Constitutions and Constitutional Conventions of Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICA's ANNEXATION of HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE

A LUSCIOUS FRUIT: AMERICA’S ANNEXATION OF HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE HOWARD JONES, COMMITTEE CHAIR JOSEPH A. FRY KARI FREDERICKSON LISA LIDQUIST-DORR STEVEN BUNKER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Becky L. Bruce 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the annexation of Hawaii was not the result of an aggressive move by the United States to gain coaling stations or foreign markets, nor was it a means of preempting other foreign nations from acquiring the island or mending a psychic wound in the United States. Rather, the acquisition was the result of a seventy-year relationship brokered by Americans living on the islands and entered into by two nations attempting to find their place in the international system. Foreign policy decisions by both nations led to an increasingly dependent relationship linking Hawaii’s stability to the U.S. economy and the United States’ world power status to its access to Hawaiian ports. Analysis of this seventy-year relationship changed over time as the two nations evolved within the world system. In an attempt to maintain independence, the Hawaiian monarchy had introduced a westernized political and economic system to the islands to gain international recognition as a nation-state. This new system created a highly partisan atmosphere between natives and foreign residents who overthrew the monarchy to preserve their personal status against a rising native political challenge. These men then applied for annexation to the United States, forcing Washington to confront the final obstacle in its rise to first-tier status: its own reluctance to assume the burdens and responsibilities of an imperial policy abroad. -

A Murder, a Trial, a Hanging: the Kapea Case of 1897–1898

esther k. arinaga & caroline a. garrett A Murder, a Trial, a Hanging: The Kapea Case of 1897–1898 Kapea was a 20 year-old Hawaiian man executed by hanging for the murder of Dr. Jared K. Smith of Köloa, Kaua‘i.1 Kapea’s 1897–98 arrest, trial, and execution in the fi nal years of the Republic of Hawai‘i illustrates legal, political, and cultural dynamics which found expres- sion in Hawai‘i’s courts during the critical years preceding Hawai‘i’s annexation to the United States. In 1874 David Kaläkaua succeeded Lunalilo as monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Aware that Native Hawaiians were increasingly dispossessed of their land and were further disenfranchised as disease drastically diminished their numbers, Kaläkaua set out to have his cabinet and legislature controlled by Native Hawaiians. Inevitably, he clashed with the white population, primarily missionary descendants. A duel ensued between a “willful Hawaiian King and a headstrong white opposition.” This was a new “band of righteous men,” who like earlier missionaries, felt it was their moral duty, the white man’s des- tiny, and in their own self-interest to govern and save the natives.2 In 1887 Kaläkaua’s reign began its swift descent. A new constitu- tion, forced upon the King at “bayonet” point, brought changes in Esther Kwon Arinaga is a retired public interest lawyer and has published essays on early women lawyers of Hawai‘i and Korean immigration to the United States. Caroline Axtell Garrett, retired from 40 years in higher education in Hawai‘i, has been publishing poems, essays, and articles since 1972. -

1887 Constitution of Hawaii ARTICLE 13. the Government Is Conducted

1887 Constitution of Hawaii ARTICLE 13. The Government is conducted for the common good, and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men. ARTICLE 20. The Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct. ARTICLE 21. The Government of this Kingdom is that of a Constitutional Monarchy, under His Majesty Kalakaua, His Heirs and Successors. ARTICLE 22. The Crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kalakaua, and to the Heirs of His body lawfully begotten, and to their lawful Descendants in a direct line; failing whom, the Crown shall descend to Her Royal Highness the Princess Liliuokalani, and the heirs of her body, lawfully begotten, and their lawful descendants in direct a line. ARTICLE 24. His Majesty Kalakaua, will, and his Successors shall take the following oath: I solemnly swear in the presence of Almighty God, to maintain the Constitution of the Kingdom whole and inviolate, and to govern in conformity therewith. ARTICLE 41. The Cabinet shall consist of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Finance, and the Attorney General, and they shall be His Majesty's special advisors in the executive affairs of the Kingdom; and they shall be ex-officio members of His Majesty's Privy Council of State. They shall be appointed and commissioned by the King and shall be removed by him, only upon a vote of want of confidence passed by a majority of all the elective members of the Legislature or upon conviction of felony, and shall be subject to impeachment. -

Hawaiians Should Be Portrayed in Popular Media

‘Okakopa (October) 2018 | Vol. 35, No. 10 THE LIVING WATER OF OHA www.oha.org/kwo ‘THE ING’ page K 12 ‘The The announcement of an upcoming movie about Kamehameha I opens discussion on how Hawaiians should be portrayed in popular media. INSIDE 2018 General election Guide - Photo: Nelson Gaspar Kıng’ $REAMINGOF THEFUTURE Hāloalaunuiakea Early Learning Center is a place where keiki love to go to school. It‘s also a safe place where staff feel good about helping their students to learn and prepare for a bright future. The center is run by Native Hawaiian U‘ilani Corr-Yorkman. U‘ilani wasn‘t always a business owner. She actually taught at DOE for 8 years. A Mālama Loan from OHA helped make her dream of owning her own preschool a reality. The low-interest loan allowed U‘ilani to buy fencing for the property, playground equipment, furniture, books…everything needed to open the doors of her business. U‘ilani and her staff serve the community in ‘Ele‘ele, Kaua‘i, and have become so popular that they have a waiting list. OHA is proud to support Native Hawaiian entrepreneurs in the pursuit of their business dreams. OHA‘s staff provide Native Hawaiian borrowers with personalized support and provide technical assistance to encourage the growth of Native Hawaiian businesses. Experience the OHA Loans difference. Call (808) 594-1924 or visit www.oha.org/ loans to learn how a loan from OHA can help grow your business. -A LAMA,OANS CANMAKEYOURDREAMSCOMETRUE (808) 594-1924 www.oha.org/loans follow us: /oha_hawaii | /oha_hawaii | fan us: /officeofhawaiianaffairs | Watch us: /OHAHawaii ‘okakopa2018 3 ‘o¯lelo a ka luna Ho‘okele messagE from the ceo bEing an informED votEr is your kulEana Aloha mai ka¯kou, istration. -

Crisis in Kona

Crisis in Kona Jean Greenwell October 22, 1868. Awful tidings from Kona. The false prophet, Kaona, has killed the sheriff. Entry from the Reverend Lorenzo Lyons' Journal.1 In 1868, the district of Kona, on the island of Hawai'i, made headlines throughout the Kingdom. Some of the many articles that appeared in the newspapers were entitled "The Crazy Prophet of South Kona," "Uprising in Kona," "Insurrection on Hawaii," "The Rebels," "A Religious Fanatic," and "Troubles on Hawaii."2 The person responsible for all this attention was a Hawaiian man named Joseph Kaona. The cult which arose around Kaona typified what is known as "nativistic religion." Ralph S. Kuykendall says: From the 1820's onward there were among the Hawaiians, as among other peoples, occasional examples of what anthropologists call 'nativistic religions,' commonly consisting of some odd form of religious observance or belief under the leadership of a 'prophet' who claimed to be inspired by divine revelation; frequently such religious manifestations combined features of Christianity with old Hawaiian beliefs and customs. .3 Kaona was born and brought up in Kainaliu, Kona on the island of Hawai'i. He received his education at the Hilo Boarding School and graduated from Lahainaluna on Maui.4 In 1851, in the aftermath of King Kamehameha III's great land Mahele, Kaona was employed surveying kuleana (property, titles, claims) in Ka'u, on the island of Hawai'i.5 He also surveyed a few kuleana on O'ahu.6 Later he was employed as a magistrate, both in Honolulu and in Lahaina.7 He was a well-educated native Hawaiian. -

Constitutional Issues Relating to Jury Trials

Hawaii Attorney General Legal Opinion 97-02 March 10, 1997 The Honorable Avery S. Chumbley The Honorable Matt M. Matsunaga Co-Chairs, Senate Committee on Judiciary The Nineteenth Legislature State of Hawaii State Capitol Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Dear Senators Chumbley and Matsunaga: Re: Constitutional Issues Relating to Jury Trials This is in response to your memorandum dated February 12, 1997, asking whether Senate Bill No. 201, titled "A Bill for an Act Relating to Jury Trials," presents any constitutional problems.1 Senate Bill No. 2012 permits the court to specify by rules the required number of jurors to sit on civil and criminal trials. The bill also authorizes parties to stipulate to a jury of less than twelve, but not less than six jurors. Finally, the bill requires cases involving "non-serious crimes" to be tried by juries of six persons. The constitutional provisions applicable to your inquiry are the Sixth and Seventh Amendments to the United States Constitution and sections 13 and 14 of article I of the Constitution of the State of Hawaii. While we see no federal constitutional objection to the use of a six-person jury in trials before the courts of this state (other than for "serious crimes," which are not covered by the proposed legislation), we believe that a constitutional amendment must be made to section 13 of article I of the State Constitution before a jury of less than twelve persons may be used for civil matters when the parties do not stipulate to a smaller jury panel. The proposed legislation does not conflict with the mandates of section 14 of article I of the Hawaii Constitution with regard to permitting a jury of six persons in cases involving "non-serious crimes." However, the existing provision in section 806-60, Hawaii Revised Statutes, that a "serious crime" triggering a right to a jury trial means a crime for which the defendant may be imprisoned for six months or more is erroneous given recent Hawaii Supreme Court caselaw. -

Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6t1nb227 No online items Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Brooke M. Black. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2002 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: mssEMR 1-1323 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers Dates (inclusive): 1766-1944 Bulk dates: 1860-1915 Collection Number: mssEMR 1-1323 Creator: Emerson, Nathaniel Bright, 1839-1915. Extent: 1,887 items. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Hawaiian physician and author Nathaniel Bright Emerson (1839-1915), including a a wide range of material such as research material for his major publications about Hawaiian myths, songs, and history, manuscripts, diaries, notebooks, correspondence, and family papers. The subjects covered in this collection are: Emerson family history; the American Civil War and army hospitals; Hawaiian ethnology and culture; the Hawaiian revolutions of 1893 and 1895; Hawaiian politics; Hawaiian history; Polynesian history; Hawaiian mele; the Hawaiian hula; leprosy and the leper colony on Molokai; and Hawaiian mythology and folklore. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

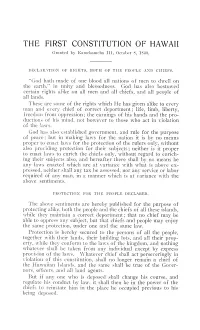

1840 Constitution

THE FIRST CONSTITUTION OF HAWAII Granted by Kamehameha III, October 8, 1840. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS, BOTH OF THE PEOPLE AND CHIEFS. "God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on the earth," in unity and blessedness. God has also bestowed certain rights alike on all men and all chiefs, and all people of all lands. These are some of the rights which He has given alike to every man and every chief of correct deportment; life, limb, liberty, freedom from oppression; the earnings of his hands and the pro- ductions of his mind, not however to those who act in violation of the laws. God has also established government, and rule for the purpose of peace ; but in making laws for the nation it is by no means proper to enact laws for the protection of the rulers only, without also providing protection for their subjects; neither is it proper to enact laws to enrich the chiefs only, without regard to enrich- ing their subjects also, and hereafter there shall by no means be any laws enacted which are at variance with what is above ex- pressed, neither shall any tax be assessed, nor any service or labor required of any man, in a manner which is at variance with the above sentiments. PROTECTION FOR THE PEOPLE DECLARED. The above sentiments are hereby published for the purpose of protecting alike, both the people and the chiefs of all these islands, while they maintain a correct deportment; that no chief may be able to oppress any subject, but that chiefs and people may enjoy the same protection, under one and the same law. -

A Portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF

HĀNAU MA KA LOLO, FOR THE BENEFIT OF HER RACE: a portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF BECKLEY NAKUINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HAWAIIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Jaime Uluwehi Hopkins Thesis Committee: Jonathan Kamakawiwoʻole Osorio, Chairperson Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa Wendell Kekailoa Perry DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Kanalu Young. When I was looking into getting a graduate degree, Kanalu was the graduate student advisor. He remembered me from my undergrad years, which at that point had been nine years earlier. He was open, inviting, and supportive of any idea I tossed at him. We had several more conversations after I joined the program, and every single one left me dizzy. I felt like I had just raced through two dozen different ideas streams in the span of ten minutes, and hoped that at some point I would recognize how many things I had just learned. I told him my thesis idea, and he went above and beyond to help. He also agreed to chair my committee. I was orignally going to write about Pana Oʻahu, the stories behind places on Oʻahu. Kanalu got the Pana Oʻahu (HWST 362) class put back on the schedule for the first time in a few years, and agreed to teach it with me as his assistant. The next summer, we started mapping out a whole new course stream of classes focusing on Pana Oʻahu. But that was his last summer. -

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources Materials Available at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Libraries Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Lori Kidani 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS CALL NUMBER LOCATIONS.....................................................................................................1 BIBLIOGRAPHIES......................................................................................................................2 CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE AND PROPERTY ............................................................................3 LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES.........................................................................................5 LAWS, CURRENT ......................................................................................................................9 LAWS, HISTORICAL ................................................................................................................10 LEGAL CASES .........................................................................................................................18 NATIVE RIGHTS AND CLAIMS................................................................................................20 OVERTHROW AND ANNEXATION..........................................................................................23 REFERENCE MATERIALS.......................................................................................................26 SOVEREIGNTY AND SELF DETERMINATION........................................................................27 -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

California Supreme Court by Gerald F

WESTERN LEGAL HISTORY THE JOURNAL OF THE NINTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT HISTORICAL SOCIETY VoLumE 2, NUMBER I WINTER/SPRING 1989 Western Legal Historyis published semi-annually, in spring and fall, by the Ninth judicial Circuit Historical Society, P.O. Box 2558, Pasadena, California 91102-2558, (818) 405-7059. The journal explores, analyzes, and presents the history of law, the legal profession, and the courts - particularly the federal courts - in Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Western Legal History is sent to members of the Society as well as members of affiliated legal historical societies in the Ninth Circuit. Membership is open to all. Membership dues (individuals and institutions): Patron, $1,000 or more; Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499; Sustaining, $100-$249; Advocate, $50-$99; Subscribing )non- members of the bench and bar, attorneys in practice fewer than five years, libraries, and academic institutions, $25-$49. Membership dues (law firms and corporations): Founder, $3,000 or more; Patron, $1,000-$2,999 Steward, $750-$999; Sponsor, $500-$749; Grantor, $250-$499. For information regarding membership, back issues of Western Legal History, and other Society publications and programs, please write or telephone. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to: Western Legal History P.O. Box 2558 Pasadena, California 91102-2558. Western Legal History disclaims responsibility for statements made by authors and for accuracy of footnotes. Copyright 1988 by the Ninth judicial Circuit Historical Society. ISSN 0896-2189. The Editorial Board welcomes unsolicited manuscripts, books for review, reports on research in progress, and recommendations for the journal.