History and a Case for Prescience: Short Studies of Sylvia Plath's 1956 Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

The Denim Report

118 Fashion Forward Trends spring/summer 2016 | fabrics & more | FFT magazine 119 THE DENIM REPORT n this season, the denim offering is wide and qualitative: selvedge denim for purists, power stretch for trendsetters, washed-out effect for the 70s wind blowing around Ithe fashion world, and eco-friendly for green and ethical brands. Little did one know that the fabric would ingratiate itself in the mainstream so decidedly as to become the uniform of generations post the 80s. Irrespective of whether you belong in the 1% or the 99, your age bracket or your cultivated tastes, denim has been part of everyone’s wardrobe. It’s a 60 billion dollar market for retailers alone and designers are keen to partake a piece of this massive pie. It helps that the fabric is the ‘people pleaser’ – it will readily turn into anything one likes. Numerous innovations and fabric infusions such as khadi-denim, silk- denim, 3D textures and laser and ozone finishes change its face beyond comprehension, and this, once street-style, turns sophisticated enough to form a cocktail dress. INDUSTRY TRENDS Sustainability has been a long-standing buzzword but there is ever-newer growth in this direction. As the trend for distressed jeans diminishes, the dyeing process becomes less dependent on chemical sprays and resins. Multiple brands are opting to use 100% organic cotton and natural dye. Artisanal products go for untreated metal zippers and rivets, making it non-toxic. Chemical companies’ enthusiasm for change is making them to associate with leading jeans manufacturers to bring about major savings in key materials, energy, water usage, waste and emission reductions, and ensuring your right to operate in communities around the world. -

1988 the Witness, Vol. 71, No. 10. October 1988

VOLUME -71 NUMBER* 10 OCTOBER 1988 publication. Oand n the road reuse for again . required Permission DFMS. / Church Episcopal the of Archives 2020. The Rev. Barbara C. Harris, Executive Director Episcopal Church Publishing Company elected first woman bishop in the Anglican Communion Copyright The politics of intolerance • Manning Marable 'Last Temptation of Christ' • Paul Moore, Jr. Lambeth's new face • Barbara C. Harris • Susan E. Pierce Letters Maurice and Mosley ing classes were not yet ready to be which we can be sure. As such, his The rather moving testimony of Carter given the right to vote that the Chartists work for justice was flawed. But then, Heyward to Bishop J. Brooke Mosley in were demanding. Maurice and Com- so too was the splendid ministry of the May WITNESS employed a number pany defended the right to vote as a Brooke Mosley, and so is my own and, of metaphors and comparisons to illus- privilege that necessitated education I dare say, Professor Hood's as well. trate the several passions of the "bishop and superior intelligence because politi- Which is fine, as long as, in our own for all seasons," including one of the cal issues were so complex. historical moment, we are willing to 19th century Church of England social The misnomer "Christian socialism" build, gratefully and critically, on the thinker, Frederick Denison Maurice. actually comes from pamphlets and contributions of those who have gone The rhapsodic cadences of her attribute tracts written mostly by Maurice, begin- before — attempting to continue the publication. conveyed the continued myth about the ning with his Christian Socialism. -

Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eoN - Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Gaspa, Salvatore, "Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The eN o-Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Garments, Parts of Garments, and Textile Techniques in the Assyrian Terminology: The Neo- Assyrian Textile Lexicon in the 1st-Millennium BC Linguistic Context Salvatore Gaspa, University of Copenhagen In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Victor Mature ̘͙” ˪…˶€ (Ìž'í'ˆìœ¼ë¡Œ)

Victor Mature ì˜í ™” 명부 (작품으로) The Tartars https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-tartars-7768139/actors The Last Frontier https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-last-frontier-128975/actors Affair with a Stranger https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/affair-with-a-stranger-4688850/actors The Bandit of Zhobe https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-bandit-of-zhobe-7715528/actors Won Ton Ton, the Dog Who https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/won-ton-ton%2C-the-dog-who-saved-hollywood- Saved Hollywood 3569779/actors Captain Caution https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/captain-caution-331698/actors China Doll https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/china-doll-2963702/actors The Glory Brigade https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-glory-brigade-3644656/actors Every Little Crook and Nanny https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/every-little-crook-and-nanny-5417519/actors No, No, Nanette https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/no%2C-no%2C-nanette-3877427/actors Head https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/head-3280621/actors Kiss of Death https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kiss-of-death-1197547/actors Moss Rose https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/moss-rose-2084202/actors Firepower https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/firepower-3414366/actors Hannibal https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hannibal-1576167/actors Timbuktu https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/timbuktu-3531190/actors Interpol https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/interpol-6056379/actors The -

Dress Code Table

DRESS CODE FOR CONFERMENT CEREMONIES Wreathbinding Conferment Ceremony and Church Conferment and service or Secular Service Dinner and swordwhetting Ball day Masters, evening tail evening tail coat 1), black waistcoat, white evening tail gentlemen coat 1), white gloves, wreath and ring coat 1), white waistcoat waistcoat, white gloves, wreath and ring Masters, colourful, white, fulllength gown that is not white, ladies fulllength décolleté, white gloves and shoes, fulllength evening gown 2) wreath and ring 3) gown, white gloves and shoes, wreath and ring 5) Wreath evening tail evening tail coat 1), black waistcoat, white evening tail binders coat 1), white gloves coat 1), white waistcoat waistcoat, white gloves Wreath colourful, white, fulllength gown that is not White fulllength binderesses fulllength décolleté, white gloves and shoes 3) gown, white evening gown 2) gloves and shoes 5) Jubilee evening tail evening tail coat 1), black waistcoat, white evening tail masters, coat 1), white gloves, wreath and ring coat 1), white gentlemen waistcoat waistcoat, white gloves, wreath and ring Jubilee colourful, black, fulllength gown that is not black, masters, fulllength décolleté, black gloves and shoes, fulllength ladies evening gown 2) wreath and ring 4) gown, black gloves and shoes, wreath and ring 5) Jubilee evening tail evening tail coat 1), black waistcoat, white evening tail masters' coat 1), white gloves coat 1), white wreath waistcoat waistcoat, white binders gloves Jubilee colourful, black, fulllength gown that is not -

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred

From Synthespian to Convergence Character: Reframing the Digital Human in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema by Jessica L. Aldred A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2012 Jessica L. Aldred Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94206-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Acropolis Statues Begin Transfer to New Home Christodoulos Now

O C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek Americans A WEEKLY GREEK AMERICAN PUBLICATION c v www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 11, ISSUE 523 October 20, 2007 $1.00 GREECE: 1.75 EURO Acropolis Statues Begin Transfer to New Home More than 300 Ancient Objects will be Moved to New Museum Over the Next Four Months By Mark Frangos Special to the National Herald ATHENS — Three giant cranes be- gan the painstaking task Sunday, October 14 of transferring hun- dreds of iconic statues and friezes from the Acropolis to an ultra-mod- ern museum located below the an- cient Athens landmark. The operation started with the transfer of part of the frieze at the northern end of the Parthenon. That fragment alone weighed 2.3 tons and in the months to come, the cranes will move objects as heavy as 2.5 tons. Packed in a metal casing the frieze, which shows a ancient reli- gious festival in honor of the god- dess Athena, was transferred from the old museum next to the Parthenon to the new one 984 feet below. Under a cloudy sky, with winds AP PHOTO/THANASSIS STAVRAKIS of 19 to 24 miles an hour, the three Acropolis Museum cranes passed the package down to its new home, in an operation that "Everything passed off well, de- lasted one and a half hours. spite the wind," Zambas told AFP. Following the operation on site Most of the more than 300 more AP PHOTO/THANASSIS STAVRAKIS was Culture Minister Michalis Li- ancient objects should be trans- A crane moves a 2.3-ton marble block part of the Parthenon frieze to the new Acropolis museum as people watch the operation in Athens on Sunday, apis, who also attended Thursday's ferred over the next four months, October 14, 2007. -

Pope Protests Expulsion of Archbishop by Haiti

THE VOICE HOI Blseayn* Blvd., Miami 3», tim. Return Pottage Guaranteed VOICE Weekly Publication of the Diocese of Miami Covering the 16 Counties of South Florida VOL II, NO. 37 Price $5 a year ... 15 cents a copy DEC. 2, 1960 Pope Protests Expulsion Of Archbishop By Haiti The Holy See has deplored Prince as he sat in his study purple sash and carried only the unjust and disrespectful by six uniformed gendarmes the passport and an airways treatment given to Archbishop and six members of the secret ticket to Paris which"had been Francois Poirier of Port au police. He was placed immedi- handed to him. ately aboard a plane for Mi- Prince by the Haitian govern- The 56-year-old prelate was ami with no personal effects ment when it expelled him met at the Miami International from Haiti on Thanksgiving Day and no money. Airport by Bishop Coleman F. last week. He wore his white robe with (Continued on Page 13) The Vatican expressed its grief in a telegram sent to the Archbishop in the name of Pope John XXIII by Dom- enico Cardinal Tardini, Vati- can Secretary of State. The wire was sent to Archbishop Poirier in his native France to which he returned after first landing in Miami on his forced flight into exile. The telegram said Pope John "is deeply grieved by the vio- lation of the holy rights of the BANISHED FROM HAITI, Archbishop Francois erck Wass, assistant chancellor, after forced Church." It expressed the Poirier is met at Miami's International Airport flight from Port au Prince. -

COA Template

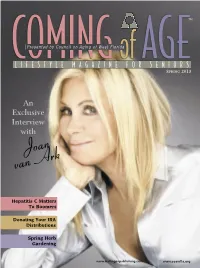

TM COMINGPresented by Council on Aging of West Floridaof AGE LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE FOR SENIORS SPRING 2013 An Exclusive Interview with Joan van Ark Hepatitis C Matters To Boomers Donating Your IRA Distributions Spring Herb Gardening www.ballingerpublishing.com www.coawfla.org COMMUNICATIONS CORNER Jeff Nall, APR, CPRC Editor-in-Chief The groundhog did not see his shadow and we’ve “sprung our clocks forward,” so now it is time to get out and enjoy the many outdoor activities that our area has to offer. Some of my favorites are the free outdoor concerts such as JazzFest, Christopher’s Concerts and Bands on the Beach. I tend to run into many of our readers at these events, but if you haven’t been, check out page 40. For another outdoor option for those with more of a green thumb, check out our article on page 15, which has useful tips for planting an herb garden. This issue also contains important information for baby boomers about Readers’ Services hepatitis C. According to the Centers for Disease Control, people born from Subscriptions Your subscription to Coming of Age 1945 through 1965 account for more than 75 percent of American adults comes automatically with your living with the disease and most do not know they have it. In terms of membership to Council on Aging of financial health, our finance article on page 18 explains how qualified West Florida. If you have questions about your subscription, call Jeff charitable distributions (QCDs) from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) Nall at (850) 432-1475 ext. 130 or are attractive to some investors because QCDs can be used to satisfy required email [email protected]. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.