Language Vitality and Transculturalization Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Contact in Pomerania: the Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian

P a g e | 1 Language Contact in Pomerania: The Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian Nick Znajkowski, New York University Purpose The effects of language contact and language shift are well documented. Lexical items and phonological features are very easily transferred from one language to another and once transferred, rather easily documented. Syntactic features can be less so in both respects, but shifts obviously do occur. The various qualities of these shifts, such as whether they are calques, extensions of a structure present in the modifying language, or the collapsing of some structure in favor the apparent simplicity found in analogous foreign structures, all are indicative of the intensity and the duration of the contact. Additionally, and perhaps this is the most interesting aspect of language shift, they show what is possible in the evolution of language over time, but also what individual speakers in a single generation are capable of concocting. This paper seeks to explore an extremely fascinating and long-standing language contact situation that persists to this day in Northern Poland—that of the Kashubian language with its dominating neighbors: Polish and German. The Kashubians are a Slavic minority group who have historically occupied the area in Northern Poland known today as Pomerania, bordering the Baltic Sea. Their language, Kashubian, is a member of the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages and further belongs to the Pomeranian branch of Lechitic languages, which includes Polish, Silesian, and the extinct Polabian and Slovincian. The situation to be found among the Kashubian people, a people at one point variably bi-, or as is sometimes the case among older folk, even trilingual in Kashubian, P a g e | 2 Polish, and German is a particularly exciting one because of the current vitality of the Kashubian minority culture. -

Justice Under Pressure – Repressions As a Means of Attempting to Take Control Over the Judiciary and the Prosecution in Poland

IUSTITIA RAPORTY Justice under pressure – repressions as a means of attempting to take control over the judiciary and the prosecution in Poland. Years 2015–2019 Edited by Jakub Kościerzyński Prepared by: sędzia SA Michał Bober sędzia SO Piotr Gąciarek sędzia SR Joanna Jurkiewicz sędzia SR Jakub Kościerzyński prokurator PR Mariusz Krasoń sędzia SR Dorota Zabłudowska Th e report was drawn up by judges from the Polish Judges’ Association “Iustitia” and by a prosecutor from the “Lex Super Omnia” Association of Prosecutors. “Iustitia” is the largest association of judges in Poland. It is fully independent, apolitical and self-governing, with over 3500 members, which is over 1/3 of the total number of judges. Our main mission is to defend the principles of a democratic state of law: freedom, rights and civil liberties, which are the cornerstone of democratic Poland. We are active in many fi elds not only throughout Poland but also in the international arena as a member of international associations of judges (IAJ, EAJ, MEDEL). “Lex Super Omnia” is fully independent, apolitical and self-governing. It brings together more than 200 prosecutors. Th e main goal of the association is to strive for establishing an independent prosecution, the position of which is defi ned in the Polish Constitution. ISBN: 978-83-920641-8-3 Spis treści Introduction ................................................................................................................. 7 Part I. Judges ............................................................................................................... 9 Chapter I. List of judges against whom the disciplinary prosecutor of common courts, judge Piotr Schab and his deputies, judges: Michał Lasota and Przemysław W. Radzik, have launched investigations or initiated disciplinary proceedings in connection with judicial and extrajudicial activities. -

Private Car “The Kashubian's Region” Tour with Museum from Hotel & Also

Private car “The Kashubian’s Region” tour with Museum from hotel & also includes private car return airport transfers (2 Sharing) - £55pp Private Tour Includes: Return private car airport transfers Private Tour Guide with extensive knowledge of the area. Tour in the Kashubian’s Region. Entry to biggest open air museum for 2 Adults. Visit to Kashubian Centre. Dinner in local restaurant -Optional (extra charges apply). Tour Guide: Mr. Jacek Waldoch Features: About me: I am passionate about Gdansk & its history & Tour in English surroundings. I am professional guide with a certificate from Flexible time. Stutthof Museum. Museum ticket & parking fares included. Information about local cuisines & recommendations. Pick up & return to Hotel directly with private car. Includes return private car transfers to airport (normally costs £25 pp) Duration (approx.): 5 Hours – 6 Hours. Friendly atmosphere. Ceramics has a centuries-old tradition in Kashubia, and again the designs are simple. Kashubian ceramics are decorated with a number of traditional designs including the Kashubian star, fish scales and local flowers, all embellished with wavy lines and dots. The Kashubians are also great weavers, even managing to weave buckets and jugs from pine roots and straw capable of holding water. Their weaving skills can also be seen on the roofs of the many thatched houses in the region. The Kashubians are also well known for a style of primitive painting on glass, woodcuts, and wooden sculptures including roadside chapels known as the Passions of Christ. Wood is also carved into elaborate walking sticks, animal heads and musical instruments, including the extraordinary burczybas, similar to a double bass but in the shape of a barrel with a horse hair tail. -

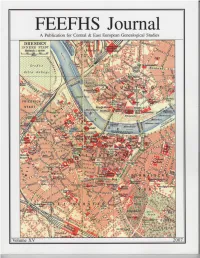

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

Regional Investment Attractiveness 2014

Warsaw School of Economics REGIONAL INVESTMENT ATTRACTIVENESS 2014 Western Pomeranian Voivodship Hanna Godlewska-Majkowska, Ph.D., Associate Professor at the Warsaw School of Economics Agnieszka Komor, Ph.D. 3DWU\FMXV]=DUĊEVNL3K' Mariusz Czernecki, M.A. Magdalena Typa, M.A. Report prepared for the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency at the Institute of Enterprise, Warsaw School of Economics Warsaw, December 2014 2014 Regional investment attractiveness 2014 Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency (PAIiIZ) is a governmental institution and has been servicing investors since 1992. Its mission is to create a positive image of Poland in the world and increase the inflow of foreign direct investments by encouraging international companies to invest in Poland. PAIiIZ is a useful partner for foreign entrepreneurs entering the Polish market. The Agency guides investors through all the essential administrative and legal procedures that involve a project. It also provides rapid access to complex information relating to legal and business matters regarding investments. Moreover, it helps in finding the appropriate partners and suppliers together with new locations. PAIiIZ provides free of charge professional advisory services for investors, including: investment site selection in Poland, tailor-made investors visits to Poland, information on legal and economic environment, information on available investment incentives, facilitating contacts with central and local authorities, identification of suppliers and contractors, care of existing investors (support of reinvestments in Poland). Besides the OECD National Contact Point, PAIiIZ also maintains an Information Point for companies ZKLFK DUH LQWHUHVWHG LQ (XURSHDQ )XQGV $OO RI WKH $JHQF\¶V DFWLYLWLHV DUH VXSSRUWHG E\ WKH Regional Investor Assistance Centres. Thanks to the training and ongoing support of the Agency, the Centres provide complex professional services for investors at voivodship level. -

The Prehistory of Polish Pomerania

THE BALTIC POCKET LIBRARY THE PREHISTORY OF POLISH POMERANIA BY DR. JÓZEF KOSTRZEWSKI PROFESSOR OF PREHISTORY*^!' THE UNIVERSITY OF POZNAŃ 1 9 TORUŃ (POLAND)3_6 PUBLISHED BY THE BALTIC INSTITUTE J. S. BERGSON, 4, VERNON PLACE, LONDON W. C. 1 THE PREHISTORY OF POLISH POMERANIA r Double face urn and bronze cauldron of provincial workmanship, found at Topolno, district of Świecie. I 4 Ki THE BALTIC POCKET LIBRARY THE PREHISTORY OF POLISH POMERANIA BY DR. JÓZEF KOSTRZEWSKI PROFESSOR OF PREHISTORY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF POZNAŃ 19 TORUŃ (POLAND) 3 6 PUBLISHED BY THE BALTIC INSTITUTE J. S. BERGSON, 4, VERNON PLACE, LONDON W. C, 1 Printed in Poland by “Rolnicza Drukarnia i Księgarnia Nakładowa Poznań, Sew. Mielżyńskiego 24 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1. THE STONE AGE......................................................... 9 The Final Palaeolithic Period, p. 9. The Mesolithic Age, p. 10. The Neolithic Age, p. 13; Ribbon Ware, p. 14; Funnel Cup Culture, p. 16; Eastern Globular Amphora Culture, p. 19; The Corded Pottery Culture, p. 21; The Rzucewo Culture, p. 24; The Comb Pottery, p. 29; Finds of Copper, p. 30. CHAPTER 2. THE BRONZE AGE....................................................32 The Early Bronze Age, p. 32; The Iwno Culture, p. 33; Hoards, p. 34. The Second Bronze Age Period, p. 36. The Third Bronze Age Period, p. 37; The Cassubian Local Group, p. 38; The Chełmno Local Group, p. 40; Affinities of the Lusatian Culture, p. 41. The Fourth Bronze Age Period, p. 43; The Cassubian Sub-Group, p. 43,; The Chełmno Sub-Groun, p. 46. The Fifth (Latest) Bronze Age Period, p. 49; The Cassubian Sub-Group, p. -

Scripta Islandica 65/2014

SCRIPTA ISLANDICA ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 65/2014 REDIGERAD AV LASSE MÅRTENSSON OCH VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON GÄSTREDAKTÖRER JONATHAN ADAMS ALEXANDRA PETRULEVICH HENRIK WILLIAMS under medverkan av Pernille Hermann (Århus) Else Mundal (Bergen) Guðrún Nordal (Reykjavík) Heimir Pálsson (Uppsala) UPPSALA, SVERIGE Publicerad med stöd från Vetenskapsrådet. © Författarna och Scripta Islandica 2014 ISSN 0582-3234 Sättning: Ord och sats Marco Bianchi urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-235580 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-235580 Contents Preface ................................................. 5 ÞÓRDÍS EDDA JÓHANNESDÓTTIR & VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON, The Manu- scripts of Jómsvíkinga Saga: A Survey ...................... 9 Workshop Articles SIRPA AALTO, Jómsvíkinga Saga as a Part of Old Norse Historiog - raphy ................................................ 33 Leszek P. słuPecki, Comments on Sirpa Aalto’s Paper ........... 59 ALISON FINLAY, Jómsvíkinga Saga and Genre ................... 63 Judith Jesch, Jómsvíkinga Sǫgur and Jómsvíkinga Drápur: Texts, Contexts and Intertexts .................................. 81 DANIEL SÄVBORG, Búi the Dragon: Some Intertexts of Jómsvíkinga Saga. 101 ALISON FINLAY, Comments on Daniel Sävborg’s Paper ............ 119 Jakub Morawiec, Danish Kings and the Foundation of Jómsborg ... 125 władysław duczko, Viking-Age Wolin (Wollin) in the Norse Context of the Southern Coast of the Baltic Sea ............... 143 MichaeL Lerche NieLseN, Runic Inscriptions Reflecting Linguistic Contacts between West Slav Lands and Southern -

On 23 October 1815, Sweden Lost Its Last Remaining Conquest Of

Swedish Pomeranian Shipping in the Revolutionary Age (1776–1815) Magnus Ressel n 23 October 1815, Sweden lost its last remaining conquest of the OThirty Years War. As a result of a complicated exchange, Sweden gai- ned Norway as a kingdom to be ruled in personal union by its king. In return, Denmark obtained the little Duchy of Lauenburg, which Prussia had acquired previously from Hanover in exchange for Eastern Frisia, only to be used as a bargaining chip. To make up for differences in the relative importance of these territories, substantial flows of money accompanied the entire clearing pro- cess.1 Swedish Pomerania thus left the Swedish orbit for good. It had been a small province on the southern coast of the Baltic with an area of 4 400 km², the main part stretching from Damgarten to Anklam with Stralsund and Gre- ifswald as the most important cities. The island of Rügen (with another 920 km²) had also belonged to the Swedish possessions in the Holy Roman Em- pire, as had the city of Wismar with a little hinterland (this only until 1803). Magnus Ressel (fil.dr) arbetar som forskare vid universitetet i Bochum. Han skrev sin avhandling på ämnet ”Northern Europe and the Barbary corsairs during the Early Modern Epoch”. Han bedriver för tillfället forskning rörande Hansan, Nederländerna, Danmark och Sverige under Trettioåriga kriget. 64 65 Sweden’s provinces in Germany had been saved twice for the kingdom, in 1678 by France alone and in 1719 by France and England together when they had joined to preserve as much as possible of the weakened country’s German territories.2 Now this was undone forever. -

The Kaschuben

The Kaschuben Source: Deutscher Volkskalender für Bessarabien – 1931 Tarutino Press and Printed by Deutschen Zeitung Bessarabiens Pages 111-114 Translated by: Allen E. Konrad April, 2014 Internet Location: urn:nbn:de:bvb:355-ubr13934-5 When translating a document that contains proper names, I am never sure which direction to go. Keep the original name, or make it more Anglicized. In the following translation, I have done both because sometimes it seemed to be significant to stay with the original, while at other times nothing seemed to be lost in Anglicizing it. I have no information as to who author F. St. was. I browsed the whole 1931 Calendar and did not come across any other mention of a person that would fit the F. St. signature. ================================================================ [Translation Begins] The Kassuben Historical Study by F. St. All Swabian people in Bessarabia call those who speak the Low German (plattdeutsch) language, Kashuben (Kassuben). Today, our Swabian and Plattdeutsch folks peacefully live in full harmony next to and with each other, the later primarily in purchased land of daughter communities, hundreds of Plattdeutsch folks have cheerfully taken Swabians to be their wives and many a Swabian has chosen a smart Kashuban woman to be his companion. And they do not regret it. If they were to be free and had to marry again, they would probably do it once again. —It was not always like that. Swabian and Kashuban folks were only too glad and eager to tease, mock, make a fool of, josh, and irritate one another whenever they came together, for example, at a place of business, or a tavern, at the market, at a wedding, or at the occasion of some special festival; during military recruitment, etc. -

A Tribe After All? the Problem of Slovincians' Identity in An

M. Filip. A Tribe after all? ... УДК 572; ББК 28.71; DOI https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu19.2018.208 M. Filip A TRIBE AFTER ALL? THE PROBLEM OF SLOVINCIANS’ IDENTITY IN AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH 1 The identity of Slovincians is a subject of a wide range of controversies in the field of Disputatio / Дискуссия Slavic studies. The root of the conflict between supporters of the ethnic distinctiveness of Slovincians, and opponents who suggest Slovincians are a part of the Kashubian ethnic group (and thus an ethnographic group), is the past work of Aleksandr Hilferding2, a Russian linguist and ethnographer who was the first to describe this group’s history and culture. He claimed that Slovincians and Kashubians were the last Slavs on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea to oppose Germanisation since early medieval. Hilferding’s theses were the basis of the canonical history of Slovincians, in which this ethnic group had roots to a tribe of the same name. In the middle of the 19th century, Slovincians living between Lake Gardno and Lake Łebsko were indeed the westernmost group of Slavs living in Pomerania, or more precisely on the eastern frontier of western Pomerania (ger. Hinterpommern). They commonly switched to the German language and assimilated a German ethnic identity as late as the start of the 20th century. As a consequence, Slovincians who found themselves living in Poland after World War II were seen as Germans and were subjected to displacement by settlers and administrators of the region. The Polish intellectual elite, however, did not forget about the Slavic origin of the region’s inhabitants and demanded leaving them on the Polish soil and suggested their re-Slavisation, or de facto Polonisation. -

Centralantikvariatet Catalogue 80 Pommern

CENTRALANTIKVARIATET catalogue 80 POMMERN Books from and about Pomerania, from the library of Victor von Stedingk Introduction by Lars Victor von Stedingk Stockholm mmxv centralantikvariatet Österlånggatan 53 | 111 31 Stockholm | +46 8 411 91 36 www.centralantikvariatet.se | e-mail: [email protected] Bankgiro 585-2389 Medlem i Svenska antikvariatföreningen Member of ILAB Förord För 200 år sedan, i oktober 1815, lämnade de sista svenska soldaterna och ämbets- männen Svenska Pommern, som då i ungefär 170 år varit en svensk provins. Istället blev det en del av Preussen. Detta 200-årsjubileum har väl inte uppmärksammats nämnvärt i Sverige, men vi tycker det är mycket roligt att just detta år kunna pre- sentera en katalog med böcker om och från Pommern. Böckerna i samlingen har tillhört Victor von Stedingk, boksamlare och bok- bandsspecialist, som på grund av släktens pommerska ursprung hade en stark för- kärlek för böcker rörande Pommern, och då inte bara det Svenska Pommern utan lika mycket det forna hertigdömet Pommern. Om familjen von Stedingk och Pom- mern berättar Lars Victor von Stedingk i sin inledning till katalogen. Urvalet av böcker i samlingen är mycket personligt och deras olikartade kopp- lingar till Pommern ger en stor variation på både ämnen och ålder. Påpekas bör mängden av tidiga Pommerntryck, med många tryckorter och tryckare represen- terade. Åtskilliga av dessa är också i mycket fina samtida band, ofta även de med associationer till Pommern, och i några fall med utsökta provenienser, som t.ex. det hertigliga biblioteket i Stettin, nuvarande Szczecin i Polen. Ett särskilt register över pommerska tryckare och tryckorter återfinns sist i katalogen. -

European University VIADRINA

Online Publication of the European University VIADRINA Volume 1, Number 4 December 2013 dx.doi.org/10.11584/pragrev.2013.1.4 ISSN: 2196-2871 www.pragmatics-reviews.org PRAGMATICS.REVIEWS 2013.1.4 An important contribution to the research of the Pomeranian language in the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo Beate Höhmann. 2010. Sprachplanung und Spracherhalt innerhalb einer pommerischen Sprachgemeinschaft. Eine soziolinguistische Studie in Espírito Santo/Brasilien. Bern: Peter Lang Through the consideration of the Brazilian language policy and the language planning in the towns of Santa Maria de Jetibá, Alto Santa Maria and Caramuru in the state of in Espírito Santo, Beate Höhmann provides a complex picture of the current language use of the Pomeranian speech community and predicts the further development of the Pomeranian language in the examined area. The research aims to provide the newest results about the current language situation and about promoting Pomeranian language maintenance in Espírito Santo. This Pomeranian is already extinct in Pomerania - its country of origin - but it is still spoken by the descendants of farmers, who emigrated in the second half of the 19th Century to southern Brazil. The aim of the study is to analyse the factors that affect language preservation and language vitality in the investigated speech community. Moreover, language policy and language planning among the Pomeranians are further discussed. The empirical basis of the study consists of 263 questionnaires, interviews and participant observations in the studied speech community. However, the reference to the last two sources is made only implicitly. The main part of the study is the third chapter, which is dedicated to the factors of Pomeranian language maintenance.