 2 200 213.9 213.3 2 3.78 2 1,400 1 3.50 3.69 289.6 183.32 3.142 250 175 1,200 3.00 211. -

CS/HB 489 Railroad Police Officers SPONSOR(S): Criminal Justice Subcommittee; Stone and Others TIED BILLS: IDEN./SIM

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STAFF ANALYSIS BILL #: CS/HB 489 Railroad Police Officers SPONSOR(S): Criminal Justice Subcommittee; Stone and others TIED BILLS: IDEN./SIM. BILLS: REFERENCE ACTION ANALYST STAFF DIRECTOR or BUDGET/POLICY CHIEF 1) Criminal Justice Subcommittee 11 Y, 0 N, As Cunningham Cunningham CS 2) Justice Appropriations Subcommittee 13 Y, 0 N McAuliffe Jones Darity 3) Judiciary Committee SUMMARY ANALYSIS The Criminal Justice Standards and Training Commission (CJSTC) establishes uniform minimum standards for the employment and training of law enforcement officers (LEOs). Currently, CJSTC certifies a person for employment as an LEO if: The person complies with s. 943.13(1)-(10), F.S.; and The employing agency complies with s. 943.133(2) and (3), F.S. Section 943.10, F.S., defines the term “law enforcement officer” to include only those elected, appointed, or employed full time by any municipality, the state, or any political subdivision of the state. Similarly, the definition of the term “employing agency” only includes agencies or units of government, municipalities, the state, or any political subdivision of the state that has the authority to employ officers. Section 354.01, F.S., authorizes the Governor to appoint “special officers,” which are persons employed by railroads for the protection of the railroad’s employees, passengers, freight, equipment, and properties. Special officers are required to meet the law enforcement qualifications and training requirements of s. 943.13(1)-(10), F.S., but they are not certified law enforcement officers because they do not work for an “employing agency.” Railroads and common carriers that employ special officers are not considered employing agencies because they are not governmental entities. -

The FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Volume XXXII October, 1953 Number 2 The FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY CONTENTS The Florida, Atlantic and Gulf Central Railroad Paul E. Fenlon The Election of 1876 in Florida Gov. Marcellus L. Stearns (ed. by) Edward C. Williamson Spanish Interest in British Florida Mark F. Boyd & Jose N. Latorre Book Reviews: Pettingill, “Story of the Florida Railroads” Dorothy Dodd Graff, “Mandarin on the St. Johns” Dena Snodgrass Sitterson, “Sugar Country” J. E. Dovell Wilgus (ed.) “The Caribbean” Ione S. Wright Aguilera (ed.) “Handbook of Latin American Studies” Marshall K. Powers Newman, “Indian River History” Southern Historical Association in Jacksonville Historical Association of Southern Florida The Florida Historical Society New members SUBSCRIPTION FOUR DOLLARS SINGLE COPIES ONE DOLLAR (Copyright, 1953, by the Florida Historical Society. Reentered as second class matter November 21, 1947, at the post office at Tallahassee, Florida, under the Act of August 24, 1912.) Office of publication, Tallahassee, Florida Published quarterly by THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Gainesville, Florida THE FLORIDA, ATLANTIC AND GULF CENTRAL R. R. THE FIRST RAILROAD IN JACKSONVILLE by PAUL E. FENLON Though the factors responsible for the failure of Florida to ex- perience the rapid economic development which took place in the vast western areas of the United States during the latter half of the nineteenth century are numerous and diverse, lack of ade- quate railroad transportation, certainly until the 1880’s, stands out as one of the most important. Midway in the nineteenth century there was not in operation a single mile of railroad in the entire State of Florida. 1 Further- more, the development of railroad transportation facilities that did take place during most of the remainder of the century was spo- radic and relatively unplanned. -

2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan

final report 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan prepared for Florida Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Charles River Associates June 2005 final report 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan prepared for Florida Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 4445 Willard Avenue, Suite 300 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 with Charles River Associates Inc. June 2005 2004 Freight Rail Component of the Florida Rail Plan Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. ES-1 Purpose........................................................................................................................... ES-1 Florida’s Rail System.................................................................................................... ES-2 Freight Rail and the Florida Economy ....................................................................... ES-7 Trends and Issues.......................................................................................................... ES-15 Future Rail Investment Needs .................................................................................... ES-17 Strategies and Funding Opportunities ...................................................................... ES-19 Recommendations........................................................................................................ -

Nurail Project ID: Nurail2012-UTK-R04 Macro Scale

NURail project ID: NURail2012-UTK-R04 Macro Scale Models for Freight Railroad Terminals By Mingzhou Jin Professor Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering University of Tennessee at Knoxville E-mail: [email protected] David B. Clarke Director of the Center for Transportation Research University of Tennessee at Knoxville E-mail: [email protected] Grant Number: DTRT12-G-UTC18 March 2, 2016 Page 1 of 6 DISCLAIMER Funding for this research was provided by the NURail Center, University of Illinois at Urbana - Champaign under Grant No. DTRT12-G-UTC18 of the U.S. Department of Transportation, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research & Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Centers Program. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program, in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. March 2, 2016 Page 2 of 6 TECHNICAL SUMMARY Title Macro Scale Models for Freight Railroad Terminals Introduction This project has developed a yard capacity model for macro-level analysis. The study considers the detailed sequence and scheduling in classification yards and their impacts on yard capacities simulate typical freight railroad terminals, and statistically analyses of the historical and simulated data regarding dwell-time and traffic flows. Approach and Methodology The team developed optimization models to investigate three sequencing decisions are at the areas inspection, hump, and assembly. -

Sounder Commuter Rail (Seattle)

Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Final Report PRC 14-12 F Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Texas A&M Transportation Institute PRC 14-12 F December 2014 Authors Jolanda Prozzi Rydell Walthall Megan Kenney Jeff Warner Curtis Morgan Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 8 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 9 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 10 Sharing Rail Infrastructure ........................................................................................................ 10 Three Scenarios for Sharing Rail Infrastructure ................................................................... 10 Shared-Use Agreement Components .................................................................................... 12 Freight Railroad Company Perspectives ............................................................................... 12 Keys to Negotiating Successful Shared-Use Agreements .................................................... 13 Rail Infrastructure Relocation ................................................................................................... 15 Benefits of Infrastructure Relocation ................................................................................... -

Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom Opens Its Ticketing Gates About an Hour Before Official Park Open

Gaston’s Tavern BARNSTORMER/ Dumbo FASTPASS Be JOURNEY OF Our Pete’s Guest QS/ TS THE LITTLE Silly MERMAID+ Sideshow Enchanted Tales with Walt Disney World Belle+ Railroad Station Ariel’s Haunted it’s a small world+ Pinocchio Mansion+ Village Grotto+ Haus BARNSTORMER+ Regal PETER Carrousel PAN+ DUMBO+ WINNIE Tea BIG THUNDER Columbia THE POOH+ MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Harbor House PRINCESS Party+ Square MAGIC+ MEET+ Walt Disney World Riverboat Railroad Station Tom Sawyer’s Hall of Pooh/ Island Presidents Mermaid FP Indy Sleepy Speedway+ Hollow Cinderella’s Cinderella Cosmic Royal Table Ray’s SPLASH Castle MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Diamond Tree SPACE MOUNTAIN+ H’Shoe Shooting Pecos Country Stitch Auntie Bill Arcade Astro Orbiter Golden Bears Gravity’s Oak Outpost Aloha Isle Tortuga Lunching Pad Tavern Tiki Room Swiss PeopleMover Aladdin’s Family Dessert Monsters Inc. Carpets+ Treehouse Party Laugh Floor+ BUZZ+ JUNGLE Crystal Casey’s Plaza Tomorrowland Pirates of CRUISE+ Palace Corner the Caribbean+ Rest. Terrace Carousel of Main St Progress Bakery SOTMK Tony’s Town Square City Hall MICKEY MOUSE MEET+ Railroad Station t ary Resor emopor Fr ont om Gr Monorail Station To C and Floridian Resor t Resort Bus Stop First Hour Attractions Boat Launch Ferryboat Landing First 2 Hours / Last 2 Hours of Operation Anytime Attractions Table Service Dining Quick Service Dining Shopping Restrooms Attractions labelled in ALL CAPS are FASTPASS enabled. Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom opens its ticketing gates about an hour before official Park open. Guests are held just inside the entrance in the courtyard in front of the train station. The opening show, which features Mickey and the gang arriving via steam train, begins 10 to 15 minutes prior to Park open and lasts about seven minutes.