Pakistan Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colour Khaki

tariq ali THE COLOUR KHAKI Now each day is fair and balmy, Everywhere you look: the army. Ustad Daman (1959) n 19 September 2001, General Pervaiz Musharraf went on TV to inform the people of Pakistan that their country Owould be standing shoulder to shoulder with the United States in its bombardment of Afghanistan. Visibly pale, blinking and sweating, he looked like a man who had just signed his own death warrant. The installation of the Taliban regime in Kabul had been the Pakistan Army’s only foreign-policy success. In 1978, the US had famously turned to the country’s military dictator General Zia-ul- Haq when it needed a proxy to manage its jihad against the radical pro-Soviet regime in Afghanistan. In what followed, the Pakistan Inter- Services Intelligence became an army within an army, with much of its budget supplied directly from Washington. It was the ISI that super- vised the Taliban’s sweep to power during Benazir Bhutto’s premiership of the mid-nineties; that controlled the infiltration of skilled saboteurs and assassins into Indian-held Kashmir; and that maintained a direct connexion with Osama bin Laden. Zia’s successors could congratulate themselves that their new province in the north-west almost made up for the defection of Bangladesh in 1971. Now it was time to unravel the gains of the victory: the Taliban pro- tectorate had to be dismantled and bin Laden captured, ‘dead or alive’. But having played such a frontline role in installing fundamentalism in Afghanistan, would the Pakistan Army and the ISI accept the reverse command from their foreign masters, and put themselves in the fore- front of the brutal attempt to root it out? Musharraf was clearly nervous new left review 19 jan feb 2003 5 6 nlr 19 but the US Defence Intelligence Agency had not erred. -

Pld 2017 Sc 70)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Original Jurisdiction) PRESENT: Mr. Justice Asif Saeed Khan Khosa Mr. Justice Ejaz Afzal Khan Mr. Justice Gulzar Ahmed Mr. Justice Sh. Azmat Saeed Mr. Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan Constitution Petition No. 29 of 2016 (Panama Papers Scandal) Imran Ahmad Khan Niazi Petitioner versus Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, Prime Minister of Pakistan / Member National Assembly, Prime Minister’s House, Islamabad and nine others Respondents For the petitioner: Syed Naeem Bokhari, ASC Mr. Sikandar Bashir Mohmad, ASC Mr. Fawad Hussain Ch., ASC Mr. Faisal Fareed Hussain, ASC Ch. Akhtar Ali, AOR with the petitioner in person Assisted by: Mr. Yousaf Anjum, Advocate Mr. Kashif Siddiqui, Advocate Mr. Imad Khan, Advocate Mr. Akbar Hussain, Advocate Barrister Maleeka Bokhari, Advocate Ms. Iman Shahid, Advocate, For respondent No. 1: Mr. Makhdoom Ali Khan, Sr. ASC Mr. Khurram M. Hashmi, ASC Mr. Feisal Naqvi, ASC Assisted by: Mr. Saad Hashmi, Advocate Mr. Sarmad Hani, Advocate Mr. Mustafa Mirza, Advocate For the National Mr. Qamar Zaman Chaudhry, Accountability Bureau Chairman, National Accountability (respondent No. 2): Bureau in person Mr. Waqas Qadeer Dar, Prosecutor- Constitution Petition No. 29 of 2016, 2 Constitution Petition No. 30 of 2016 & Constitution Petition No. 03 of 2017 General Accountability Mr. Arshad Qayyum, Special Prosecutor Accountability Syed Ali Imran, Special Prosecutor Accountability Mr. Farid-ul-Hasan Ch., Special Prosecutor Accountability For the Federation of Mr. Ashtar Ausaf Ali, Attorney-General Pakistan for Pakistan (respondents No. 3 & Mr. Nayyar Abbas Rizvi, Additional 4): Attorney-General for Pakistan Mr. Gulfam Hameed, Deputy Solicitor, Ministry of Law & Justice Assisted by: Barrister Asad Rahim Khan Mr. -

July 16, 2017

INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES eekly E-BULLETINE-BULLETIN PAKISTAN PROJECT w July 10-26, 2017 This E-Bulletin focuses on major developments in Pakistan on weekly basis and brings them to the notice of strategic analysts and policy makers in India. EDITORIAL The Sharif family has rejected the JIT report and argued that the team had exceeded its mandate. Nawaz Sharif ’s he Joint Investigation Team (JIT) report has created lawyer Khawaja Haris, raised his objections in the Ta lot of speculation regarding the future of Prime Supreme Court on July 17 and dismissed the JIT report Minister Nawaz Sharif. While there was speculation as “eyewash” based on “mala fide” intentions and about the likely successor to Prime Minister Sharif, it “undertaken with a predisposed mind to malign and appears that he would not resign without giving a fight implicate the respondents in some wrongdoing or the - a stand supported by the party. The Supreme Court is other,” hearing the Panama papers case and examining the JIT report. It has also asked Imran Khan, the Chairperson The opposition, on the contrary, regards the report as of the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf, to explain the financial an incontrovertible proof of illegal money laundering source of his London flat. The political uncertainty also by the Sharif family and wants Nawaz to quit on moral reflected in the stock market as the market plummeted. grounds. As Nawaz refuses to resign, the opposition KSE-100 index declined 885 points (1.96 per cent) and hopes that the Supreme Court will ultimately find Nawaz settled at the end of the week at 44,337 points. -

The Removal of Nawaz Sharif and Changing Role of Punjab in Pakistani Politics

December 2014 15 August 2017 The Removal of Nawaz Sharif and Changing Role of Punjab in Pakistani Politics Tridivesh Singh Maini FDI Associate Key Points The removal from office of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif could be the precedent for a change of approach towards the civil-military relationship on the part of the influential province of Punjab. The most populous province of Pakistan, Punjab has long dominated the Pakistani polity and military. Sharif’s party, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz), heads both the Punjab provincial government and the national government. If the PML-N decides to continue Sharif’s attempts at better relations with India, it will again place the government at odds with the army, which wants oversight of foreign policy issues pertaining to Afghanistan and India. If the PML-N is interested in improving links with India, it will need to take action against terrorist groups. Summary The most populous province of Pakistan, Punjab has long dominated the Pakistani polity and military. Initially, at least, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif – a Punjabi – enjoyed a close relationship with the army. That relationship soured, however, following his dismissal from office during his first term as Prime Minister in 1993. A key factor for the falling out between Sharif and the army was the former’s attempts to build a better relationship with India. Arguably, that enmity only increased during Sharif’s third, most recent, term in office. In the wake of Sharif’s disqualification on 28 July 2017, the influential, traditionally pro-army Punjab leadership is now instead backing Sharif’s party, the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz), or PML-N. -

The Sharif Verdict

8/7/2017 The Sharif Verdict The Sharif Verdict Suba Chandran Pakistan is trying to digest the Supreme Court ruling on disqualifying Nawaz Sharif as the Prime Minister. So is PML-N – trying to cope up with the situation and looking at alternatives. While Imran Khan is jubilant, other opposition political parties are guarded in their response. A section within Pakistan feels that this judgement – disqualifying a sitting Prime Minister (though some talk in terms of a “judicial coup”) as a new great beginning for the judiciary and accountability for Pakistan; this section also expects the Supreme Court to continue and expand further. And the elephant in the room- the military has been quiet. What next? What would be individual Endgames for these actors? And where would these individual Endgames collectively take Pakistan into? PML-N: Getting ready for the transition. Or, will it transform? The PML-N has been extremely critical of the entire process led Joint Investigation Team; many within the party questioned the motivations of the JIT. A section even accused of conspiracy by some members of the JIT in misleading the process, and in the process projecting the entire Sharif family in a bad light. And there is an element of truth in the above perception. However, Nawaz Sharif has accepted the Supreme Court’s verdict and has decided to immediately step down. A care taker Prime Minister has been already chosen. It is widely expected that Shabaz Sharif, Nawaz’s younger brother and currently the Chief Minister of Punjab province will resign and contest for the National Assembly, and subsequently get appointed as the Prime Minister. -

A Study of Pakistan's Political Parties' Control Over State Resources and Redistribution in the Light of Panama Papers

International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 6 No. 12 December 2018 A Study of Pakistan’s Political Parties’ Control Over State Resources and Redistribution in the Light of Panama Papers Spozmi TOOR Istanbul Aydin University Abstract The aim of the paper is to analyze and summarize the existing theoretical and secondary work on corruption in Pakistan. Two of the major political parties’ (PMLN and PPP) tenures will be discussed as they have ruled the country for about 30 years. Additionally, their control over the resources will be highlighted and how they have paved ways for corruption in every institution. The paper begins with a brief over-view of conceptualization of Corruption. This is followed by the major corruption leaks known as ‘Panama Papers’ which caused a bustle in Pakistani politics as one of the prominent political parties’ (PMLN) head and his family was named in those leaks that how they have been over the years money laundering to buy hidden off shore companies. The paper also addresses the important aspect of corruption and improper allocation of country’s resources with regards to the most powerful political parties of Pakistan PPP and PMLN. It discusses the most important factors of corruption with regards to the parties’ exercise within the parliament, election campaign, and overall control of the party over the resources of the country and its redistribution. Keywords: Corruption, Panama leaks, Pakistan, Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz Party, Pakistan people’s party, State 227 ISSN: 2411-5681 www.ijern.com Introduction The topic of my paper is “Pakistan Political Parties’ Control over State Resources and Redistribution in the Light of Panama Papers”. -

Jenni Russel Greater Turmoil Is Expected

SUCCESS IS A LOUSY TEACH- QUOTE ER. IT SEDUCES SMART OF THE PEOPLE INTO THINKING THEY DAY CAN’T LOSE. Thursday, July 12, 2018 BILL GATES Johnson JENNI RUSSELL or the second time in three years, Boris Johnson, a politician whose ambition and Fsuperficial charm far outstrip his ability, judgment or principles, is destabilising the British has government and threatening the country’s future. On July 9, Johnson, in protest against Prime Minister Theresa May’s plans for Brexit, resigned from his post as foreign secretary. Now May’s authority, longevity and ability to deliver a Brexit without causing an economic crisis are in question. But further political paralysis seems certain. ruined Britain is in this mess principally because the Brexiteers — led largely by Johnson — sold the country a series of lies in the lead up to the June 2016 referendum on leaving the European Union. They did so because neither Johnson nor his fel- low leader of the “leave” campaign, Michael Gove, intended, wanted or expected to win. Britain At the start of 2016, Johnson was perhaps the most popular politician in Britain. Supporters and fans mobbed him at train stations and traffic lights; pollsters and pundits thought he could reach the parts of the country that other Conservatives could never touch. But he was also driven and insecure, ‘He knows that the verdict of so desperate to guarantee he would be the next prime minister that he cynically abandoned his history is about to come down on own previous positions on the European Union him - and bury him’ in order to try to secure support from his party’s Euroskeptic right wing. -

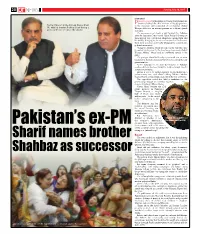

Sharif Names Brother

20 Sunday, July 30, 2017 Islamabad akistan’s ousted prime minister Nawaz Sharif named his brother Shahbaz, the chief minister of Punjab province, Former Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif asP his successor and nominated ex-oil minister Shahid (R) with his brother Shahbaz Sharif during a Khaqan Abbasi as an interim premier in a defiant speech press conference in Lahore (file photo) yesterday. The announcement charts a way forward for Pakistan after the Supreme Court ousted Sharif Friday following an investigation into corruption allegations against him and his family, bringing to an unceremonious end his historic third term in power and briefly plunging the country into political uncertainty. “I support Shahbaz Sharif after me but he will take time to contest elections so for the time being I nominate Shahid Khaqan Abbasi,” Sharif said in a televised speech to his party. The younger Sharif holds only a provincial seat, so must be elected to the national assembly before becoming the new prime minister. Earlier Saturday the Election Commission of Pakistan confirmed fresh elections would be held in Nawaz Sharif’s former constituency. Abbasi is set to be rubber-stamped as placeholder in a parliamentary vote, with Sharif’s ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz commanding a majority in the 342-seat house. The opposition could also field a candidate for the premiership, though the nominee has little chance of getting sufficient votes. Nawaz Sharif became the 15th prime minister in Pakistan’s 70-year history -- roughly half of which was under military rule -- to be ousted before completing a full term. -

What Hudaibiya Case Is and How It Started

What Hudaibiya case is and how it started Now when the Supreme Court is going to take up NAB’s appeal for reopening Hudaibiya Paper Mills case, many still have no fair idea of its origin, scale and implications. It’s about alleged fraud of over 1,242 million—an amount that makes it bigger in scale than Panama Papers case. The case started in March 2000 when the NAB authorities moved a reference against Hudaibiya Papers Mills. Besides his other relatives and associates, ousted prime minister Nawaz Sharif and his two children – Maryam and Hussain – are among the accused. In contrast with Panama case, Punjab Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif and his political heir- apparent Hamza Shehbaz is also accused in this case – something that gives a new dimension to the ongoing process of accountability of the ruling family, making it even wider and more troubling for the Sharifs. Incumbent Finance Minister Ishaq Dar was also nominated in the NAB’s reference for opening fictitious (benami) foreign currency accounts to help the family commit fraud. Dar turned approver in the case, but later retracted his statement given against the Sharifs claiming it was extracted under duress. Modus operandi of ‘fraud’ During scrutiny of the record pertaining to the accounts of M/SHudaibiya Papers Mills Ltd (HPML) for the year 1996-97 and 1997-98, NAB Chief Executive Secretariat Islamabad observed that a sum of Rs30.499 million and Rs612. 273 million in respective years was shown as share deposit money. Such a huge influx of investments in a company whose share capital prior to this addition was only Rs95.7 million and which was carrying huge accumulated losses to the tune of Rs809.834 million, raised serious doubts about the bona fide of this investment. -

Pakistan Apr2001

PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY General 2.1 - 2.3 Languages 2.4 Economy 2.5 III HISTORY 1947-1978 3.1 – 3.4 1978-1988 3.5 – 3.8 1988-1993 3.9 – 3.15 1993-1997 3.16 – 3.27 1998-September 1999 3.28 – 3.39 October 1999 - December 2000 3.40– 3.45 January 2001 - April 2001 3.46– 3.49 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE 4.1 POLITICAL SYSTEM Political Structure 4.1.1 – 4.1.3 Constitution 4.1.4 Government 4.1.5 – 4.1.9 Main Political Parties Following the Coup 4.1.10 – 4.1.14 President 4.1.15 Federal Legislature 4.1.16 – 4.1.17 Election Results 4.1.18 – 4.1.19 4.2 JUDICIAL SYSTEM Introduction 4.2.1 – 4.2.4 Court System 4.2.5 – 4.2.7 Anti-Terrorism Act and Courts 4.2.8 – 4.2.12 Federal Administered Tribal Areas 4.2.13 Sharia Law 4.2.14 – 4.2.16 - Hadood Ordinances 4.2.17 – 4.2.18 - Qisas and Diyat Ordinances 4.2.19 – 4.2.20 - Blasphemy Law 4.2.21 – 4.2.26 - Death Penalty 4.2.27 – 4.2.29 Accountability Commission 4.2.30 – 4.2.33 National Accountability Bureau (NAB) 4.2.34 – 4.2.39 4.3 SECURITY General 4.3.1 – 4.3.3 Sindh 4.3.4 – 4.3.5 Punjab 4.3.6 2 V HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 – 5.1.2 5.2 GENERAL ASSESSMENT Police 5.2.1 – 5.2.5 Arbitrary Arrest 5.2.6 – 5.2.7 Torture 5.2.8 – 5.2.9 Human Rights Groups 5.2.10 – 5.2.11 5.3 SPECIFIC GROUPS Religious Minorities - Background 5.3.1 – 5.3.3 - Policies and Constitutional Provisions 5.3.4 – 5.3.11 - Voting Rights 5.3.12 – 5.3.14 Ahmadis - Introduction 5.3.15 – 5.3.18 - Ahmadi Headquarters, Rabwah 5.3.19 - Legislative -

Abstract Conflicts in Leading Urdu Pakistani Newspapers During

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2020(V-IV).11 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2020(V-IV).11 Citation: Karamat, K., Saleem, N., & Arshad, T. (2020). An Analysis of National Political Conflicts in Leading Urdu Pakistani Newspapers during 2015-17. Global Political Review, V(IV), 94-104. doi:10.31703/gpr.2020(V-IV).11 Vol. V, No. IV (Fall 2020) Pages: 94 – 104 An Analysis of National Political Conflicts in Leading Urdu Pakistani Newspapers during 2015-17 Kiran Karamat* Noshina Saleem† Tahseen Arshad‡ p- ISSN: 2520-0348 e- ISSN: 2707-4587 p- ISSN: 2520-0348 This study investigates Analysis of National Political Abstract Conflicts in Leading Urdu Pakistani Newspapers during Headings 2015-17. The main aim of this study was to explore the analysis of national political conflicts in selected newspapers. Framing theory was • Abstract applied to study the newspaper's treatment of political conflicts as a • Key Words theoretical baseline. Two leading Urdu newspapers Daily Jang and • Introduction Nawa-i-Waqt, due to their circulation and readership and a valuable • Historical Background amount of information for researchers and scholars, were selected for • Methodology content analysis by using purposive sampling from the period of 2015 to • Polio in Pakistan 2017. Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 21); hence, the findings • COVID19, polio Vaccination and revealed that there is a significant association between newspapers Pakistan • Result and Discussion analysis and national political conflicts. • Conclusion • References Key Words: Analysis, National Political Conflicts, Leading Urdu Pakistani Newspapers, Framing theory, Content Analysis Introduction The present study examines coverage of national political conflicts in Pakistani print media. -

Pakistan: Situation Der Ahmadi

Pakistan: Situation der Ahmadi Schnellrecherche der SFH-Länderanalyse Bern, 7. Mai 2018 Impressum Herausgeberin Schweizerische Flüchtlingshilfe SFH Postfach, 3001 Bern Tel. 031 370 75 75 Fax 031 370 75 00 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.fluechtlingshilfe.ch Spendenkonto: PC 30-1085-7 Sprachversionen Deutsch, französisch Copyright © 2018 Schweizerische Flüchtlingshilfe SFH, Bern Kopieren und Abdruck unter Quellenangabe erlaubt. 1 Einleitung Einer Anfrage an die SFH-Länderanalyse sind die folgenden Fragen entnommen: 1. Welche Informationen gibt es bezüglich der aktuellen Situation der Ahmadi , einschliess- lich in der Provinz Punjab? 2. Inwiefern hat sich ihre Situation in den Jahren 2016, 2017 und 2018 verschlechtert? Die Informationen beruhen auf einer zeitlich begrenzten Recherche (Schnellrecherche) in öffentlich zugänglichen Dokumenten, die der SFH derzeit zur Verfügung stehen, sowie auf den Informationen von sachkundigen Kontaktpersonen. 2 Situation der Ahmadi 2.1 Rechtlicher Rahmen, staatliche Verantwortung Hintergrundinformationen zur Ahmadi-Gemeinschaft. Gemäss den UNHCR-Richtlinien zur Einschätzung des internationalen Schutzbedarfs von Mitgliedern religiöser Minderheiten in Pakistan vom Januar 2017 und New York Times (NYT, 19. Oktober 2017) wurde die Ahmadi-Bewegung (Ahmadiyya Jama’at) 1889 in der Stadt Qadian im heute indischen Teil von Punjab als Reformbewegung innerhalb des Islam gegründet. Schätzungen zur Zahl der Ahmadi in Pakistan reichen gemäss UNHCR (Januar 2017) von 126‘000 bis mehrere Millio- nen. NYT (19. Oktober 2017) berichtet von Schätzungen zwischen 500‘000 und vier Millio- nen; viele Ahmadi identifizierten sich in der Öffentlichkeit nicht als Ahmadi, andere nähmen nicht an Volkszählungen teil. Laut NYT (19. Oktober 2017) werden Ahmadi auch als Qadiani bezeichnet, was sie selbst als abwertend empfänden.