History According to Disney a Comparative Analysis of the Historical Theming in Disneyland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Sleeping Beauty Castle

SLEEPING BEAUTY CASTLE Sheet Numbers: 1 - 18 © Disney Approximate assembly time: 2-3 hours HISTORY INSTRUCTIONS Roof 1 Sheet 4 Inspired by King Ludwig III’s Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, Sheet 3 Sheet 5 (reversed) Sleeping Beauty Castle opened on July 17, 1955, along with Disneyland Sheet 2 Park. Although inspired by the soaring castles of Europe, the Roof 2 Disneyland Castle was proportioned more to the imagination than history. Walt wanted the scale to be warm and welcoming. Although this centerpiece was there when the park opened, guests could not actually walk through the castle’s interior until 1957. Inside, Sheet 1 guests can experience special 3D dioramas and effects that tell the Sleeping Beauty story. We invite you to make your own version of a Sleeping Beauty Castle diorama. Sheets 8 - 13 PART I : THE DIORAMA : Sheets 1 - 13 MATERIALS GUIDE 1. Color all of the pages. 2. Cut out the rectangles on Sheet 1. Please note that these pieces will go from edge to edge on the paper. Use the guidelines to make an accordion fold. 3. Cut out the set pieces on sheets 2, 3, 4, and 5. Ask an adult to help cut out the center portions, as these will serve as windows through the diorama. Glue and fold back the tops and bottoms of the rectangles to keep the pages standing straight! Note that Sets A and B face the front while Set D faces the back. Fold and glue Set C, so it faces both front and back. 4. Cut out the roof pieces on sheets 6 & 7. -

Main Street, U.S.A. • Fantasyland• Frontierland• Adventureland• Tomorrowland• Liberty Square Fantasyland• Continued

L Guest Amenities Restrooms Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Tomorrowland® Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS AED ATTRACTIONS First Aid NEW! Presented by Florida Hospital 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad U 37 Tomorrowland Speedway 26 Enchanted Tales with Belle T AED Guest Relations Information and Lost & Found. AED 27 36 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® Be magically transported from Maurice’s cottage to E Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. ATMs 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ Beast’s library for a delightful storytelling experience. Fantasyland 26 Presented by CHASE AED 28 Package Pickup. Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. AED 27 Under the Sea~Journey of The Little Mermaid AED 34 38 Space Mountain® AAutomatedED External 35 Defibrillators ® Relive the tale of how one Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad 23 S Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite ARunawayED train coaster. lucky little mermaid found true love—and legs! Designated smoking area 39 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s PhilharMagic. 21 32 Baby Care Center 33 40 Tomorrowland Transit Authority AED 28 Ariel’s Grotto Venture into a seaside grotto, Locker rentals 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island 16 PeopleMover Roll through Come explore the Island. where you’ll find Ariel amongst some of her treasures. -

Disneyland Paris Review by Joan Finder

Disneyland Paris Review By Joan Finder It’s a Magical Morning and I am walking down Main Street USA! Yes, there is City Hall and the Emporium, but why does the hat shop say Chapeaux? Oh well, straight ahead, there it is…. The castle! But somehow it seems a brighter pink and a bit taller. And now the counter service cast member is handing me…. a croque monsieur and café au lait? This IS Disneyland, isn’t it? Yes, it must be—because there he is: Mickey Mouse himself with his wide grin, saying … “Bon Jour”?!? Is this a dream? No, it’s a dream-come-true! I am an American in Paris—Disneyland Paris! I never thought it was possible that a park could be even more beautiful than Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World, or Walt’s original Disneyland CA, but Disneyland Paris achieves it. The details and the colors are just breathtaking, especially the pinks and blues reminiscent of the Impressionist Art for which Paris is known. Walking up MainStreet USA, which feels comfortingly familiar and yet teasingly strange at the same time, the castle doesn't appear much different than the Walt Disney World castle, until you walk around to the side and see the huge hill, boxed trees, waterfalls and lawns leading up to it. Plus, it even has a sleeping dragon in the cave below who wakes and breathes smoke! And if you go up the stairs, you can read the story of La Belle Au Bois Dormant , in French, of course, or just follow the tale of the Sleeping Beauty through a series of shining stained glass windows and elegant tapestries. -

The Immersive Theme Park

THE IMMERSIVE THEME PARK Analyzing the Immersive World of the Magic Kingdom Theme Park JOOST TER BEEK (S4155491) MASTERTHESIS CREATIVE INDUSTRIES Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor: C.C.J. van Eecke 22 July 2018 Summary The aim of this graduation thesis The Immersive Theme Park: Analyzing the Immersive World of the Magic Kingdom Theme Park is to try and understand how the Magic Kingdom theme park works in an immersive sense, using theories and concepts by Lukas (2013) on the immersive world and Ndalianis (2004) on neo-baroque aesthetics as its theoretical framework. While theme parks are a growing sector in the creative industries landscape (as attendance numbers seem to be growing and growing (TEA, 2016)), research on these parks seems to stay underdeveloped in contrast to the somewhat more accepted forms of art, and almost no attention was given to them during the writer’s Master’s courses, making it seem an interesting choice to delve deeper into this subject. Trying to reveal some of the core reasons of why the Disney theme parks are the most visited theme parks in the world, and especially, what makes them so immersive, a profound analysis of the structure, strategies, and design of the Magic Kingdom theme park using concepts associated with the neo-baroque, the immersive world and the theme park is presented through this thesis, written from the perspective of a creative master student who has visited these theme parks frequently over the past few years, using further literature, research, and critical thinking on the subject by others to underly his arguments. -

Downtown Disney District: Fact Sheet

Downtown Disney District: Fact Sheet ANAHEIM, Calif. – (July 8, 2020) The Downtown Disney District at the Disneyland Resort is a one-of-a-kind Disney experience, immersing guests in an exciting mix of family-friendly dining and shopping in a vibrant setting. A phased reopening of this outdoor promenade begins July 9, 2020. The 20-acre, 300,000 square-foot Downtown Disney District features dozens of distinct venues, including Naples Ristorante e Bar, UVA Bar & Cafe, Marceline’s Confectionery, Black Tap Craft Burgers & Shakes, WonderGround Gallery, Disney Home, The LEGO Store, Wetzel’s Pretzels, Jamba and more. As they stroll the district, guests can appreciate the beautiful landscaping and colorful florals that adorn the Downtown Disney District. World of Disney: The flagship World of Disney store in the Downtown Disney District is a dynamic and distinctively Disney retail experience. Guests discover a spacious atmosphere inspired as an animators’ loft, with uniquely themed areas, pixie dust surprises in the decor, nods to the classics from Walt Disney Animation Studios and new merchandise collections. These innovative features reinforce World of Disney’s reputation as a must-visit destination for Disney fans, offering the largest selection of Disney toys, souvenirs, accessories, fashions and collectibles at the Disneyland Resort. Distinctive Dining: There are many food and beverage locations, outdoor patios and distinctive menus at the Downtown Disney District. Guests will find something for every taste—from exquisite meals at open-air cafés to gourmet treats. Recent additions include Salt & Straw, offering handmade ice cream in small batches using local, organic and sustainable ingredients, and Black Tap Craft Burgers & Shakes, serving award- winning burgers and over-the-top CrazyShake milkshakes. -

NARRATIVE ENVIRONMENTS from Disneyland to World of Warcraft

Essay Te x t Celia Pearce NARRATIVE ENVIRONMENTS From Disneyland to World of Warcraft In 1955, Walt Disney opened what many regard as the first-ever theme park in Anaheim, California, 28 miles southeast of Los Angeles. In the United States, vari- ous types of attractions had enjoyed varying degrees of success over the preceding 100 years. From the edgy and sometimes scary fun of the seedy seaside boardwalk to the exuberant industrial futurism of the World’s Fair to the “high” culture of the museum, middle class Americans had plenty of amusements. More than the mere celebrations of novelty, technology, entertainment and culture that preceded it, Disneyland was a synthesis of architecture and story (Marling 1997). It was a revival of narrative architecture, which had previously been reserved for secular functions, from the royal tombs of Mesopotamia and Egypt to the temples of the Aztecs to the great cathedrals of Europe. Over the centuries, the creation of narrative space has primarily been the pur- view of those in power; buildings whose purpose is to convey a story are expensive to build and require a high degree of skill and artistry. Ancient “imagineers” shared some of the same skills as Disney’s army of creative technologists: they understood light, space flow, materials and the techniques of illusion; they could make two dimensions appear as three and three dimensions appear as two; they understood the power of scale, and they developed a highly refined vocabulary of expressive techniques in the service of awe and illusion (Klein 2004). Like the creators of Disney- land, they built synthetic worlds, intricately planned citadels often set aside from the day-to-day bustle of emergent, chaotic cities or serving as a centerpiece of es- cape within them. -

Paris, Barcelona & Madrid

Learn more at eftours.com/girlscouts or call 800-457-9023 This is also your tour number PARIS, BARCELONA & MADRID 10 or 11 days | Spain | France How does La Sagrada Família compare to Notre-Dame? The Louvre to Puerta del Sol? Paris, Barcelona, and Madrid each offer world-class art and culture that, experienced together, will amaze you. From iconic architecture like the Eiffel Tower and Park Güell to savory regional cuisine like steak frites and paella, each day offers new and unforgettable experiences. YOUR EXPERIENCE INCLUDES: Full-time Tour Director Sightseeing: 3 sightseeing tours led by expert, licensed local guides; 1 walking tour Entrances: Royal Palace; Chocolate & churro experience; Park Güell; La Sagrada Família; Louvre; Sacré-Coeur Basilica; with extension: Disneyland Paris. weShare: Our personalized learning experience engages students before, during, and after tour, with the option to create a final, reflective project for academic credit. All of the details are covered: Round-trip flights on major carriers; comfortable motorcoach; TGV high-speed train; AVE high-speed train; 9 overnight stays in hotels with private bathrooms (10 with extension) DAY 1: FLY OVERNIGHT TO SPAIN DAY 2: MADRID – Meet your Tour Director at the airport. – Take an expertly guided tour of Madrid, Spain’s capital. With your Tour Director, you will see: Puerta del Sol; Plaza Mayor; Market of San Miguel. DAY 3: MADRID – Take a sightseeing tour of Madrid and visit the Royal Palace, the official residence of the Spanish Royal Family. – Take a break for a Spanish treat: chocolate and churros. Churros are a fried Spanish dessert traditionally accompanied with a cup of hot chocolate, or Café con Leche for dipping. -

Street, USA • Fantasyland• Continued Fantasyland• Frontierland

LEGE Guest Amenities Main Street, U.S.A. ® Frontierland® Fantasyland® Continued Wishes Tomorrowland® Restrooms nighttime spectacular Companion Restrooms 1 Walt Disney World ® Railroad ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS First Aid ® See the skies of the Magic 2 City Hall Home to Guest Relations, 14 Walt Disney World ® Railroad 25 Mickey’s PhilharMagic 35 Tomorrowland Speedway Presented by Florida Hospital ® Kingdom light up with this Information and Lost & Found. 3D movie. Presented by Kodak . 34 Drive a racecar. Minimum height 32"/81 cm; 15 Splash Mountain® nightly fireworks extravaganza Guest Relations Minimum height to ride alone 54"/137 cm. 3 Main Street Chamber of Commerce Plunge 5 stories into Brer Rabbit’s Laughin’ 26 Dream Along With Mickey that can be seen throughout ATMs Place. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. Presented by CHASE Package Pickup. Musical stage show. the entire Park! 32 36 Space Mountain® 23 33 Indoor roller coaster. Minimum height 44"/ 112 cm. Automated External 4 Town Square Theater 16 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad ® 27 Prince Charming Regal Carrousel See TIMES GUIDE. S Defibrillators Runaway train coaster. Meet Mickey Mouse and your favorite 37 Astro Orbiter ® Fly outdoors in a spaceship. Designated smoking area Disney Princesses! Presented by Kodak ®. Minimum height 40"/102 cm. 28 The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh 21 Fantasyland 30 31 Baby Care Center Roll, bounce and 38 Tomorrowland Transit Authority 5 Main Street Vehicles 17 Tom Sawyer Island float through indoor adventures (moments in 16 PeopleMover Roll through Locker rentals Come explore the Island. 6 Harmony Barber Shop the dark). FASTPASS kiosk located at Mickey’s Liberty Square 24 27 Tomorrowland. -

Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom Opens Its Ticketing Gates About an Hour Before Official Park Open

Gaston’s Tavern BARNSTORMER/ Dumbo FASTPASS Be JOURNEY OF Our Pete’s Guest QS/ TS THE LITTLE Silly MERMAID+ Sideshow Enchanted Tales with Walt Disney World Belle+ Railroad Station Ariel’s Haunted it’s a small world+ Pinocchio Mansion+ Village Grotto+ Haus BARNSTORMER+ Regal PETER Carrousel PAN+ DUMBO+ WINNIE Tea BIG THUNDER Columbia THE POOH+ MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Harbor House PRINCESS Party+ Square MAGIC+ MEET+ Walt Disney World Riverboat Railroad Station Tom Sawyer’s Hall of Pooh/ Island Presidents Mermaid FP Indy Sleepy Speedway+ Hollow Cinderella’s Cinderella Cosmic Royal Table Ray’s SPLASH Castle MOUNTAIN+ Liberty Diamond Tree SPACE MOUNTAIN+ H’Shoe Shooting Pecos Country Stitch Auntie Bill Arcade Astro Orbiter Golden Bears Gravity’s Oak Outpost Aloha Isle Tortuga Lunching Pad Tavern Tiki Room Swiss PeopleMover Aladdin’s Family Dessert Monsters Inc. Carpets+ Treehouse Party Laugh Floor+ BUZZ+ JUNGLE Crystal Casey’s Plaza Tomorrowland Pirates of CRUISE+ Palace Corner the Caribbean+ Rest. Terrace Carousel of Main St Progress Bakery SOTMK Tony’s Town Square City Hall MICKEY MOUSE MEET+ Railroad Station t ary Resor emopor Fr ont om Gr Monorail Station To C and Floridian Resor t Resort Bus Stop First Hour Attractions Boat Launch Ferryboat Landing First 2 Hours / Last 2 Hours of Operation Anytime Attractions Table Service Dining Quick Service Dining Shopping Restrooms Attractions labelled in ALL CAPS are FASTPASS enabled. Magic Kingdom Cheat Sheet Rope Drop: Magic Kingdom opens its ticketing gates about an hour before official Park open. Guests are held just inside the entrance in the courtyard in front of the train station. The opening show, which features Mickey and the gang arriving via steam train, begins 10 to 15 minutes prior to Park open and lasts about seven minutes. -

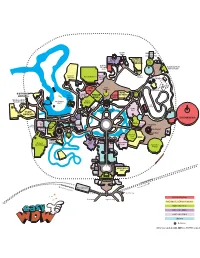

Street, Usa New Orleans Square

L MAIN STREET, U.S.A. FRONTIERLAND DISNEY DINING MICKEY’S TOONTOWN FANTASYLAND Restrooms 28 The Golden Horseshoe Companion Restroom ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS Chicken, fish, mozzarella strips, chili and ATTRACTIONS ATTRACTIONS Automated External 1 Disneyland® Railroad 22 Big Thunder Mountain Railroad 44 Chip ’n Dale Treehouse 53 Alice in Wonderland tasty ice cream specialties. Defibrillators 2 Main Street Cinema 29 Stage Door Café 45 Disneyland® Railroad 54 Bibbidi Bobbidi Boutique 55 Casey Jr. Circus Train E Information Center Main Street Vehicles* (minimum height 40"/102 cm) Chicken, fish and mozzarella strips. 46 Donald’s Boat Guest Relations presented by National Car Rental. 23 Pirate’s Lair on 30 Rancho del Zocalo Restaurante 47 Gadget’s Go Coaster 56 Dumbo the Flying Elephant (One-way transportation only) 57 Disney Princess Fantasy Faire Tom Sawyer Island* hosted by La Victoria. presented by Sparkle. First Aid (minimum height 35"/89 cm; 3 Fire Engine 24 Frontierland Shootin’ Exposition Mexican favorites and Costeña Grill specialties, 58 “it’s a small world” expectant mothers should not ride) ATM Locations 4 Horse-Drawn Streetcars 25 Mark Twain Riverboat* soft drinks and desserts. 50 52 presented by Sylvania. 49 48 Goofy’s Playhouse 5 Horseless Carriage 26 Sailing Ship Columbia* 31 River Belle Terrace 44 59 King Arthur Carrousel Pay Phones 49 Mickey’s House and Meet Mickey 60 Mad Tea Party 6 Omnibus (Operates weekends and select seasons only) Entrée salads and carved-to-order sandwiches. 48 51 47 50 Minnie’s House 61 Matterhorn Bobsleds Pay Phones with TTY 27 Big Thunder Ranch* 32 Big Thunder Ranch Barbecue 46 7 The Disney Gallery 51 Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin (minimum height 35"/89 cm) hosted by Brawny. -

Magic Kingdom

Mickey’s PhilharMagic Magic Kingdom 2 “it’s a small world” 8 ® 23 attractions ® 9 1 Mickey’s PhilharMagic – 1 0 Dumbo the Flying Elephant® – 5 Join Donald on a musical 3-D Soar over Fantasyland. 4 6 7 movie adventure through Disney classics. Theater does 1 1 The Barnstormer® – become dark at times with Take to the sky with the occasional water spurts. Flying Goofini. 1 2 Buzz Lightyear’s Space 10 3 11 ® 2 “it’s a small world” – Sail off Ranger Spin – Zap aliens and fantasyland on a classic voyage around the save the galaxy. world. Inspired by Disney•Pixar’s “Toy Story 2.” 3 Peter Pan’s Flight – Take a 1 Mickey’s PhilharMagic fl ight on a pirate ship. 1 3 Monsters, Inc. Laugh Floor – An ever-changing, 4 Cinderella’s Golden interactive giggle fest starring BIG THUNDER Carrousel – Take a magical Mike Wazowski. Inspired by MOUNTAIN RAILROAD Dumbo ride on an enchanted horse. Disney·Pixar’s “Monsters, Inc.” the Flying 24 5 Dumbo the Flying Elephant – 14 Walt Disney World® Railroad Elephant Soar the skies with Dumbo. – Hop a steam train that makes stops at Frontierland, 6 The Many Adventures of Mickey’s Toontown TOMORROWLAND Fair and frontierland® Winnie the Pooh – Visit the Main Street, U.S.A. INDY SPEEDWAY Hundred Acre Wood. 1 5 The Magic Carpets of 16 7 Mad Tea Party Aladdin tomorrowland® – Go for – Fly high over 19 a spin in a giant teacup. the skies of Agrabah. 20 8 Pooh’s Playful Spot – 1 6 Country Bear Jamboree – 18 Dream-Along With 21 Outdoor play break area.