Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

Spanish American, 03-30-1912 Roy Pub

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Spanish-American, 1905-1922 (Roy, Mora County, New Mexico Historical Newspapers New Mexico) 3-30-1912 Spanish American, 03-30-1912 Roy Pub. Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sp_am_roy_news Recommended Citation Roy Pub. Co.. "Spanish American, 03-30-1912." (1912). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sp_am_roy_news/17 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish-American, 1905-1922 (Roy, Mora County, New Mexico) by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. f! i ' ti HOT LI3RAW r OMVERSnY DF m!C0 CU UOlú i svg a' t r r -- -- Í a. 1 1 i j Ü J I j IVf Vol. IX ROY, MORA COUNTY. NEW MEXICO, SATURDAY, MARCH 30. 1912. No. 10 CATRON BRIBERY CASE TRAGEDY IN FAIL MD Declaration of ; Principles of the - ABOUT COMPLETED ELECTED SENATORS Progressive Republican League SPRCIGER. of the State of New Mexico Arrest of Bribe-Take-rs was Result of a Conspiracy, Andrews and Mills Withdraw from the Senatorial Race Cleverly Planned. Mrs. Lewis B. Speers Shoots in Favor of Same Candidate, Making it Possible for . The objects of this league are the promotion of the follow- Herself Following Arrest ing principles. , for Failure to pay Board Election of Fall and Catron. Santa Fe., N. M., March 27. 1. We believe in the language of Abraham Lincoln that BUL Contrary to expectations, it will "This is a government of the people, by the people, and for the take two more' days before the people." . -

Westmorland and Cumbria Bridge Leagues February

WBL February Newsletter 1st February 2021 Westmorland and Cumbria Bridge Leagues February Newsletter 1 WBL February Newsletter 1st February 2021 Contents Congratulations to All Winners in the January Schedule .................................................................................................. 3 A Word from your Organiser ............................................................................................................................................ 5 February Schedule ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Teams and Pairs Leagues .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Teams Events ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Cumbria Inter-Club Teams of Eight ........................................................................................................................... 7 A Word from the Players................................................................................................................................................... 8 From Ken Orford ........................................................................................................................................................... 8 From Jim Lawson ........................................................................................................................................................ -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

New Books on Art & Culture

S11_cover_OUT.qxp:cat_s05_cover1 12/2/10 3:13 PM Page 1 Presorted | Bound Printed DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS,INC Matter U.S. Postage PAID Madison, WI Permit No. 2223 DISTRIBUTEDARTPUBLISHERS . SPRING 2011 NEW BOOKS ON SPRING 2011 BOOKS ON ART AND CULTURE ART & CULTURE ISBN 978-1-935202-48-6 $3.50 DISTRIBUTED ART PUBLISHERS, INC. 155 SIXTH AVENUE 2ND FLOOR NEW YORK NY 10013 WWW.ARTBOOK.COM GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 SPRING HIGHLIGHTS ArtHistory 64 Art 76 BookDesign 88 Photography 90 Writings&GroupExhibitions 102 Architecture&Design 110 Journals 118 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Special&LimitedEditions 124 Art 125 GroupExhibitions 147 Photography 157 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Architecture&Design 169 Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production Nicole Lee BacklistHighlights 175 Data Production Index 179 Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Sara Marcus Cameron Shaw Eleanor Strehl Printing Royle Printing Front cover image: Mark Morrisroe,“Fascination (Jonathan),” c. 1983. C-print, negative sandwich, 40.6 x 50.8 cm. F.C. Gundlach Foundation. © The Estate of Mark Morrisroe (Ringier Collection) at Fotomuseum Winterthur. From Mark Morrisroe, published by JRP|Ringier. See Page 6. Back cover image: Rodney Graham,“Weathervane (West),” 2007. From Rodney Graham: British Weathervanes, published by Christine Burgin/Donald Young. See page 87. Takashi Murakami,“Flower Matango” (2001–2006), in the Galerie des Glaces at Versailles. See Murakami Versailles, published by Editions Xavier Barral, p. 16. GENERAL INTEREST 4 | D.A.P. | T:800.338.2665 F:800.478.3128 GENERAL INTEREST Drawn from the collection of the Library of Congress, this beautifully produced book is a celebration of the history of the photographic album, from the turn of last century to the present day. -

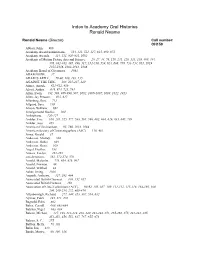

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame

Index to Academy Oral Histories Ronald Neame Ronald Neame (Director) Call number: OH159 Abbott, John, 906 Academy Award nominations, 314, 321, 511, 517, 935, 969, 971 Academy Awards, 314, 511, 950-951, 1002 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science, 20, 27, 44, 76, 110, 241, 328, 333, 339, 400, 444, 476, 482-483, 495, 498, 517, 552-556, 559, 624, 686, 709, 733-734, 951, 1019, 1055-1056, 1083-1084, 1086 Academy Board of Governors, 1083 ADAM BEDE, 37 ADAM’S APPLE, 79-80, 100, 103, 135 AGAINST THE TIDE, 184, 225-227, 229 Aimee, Anouk, 611-612, 959 Alcott, Arthur, 648, 674, 725, 784 Allen, Irwin, 391, 508, 986-990, 997, 1002, 1006-1007, 1009, 1012, 1013 Allen, Jay Presson, 925, 927 Allenberg, Bert, 713 Allgood, Sara, 239 Alwyn, William, 692 Amalgamated Studios, 209 Ambiphone, 126-127 Ambler, Eric, 166, 201, 525, 577, 588, 595, 598, 602, 604, 626, 635, 645, 709 Ambler, Joss, 265 American Film Institute, 95, 766, 1019, 1084 American Society of Cinematogaphers (ASC), 118, 481 Ames, Gerald, 37 Anderson, Mickey, 366 Anderson, Robin, 893 Anderson, Rona, 929 Angel, Heather, 193 Ankers, Evelyn, 261-263 anti-Semitism, 562, 572-574, 576 Arnold, Malcolm, 773, 864, 876, 907 Arnold, Norman, 88 Arnold, Wilfred, 88 Asher, Irving, 1026 Asquith, Anthony, 127, 292, 404 Associated British Cinemas, 108, 152, 857 Associated British Pictures, 150 Association of Cine-Technicians (ACT), 90-92, 105, 107, 109, 111-112, 115-118, 164-166, 180, 200, 209-210, 272, 469-470 Attenborough, Richard, 277, 340, 353, 387, 554, 632 Aylmer, Felix, 185, 271, 278 Bagnold, Edin, 862 Baker, Carroll, 680, 883-884 Balchin, Nigel, 683, 684 Balcon, Michael, 127, 198, 212-214, 238, 240, 243-244, 251, 265-266, 275, 281-282, 285, 451-453, 456, 552, 637, 767, 855, 878 Balcon, S. -

View Catalogue

BOW WINDOWS BOOKSHOP 175 High Street, Lewes, Sussex, BN7 1YE T: +44 (0)1273 480 780 F: +44 (0)1273 486 686 [email protected] bowwindows.com CATALOGUE TWO HUNDRED AND ELEVEN Literature - First Editions, Classics, Private Press 1 - 89 Children's and Illustrated Books 90 - 107 Natural History 108 - 137 Maps 138 - 154 Travel and Topography 155 - 208 Art and Architecture 209 - 238 General Subjects - History, Theology, Militaria 239 - 264 Cover images – nos. 93 & 125 All items are pictured on our website and further images can be emailed on request. All books are collated and described as carefully as possible. Payment may be made by cheque, drawn on a sterling account, Visa, MasterCard or direct transfer to Account No. 40009652 at HSBC Bank, Eastbourne, sort code 40-20-69. Our IBAN code is GB02 HBUK40206940009652; SWIFTBIC is MIDL GB22. Postage will be charged at cost. Foreign orders will be sent by airmail unless requested otherwise. Our shop hours are 9.30 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Saturday; an answerphone operates outside of these times. Items may also be ordered via our website. Ric Latham and Jonathan Menezes General Data Protection Regulation We hold on our computer our customers names and addresses, and in some cases phone numbers and email addresses. We do not share this information with third parties. We assume that you will be happy to continue to receive these catalogues and for us to hold this information; should you wish to change anything or come off our mailing list please let us know. LITERATURE FIRST EDITIONS, CLASSICS, PRIVATE PRESS 1. -

508642 VOL2.Pdf

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Lord Berners : Aspects of a Biography Gifford, Mary The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 LORD BERNERS: ASPECTS OF A BIOGRAPHY Name: MARY GIFFORD College: KING'S COLLEGE LONDON, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Examination: PhD VOLUME2 Selected bibliography 186 Published music by Berners 200 Recorded music 204 Tables (working documents) 1. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

HP0221 Teddy Darvas

BECTU History Project - Interview No. 221 [Copyright BECTU] Transcription Date: Interview Dates: 8 November 1991 Interviewer: John Legard Interviewee: Teddy Darvas, Editor Tape 1 Side A (Side 1) John Legard: Teddy, let us start with your early days. Can you tell us where you were born and who your parents were and perhaps a little about that part of your life? The beginning. Teddy Darvas: My father was a very poor Jewish boy who was the oldest of, I have forgotten how many brothers and sisters. His father, my grandfather, was a shoemaker or a cobbler who, I think, preferred being in the cafe having a drink and seeing friends. So he never had much money and my father was the one brilliant person who went to school and eventually to university. He won all the prizes at Gymnasium, which is the secondary school, like a grammar school. John Legard: Now, tell me, what part or the world are we talking about? Teddy Darvas: This is Budapest. He was born in Budapest and whenever he won any prizes which were gold sovereigns, all that money went on clothes and things for brothers and sisters. And it was in this Gymnasium that he met Alexander Korda who was in a parallel form. My father was standing for Student's Union and he found somebody was working against him and that turned out to be Alexander Korda, of course the family name was Kelner. They became the very, very greatest of friends. Alex was always known as Laci which is Ladislav really - I don't know why. -

The WOODEN HORSE

fc*.J 1 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ;ff$0 THK WAYKARKR-S LIBRARY The WOODEN HORSE Hugh Walpole f M. DLNT '^ SOKS. ! t,i College Library TO W. FERRIS AFFECTIONATELY " Er liebte jeden Hund, und wiinschte von jedem Hund tu sein." FLEGELJAHRE (]EAN PAUL). THE WOODEN HORSE CHAPTER I ROBIN TROJAN was waiting for his father. Through the open window of the drawing-room came, faintly, the cries of the town the sound of some distant bell, the shout of fishermen on the quay, the muffled beat of the mining-stamps from Porth- Vennic, a village that lay two miles inland. There yet lingered in the air the faint afterglow of the sun- set, and a few stars, twinkling faintly in the deep blue of the night sky, seemed reflections of the orange lights of the herring-boats, flashing far out to sea. The great drawing-room, lighted by a cluster of electric lamps hanging from the ceiling, seemed to flaunt the dim twinkle of the stars contemptuously; the dark blue of the walls and thick Persian carpets sounded a quieter note, but the general effect was of something distantly, coldly superior, something indeed that was scarcely comfortable, but that was, nevertheless, fulfilling the exact purpose for which it had been intended. And that purpose was, most certainly, not comfort. 3 The Wooden Horse Robin himself would have smiled contemptuously if you had pleaded for something homely, something suggestive of roaring fires and cosy armchairs, instead of the stiff-backed, beautifully carved Louis XIV. furniture that stood, each chair and table rigidly in its appointed place, as though bidding defiance to any one bold enough to attempt alterations.