Starmakers: Dictators, Songwriters, and the Negotiation of Censorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rádio, Ditadura E Rock Radio, Dictatorship and Rock

Rádio, ditadura e rock 2 Sergio Ricardo Quiroga 2 6 Como citar este artigo: QUIROGA, Sergio Ricardo. Radio, Dictatorship and rock. Revista Rádio-Leituras, Mariana-MG, v. 07, n. 01, pp. 226-241, jan./jun. 2016. Radio, Dictatorship and rock Sergio Ricardo Quiroga1 Recebido em: 02 de fevereiro de 2016. Aprovado em: 11 de junho de 2016. Resumo Este artigo descreve o desempenho de dois programas de rádio na Rádio LV 15 Rádio Villa Mercedes, San Luís, Argentina, em 1982-1983, os dois últimos anos de um período triste da história da Argentina chamado "Processo de Reorganização Nacional" entre 1976 e 1983. Os programas "Pessoas jovens" e “LV Amizade”, emitidos pela LV 15 Rádio Villa Mercedes (S.L.), aos sábados, durante 1982 e 1983 e foram dedicados à juventude. Após a Guerra das Malvinas e a proibição de radiodifusão argentina na música estrangeira, os clássicos esquecidos do rock argentino começaram a formar o ingrediente principal do programa. Anteriormente, a ditadura militar reprimiu toda a atividade política, instalando as "listas de artistas proibidos" que não podiam ser divulgados através da mídia. Palavras-chave: rádio; rock; ditadura 1 Cátedra Libre Pensamiento Comunicacional Latinoamericano - ICAES. Integrante colaborador Proyecto Cambios y Tensiones en la Universidad Argentina en el marco del centenario de la Reforma de 1918. Vol 7, Num 01 Edição Janeiro – Junho 2016 ISSN: 2179-6033 http://www.periodicos.ufop.br/pp/index.php/radio-leituras Abstract This paper describes the performance of two radio programs on Radio LV 15 Radio Villa Mercedes, San Luis, Argentina, in 1982-1983, the last two years of a sad period in Argentina's history called "National Reorganization Process" between 1976 and 1983. -

Rock Nacional” and Revolutionary Politics: the Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976

“Rock Nacional” and Revolutionary Politics: The Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976 Valeria Manzano The Americas, Volume 70, Number 3, January 2014, pp. 393-427 (Article) Published by The Academy of American Franciscan History DOI: 10.1353/tam.2014.0030 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/tam/summary/v070/70.3.manzano.html Access provided by Chicago Library (10 Feb 2014 08:01 GMT) T HE A MERICAS 70:3/January 2014/393–427 COPYRIGHT BY THE ACADEMY OF AMERICAN FRANCISCAN HISTORY “ROCK NACIONAL” AND REVOLUTIONARY POLITICS: The Making of a Youth Culture of Contestation in Argentina, 1966–1976 n March 30, 1973, three weeks after Héctor Cámpora won the first presidential elections in which candidates on a Peronist ticket could Orun since 1955, rock producer Jorge Álvarez, himself a sympathizer of left-wing Peronism, carried out a peculiar celebration. Convinced that Cám- pora’s triumph had been propelled by young people’s zeal—as expressed in their increasing affiliation with the Juventud Peronista (Peronist Youth, or JP), an organization linked to the Montoneros—he convened a rock festival, at which the most prominent bands and singers of what journalists had begun to dub rock nacional went onstage. Among them were La Pesada del Rock- ’n’Roll, the duo Sui Géneris, and Luis Alberto Spinetta with Pescado Rabioso. In spite of the rain, 20,000 people attended the “Festival of Liberation,” mostly “muchachos from every working- and middle-class corner of Buenos Aires,” as one journalist depicted them, also noting that while the JP tried to raise chants from the audience, the “boys” acted as if they were “untouched by the political overtones of the festival.”1 Rather atypical, this event was nonetheless significant. -

Music and Spiritual Feminism: Religious Concepts and Aesthetics

Music and spiritual feminism: Religious concepts and aesthe� cs in recent musical proposals by women ar� sts. MERCEDES LISKA PhD in Social Sciences at University of Buenos Aires. Researcher at CONICET (National Council of Scientifi c and Technical Research). Also works at Gino Germani´s Institute (UBA) and teaches at the Communication Sciences Volume 38 Graduation Program at UBA, and at the Manuel de Falla Conservatory as well. issue 1 / 2019 Email: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9692-6446 Contracampo e-ISSN 2238-2577 Niterói (RJ), 38 (1) abr/2019-jul/2019 Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication is a quarterly publication of the Graduate Programme in Communication Studies (PPGCOM) at Fluminense Federal University (UFF). It aims to contribute to critical refl ection within the fi eld of Media Studies, being a space for dissemination of research and scientifi c thought. TO REFERENCE THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE USE THE FOLLOWING CITATION: Liska, M. (2019). Music and spiritual feminism. Religious concepts and aesthetics in recent musical proposals by women artists. Contracampo – Brazilian Journal of Communication, 38 (1). Submitted on: 03/11/2019 / Accepted on: 04/23/2019 DOI – http://dx.doi.org/10.22409/contracampo.v38i1.28214 Abstract The spiritual feminism appears in the proposal of diverse women artists of Latin American popular music created recently. References linked to personal and social growth and well-being, to energy balance and the ancestral feminine powers, that are manifested in the poetic and thematic language of songs, in the visual, audiovisual and performative composition of the recitals. A set of multi religious representations present in diff erent musical aesthetics contribute to visualize female powers silenced by the patriarchal system. -

Grilla De Horarios De Estudio Urbano

GRILLA DE HORARIOS DE ESTUDIO URBANO LUNES 18 a 20 hs. - CURSO BÁSICO DE PROTOOLS | Francisco Rojas | 5 de mayo 18 a 20 hs. - EDICIÓN INDEPENDIENTE DE DISCOS | Fabio Suárez | 19 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - CIRCULACIÓN DE MÚSICA POR LA WEB | Matías Erroz | 19 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - CANTO EN EL ROCK | María Rosa Yorio | 5 de mayo 20 a 22 hs. - ARTE Y TECNOLOGÍA MULTIMEDIA | Alejandra Isler | 19 de mayo MARTES 19 a 21 hs. - INTRO A DJ | Carlos Ruiz y Ramón Gallo (Adisc) | 6 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - ARTE DE TAPA DE DISCOS | Ezequiel Black | 29 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - VIAJE POR LA MENTE DE LOS GENIOS DEL ROCK | Pipo Lernoud | 29 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - ARREGLOS Y COMPOSICIÓN EN LA MÚSICA POPULAR | Pollo Raffo | comienza en junio, al finalizar el ciclo de Pipo Lernoud MIÉRCOLES 17 a 19 hs. - TALLER LITERARIO | Ariel Bermani | 30 de abril 17 a 19 hs. - TALLER DE GRABACIÓN | Mariano Ondarts | 30 de abril 18 a 20 hs. - PERIODISMO Y ROCK | Matías Capelli | 7 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - ABLETON LIVE | Eduardo Sormani | 30 de abril 19 a 21 hs. - REASON | Eduardo Sormani | comienza en junio, al finalizar el curso de Ableton Live 19 a 21 hs. - COMUNICACIÓN Y MANAGEMENT DE PROYECTOS MUSICALES | Leandro Frías | 30 de abril JUEVES 17 a 19 hs. - SONIDO EN VIVO | Pablo González Martínez | 8 de mayo 17:30 a 19:30 hs. - LA CÁMARA POR ASALTO | Pablo Klappenbach | 8 de mayo 19 a 21 hs. - REVOLUCIÓN DEL ROCK | Alfredo Rosso | 8 de mayo 19:30 a 21:30 hs. -

Escúchame, Alúmbrame. Apuntes Sobre El Canon De “La Música Joven”

ISSN Escúchame, alúmbrame. 0329-2142 Apuntes de Apuntes sobre el canon de “la investigación del CECYP música joven” argentina entre 2015. Año XVII. 1966 y 1973 Nº 25. pp. 11-25. Recibido: 20/03/2015. Aceptado: 5/05/2015. Sergio Pujol* Tema central: Rock I. No caben dudas de que estamos viviendo un tiempo de fuerte interroga- ción sobre el pasado de lo que alguna vez se llamó “la música joven ar- gentina”. Esa música ya no es joven si, apelando a la metáfora biológica y más allá de las edades de sus oyentes, la pensamos como género desarro- llado en el tiempo según etapas de crecimiento y maduración autónomas. Veámoslo de esta manera: entre el primer éxito de Los Gatos y el segundo CD de Acorazado Potemkin ha transcurrido la misma cantidad de años que la que separa la grabación de “Mi noche triste” por Carlos Gardel y el debut del quinteto de Astor Piazzolla. ¿Es mucho, no? En 2013 la revista Rolling Stone edición argentina dedicó un número es- pecial –no fue el primero– a los 100 mejores discos del rock nacional, en un arco que iba de 1967 a 2009. Entre los primeros 20 seleccionados, 9 fueron grabados antes de 1983, el año del regreso de la democracia. Esto revela que, en el imaginario de la cultura rock, el núcleo duro de su obra apuntes precede la época de mayor crecimiento comercial. Esto afirmaría la idea CECYP de una época heroica y proactiva, expurgada de intereses económicos e ideológicamente sostenida en el anticonformismo de la contracultura es- tadounidense adaptada al contexto argentino. -

Charly García

Charly García ‘El Prócer Oculto’ [Un relato a través de entrevistas a Sergio Marchi y Alfredo Rosso] Alumna: Laura Impellizzeri ‘Charly García: El Prócer Oculto’ Comunicación Social - UNLP 2017 Directora: Prof. Mónica Caballero Agradecimientos. La última etapa de la carrera es la elaboración del T.I.F. [Trabajo Integrador Final] que lleva tiempo, dedicación, ganas y esfuerzo. Por supuesto que estos elementos no confluyen siempre; no están de forma permanente ni simultánea. En esos ‘lapsus’ de cansancio, de tener la mente en blanco porque no hay ideas que plasmar, aparecen los estímulos, las ayudas extra-académicas que nos dan el aliento necesario para seguir adelante. En mi caso, necesito agradecer profundamente a los dos pilares de mi vida que son mi madre Julia y mi padre Miguel, quienes, además de darme educación y amor desde que nací, me han dado la seguridad, la confianza y el apoyo incondicional en cada paso que di y doy en mi carrera. También agradezco a mi hermana Marta por haberme acercado, de alguna forma, a Charly García. No pueden faltar mis amigos. Estuvieron ahí ante las permanentes caídas y el enojo conmigo misma por la poca creatividad que a veces tengo. Gracias por el amor y el empuje que recibo desde siempre y de forma permanente. A mi amigo y colega Lucio Mansilla, a quien admiro en todo sentido, y que estuvo permanentemente a mi lado, ayudándome activa y espiritualmente. A mi directora de tesis, la Lic. Mónica Caballero, que la elegí como tal no sólo porque la respeto como docente, sino también por su compromiso profesional y personal. -

0A7aa945006f6e9505e36c8321

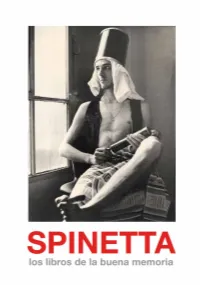

2 4 Spinetta. Los libros de la buena memoria es un homenaje a Luis Alberto Spinetta, músico y poeta genial. La exposición aúna testimonios de la vida y obra del artista. Incluye un conjunto de manuscritos inéditos, entre los que se hallan poesías, dibujos, letras de canciones, y hasta las indicaciones que le envió a un luthier para la construcción de una guitarra eléctrica. Se exhibe a su vez un vasto registro fotográfico con imágenes privadas y profesionales, documentales y artísticas. Este catálogo concluye con la presentación de su discografía completa y la imagen de tapa de su único libro de poemas publicado, Guitarra negra. Se incluyen también dos escritos compuestos especialmente para la ocasión, “Libélulas y pimientos” de Eduardo Berti y “Eternidad: lo tremendo” de Horacio González. 5 6 Pensé que habías salido de viaje acompañado de tu sombra silbando hablando con el sí mismo por atrás de la llovizna... Luis Alberto Spinetta, Guitarra negra,1978 Niño gaucho. 23 de enero de 1958 7 Spinetta. Santa Fe, 1974. Fotografía: Eduardo Martí 8 Eternidad: lo tremendo por Horacio González Llamaban la atención sus énfasis, aunque sus hipérboles eran dichas en tono hu- morístico. Quizás todo exceso, toda ponderación, es un rasgo de humor, un saludo a lo que desearíamos del mundo antes que la forma real en que el mundo se nos da. Había un extraño recitado en su forma de hablar, pero es lógico: también en su forma de cantar, siempre con una resolución final cercana a la desesperación. Un plañido retenido, insinuado apenas, pero siempre presente. ¿Pero lo definimos bien de este modo? ¿No es todo el rock, “el rock del bueno”, como decía Fogwill, completamente así? Quizás esa cauta desesperación de fondo precisaba de un fraseo que recubría todo de un lamento, con un cosquilleo gracioso. -

El Cine Es Un Tópico Con Una Importante Presencia En Las

CANÇÕES, FILMES E DIVAS DE PUBIS ANGELICAL NA MÚSICA DE CHARLY GARCIA (1972-1982) Julio Ogas1 Resumo: Na primeira etapa da produção de Charly Garcia o cinema tem um papel destacado. Várias canções soltas, um disco temático e a musicalização de duas películas constituem claros indícios nesse sentido. O espaço de significação que se abre a partir desse tema permite apreciar algumas das idéias que prevalecem na proposta do autor. Tanto a linguagem literal como a simbólica se conjugam para transmitir uma mensagem de mudança sob medida do ser humano, mas profundamente implicado no entorno social de sua época. Palavras-chave: música popular, cinema, Charly García Abstract: In the first stage of Charly García‟s production, the cinema plays an important role. Several single songs, a thematic record and the music of two films are clear indications in this regard. The meaning space that opens from this subject allows appreciating some ideas that prevail in the author's proposal. Both the literal and the symbolic languages combine to convey a message of change to man extent but deeply involved in the social environment of his time. Keywords: popular music, film, Charly García O cinema constitui uma temática recorrente na ampla produção de Carlos Alberto Garcia Moreno (1951), Charly García. Na discografia produzida entre 1972 e 1982, através de seus três conjuntos estáveis, Sui Generis, La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros e Seru Giran, encontra-se refletida a presença desse tema em títulos como: Las increíbles aventuras del Sr. Tijeras, Marylin la cenicienta y las mujeres, Qué se puede hacer (salvo ver películas), Canción de Hollywood o Cinema Verité, entre outros. -

TANGO… the Perfect Vehicle the Dialogues and Sociocultural Circumstances Informing the Emergence and Evolution of Tango Expressions in Paris Since the Late 1970S

TANGO… The Perfect Vehicle The dialogues and sociocultural circumstances informing the emergence and evolution of tango expressions in Paris since the late 1970s. Alberto Munarriz A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO March 2015 © Alberto Munarriz, 2015 i Abstract This dissertation examines the various dialogues that have shaped the evolution of contemporary tango variants in Paris since the late 1970s. I focus primarily on the work of a number of Argentine composers who went into political exile in the late 1970s and who continue to live abroad. Drawing on the ideas of Russian linguist Mikhail Bakhtin (concepts of dialogic relationships and polyvocality), I explore the creative mechanisms that allowed these and other artists to engage with a multiplicity of seemingly irreconcilable idioms within the framing concept of tango in order to accommodate their own musical needs and inquietudes. In addition, based on fieldwork conducted in Basel, Berlin, Buenos Aires, Gerona, Paris, and Rotterdam, I examine the mechanism through which musicians (some experienced tango players with longstanding ties with the genre, others young performers who have only recently fully embraced tango) engage with these new forms in order to revisit, create or reconstruct a sense of personal or communal identity through their performances and compositions. I argue that these novel expressions are recognized as tango not because of their melodies, harmonies or rhythmic patterns, but because of the ways these features are “musicalized” by the performers. I also argue that it is due to both the musical heterogeneity that shaped early tango expressions in Argentina and the primacy of performance practices in shaping the genre’s sound that contemporary artists have been able to approach tango as a vehicle capable of accommodating the new musical identities resulting from their socially diverse and diasporic realities. -

Pdf?Sequence=1&Isallowed=Y> (22 Dec

Civitas - Revista de Ciências Sociais ISSN: 1519-6089 ISSN: 1984-7289 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul Boix, Ornela New uses of music: An analysis based on indie music in Buenos Aires Civitas - Revista de Ciências Sociais, vol. 19, no. 1, 2019, January-April, pp. 230-246 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul DOI: https://doi.org/10.15448/1984-7289.2019.1.30121 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=74260188014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1984-7289.2019.1.30121 Articles New uses of music An analysis based on indie music in Buenos Aires Novos usos da música Uma análise baseada na música indie em Buenos Aires Nuevos usos de la música Un análisis basado en la música indie de Buenos Aires iD Ornela Boix1 Abstract: During the 2000s, the term “indie” became common and relatively principal for the juvenile, urban music of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires. How can we understand the indie phenomenon in the history of juvenile music related to Argentine rock bands? What variables should we take into consideration to comprehend indie since its logic differs from the one established by the identitarian appropriation of music genres? In order to answer these questions, we describe indie music in Buenos Aires and show its evolution. -

Download File

Reinterpreting the Global, Rearticulating the Local: Nueva Música Colombiana, Networks, Circulation, and Affect Simón Calle Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Simón Calle All rights reserved ABSTRACT Reinterpreting the Global, Rearticulating the Local: Nueva Música Colombiana, Networks, Circulation, and Affect Simón Calle This dissertation analyses identity formation through music among contemporary Colombian musicians. The work focuses on the emergence of musical fusions in Bogotá, which participant musicians and Colombian media have called “nueva música Colombiana” (new Colombian music). The term describes the work of bands that assimilate and transform North-American music genres such as jazz, rock, and hip-hop, and blend them with music historically associated with Afro-Colombian communities such as cumbia and currulao, to produce several popular and experimental musical styles. In the last decade, these new fusions have begun circulating outside Bogotá, becoming the distinctive sound of young Colombia domestically and internationally. The dissertation focuses on questions of musical circulation, affect, and taste as a means for articulating difference, working on the self, and generating attachments others and therefore social bonds and communities This dissertation considers musical fusion from an ontological perspective influenced by actor-network, non-representational, and assemblage theory. Such theories consider a fluid social world, which emerges from the web of associations between heterogeneous human and material entities. The dissertation traces the actions, interactions, and mediations between places, people, institutions, and recordings that enable the emergence of new Colombian music. In considering those associations, it places close attention to the affective relationships between people and music. -

WOP SONG: TUNE & ECHO a Stage Play with Music Written by Vian Andrews Italian Translation by Claudio Ginocchietti Fourth

WOP SONG: TUNE & ECHO A Stage Play with Music Written by Vian Andrews Italian translation by Claudio Ginocchietti Fourth Revision completed 10 Feb '17 Based on an original idea Copyright October 2016 Vian Andrews 4583 Neville Street Burnaby, BC V5J 3G9 778-378-7954 WOPSONG: TUNE & ECHO ACT 1 A sunny piazza in the dilapidated, dun-colored village of Calabro in the mountains of southern Italy, 2016. On the left, the main door to the village church, on the right a cafe whose sign is badly in need of repainting, with two tables with chairs. In between the church and the cafe there is a row of three drab houses. On the first house and third house a shutter or two is open, but the shutters of the center house are closed and one or two are hanging askew. A small riser stands in front of the center house. Two older men play cards at one of the cafe tables. An old woman, dressed in black, sits on the stoop of the first house, taking in the scene while absentmindedly gnashing her teeth. Suddenly the blast of a horn from an arriving bus is heard off left, making the old woman and the men jump. Father Sarducci, the town priest opens the door of the church and steps out at the same time, Gaetano, the owner of the cafe and his wife, Giuseppina, step out of the cafe to find out what is going on. The voices of three men singing Bon Jovi’s This House is Not for Sale is heard coming from the direction of the bus.