Constitutional Issues Relating to Jury Trials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1887 Constitution of Hawaii ARTICLE 13. the Government Is Conducted

1887 Constitution of Hawaii ARTICLE 13. The Government is conducted for the common good, and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men. ARTICLE 20. The Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct. ARTICLE 21. The Government of this Kingdom is that of a Constitutional Monarchy, under His Majesty Kalakaua, His Heirs and Successors. ARTICLE 22. The Crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kalakaua, and to the Heirs of His body lawfully begotten, and to their lawful Descendants in a direct line; failing whom, the Crown shall descend to Her Royal Highness the Princess Liliuokalani, and the heirs of her body, lawfully begotten, and their lawful descendants in direct a line. ARTICLE 24. His Majesty Kalakaua, will, and his Successors shall take the following oath: I solemnly swear in the presence of Almighty God, to maintain the Constitution of the Kingdom whole and inviolate, and to govern in conformity therewith. ARTICLE 41. The Cabinet shall consist of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Finance, and the Attorney General, and they shall be His Majesty's special advisors in the executive affairs of the Kingdom; and they shall be ex-officio members of His Majesty's Privy Council of State. They shall be appointed and commissioned by the King and shall be removed by him, only upon a vote of want of confidence passed by a majority of all the elective members of the Legislature or upon conviction of felony, and shall be subject to impeachment. -

Hawaiians Should Be Portrayed in Popular Media

‘Okakopa (October) 2018 | Vol. 35, No. 10 THE LIVING WATER OF OHA www.oha.org/kwo ‘THE ING’ page K 12 ‘The The announcement of an upcoming movie about Kamehameha I opens discussion on how Hawaiians should be portrayed in popular media. INSIDE 2018 General election Guide - Photo: Nelson Gaspar Kıng’ $REAMINGOF THEFUTURE Hāloalaunuiakea Early Learning Center is a place where keiki love to go to school. It‘s also a safe place where staff feel good about helping their students to learn and prepare for a bright future. The center is run by Native Hawaiian U‘ilani Corr-Yorkman. U‘ilani wasn‘t always a business owner. She actually taught at DOE for 8 years. A Mālama Loan from OHA helped make her dream of owning her own preschool a reality. The low-interest loan allowed U‘ilani to buy fencing for the property, playground equipment, furniture, books…everything needed to open the doors of her business. U‘ilani and her staff serve the community in ‘Ele‘ele, Kaua‘i, and have become so popular that they have a waiting list. OHA is proud to support Native Hawaiian entrepreneurs in the pursuit of their business dreams. OHA‘s staff provide Native Hawaiian borrowers with personalized support and provide technical assistance to encourage the growth of Native Hawaiian businesses. Experience the OHA Loans difference. Call (808) 594-1924 or visit www.oha.org/ loans to learn how a loan from OHA can help grow your business. -A LAMA,OANS CANMAKEYOURDREAMSCOMETRUE (808) 594-1924 www.oha.org/loans follow us: /oha_hawaii | /oha_hawaii | fan us: /officeofhawaiianaffairs | Watch us: /OHAHawaii ‘okakopa2018 3 ‘o¯lelo a ka luna Ho‘okele messagE from the ceo bEing an informED votEr is your kulEana Aloha mai ka¯kou, istration. -

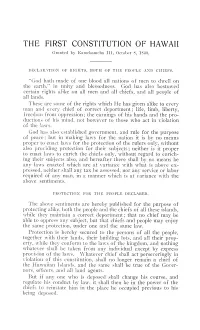

1840 Constitution

THE FIRST CONSTITUTION OF HAWAII Granted by Kamehameha III, October 8, 1840. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS, BOTH OF THE PEOPLE AND CHIEFS. "God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on the earth," in unity and blessedness. God has also bestowed certain rights alike on all men and all chiefs, and all people of all lands. These are some of the rights which He has given alike to every man and every chief of correct deportment; life, limb, liberty, freedom from oppression; the earnings of his hands and the pro- ductions of his mind, not however to those who act in violation of the laws. God has also established government, and rule for the purpose of peace ; but in making laws for the nation it is by no means proper to enact laws for the protection of the rulers only, without also providing protection for their subjects; neither is it proper to enact laws to enrich the chiefs only, without regard to enrich- ing their subjects also, and hereafter there shall by no means be any laws enacted which are at variance with what is above ex- pressed, neither shall any tax be assessed, nor any service or labor required of any man, in a manner which is at variance with the above sentiments. PROTECTION FOR THE PEOPLE DECLARED. The above sentiments are hereby published for the purpose of protecting alike, both the people and the chiefs of all these islands, while they maintain a correct deportment; that no chief may be able to oppress any subject, but that chiefs and people may enjoy the same protection, under one and the same law. -

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources Materials Available at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Libraries Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Lori Kidani 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS CALL NUMBER LOCATIONS.....................................................................................................1 BIBLIOGRAPHIES......................................................................................................................2 CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE AND PROPERTY ............................................................................3 LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES.........................................................................................5 LAWS, CURRENT ......................................................................................................................9 LAWS, HISTORICAL ................................................................................................................10 LEGAL CASES .........................................................................................................................18 NATIVE RIGHTS AND CLAIMS................................................................................................20 OVERTHROW AND ANNEXATION..........................................................................................23 REFERENCE MATERIALS.......................................................................................................26 SOVEREIGNTY AND SELF DETERMINATION........................................................................27 -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

The Color of Nationality: Continuities and Discontinuities of Citizenship in Hawaiʻi

The Color of Nationality: Continuities and Discontinuities of Citizenship in Hawaiʻi A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 2014 By WILLY DANIEL KAIPO KAUAI Dissertation Committee: Neal Milner, Chairperson David Keanu Sai Deborah Halbert Charles Lawrence III Melody MacKenzie Puakea Nogelmeier Copyright ii iii Acknowledgements The year before I began my doctoral program there were less than fifty PhD holders in the world that were of aboriginal Hawaiian descent. At the time I didn’t realize the ramifications of such a grimacing statistic in part because I really didn’t understand what a PhD was. None of my family members held such a degree, and I didn’t know any PhD’s while I was growing up. The only doctors I knew were the ones that you go to when you were sick. I learned much later that the “Ph” in “PhD” referred to “philosophy,” which in Greek means “Love of Wisdom.” The Hawaiian equivalent of which, could be “aloha naʻauao.” While many of my family members were not PhD’s in the Greek sense, many of them were experts in the Hawaiian sense. I never had the opportunity to grow up next to a loko iʻa, or a lo’i, but I did grow up amidst paniolo, who knew as much about makai as they did mauka. Their deep knowledge and aloha for their wahi pana represented an unparalleled intellectual capacity for understanding the interdependency between land and life. -

State of Hawaii 2001 Reapportionment Commission Final Report and Reapportionment Plan Submitted to the Twenty-First Legislature

State of Hawaii 2001 Reapportionment Commission Final Report and Reapportionment Plan Submitted to The Twenty-First Legislature Regular Session 2002 Submitted by: Office of Elections L rL STATE OF HAWAII 2001 REAPPORTIONMENT PROJECT State Capitol, Room 411 Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Wayne K. Minami Chair The Honorable Robert Bunda, President and Members of the Senate Jill E. Frierson Vice-Chair The Honorable Calvin K.Y. Say, Speaker and Members of the House of Representatives Deron K. Akiona Twenty-first State Legislature Lori J. G. Hoo State Capitol Shelton G. W. Jim On Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Lynn C. Kinney Dear Sirs and Mesdames: Kenneth T. G. Lum Harold S. Masumoto The 2001 Reapportionment Commission submits the final Reapportionment Commission Report pursuant to Article III, Section 4, Hawaii State Constitution, and DavidW. Rae section 25-2, Hawaii Revised Statutes. This report addresses the plans adopted by the Commission to govern the election of the members of the next five succeeding legislatures of the State of Hawaii and also elections of the representatives of the State of Hawaii to the United States House of Representatives for the next five succeeding congresses commencing with the election of 2002. The report discusses the work done by the Commission and offers recommendations for future reapportionments. Sincerely, K. MINAMI, Chairperson E. FRIERSON, Vice-Chairperson DERON K. AKIONA ~GJtiL. L~ SHELTONG.W. JIMONc1~L --4'- - ~.I . \. -!~~ --.,__,,-n·'~~ ~~ NNETHT.~. L~~ ~·k~ David ~J. Rae ** HAROLD S. MASUMOTO DAVIDW.RAE ** Mr. Rae approved the final report but was not available for signature prior to printing. L I I,_ r- 1 r L l f STATE OF HAWAII 2001 REAPPORTIONMENT COMMISSION FINAL REPORT AND REAPPORTIONMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Membership of the Commission and the Advisory Councils . -

Congressional Record-House. April 4

·. • 3746 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. APRIL 4, Company E, Eleventh Regiment Indiana Volunteer Infantry, and poses to place on the pension roll the name of John B. Fairchilcl, to pay him a pension of $50 per month in lieu of that he is now· late of Company C, One hundred and twenty-third Regiment Ohio recei vi n O'. Volunteer Infantry, and to pay him a pension of $24 per month in The bill was reported to the Senate without amendment, ordered lieu of that he is now receiving. to a third reading, read the third time, and passed. 'I'he bill was reported to the Senate without amendment, ordered EMMA B. REED, to a third reading, read the third time, and passed. The bill (H. R. 744.5) granting a pension to Emma B. Reed JOHN C. RAY. was considered -as in Committee of the Whole. It proposes to The bill (H. R. 7488) granting a pension to John C. Ray was place on the pension roll the name of Emma B. Reed, the per considered as in. Committee of the Whole. It proposes to place manently helple s daughter of Edgar C. Reed, late of Company I, on the pens.ion roll the name of John C. Ray, late pilot of the One hundred and twenty-second Regiment Pennsylvania Volun U. S. steamers Champion and Sp1'ingfield, and to pay him a pen- teer Infantry and to pay her a pension of $12 per month, such ~ion of $.24 per month. · pension to be paid to the duly constituted guardian or trustee of The bill was reported to the Senate without amendment, ordered such child. -

THE PROCESS and OUTCOMES of the 2010 CONSTITUTONAL REFORM in TONGA a Study of the Devolution of Executive Authority from Monarc

THE PROCESS AND OUTCOMES OF THE 2010 CONSTITUTONAL REFORM IN TONGA A Study of the Devolution of Executive Authority from Monarchy to Representative Government in a Polynesian Society Mele Ikatonga Selisa Tupou ‘aka’ Mele Tupou Vaitohi LLB; LLM. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Otago in 2019 Faculty of Law ABSTRACT Supervisory Committee: Professor Andrew Geddis Faculty of Law Professor Jacinta Ruru Faculty of Law Mr Marcelo Rodriguez Ferrere Faculty of Law Ko e foaki ʻo e Konisitutone ʻo Tongá ʻi he 1875, ne hoko ia ko e maka maile ki he hisitōlia ʻo e tukuʻau mai e laó mo e fakalakalaka ʻa Tongá ʻi he ngāue ʻaufuatō ʻa e Tuʻí ko Tupou I. Naʻe hanga ʻe he Konisitutoné ʻo vahevahe e kakai ʻo e fonuá ki he ngaahi faʻunga e tolu – ko e laine faka-Tuʻí; ko e houʻeiki nōpelé pe maʻu tofiʻa e 30; pea mo e kakaí. Naʻe lava peʻe he Konisitutoné, ʻa ia ne tongi pea mei he nofo ʻa kaingá, ke ne pukepuke ʻa Tonga he ngaahi taʻu lahi – ka ʻi heʻene aʻu mai ki he ʻahó ni, kuo liliu. ʻI Nōvema ʻo e 2010, ne hoko ai ha fakalelei faka-konisitutone mo faka- politikale peá ne hoko ai ke fakaʻatā ‘e he Tuʻí ha ʻepoki foʻou mo ha hala fononga foʻou ke fou atu ai ʻa Tonga. Naʻe mokoi ʻa e Tama Tuʻí ke momoi ʻa e konga lahi ʻo hono mafai pulé ki he kau Minisitá ʻo e Kapinetí, ʻa ia ne fili ʻe he Palēmiá pea mei Fale Alea, ka ʻoku maʻu ai e tokolahi ʻe he kau fakafofonga ʻo e kakaí. -

© 2016 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works. 1

LAW, NARRATIVE, AND THE CONTINUING COLONIALIST..., 16 Temp. Pol. & Civ.... 16 Temp. Pol. & Civ. Rts. L. Rev. 1 Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review Fall 2006 Articles LAW, NARRATIVE, AND THE CONTINUING COLONIALIST OPPRESSION OF NATIVE HAWAIIANS David Barnarda1 Copyright (c) 2006 Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review; David Barnard Abstract The article does three things. First, and for the first time, it brings to bear the perspectives of critical race theory, postcolonial theory, and narrative theory on the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2000 decision in Rice v. Cayetano, which dealt a severe blow to Native Hawaiians’ struggles for redress and reparations for a century of dispossession and impoverishment at the hands of the United States. Second, it demonstrates in the concrete case of Hawaii the power of a particular historical narrative--when it is accepted uncritically by the Supreme Court--to render the law itself into an instrument of colonial domination. Third, it links important postcolonial writers--Edward Said, Albert Memmi, and Ngugi wa Thiong’o--to contemporary discourse in critical race theory and the narrative aspects of law. The history of the Hawaiian Islands is a far cry from the idyllic, palm fringed beaches of the travel posters. It is a story of domination and dispossession of an indigenous society. The article shows how Western historians have tried to erase this story, and put in its place a story of the civilizing influences of Western missionaries and traders, who brought modern technology and democratic government to a primitive people. This story played a pivotal role in the Rice opinion, enabling the Supreme Court to ignore and evade the U.S. -

Amanda Pacheco Comparative History of Ideas Senior Thesis December, 2005

Past, Present, and Politics: A Look at the Native Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement By: Amanda Pacheco Comparative History of Ideas Senior Thesis December, 2005 Table of Contents: Introduction: Ea 1 Chapter One: Ku Kanaka 7 -What is the native Hawaiian sovereignty movement? 8 -What tools is the movement using to achieve sovereignty? 12 Chapter Two: Imua e na poki’i 17 -Ka Lahui Hawaii 19 -The Nation State of Hawaii 24 -The Hawaiian Kingdom Government 28 Chapter Three: Onipa’a kakou 35 -Practicality and Feasibility 37 -Probability 46 -What faces the sovereignty initiative as a whole? 52 Conclusion: Kuna’e 56 Endnotes 62 Resource List 68 1 Introduction: Ea The Ruins To choose the late noon sun, running barefoot on wet Waimanalo beach; to go with all our souls’ lost yearnings to that deeper place where love has let the stars come down and my hair, shawled over bare shoulders, falls in black waves across my face; there, at last, escaped from the ruins of our nation, to lift our voices over the sea in bitter songs of mourning. - Haunani-Kay Trask1 2 Like many other words in the native Hawaiian language, the term “Ea”2 has several meanings that are dear to the hearts of those sympathetic to the native Hawaiian fight for self-determination: it means sovereignty, rule, independence; life, breath, vapor, air, spirit; it can also mean to rise up.3 This term has been used by several native Hawaiian sovereignty groups in the past in regards to the movement, and I chose it as a beginning to this thesis, which will critically analyze and critique the current sovereignty movement. -

COMMITTEE of the WHOLE MINUTES C��N��L �F Th� C��Nt� �F M�

COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE Cnl f th Cnt f M MINUTES br 2, 200 Cnl Chbr, 8th lr COEE: 9:01 a.m. ESE: Councilmember Michael J. Molina, Chair Councilmember Danny A. Mateo, Vice-Chair (In :02 .. Councilmember Gladys C. Baisa, Member (Ot 2:2 p.. Councilmember Sol P. Kaho`ohalahala, Member (In :0 .. Councilmember Bill Kauakea Medeiros, Member Councilmember Wayne K. Nishiki, Member Councilmember Michael P. Victorino, Member (Ot 2:24 p.. ECUSE: Councilmember Jo Anne Johnson, Member Councilmember Joseph Pontanilla, Member SA: Carla Nakata, Legislative Analyst Camille Sakamoto, Committee Secretary AMI.: Allan Delima, Administrative Officer, Department of Planning (It . ( Clayton Yoshida, Planning Program Administrator, Department of Planning (It . ( Tamara Horcajo, Director, Department of Parks and Recreation (It . (8 Frederick Pablo, Budget Director, Office of the Mayor (It . 46 Milton M. Arakawa, Director, Department of Public Works (It . 46 Moana M. Lutey, Deputy Corporation Counsel, Department of the Corporation Counsel (It . (, (8, nd (0 Richard B. Rost, Deputy Corporation Counsel, Department of the Corporation Counsel (It . (, (8, nd (0 David A. Galazin, Deputy Corporation Counsel, Department of the Corporation Counsel (It . 46 nd 40 Seated in the gallery: Brian T. Moto, Corporation Counsel, Department of the Corporation Counsel OES: Jocelyn Costa (It . 40 Johanna Kamaunu (It . 40 Kaniloa Kamaunu (It . 40 Wilmont Kn Khl (It . 40 Keeaumoku Kapu (It . 40 ESS: Akaku: Maui Community Television, Inc. COMMIEE O E WOE MIUES Cnl f th Cnt f M br 2, 200 CAI MOIA: . .(gavel). h Ctt f th Whl tn fr hrd, br 2nd, 200 ll n t rdr. r th rrd, hv n ttndn Mbr Gld .