Magic and Witchcraft : Critical Concepts in Historical Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Magic & White Supremacy

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 2-23-2021 Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power Nicholas Charles Peters Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Peters, Nicholas Charles, "Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power" (2021). University Honors Theses. Paper 962. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Black Magic & White Supremacy: Witchcraft as an Allegory for Race and Power By Nicholas Charles Peters An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in English and University Honors Thesis Adviser Dr. Michael Clark Portland State University 2021 1 “Being burned at the stake was an empowering experience. There are secrets in the flames, and I came back with more than a few” (Head 19’15”). Burning at the stake is one of the first things that comes to mind when thinking of witchcraft. Fire often symbolizes destruction or cleansing, expelling evil or unnatural things from creation. “Fire purges and purifies... scatters our enemies to the wind. -

Wicca 1739 Have Allowed for His Continued Popularity

Wicca 1739 have allowed for his continued popularity. Whitman’s According to Gardner, witchcraft had survived the per- willingness to break out of hegemonic culture and its secutions of early modern Europe and persisted in secret, mores in order to celebrate the mundane and following the thesis of British folklorist and Egyptologist unconventional has ensured his relevance today. His belief Margaret Murray (1862–1963). Murray argued in her in the organic connection of all things, coupled with his book, The Witch Cult in Western Europe (1921), that an old organic development of a poetic style that breaks with religion involving a horned god who represented the fertil- many formal conventions have caused many scholars and ity of nature had survived the persecutions and existed critics to celebrate him for his innovation. His idea of uni- throughout Western Europe. Murray wrote that the versal connection and belief in the spirituality present in a religion was divided into covens that held regular meet- blade of grass succeeded in transmitting a popularized ings based on the phases of the moon and the changes of version of Eastern theology and Whitman’s own brand of the seasons. Their rituals included feasting, dancing, sac- environmentalism for generations of readers. rifices, ritualized sexual intercourse, and worship of the horned god. In The God of the Witches (1933) Murray Kathryn Miles traced the development of this god and connected the witch cult to fairy tales and Robin Hood legends. She used Further Reading images from art and architecture to support her view that Greenspan, Ezra, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Whit- an ancient vegetation god and a fertility goddess formed man. -

Muslim American's Understanding of Women's

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2018 MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS Riba Khaleda Eshanzada Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Eshanzada, Riba Khaleda, "MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS" (2018). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 637. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/637 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master in Social Work by Riba Khaleda Eshanzada June 2018 MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Riba Khaleda Eshanzada June 2018 Approved by: Dr. Erica Lizano, Research Project Supervisor Dr. Janet Chang, M.S.W. Research Coordinator © 2018 Riba Khaleda Eshanzada ABSTRACT Islam is the most misrepresented, misunderstood, and the subject for much controversy in the United States of America especially with the women’s rights issue. This study presents interviews with Muslim Americans on their narrative and perspective of their understanding of women’s rights in accordance to the Islamic traditions. -

'A Great Or Notorious Liar': Katherine Harrison and Her Neighbours

‘A Great or Notorious Liar’: Katherine Harrison and her Neighbours, Wethersfield, Connecticut, 1668 – 1670 Liam Connell (University of Melbourne) Abstract: Katherine Harrison could not have personally known anyone as feared and hated in their own home town as she was in Wethersfield. This article aims to explain how and why this was so. Although documentation is scarce for many witch trials, there are some for which much crucial information has survived, and we can reconstruct reasonably detailed accounts of what went on. The trial of Katherine Harrison of Wethersfield, Connecticut, at the end of the 1660s is one such case. An array of factors coalesced at the right time in Wethersfield for Katherine to be accused. Her self-proclaimed magical abilities, her socio- economic background, and most of all, the inter-personal and legal conflicts that she sustained with her neighbours all combined to propel this woman into a very public discussion about witchcraft in 1668-1670. The trial of Katherine Harrison was a vital moment in the development of the legal and theological responses to witchcraft in colonial New England. The outcome was the result of a lengthy process jointly negotiated between legal and religious authorities. This was the earliest documented case in which New England magistrates trying witchcraft sought and received explicit instruction from Puritan ministers on the validity of spectral evidence and the interface between folk magic and witchcraft – implications that still resonated at the more recognised Salem witch trials almost twenty-five years later. The case also reveals the social dynamics that caused much ambiguity and confusion in this early modern village about an acceptable use of the occult. -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

Constructing the Witch in Contemporary American Popular Culture

"SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES": CONSTRUCTING THE WITCH IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Catherine Armetta Shufelt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Committee: Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor Dr. Andrew M. Schocket Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Donald McQuarie Dr. Esther Clinton © 2007 Catherine A. Shufelt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor What is a Witch? Traditional mainstream media images of Witches tell us they are evil “devil worshipping baby killers,” green-skinned hags who fly on brooms, or flaky tree huggers who dance naked in the woods. A variety of mainstream media has worked to support these notions as well as develop new ones. Contemporary American popular culture shows us images of Witches on television shows and in films vanquishing demons, traveling back and forth in time and from one reality to another, speaking with dead relatives, and attending private schools, among other things. None of these mainstream images acknowledge the very real beliefs and traditions of modern Witches and Pagans, or speak to the depth and variety of social, cultural, political, and environmental work being undertaken by Pagan and Wiccan groups and individuals around the world. Utilizing social construction theory, this study examines the “historical process” of the construction of stereotypes surrounding Witches in mainstream American society as well as how groups and individuals who call themselves Pagan and/or Wiccan have utilized the only media technology available to them, the internet, to resist and re- construct these images in order to present more positive images of themselves as well as build community between and among Pagans and nonPagans. -

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional Sections Contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D

DIVINATION SYSTEMS Written by Nicole Yalsovac Additional sections contributed by Sean Michael Smith and Christine Breese, D.D. Ph.D. Introduction Nichole Yalsovac Prophetic revelation, or Divination, dates back to the earliest known times of human existence. The oldest of all Chinese texts, the I Ching, is a divination system older than recorded history. James Legge says in his translation of I Ching: Book Of Changes (1996), “The desire to seek answers and to predict the future is as old as civilization itself.” Mankind has always had a desire to know what the future holds. Evidence shows that methods of divination, also known as fortune telling, were used by the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Babylonians and the Sumerians (who resided in what is now Iraq) as early as six‐thousand years ago. Divination was originally a device of royalty and has often been an essential part of religion and medicine. Significant leaders and royalty often employed priests, doctors, soothsayers and astrologers as advisers and consultants on what the future held. Every civilization has held a belief in at least some type of divination. The point of divination in the ancient world was to ascertain the will of the gods. In fact, divination is so called because it is assumed to be a gift of the divine, a gift from the gods. This gift of obtaining knowledge of the unknown uses a wide range of tools and an enormous variety of techniques, as we will see in this course. No matter which method is used, the most imperative aspect is the interpretation and presentation of what is seen. -

Course Outline

COURSE OUTLINE OXNARD COLLEGE I. Course Identification and Justification: A. Proposed course id: ANTH R111H Banner title: Honors: Magic Witchcraft Relig Full title: Honors: Magic, Witchcraft and Religion: Anthropology of Belief B. Reason(s) course is offered: This is part of the Anthropology AA-T. This course fulfills lower division anthropology requirements at the UC and CSU. It is also part of the IGETC Transfer Curriculum pattern. It is one of the recommended electives for an A.A. in anthropology at Oxnard College. It fulfills area D for CSU. II. Catalog Information: A. Units: Current: 3.00 B. Course Hours: 1. In-Class Contact Hours: Lecture: 52.5 Activity: 0 Lab: 0 2. Total In-Class Contact Hours: 52.5 3. Total Outside-of-Class Hours: 105 4. Total Student Learning Hours: 157.5 C. Prerequisites, Corequisites, Advisories, and Limitations on Enrollment: 1. Prerequisites Current: 2. Corequisites Current: 3. Advisories: Current: 4. Limitations on Enrollment: Current: D. Catalog Description: Current: Religion and magic are human universals. Anthropologists study contemporary religions and religious consciousness to help reconstruct religions in prehistory, as well as for an understanding of the modern world and of the human mind. The student will be introduced to a fascinating variety of rites, rituals, religious movements, symbolic systems, as well as anthropological theories about religion. Honors work challenges students to be more analytical and creative through expanded assignments, real-world applications and enrichment opportunities. Credit will not be awarded for both the honors and regular versions of a course. Credit will be awarded only for the first course completed with a grade of C or “P” or better. -

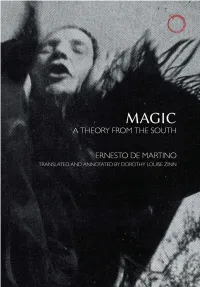

Magic: a Theory from the South

MAGIC Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com Magic A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH Ernesto de Martino Translated and Annotated by Dorothy Louise Zinn Hau Books Chicago © 2001 Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore Milano (First Edition, 1959). English translation © 2015 Hau Books and Dorothy Louise Zinn. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-9-9 LCCN: 2014953636 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Contents Translator’s Note vii Preface xi PART ONE: LUcanian Magic 1. Binding 3 2. Binding and eros 9 3. The magical representation of illness 15 4. Childhood and binding 29 5. Binding and mother’s milk 43 6. Storms 51 7. Magical life in Albano 55 PART TWO: Magic, CATHOliciSM, AND HIGH CUltUre 8. The crisis of presence and magical protection 85 9. The horizon of the crisis 97 vi MAGIC: A THEORY FROM THE SOUTH 10. De-historifying the negative 103 11. Lucanian magic and magic in general 109 12. Lucanian magic and Southern Italian Catholicism 119 13. Magic and the Neapolitan Enlightenment: The phenomenon of jettatura 133 14. Romantic sensibility, Protestant polemic, and jettatura 161 15. The Kingdom of Naples and jettatura 175 Epilogue 185 Appendix: On Apulian tarantism 189 References 195 Index 201 Translator’s Note Magic: A theory from the South is the second work in Ernesto de Martino’s great “Southern trilogy” of ethnographic monographs, and following my previous translation of The land of remorse ([1961] 2005), I am pleased to make it available in an English edition. -

Chapter Four the World Beyond the Picture Frame

CHAPTER FOUR THE WORLD BEYOND THE PICTURE FRAME There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy. Hamlet, Act I Scene V. It is venturesome to think that a coordination of words (philosophies are nothing more than that) can resemble the universe very much. Jorge Luis Borges: Labyrinths In the previous chapter we discussed certain events that took place during the period centered about the year 1600--events which turned out to be the opening guns in the Scientific Revolution. However, as a description of the Human Experience peculiar to that time, our story remains incomplete, for it lacks a vital ingredient. By way of analogy, consider a history of that same era, written a hundred years later, during the 18th century. It would have been a chronicle of popes and kings, and their battles, with an occasional genuflection to great literary works of the past, such as those of a Shakespeare or a Milton. History, then, is a matter of taste, a tale about what someone considered to be important. And the power structure of a civilization is always the principal patron of the historians, and therefore also the arbiter of taste. Since such an arrangement is, figuratively speaking, somewhat anaerobic, it might be useful to "challenge the dominant paradigm," thereby letting in some fresh air. Included in the following pages, are three instances of human experience that are clearly discordant with The Myth of Modern Civilization. There is no reason to believe that all of these testimonies were necessarily falsehoods. But first, in order to understand the background for these stories, we need to examine the events that took place in Italy as a result of the Protestant Reformation, which had begun in the year 1517. -

Magic, Greek Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2019 Magic, Greek Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. 2019. "Magic, Greek." In Oxford Classical Dictionary in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, April 2019. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/121 For more information, please contact [email protected]. magic, Greek Oxford Classical Dictionary magic, Greek Radcliffe G. Edmonds III Subject: Greek History and Historiography, Greek Myth and Religion Online Publication Date: Apr 2019 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8278 Summary and Keywords Greek magic is the discourse of magic within the ancient Greek world. Greek magic includes a range of practices, from malevolent curses to benevolent protections, from divinatory practices to alchemical procedures, but what is labelled magic depends on who is doing the labelling and the circumstances in which the label is applied. The discourse of magic pertains to non-normative ritualized activity, in which the deviation from the norm is most often marked in terms of the perceived efficacy of the act, the familiarity of the performance within the cultural tradition, the ends for which the act is performed, or the social location of the performer. -

Magic & Witchcraft in Africa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kohnert, Dirk Article — Accepted Manuscript (Postprint) Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa World Development Suggested Citation: Kohnert, Dirk (1996) : Magic and witchcraft: Implications for Democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa, World Development, ISSN 0305-750X, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 24, Iss. 8, pp. 1347-1355, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00045-9 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/118614 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Authors version – published in: World Development, vol. 24, No. 8, 1996, pp. 1347-1355 Magic and Witchcraft Implications for Democratization and Poverty-Alleviating Aid in Africa Dirk Kohnert 1) Abstract The belief in occult forces is still deeply rooted in many African societies, regardless of education, religion, and social class of the people concerned.