THE PROCESS and OUTCOMES of the 2010 CONSTITUTONAL REFORM in TONGA a Study of the Devolution of Executive Authority from Monarc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Maori Authorities

TEENA BROWN PULU Minerals and Cucumbers in the Sea: International relations will transform the Tongan state Abstract Constitution law researcher Guy Powles, a Pakeha New Zealander residing in Australia was not optimistic accurate predictions on “the [Tonga] election which is coming up now in November” could be made (Garrett, 2014). “A man would be a fool to try to guess just where the balance will finish up,” he uttered to Jemima Garrett interviewing him for Radio Australia on April 30th 2014 (Garrett, 2014). Picturing the general election seven months away on November 27th 2014, Powles thought devolving the monarch’s executive powers to government by constitutional reform was Tonga’s priority. Whether it would end up an election issue deciding which way the public voted was a different story, and one he was not willing to take a punt on. While Tongans and non-Tongan observers focused attention on guessing who would get into parliament and have a chance at forming a government after votes had been casted in the November election, the trying political conditions the state functioned, floundered, and fell in, were overlooked. It was as if the Tongans and Palangi (white, European) commentators naively thought changing government would alter the internationally dictated circumstances a small island developing state was forced to work under. Teena Brown Pulu has a PhD in anthropology from the University of Waikato. She is a senior lecturer in Pacific development at AUT University. Her first book was published in 2011, Shoot the Messenger: The report on the Nuku’alofa reconstruction project and why the Government of Tonga dumped it. -

Political Reform in Tonga Responses to the Government's Roadmap

Political Reform in Tonga Responses to the Government’s Roadmap Sandra De Nardi, Roisin Lilley, Michael Pailthorpe and Andrew Curtin with Andrew Murray Catholic Institute of Sydney 2007 CIS 1 Political Reform in Tonga Table of Contents Introduction 3 Andrew Murray Tonga: Participation, Tradition and Constitution 4 Sandra De Nardi Political Reform in Tonga: Aristotelian Signposts 9 Roisin Lilley Moderating Tongan Reform 14 Michael Pailthorpe An Aristotelian Critique of Proposed Constitutional Reforms in Tonga 19 Andrew M Curtin Epilogue: Where to Now? 23 Andrew Murray Appendix: The Government of Tonga’s Roadmap for Political Reform 24 Catholic Institute of Sydney©2007 www.cis.catholic.edu.au Contact: [email protected] CIS 2 Political Reform in Tonga Introduction Andrew Murray SM The four essays in this collection are the best of the Events moved quickly in Tonga during 2006. final essays in the course unit, Social and Political Pressure had been building for some decades for Philosophy , in the Bachelor of Theology degree at reform of The Constitution of Tonga , established by Catholic Institute of Sydney during the second King George Tupou I in 1875 and still substantially semester of 2006. The course began with a careful unchanged. It constituted Tonga as a monarchy in reading of Aristotle’s Politics and went on to a which the King exercises full executive power and close reading of John Locke’s Second Treatise of in which nobles play a significant role. A National Government together with other source documents Committee for Political Reform (NCPR) was setup of modern political development. In parallel, the under the leadership of the Tu’ipelehake, the students began a cooperative project of studying nephew of the King. -

Study on Acquisition and Loss of Citizenship

COMPARATIVE REPORT 2020/01 COMPARATIVE FEBRUARY REGIONAL 2020 REPORT ON CITIZENSHIP LAW: OCEANIA AUTHORED BY ANNA DZIEDZIC © Anna Dziedzic, 2020 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Global Citizenship Observatory (GLOBALCIT) Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Comparative Regional Report on Citizenship Law: Oceania RSCAS/GLOBALCIT-Comp 2020/1 February 2020 Anna Dziedzic, 2020 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration, the expanding membership of the European Union, developments in Europe’s neighbourhood and the wider world. -

1887 Constitution of Hawaii ARTICLE 13. the Government Is Conducted

1887 Constitution of Hawaii ARTICLE 13. The Government is conducted for the common good, and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men. ARTICLE 20. The Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct. ARTICLE 21. The Government of this Kingdom is that of a Constitutional Monarchy, under His Majesty Kalakaua, His Heirs and Successors. ARTICLE 22. The Crown is hereby permanently confirmed to His Majesty Kalakaua, and to the Heirs of His body lawfully begotten, and to their lawful Descendants in a direct line; failing whom, the Crown shall descend to Her Royal Highness the Princess Liliuokalani, and the heirs of her body, lawfully begotten, and their lawful descendants in direct a line. ARTICLE 24. His Majesty Kalakaua, will, and his Successors shall take the following oath: I solemnly swear in the presence of Almighty God, to maintain the Constitution of the Kingdom whole and inviolate, and to govern in conformity therewith. ARTICLE 41. The Cabinet shall consist of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Finance, and the Attorney General, and they shall be His Majesty's special advisors in the executive affairs of the Kingdom; and they shall be ex-officio members of His Majesty's Privy Council of State. They shall be appointed and commissioned by the King and shall be removed by him, only upon a vote of want of confidence passed by a majority of all the elective members of the Legislature or upon conviction of felony, and shall be subject to impeachment. -

Hawaiians Should Be Portrayed in Popular Media

‘Okakopa (October) 2018 | Vol. 35, No. 10 THE LIVING WATER OF OHA www.oha.org/kwo ‘THE ING’ page K 12 ‘The The announcement of an upcoming movie about Kamehameha I opens discussion on how Hawaiians should be portrayed in popular media. INSIDE 2018 General election Guide - Photo: Nelson Gaspar Kıng’ $REAMINGOF THEFUTURE Hāloalaunuiakea Early Learning Center is a place where keiki love to go to school. It‘s also a safe place where staff feel good about helping their students to learn and prepare for a bright future. The center is run by Native Hawaiian U‘ilani Corr-Yorkman. U‘ilani wasn‘t always a business owner. She actually taught at DOE for 8 years. A Mālama Loan from OHA helped make her dream of owning her own preschool a reality. The low-interest loan allowed U‘ilani to buy fencing for the property, playground equipment, furniture, books…everything needed to open the doors of her business. U‘ilani and her staff serve the community in ‘Ele‘ele, Kaua‘i, and have become so popular that they have a waiting list. OHA is proud to support Native Hawaiian entrepreneurs in the pursuit of their business dreams. OHA‘s staff provide Native Hawaiian borrowers with personalized support and provide technical assistance to encourage the growth of Native Hawaiian businesses. Experience the OHA Loans difference. Call (808) 594-1924 or visit www.oha.org/ loans to learn how a loan from OHA can help grow your business. -A LAMA,OANS CANMAKEYOURDREAMSCOMETRUE (808) 594-1924 www.oha.org/loans follow us: /oha_hawaii | /oha_hawaii | fan us: /officeofhawaiianaffairs | Watch us: /OHAHawaii ‘okakopa2018 3 ‘o¯lelo a ka luna Ho‘okele messagE from the ceo bEing an informED votEr is your kulEana Aloha mai ka¯kou, istration. -

Constitutional Issues Relating to Jury Trials

Hawaii Attorney General Legal Opinion 97-02 March 10, 1997 The Honorable Avery S. Chumbley The Honorable Matt M. Matsunaga Co-Chairs, Senate Committee on Judiciary The Nineteenth Legislature State of Hawaii State Capitol Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Dear Senators Chumbley and Matsunaga: Re: Constitutional Issues Relating to Jury Trials This is in response to your memorandum dated February 12, 1997, asking whether Senate Bill No. 201, titled "A Bill for an Act Relating to Jury Trials," presents any constitutional problems.1 Senate Bill No. 2012 permits the court to specify by rules the required number of jurors to sit on civil and criminal trials. The bill also authorizes parties to stipulate to a jury of less than twelve, but not less than six jurors. Finally, the bill requires cases involving "non-serious crimes" to be tried by juries of six persons. The constitutional provisions applicable to your inquiry are the Sixth and Seventh Amendments to the United States Constitution and sections 13 and 14 of article I of the Constitution of the State of Hawaii. While we see no federal constitutional objection to the use of a six-person jury in trials before the courts of this state (other than for "serious crimes," which are not covered by the proposed legislation), we believe that a constitutional amendment must be made to section 13 of article I of the State Constitution before a jury of less than twelve persons may be used for civil matters when the parties do not stipulate to a smaller jury panel. The proposed legislation does not conflict with the mandates of section 14 of article I of the Hawaii Constitution with regard to permitting a jury of six persons in cases involving "non-serious crimes." However, the existing provision in section 806-60, Hawaii Revised Statutes, that a "serious crime" triggering a right to a jury trial means a crime for which the defendant may be imprisoned for six months or more is erroneous given recent Hawaii Supreme Court caselaw. -

The Power of Veto in Pacific Island States and the Case of Tonga

1 THE HEAD OF STATE AND THE LEGISLATURE: THE POWER OF VETO IN PACIFIC ISLAND STATES AND THE CASE OF TONGA Guy Powles* C'est avec une profonde tristesse que les membres des comités de rédaction et scientifique du Comparative Law Journal of the Pacific ont appris le décès du Dr Guy Powles, survenu le 20 juillet 2016. Ils s'associent au chagrin de sa famille. Unanimement reconnu par la communauté scientifique comme l'un des meilleurs connaisseurs de systèmes juridiques en vigueur dans le Pacifique Sud, son érudition n'avait d'égale que sa profonde humanité. Constitutionaliste et comparatiste hors pair, encourageant sans cesse les initiatives de nature à promouvoir toutes les facettes de l'étude du droit dans le Pacifique, il avait bien voulu réserver au Comparative Law Journal of the Pacific, la première parution de ce qui allait rapidement devenir un ouvrage de référence, de son important travail sur les réformes constitutionnelles du royaume des Tonga Political and Constitutional Reform Opens the Door: The Kingdom of Tonga's Path to Democracy (2012) CLJP-HS vol 12. La présence du Dr Guy Powles au sein du comité scientifique du Comparative Law Journal of the Pacific etait un honneur mais aussi la plus belle des cautions scientifiques qu'une revue de droit comparé ait pu espérer dans le Pacifique Sud. Aujourd'hui encore le Comparative Law Journal of the Pacific a le privilège de pouvoir publier dans ce volume qui est dédié à sa mémoire, les deux derniers articles qu'il avait rédigés quelque temps avant son décès. * Dr Guy Powles, latterly of Monash University, 1934-2016. -

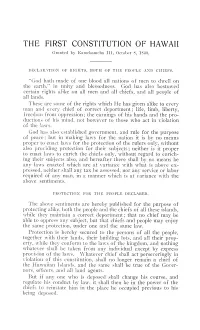

1840 Constitution

THE FIRST CONSTITUTION OF HAWAII Granted by Kamehameha III, October 8, 1840. DECLARATION OF RIGHTS, BOTH OF THE PEOPLE AND CHIEFS. "God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell on the earth," in unity and blessedness. God has also bestowed certain rights alike on all men and all chiefs, and all people of all lands. These are some of the rights which He has given alike to every man and every chief of correct deportment; life, limb, liberty, freedom from oppression; the earnings of his hands and the pro- ductions of his mind, not however to those who act in violation of the laws. God has also established government, and rule for the purpose of peace ; but in making laws for the nation it is by no means proper to enact laws for the protection of the rulers only, without also providing protection for their subjects; neither is it proper to enact laws to enrich the chiefs only, without regard to enrich- ing their subjects also, and hereafter there shall by no means be any laws enacted which are at variance with what is above ex- pressed, neither shall any tax be assessed, nor any service or labor required of any man, in a manner which is at variance with the above sentiments. PROTECTION FOR THE PEOPLE DECLARED. The above sentiments are hereby published for the purpose of protecting alike, both the people and the chiefs of all these islands, while they maintain a correct deportment; that no chief may be able to oppress any subject, but that chiefs and people may enjoy the same protection, under one and the same law. -

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources Materials Available at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Libraries Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Lori Kidani 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS CALL NUMBER LOCATIONS.....................................................................................................1 BIBLIOGRAPHIES......................................................................................................................2 CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE AND PROPERTY ............................................................................3 LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES.........................................................................................5 LAWS, CURRENT ......................................................................................................................9 LAWS, HISTORICAL ................................................................................................................10 LEGAL CASES .........................................................................................................................18 NATIVE RIGHTS AND CLAIMS................................................................................................20 OVERTHROW AND ANNEXATION..........................................................................................23 REFERENCE MATERIALS.......................................................................................................26 SOVEREIGNTY AND SELF DETERMINATION........................................................................27 -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

Housing, Land and Property Law in Tonga

Housing, Land and Property Law in Tonga 1 Key laws and actors Laws The main laws governing housing, land, building and planning are the Constitution, the Land Act 1927, the National Spatial Planning and Management Act 2012 and the Building Control and Standards Act 2002. Key The Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources is responsible for land administration. government The Ministry houses the National Spatial Planning Authority, which is responsible for actors administering planning law. In the event of a disaster, the National Emergency Operations Committee (NEOC) is responsible for coordinating the response. The NEOC is supported by District Emergency Management Committees (DEMC) and Village Emergency Committees (VEC). There is a DEMC for each of the five districts: Ha’apai, Vava’u, Niuatoputapu, Niuafo’ou and ‘Eua. Shelter cluster The contact details for key Shelter Cluster personnel are provided in Section 5 below. 2 Common types of tenure Almost all types of land tenure in Tonga must be created or transferred through registration. Unlike many countries in the Pacific, Tonga does not have a dual system of customary ownership and registered ownership. The table below summarises the most common types of tenure in Tonga. Tenure Commonly Key Features Title document Registered? Crown land n/a Land owned by the government. n/a Hereditary Yes A life interest held by a Noble (tofia) or Chief Tofia certificate estate (matapule) and passed down from father to son. Town Yes A life interest held by a single Tongan male and used Deed of Grant allotment for residential purposes. Passed down from father to son. -

387 DAFTAR PUSTAKA A. Buku AH Nasution. Menegakkan

387 DAFTAR PUSTAKA A. Buku A. H. Nasution. Menegakkan Keadilan dan Kebenaran I. Djakarta: Seruling Masa, 1967. -------------------. Menegakkan Keadilan dan Kebenaran II. Djakarta: Seruling Mas, 1967. A. Muhammad Asrun (ed.). 70 Tahun Ismail Suny; Bergelut Dengan Ilmu Berkiprah Dalam Politik. Jakarta: Pustaka Sinar Harapan, 2000. A.A. Oka Mahendra dan Soekedy. Sistem Multi Partai; Prospek Politik Pasca 2004. Jakarta: Yayasan Pancur Siwah, 2004. A.K. Pringgodigdo. Kedudukan Presiden Menurut Tiga Undang-Undang dasar Dalam Teori dan Praktek. Djakarta: P.T. Pembangunan, 1956. Aa, H. Undang-Undang Negara Republik Indonesia. Djilid I. Djakarta – Bandung: Neijenhuis & Co., 1950. Abdul Bari Azed dan Makmur Amir. Pemilu & Partai Politik Di Indonesia. Jakarta: Pusat Studi Hukum Tata Negara Fakultas Hukum Universitas Indonesia, 2005 Abdul Mukthie Fadjar. Hukum Konstitusi Dan Mahkamah Konstitusi. Jakarta: Sekretariat Jenderal dan Kepaniteraan Mahkamah Konstitusi RI, 2006. Adnan Buyung Nasution. Aspirasi Pemerintahan Konstitusional di Indonesia; Studi Sosio-Legal atas Konstituante 1956 – 1959. Cetakan Kedua. Jakarta: PT Pustaka Utama Grafiti, 2001. Afan Gaffar, dkk. Golkar Dan Demokratisasi Di Indonesia. Yogyakarta: PPSK, 1993. Ahmad Syafii Maarif. Studi Tentang Percaturan dalam Konstituante: Islam Dan Masalah Kenegaraan. Jakarta: LP3ES, 1985. Aisyah Aminy. Pasang Surut Peran DPR – MPR 1945 – 2004. Jakarta: Yayasan Pancur Siwah, 2004. Alder, John and Peter English. Constitutional and Administrative Law. Hampshire-London: Macmillan Education Ltd., 1989. Alfian. Pemikiran Dan Perubahan Politik Indonesia. Jakarta: PT. Gramedia Pustaka Utama, 1992. Pembubaran partai ..., Muchamad Ali Safa’at, FH UI., 2009. Universitas Indonesia 388 Alford, Robert R., and Roger Friedland. Power Theory: Capitalism, the state, and democracy. Cambridge-New York-Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1985. Ali Moertopo.