Canada's “Newer Constitutional Law”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitor Ccpa

CCPA MONITOR ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PERSPECTIVES Volume 21 No. 7 Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives December 2014 / January 2015 Maher Arar – Ten Years Later Still waiting for proper oversight of security and intelligence activities By Gar Pardy (Photo by Adam(Photo Scotti) Former ambassador and long-serving diplomat Gar Pardy delivered t has been a long day. It has been an even a longer the following speech to a conference in Ottawa on October 29 called week in the affairs of our country. The events, last week, Arar+10: National Security and Human Rights, A Decade Ileading to the murder of two members of the Canadian Later. The day-long event, co-organized by Amnesty International, Armed Forces, have provoked commentaries ranging from the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group, the Human Rights the ridiculous to the profound. Each in its own way provides Research and Education Centre, and the Centre for International a tragic backdrop to the substance of this conference. Policy Studies, brought together judges, lawyers, journalists and It is important we dismiss the idea that something called rights defenders to discuss the personal dimension of national Canadian “innocence” has been lost in the midst of these security–related human rights violations, challenges for the legal tragic events. Unfortunately, a Canada “innocent” from the profession, and ongoing concerns related to oversight of national troubles of the world is one of our national conceits that do security activities. Pardy, a self-described son of the Rock, was the head not withstand close examination. of consular affairs at the Department of Foreign Affairs at the time of A more telling observation may have come from an ad Canadian citizen Maher Arar’s rendition from the United States to in last Thursday’s Globe and Mail. -

Special Series on the Federal Dimensions of Reforming the Supreme Court of Canada

SPECIAL SERIES ON THE FEDERAL DIMENSIONS OF REFORMING THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA The Supreme Court of Canada: A Chronology of Change Jonathan Aiello Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University SC Working Paper 2011 21 May 1869 Intent on there being a final court of appeal in Canada following the Bill for creation of a Supreme country’s inception in 1867, John A. Macdonald, along with Court is withdrawn statesmen Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Mackenzie and Edward Blake propose a bill to establish the Supreme Court of Canada. However, the bill is withdrawn due to staunch support for the existing system under which disappointed litigants could appeal the decisions of Canadian courts to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) sitting in London. 18 March 1870 A second attempt at establishing a final court of appeal is again Second bill for creation of a thwarted by traditionalists and Conservative members of Parliament Supreme Court is withdrawn from Quebec, although this time the bill passed first reading in the House. 8 April 1875 The third attempt is successful, thanks largely to the efforts of the Third bill for creation of a same leaders - John A. Macdonald, Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Supreme Court passes Mackenzie and Edward Blake. Governor General Sir O’Grady Haly gives the Supreme Court Act royal assent on September 17th. 30 September 1875 The Honourable William Johnstone Ritchie, Samuel Henry Strong, The first five puisne justices Jean-Thomas Taschereau, Télesphore Fournier, and William are appointed to the Court Alexander Henry are appointed puisne judges to the Supreme Court of Canada. -

Total of !0 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

TOTAL OF !0 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) Liberalism in Winnipeg, 1890s-1920s: Charles W. Gordon, John W. Dafoe, Minnie J.B. Campbell, and Francis M. Beynon by © Kurt J. Korneski A thesis submitted to the school of graduate studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Memorial University of Newfoundland April2004 DEC 0 5 2005 St. John's Newfoundland Abstract During the first quarter of the twentieth century Canadians lived through, were shaped by, and informed the nature of a range of social transformations. Social historians have provided a wealth of information about important aspects of those transformations, particularly those of"ordinary" people. The purpose of this thesis is to provide further insight into these transitions by examining the lives and thoughts of a selection of those who occupied a comparatively privileged position within Canadian society in the early twentieth century. More specifically, the approach will be to examine four Winnipeg citizens - namely, Presbyterian minister and author Charles W. Gordon, newspaper editor John W. Dafoe, member of the Imperial Order Daughters of Empire Minnie J.B. Campbell, and women's page editor Francis M. Beynon. In examining these men and women, what becomes evident about elites and the social and cultural history of early twentieth-century Canada is that, despite their privileged standing, they did not arrive at "reasonable" assessments of the state of affairs in which they existed. Also, despite the fact that they and their associates were largely Protestant, educated Anglo-Canadians from Ontario, it is apparent that the men and women at the centre of this study suggest that there existed no consensus among elites about the proper goals of social change. -

Debates of the Senate

Debates of the Senate 2nd SESSION . 41st PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 149 . NUMBER 88 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Thursday, October 23, 2014 The Honourable NOËL A. KINSELLA Speaker CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: D'Arcy McPherson, National Press Building, Room 906, Tel. 613-995-5756 Publications Centre: David Reeves, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 613-947-0609 Published by the Senate Available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 2294 THE SENATE Thursday, October 23, 2014 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. [English] [Translation] The Sergeant-at-Arms of the House of Commons, Mr. Kevin Vickers, is the one who put an end to the rampage of the individual who was hiding in the columns at the entrance of PRAYERS the Library of Parliament. The rest of the day was spent in fear and anxiety for the hundreds of people who go about their duties The Hon. the Speaker: Almighty God, we beseech thee to every day in Centre Block. protect our Queen and to bless the people of Canada. Guide us in our endeavours; let your spirit preside over our deliberations so [Translation] that, at this time assembled, we may serve ever better the cause of peace and justice in our land and throughout the world. Amen. If there is one thing that human beings know how to do in the midst of such terrifying and intense moments, it is to stand together and help one another. FALLEN SOLDIER That is what we saw throughout the day yesterday. -

The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

The Judicial Function under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky* The author surveys the various American L'auteur resume les differentes theories am6- theories of judicial review in an attempt to ricaines du contr61e judiciaire dans le but de suggest approaches to a Canadian theory of sugg6rer une th6orie canadienne du r8le des the role of the judiciary under the Canadian juges sous Ia Charte canadiennedes droits et Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A detailed libert~s. Notamment, une 6tude d6taille de examination of the legislative histories of sec- 'histoire 1fgislative des articles 1, 52 et 33 de ]a Charte d6montre que les r~dacteurs ont tions 1, 52 and 33 of the Charterreveals that voulu aller au-delA de la Dclarationcana- the drafters intended to move beyond the Ca- dienne des droits et 6liminer le principe de ]a nadianBill ofRights and away from the prin- souverainet6 parlementaire. Cette intention ciple of parliamentary sovereignty. This ne se trouvant pas incorpor6e dans toute sa intention was not fully incorporated into the force au texte de Ia Charte,la protection des Charter,with the result that, properly speak- droits et libert~s au Canada n'est pas, Apro- ing, Canada's constitutional bill of rights is prement parler, o enchfiss~e )) dans ]a cons- not "entrenched". The author concludes by titution. En conclusion, l'auteur met 'accent emphasizing the establishment of a "contin- sur l'instauration d'un < colloque continu uing colloquy" involving the courts, the po- auxquels participeraient les tribunaux, les litical institutions, the legal profession and institutions politiques, ]a profession juri- society at large, in the hope that the legiti- dique et le grand public; ]a l6gitimit6 de la macy of the judicial protection of Charter protection judiciaire des droits garantis par rights will turn on the consent of the gov- la Charte serait alors fond6e sur la volont6 erned and the perceived justice of the courts' des constituants et Ia perception populaire de decisions. -

UNIVERSITY of MANITOBA JOHN WESLEY DAFOE 31St ANNUAL

UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA JOHN WESLEY DAFOE 31st ANNUAL POLITICAL STUDIES STUDENT CONFERENCE THE GREAT WARS: MARKING HISTORY AND HUMANITY 29 JANUARY 2015 ANDREA CHARRON = University of Manitoba (Standing ovation for the opening of John Wesley Dafoe Student Conference) Thursday and Friday at University College discussed Conference is free and open to the public No students present were alive for the Great Wars Reference to Dr. Allan Levine delivering the introductory Paul Buteux Memorial Lecture. Professor Buteux was known as “Mr. Nuclear Deterrence.” But he was most known for commitment to his students. Dr. Levine’s talk is entitled: “The Great Wars: Marking History and Humanity” Allan Levine is a historian and the author of “Toronto: A Biography of a City.” He has written for the Winnipeg Free Press and the National Post about the impact of the World Wars. ALLAN LEVINE – THE PAUL BUTEUX MEMORIAL LECTURE The Great Wars: Marking History and Humanity Reference to the Department of Political Studies and 1974 studying Introduction to Political Science with Wally Fox-Decent smoking his pipe. Allan was interested in the reform of the Senate and received a B or B+ on his essay. He found the topic broad and the key issues are still valid one hundred years later. The scale of the carnage in 1918 was enormous, with 10 million combatants and 7 million civilians killed. Approximately 65 thousand Canadians died in World War I. With the Holocaust, double the numbers died in World War II, with 60 million killed, including 6 million Jews and 45 thousand Canadians. A total of 65 to 70 million people were killed in both wars. -

Newer Constitutional Law” and the Idea of Constitutional Rights

Canada’s “Newer Constitutional Law” and the Idea of Constitutional Rights Eric M. Adams* This article places F.R. Scott’s 1935 call for L’article situe l’appel de F.R. Scott de 1935 pour entrenched constitutional rights within the context of des droits constitutionnels enchâssés dans le contexte marked changes in constitutional scholarship in the des grands changements ayant marqués la doctrine 2006 CanLIIDocs 90 1930s—what the author refers to as the “newer constitutionnelle durant les années 1930, ce que constitutional law”. Influenced by broader currents in l’auteur considère comme le «newer constitutional legal theory and inspired by the political and economic law». Influencés par des courants de théorie légale plus upheavals of the Depression, constitutional scholars diversifiés et inspirés par les bouleversements broke away from the formalist traditions of a previous politiques et économiques de la Grande Dépression, les generation and engaged in new ways of thinking and érudits du droit constitutionnel se sont détachés du writing about Canadian constitutional law. In this new formalisme de leurs prédécesseurs et ont mis de l’avant approach, scholars questioned Canada’s constitutional de nouvelles façons d’aborder le droit constitutionnel connection to Britain and argued instead for a made-in- canadien. Cette nouvelle approche a amené les auteurs Canada constitutional law that could functionally à remettre en question le lien constitutionnel entre le address the changing needs of Canada and its citizens. Canada et la Grande-Bretagne et à avancer l’idée d’un In the process, scholars legitimated the prospects and droit constitutionnel propre au Canada, qui répondrait possibilities of constitutional adaptation and change. -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

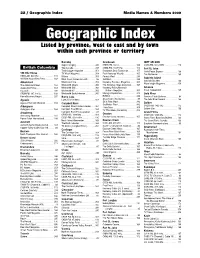

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University. -

Click Here to Download the PDF File

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. AN ARCHAEOLOGY OF KEYNESIANISM: THE MACRO-POLITICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE MODERN WELFARE STATE IN CANADA 1896-1948 by Timothy Bruce Krywulak, B.A (Hons.), M.A A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario 5 August 2005 © copyright 2005, Tim Kiywulak Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home And

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 A Dissertation Presented by Shannon Jaleen Grove to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor oF Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University May 2014 Copyright by Shannon Jaleen Grove 2014 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Shannon Jaleen Grove We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Michele H. Bogart – Dissertation Advisor Professor, Department of Art Barbara E. Frank - Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, Department of Art Raiford Guins - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory Brian Rusted - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art / Department of Communication and Culture University of Calgary This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 by Shannon Jaleen Grove Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2014 This dissertation analyzes nationalisms in the work of Canadian magazine illustrators in Toronto and New York, 1880 to 1960. Using a continentalist approach—rather than the nationalist lens often employed by historians of Canadian art—I show the existence of an integrated, joint North American visual culture. Drawing from primary sources and biography, I document the social, political, corporate, and communication networks that illustrators traded in. I focus on two common visual tropes of the day—that of the pretty girl and that of wilderness imagery.