Program Linguistic Variation South America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice Under Pressure – Repressions As a Means of Attempting to Take Control Over the Judiciary and the Prosecution in Poland

IUSTITIA RAPORTY Justice under pressure – repressions as a means of attempting to take control over the judiciary and the prosecution in Poland. Years 2015–2019 Edited by Jakub Kościerzyński Prepared by: sędzia SA Michał Bober sędzia SO Piotr Gąciarek sędzia SR Joanna Jurkiewicz sędzia SR Jakub Kościerzyński prokurator PR Mariusz Krasoń sędzia SR Dorota Zabłudowska Th e report was drawn up by judges from the Polish Judges’ Association “Iustitia” and by a prosecutor from the “Lex Super Omnia” Association of Prosecutors. “Iustitia” is the largest association of judges in Poland. It is fully independent, apolitical and self-governing, with over 3500 members, which is over 1/3 of the total number of judges. Our main mission is to defend the principles of a democratic state of law: freedom, rights and civil liberties, which are the cornerstone of democratic Poland. We are active in many fi elds not only throughout Poland but also in the international arena as a member of international associations of judges (IAJ, EAJ, MEDEL). “Lex Super Omnia” is fully independent, apolitical and self-governing. It brings together more than 200 prosecutors. Th e main goal of the association is to strive for establishing an independent prosecution, the position of which is defi ned in the Polish Constitution. ISBN: 978-83-920641-8-3 Spis treści Introduction ................................................................................................................. 7 Part I. Judges ............................................................................................................... 9 Chapter I. List of judges against whom the disciplinary prosecutor of common courts, judge Piotr Schab and his deputies, judges: Michał Lasota and Przemysław W. Radzik, have launched investigations or initiated disciplinary proceedings in connection with judicial and extrajudicial activities. -

Private Car “The Kashubian's Region” Tour with Museum from Hotel & Also

Private car “The Kashubian’s Region” tour with Museum from hotel & also includes private car return airport transfers (2 Sharing) - £55pp Private Tour Includes: Return private car airport transfers Private Tour Guide with extensive knowledge of the area. Tour in the Kashubian’s Region. Entry to biggest open air museum for 2 Adults. Visit to Kashubian Centre. Dinner in local restaurant -Optional (extra charges apply). Tour Guide: Mr. Jacek Waldoch Features: About me: I am passionate about Gdansk & its history & Tour in English surroundings. I am professional guide with a certificate from Flexible time. Stutthof Museum. Museum ticket & parking fares included. Information about local cuisines & recommendations. Pick up & return to Hotel directly with private car. Includes return private car transfers to airport (normally costs £25 pp) Duration (approx.): 5 Hours – 6 Hours. Friendly atmosphere. Ceramics has a centuries-old tradition in Kashubia, and again the designs are simple. Kashubian ceramics are decorated with a number of traditional designs including the Kashubian star, fish scales and local flowers, all embellished with wavy lines and dots. The Kashubians are also great weavers, even managing to weave buckets and jugs from pine roots and straw capable of holding water. Their weaving skills can also be seen on the roofs of the many thatched houses in the region. The Kashubians are also well known for a style of primitive painting on glass, woodcuts, and wooden sculptures including roadside chapels known as the Passions of Christ. Wood is also carved into elaborate walking sticks, animal heads and musical instruments, including the extraordinary burczybas, similar to a double bass but in the shape of a barrel with a horse hair tail. -

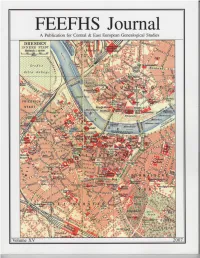

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

Regional Investment Attractiveness 2014

Warsaw School of Economics REGIONAL INVESTMENT ATTRACTIVENESS 2014 Western Pomeranian Voivodship Hanna Godlewska-Majkowska, Ph.D., Associate Professor at the Warsaw School of Economics Agnieszka Komor, Ph.D. 3DWU\FMXV]=DUĊEVNL3K' Mariusz Czernecki, M.A. Magdalena Typa, M.A. Report prepared for the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency at the Institute of Enterprise, Warsaw School of Economics Warsaw, December 2014 2014 Regional investment attractiveness 2014 Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency (PAIiIZ) is a governmental institution and has been servicing investors since 1992. Its mission is to create a positive image of Poland in the world and increase the inflow of foreign direct investments by encouraging international companies to invest in Poland. PAIiIZ is a useful partner for foreign entrepreneurs entering the Polish market. The Agency guides investors through all the essential administrative and legal procedures that involve a project. It also provides rapid access to complex information relating to legal and business matters regarding investments. Moreover, it helps in finding the appropriate partners and suppliers together with new locations. PAIiIZ provides free of charge professional advisory services for investors, including: investment site selection in Poland, tailor-made investors visits to Poland, information on legal and economic environment, information on available investment incentives, facilitating contacts with central and local authorities, identification of suppliers and contractors, care of existing investors (support of reinvestments in Poland). Besides the OECD National Contact Point, PAIiIZ also maintains an Information Point for companies ZKLFK DUH LQWHUHVWHG LQ (XURSHDQ )XQGV $OO RI WKH $JHQF\¶V DFWLYLWLHV DUH VXSSRUWHG E\ WKH Regional Investor Assistance Centres. Thanks to the training and ongoing support of the Agency, the Centres provide complex professional services for investors at voivodship level. -

Scripta Islandica 65/2014

SCRIPTA ISLANDICA ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 65/2014 REDIGERAD AV LASSE MÅRTENSSON OCH VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON GÄSTREDAKTÖRER JONATHAN ADAMS ALEXANDRA PETRULEVICH HENRIK WILLIAMS under medverkan av Pernille Hermann (Århus) Else Mundal (Bergen) Guðrún Nordal (Reykjavík) Heimir Pálsson (Uppsala) UPPSALA, SVERIGE Publicerad med stöd från Vetenskapsrådet. © Författarna och Scripta Islandica 2014 ISSN 0582-3234 Sättning: Ord och sats Marco Bianchi urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-235580 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-235580 Contents Preface ................................................. 5 ÞÓRDÍS EDDA JÓHANNESDÓTTIR & VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON, The Manu- scripts of Jómsvíkinga Saga: A Survey ...................... 9 Workshop Articles SIRPA AALTO, Jómsvíkinga Saga as a Part of Old Norse Historiog - raphy ................................................ 33 Leszek P. słuPecki, Comments on Sirpa Aalto’s Paper ........... 59 ALISON FINLAY, Jómsvíkinga Saga and Genre ................... 63 Judith Jesch, Jómsvíkinga Sǫgur and Jómsvíkinga Drápur: Texts, Contexts and Intertexts .................................. 81 DANIEL SÄVBORG, Búi the Dragon: Some Intertexts of Jómsvíkinga Saga. 101 ALISON FINLAY, Comments on Daniel Sävborg’s Paper ............ 119 Jakub Morawiec, Danish Kings and the Foundation of Jómsborg ... 125 władysław duczko, Viking-Age Wolin (Wollin) in the Norse Context of the Southern Coast of the Baltic Sea ............... 143 MichaeL Lerche NieLseN, Runic Inscriptions Reflecting Linguistic Contacts between West Slav Lands and Southern -

Language Vitality and Transculturalization Of

DOI: https://doi.org/10.35520/diadorim.2020.v22n1a31999 Recebido em: 31 de janeiro de 2020 | Aceito em: 24 de abril de 2020 LANGUAGE VITALITY AND TRANSCULTURALIZATION OF EUROPEAN IMMIGRANT MINORITIES: POMERANIAN IN BRAZIL VITALIDADE LINGUÍSTICA E TRANSCULTURALIDADE DE MINORIAS DE IMIGRANTES: POMERANOS NO BRASIL Monica Maria Guimaraes Savedra1 Abstract This work presents part of the studies carried out on linguistic and cultural ethnicity of immigration languages in Brazil in the framework of a bilateral cooperation project between the Federal Fluminense University (UFF) and the Europa Universität-Viadrina (EUV). The discussion presented here is delimited to the context of Pomeranian immigration in the state of Espírito Santo, precisely in Santa Maria de Jetibá municipality. It aims to show the importance of linguistic and cultural vitality of the immigration variety to the pluri- and multilingual education proposals. This study sees Pomeranian as an autochthonous Brazilian language and it discusses linguistic policy actions that have been implemented to demonstrate the vitality of the immigration variety and the use of bi- plurilingualism with some other varieties in different fields and usage practices. From the results of an ethnographic research, we propose a Portuguese-Pomeranian bilingual literacy in the first grades, subsequently extended to other Germanic language(s) from the concept of intercomprehension. Keywords: Languages of immigration; neo-autochthony; multilingual teaching. Resumo Este trabalho apresenta parte dos estudos que foram desenvolvidos sobre etnicidade linguística e cultural de línguas de imigração no Brasil no âmbito de um projeto de cooperação bilateral entre a Universidade Federal Fluminense (UFF) e a Europa Universität-Viadrina (EUV). Delimitamos aqui a discussão ao contexto da imigração pomerana no Espírito Santo, mas exatamente ao município de Santa Maria de Jetibá, para mostrar a importância da vitalidade linguística e cultural da variedade de imigração para propostas de educação pluri- e multilíngue. -

European University VIADRINA

Online Publication of the European University VIADRINA Volume 1, Number 4 December 2013 dx.doi.org/10.11584/pragrev.2013.1.4 ISSN: 2196-2871 www.pragmatics-reviews.org PRAGMATICS.REVIEWS 2013.1.4 An important contribution to the research of the Pomeranian language in the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo Beate Höhmann. 2010. Sprachplanung und Spracherhalt innerhalb einer pommerischen Sprachgemeinschaft. Eine soziolinguistische Studie in Espírito Santo/Brasilien. Bern: Peter Lang Through the consideration of the Brazilian language policy and the language planning in the towns of Santa Maria de Jetibá, Alto Santa Maria and Caramuru in the state of in Espírito Santo, Beate Höhmann provides a complex picture of the current language use of the Pomeranian speech community and predicts the further development of the Pomeranian language in the examined area. The research aims to provide the newest results about the current language situation and about promoting Pomeranian language maintenance in Espírito Santo. This Pomeranian is already extinct in Pomerania - its country of origin - but it is still spoken by the descendants of farmers, who emigrated in the second half of the 19th Century to southern Brazil. The aim of the study is to analyse the factors that affect language preservation and language vitality in the investigated speech community. Moreover, language policy and language planning among the Pomeranians are further discussed. The empirical basis of the study consists of 263 questionnaires, interviews and participant observations in the studied speech community. However, the reference to the last two sources is made only implicitly. The main part of the study is the third chapter, which is dedicated to the factors of Pomeranian language maintenance. -

Uniwersytet Gdański University of Gdańsk

Uniwersytet Gdaski University of Gdask https://repozytorium.bg.ug.edu. pl Publikacja / The Empty Night ritual in the life of modern Kashubians, Publication Gustin Masa, Wyszogrodzka-Liberadzka Natalia Adres publikacji w Repozytorium URL / https://repozytorium.bg.ug.edu.pl/info/article/UOG71232c35c6df4880a3ad53df615a7735/ Publication address in Repository Data opublikowania w 4 sie 2021 Repozytorium / Deposited in Repository on Rodzaj licencji / Type Dozwolony uytek of licence Gustin Masa, Wyszogrodzka-Liberadzka Natalia: The Empty Night ritual in the life of Cytuj t wersj / modern Kashubians, Between the Worlds, Sofia: Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Cite this Studies with Ethnographic Museum Bulgarian Academy of Sciences; Paradigma, no. 2, version 2020, pp. 325-343 THE EMPTY NIGHT RITUAL IN THE LIFE OF MODERN KASHUBIANS Maša Guštin & Natalia Wyszogrodzka-Liberadzka Abstract: Empty Night (Pustô noc) is the Kashubian name for the ritual that takes place on the last night before the funeral of a deceased person when people gather in the dead man’s house to pray. After praying the rosary, they stay to chant special religious songs and watch over them until the morning. According to folk beliefs of the Kashubian region, the deceased stays permanently in the vicinity of his household until the funeral. When farewelled improperly, a person can return in the form of a demon/ghoul (wieszczi, òpi). Therefore, a prayer for the dead secures the peace of the living. The most common explanation for a modern man, who is not so keen on believing in supernatural/magical aspects of life, is that the repetition and monotony of singing bring relief to the participants of an Empty Night Ritual. -

Opportunity for the Operation of Natural Selection in a Contemporary Local Population (The Case of Slovincians, Poland)

Advances in Anthropology 2013. Vol.3, No.3, 121-126 Published Online August 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2013.33016 Opportunity for the Operation of Natural Selection in a Contemporary Local Population (The Case of Slovincians, Poland) Oskar Nowak1, Grażyna Liczbińska2*, Janusz Piontek1 1Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Faculty of Biology, Institute of Anthropology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland 2Department of Human Population Ecology, Faculty of Biology, Institute of Anthropology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland Email: [email protected], *[email protected] Received February 19th, 2013; revised March 19th, 2013; accepted March 29th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Oskar Nowak et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In research practice, it is possible to observe natural selection at work by analysing fertility and mortality. Crow’s index takes into account both of these vital statistics components and allows a quantitative esti- mation of the operation of natural selection on the basis of demographic birth and death figures. In this study, we use the classical Crow’s index to determine whether the disintegration of the Slovincian popu- lation in the second half of the 20th century was caused by factors of a biological nature, finally leading to disturbances in the reproductive strategy, or whether it was a result of the impact of many factors of a cultural nature. Use was made of measuring cards for 109 women and 38 men. -

0 Centro De Comunicação E Artes Programa De

0 CENTRO DE COMUNICAÇÃO E ARTES PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO STRICTO SENSU EM LETRAS – NÍVEL DE DOUTORADO EM LETRAS ÁREA DE CONCENTRAÇÃO: LINGUAGEM E SOCIEDADE NILSE DOCKHORN HITZ CRENÇAS LINGUÍSTICAS DE DESCENDENTES POMERANOS EM TRÊS LOCALIDADES PARANAENSES CASCAVEL- PR 2017 1 NILSE DOCKHORN HITZ CRENÇAS LINGUÍSTICAS DE DESCENDENTES POMERANOS EM TRÊS LOCALIDADES PARANAENSES Tese apresentada à Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná (UNIOESTE), para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Letras, junto ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Stricto Sensu em Letras, área de concentração em Linguagem e Sociedade. Linha de Pesquisa: Estudos da Linguagem: Descrição dos Fenômenos Linguísticos, Culturais, Discursivos e de Diversidade. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Vanderci de Andrade Aguilera Coorientadora: Profa. Dra. Aparecida Feola Sella. CASCAVEL – PR 2017 2 3 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço ao meu pai Erno Dockhorn (in memoriam) e à minha mãe Maria Giselda Glier Dockhorn, pela vida; A Deus, pela oportunidade de retornar aos estudos e de uma forma singela poder contribuir com a pesquisa da Universidade do Oeste do Paraná que é referência de ética, moral e compromisso com a formação dos profissionais da educação; À orientadora Professora Dra. Vanderci de Andrade Aguilera, que soube acolher e motivar o trabalho de pesquisa, sempre muito sábia, um belo exemplo de humanidade e criadora de paixões, grata Mestra! À coorientadora, Professora Dra. Maria Aparecida Feolla, que fez a indicação temática deste estudo e as correções criteriosas, próprias de uma grande pesquisadora! Às Professoras Dra. Loremi Loregian Penkal; Dra. Fabiane Cristina Altino; Dra. Sanimar Busse; Dra. Maria Elena Pires Santos e Esther Gomes de Oliveira, meus agradecimentos pelas valiosas contribuições, exemplos de quando há dedicação, é possível vencer! Aos entrevistados pomeranos, que, surpreendidos pelo interesse do outro, perguntavam: “Mas que isso interessa a você?”. -

Call for Papers

15th International Conference on Diagnostics of Processes and Systems 5 - 7 September 2022, Kashubia, Poland Important dates Call for papers 25th of March 2022 Full-length Paper Submission Deadline The 15th Interna�onal Conference on Diagnos�cs of Processes and Systems (DPS), hosted by the Gdańsk 25th of March 2022 University of Technology, will be held in Kashubia (Pomerania, Poland), on September 5-7, 2022. Invited and Special Sessions Proposals Conference history and motivation 1st May 2022 Paper Acceptance In the last few decades, the diagnos�cs of processes and systems has developed significantly both in theory and in Notification prac�ce. Both the scope and applica�ons of technical diagnos�cs cover many well-established topics, and 15th May 2022 numerous emerging advances in the fields of control and systems engineering, robo�cs and mechatronics, aerospace, applied mathema�cs, ar�ficial intelligence, decision support, sta�s�cs and signal processing. More and Final Paper Submission more effec�ve methods of fault diagnosis and their various applica�ons are considered in the classical areas of 20th May 2022 electrical, mechanical, medical and chemical as well as in inter-sort or completely new fields of human ac�vity. Early Registration Deadline These methods are of key importance for the early iden�fica�on of emerging failures and ensuring the safe, 30th June 2022 economic and ecological opera�on of machines, devices and systems. In the field of automa�on and robo�cs, Regular Registration special a�en�on is paid to fault-tolerant control, which combines diagnos�cs with control methods to deal with Deadline faults intelligently and efficiently, thus reducing the risk to the safety of systems. -

Newsletter Summer 2003

Max Kade Institute Friends Newsletter VOLUME 12 NUMBER 2 • SUMMER 2003 UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON, 901 UNIVERSITY BAY DR., MADISON, WI 53705 The magnificent two-story 1882 WHAT’S INSIDE: Turner Hall ballroom (left) MKI Friends Profile: was recently Don Zamzow. restored to its original splendor Page 4 (below) and public function Director’s Corner. as a venue for Page 5 civic and cultural events. New Feature! “Speaking of Language.” Pages 6–7 Turners Friends celebrate Annual Dinner story and 150 years photo By Rose Marie Barber gallery. Pages 8-9 The Milwaukee Turners, Inc., and the Milwaukee Photos courtesy of the Milwaukee Turners Book Review by Cora Lee Turners School of Gymnastics th Kluge. will be celebrating their 150 Page 10 anniversary on September 6, 2003. Past presidents Time: 6 p.m. cocktails and forty-year members will be honored. There will 6:45 p.m. dinner be zither music during cocktails, and dinner in the 8 p.m. speakers and Highlights of recent library entertainment acquisitions. ballroom followed by brief histories of the Turners, an Page 11 exhibition, in full 1853 costume, by our ladies class, Date: September 6, ethnic dancing by the Oberlandlers; and a sing-along 2003 of familiar German and American songs. Collection Place: Turners Hall, The Milwaukee Turners, known originally as the 1034 Old World Feature: Socialer Turnverein, was founded on July 17, 1853, Third Street, Legal Milwaukee advice in Phillips Tavern on Market Square, a popular books. gathering place of the time. These pioneers were For cost and more educators, lawyers, doctors, entrepreneurs, and info call 414-272- Pages 1733 14–15 intellectuals who had lost a revolution in 1848 and came to America to realize their dream of freedom.