Best Practices in Omnichannel Customer Experience Design for Luxury Retail Consumers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Affaire Carvalho : Un an Ferme Pour L'ex-Associé De Romeyer

ASSE PAGE 22 Affaire Carvalho : un an ferme pour l’ex-associé de Romeyer 136546800 Vendredi 8mars • 20h Soirée des femmes Soirée dansante & Spectacle chorégraphique Buffets et boissons Réservations àl’Escargot d’Or AVOLONTÉ 40 € 04 77 41 24 04 Édition Saint-Étienne 42G Mercredi 20 février 2019 - 1,10 € LUCKY Imprimerie • 04 77 36 77 65 • ST CYPRIEN • Ne pas jeter sur la voie publique TENTATIVE DE SUICIDE À SAINT-ÉTIENNE Claude Borrel n’a écouté que son courage pour porter secours à une jeune femme de 22 ans qui menaçait d’en finir. Photo LE PROGRÈS / Sonia BARCET PAGE 9 FRANCE SAINT-ÉTIENNE / TARENTAIZE Sept mois après le Micros dans les début de l’affaire, rues : une législation Alexandre Benalla encadrée mais… placé en détention provisoire PAGE 13 La violation de la vie privée en question. Photo Josette GENTE PAGE 6 SAINT-ÉTIENNE ÀDÉCOUVRIR Salon de la pêche à la sans modération mouche ce week-end Lesbonsconseils pour choisir, conserveretdégusterson vin. CONSEILS PRATIQUES ET ACCESSOIRES ACCORD METS/ VIN 148 VINS SÉLECTIONNÉS VOTREMAGAZINEDE230 PAGES EN VENTE CHEZ VOV O TRT R EME M ARA R CHC H AANDN D DED E JOURJ O U R NAN A UXU X -88 €5€ 5 0 . Photo LE PROGRÈS / Philippe TRIAS L’abus d’alcool est dangereux pour la santé,consommez avec modération 134798700 PAGE 32 2 ACTU LE FAIT DU JOUR SOCIÉTÉ Le « Kaiser » de la haute couture s’est éteint à 85 ans Karl Lagerfeld, grand crêpe noir sur la mode Le directeur artistique de la maison Chanel est mort mardi à l’Hôpital américain de Neuilly où il avait été admis en urgence } lundi soir. -

Welcome to Madrid

Welcome to Madrid Bold and revolutionary, this designer dared to “masculinise” the female wardrobe, introducing suits or knitwear –until then exclusively used for men- to provide an escape for women from the attire of the 20th century. The legendary Coco Chanel was ahead of her time, envisioning a free and independent woman, in need, above all, of comfortable garments. Chanel’s pieces are as mythical as their creator: the rimmed tweed jacket, the beige sling-back with black toecap or the eternal perfume Chanel Nº5. Her boutiques all over the world display her tradition and legacy, including the one on calle Ortega y Gasset, where harmony and minimalism come together to create a spaciousness that grants life to the creations. The label’s spacious Madrid store is 450 m2 in size, spread over three floors, where you can find fashion, glasses, perfumes and beauty products, watches, and jewellery. Since 1983, haute couture and prêt à porter under the double C brand come from the hand of Karl Lagerfeld who, as rebellious as his predecessor, reinvents and refreshes with each collection the spirit of the former, yet immortal, “Mademoiselle Chanel”. When the designer died in 2019, Virginie Viard, Lagerfeld’s right hand for more than 30 years, took over his post. Interest data Address Tourist area Calle de Jose Ortega y Gasset, 16 28006 Barrio de Salamanca Telephone Web (+34) 91 431 30 36 http://www.chanel.com Metro Bus Núñez de Balboa (L5, L9), Serrano (L4), 1, 5, 9, 14, 19, 27, 45, 51, 74, 150 Velázquez (L4) Cercanías (Local train) Type Madrid-Recoletos Moda Opening times Mon – Sat: 11:00am –7:00pm. -

Lifestyle Fashion Thursday, March 5, 2020

Established 1961 21 Lifestyle Fashion Thursday, March 5, 2020 hanel designer Virginie Viard house founded by the horse- and polo- CTuesday signaled she may put an mad Gabrielle Chanel, with slashed jodh- end to the brand’s themed Paris purs, folded down calf-length musketeer fashion week spectaculars, a year after the boots and billowing side-buttoned leather death of her legendary predecessor Karl trousers that resembled riding chaps and Lagerfeld. The German showman spent black suede jockey hats. Skirts were also millions turning the vast Grand Palais into slashed, sometimes up to the hip with his playground, building a Chanel space Viard saying she was after movement, rocket, a near life-sized ocean liner, the “freedom, energy and absolute desire”. Her Eiffel Tower, a tropical beach and the big innovation was putting snap buttons on Verdun gorges-complete with waterfalls- Chanel jackets for the first time, to free up as a backdrop for his extravagant shows. the wearer and allow “a more lively ges- ture”, she said. ‘Feminine Amazons’ Models present creations for Chanel during the Women’s Viard said the equestrian theme was Fall-Winter 2020-2021 Ready-to-Wear collection fashion also partly inspired by a photo of show in Paris. — AFP photos Lagerfeld in a striped suit and riding boots. But she also drew ideas from Claude Chabrol’s French film classic, the 1968 chiller “Les Biches”, about a love triangle. Indeed the show began with a nod to the movie, with two typically chic Parisian friends walking arm in arm, “as feminine as they were Amazons”, Viard insisted. -

Chanel X Paris Opera Opening Gala: An

CHANEL X PARIS OPERA OPENING GALA: AN ARTFUL PAIRING FOR THE ELITE Gabrielle Chanel’s love for the arts is an inextricable part of the house’s history. As a friend and patron of Serge Diaghilev, the founder of the Ballets Russes company, she had always believed in the ability of classical dance to transform into a well- rounded and modern power that could combine different sorts of expression into one. Music, visual arts and dance are all particles of a greater aesthetic force, the source of original inspiration. Karl Lagerfeld’s love for ballet too, along with his collaborations with emblematic choreographers as a costume designer are indicative of the brand’s dedication to the ideals and cultural significance of dance. Being one of the most prestigious and exciting events chic and arty Parisians tend to look forward to, this year’s Paris Opera Ballet Gala came as a bummer to many due to its digital nature. Yet, even in the darkest of times, art finds the way to bring people together in awe-inspiring moments, no matter the medium and the proximity. For the Grand Pas Classique, a dance invented by choreographer Victor Gsovsky, Virginie Viard came up with two magnificent designs, crafted in an intricate fashion that creates the illusion of a dark night sky. Rich textures, a velvet blue leotard and a tutu embroidered with stars and constellations by Maison Lesage, infused the act with a sense of luxurious practicality that graced the dancers’ moves with plasticity and elegance. Dance and couture, two separate forms of creativity that intertwine to prove that true magic lies in carefully curated mixtures. -

Page 1.Qxp Layout 1

FREE Established 1961 Friday ISSUE NO: 18003 RABIA ALTHANI 9, 1441 AH FRIDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2019 Almost expired market: A Iraq revolution dramatized, Bahrain beat Iraq 7-5 on 6 place to bag a great deal 27 written, read, and painted 47 penalties after 2-2 draw Arson suspected as inferno guts electronics warehouse SEE PAGE 9 2 Friday Local Friday, December 6, 2019 Health on wheels PHOTO OF THE DAY Local Spotlight By Muna Al-Fuzai [email protected] isability is any deficiency in the physical, mental or sensory abilities of the individual, and it takes many Dforms, such as mental, hearing or visual or physical impairment. Last week the Kuwait Society for Human Rights carried out a humanitarian activity on the occasion of the International Day of Disabled Persons, which falls on Dec 3 every year. The event included sitting in a wheelchair and touring the venue to experience firsthand the suffering of people with disabilities and live their reality and the diffi- culties they face. The importance of this activity is that it sends clear and targeted messages about the role of the community and its members towards people with disabilities that force them to use wheelchairs, and that they are no less or different. I agree with these campaigns because I believe that in Kuwait people who use wheelchairs suffer a lot, whether due to disabilities or old age, especially when moving from one place to another, as not all places are equipped with wheelchair ramps. Worse, some healthy people use the parking spaces for disabled people, or ATM machines in some local banks that are allocated for people on wheelchairs. -

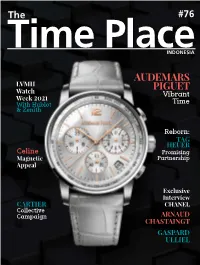

Audemars Piguet Collection

#76 AUDEMARS LVMH PIGUET Watch Vibrant Week 2021 With Hublot Time & Zenith CHANEL Reborn: TAG HEUER Celine Promising Magnetic Partnership Appeal Exclusive Interview CARTIER CHANEL Collective Campaign ARNAUD CHASTAINGT GASPARD ULLIEL WELCOME NOTE t has been a year since the onset of the pandemic and we are truly grateful for your continued support. For our first issue in 2021, we are highlighting the colourful timepieces of the Code 11.59 by Audemars Piguet collection. IOn our cover is the light grey Selfwinding Chronograph variant, a timepiece that is steeped in the manufacture’s savoir faire and forward-thinking spirit. Find out about the Code 11.59 by Audemars Piguet collection in our cover story, “Colourful Symphony.” In Industry News, we put the spotlight on the latest releases presented by Hublot and Zenith at the LVMH Watch Week 2021 held last January, as well as Cartier’s new international campaign showcasing its iconic designs. Speaking of experiences, Arnaud Chastaingt, Director of the CHANEL Watchmaking Creation Studio, and Gaspard Ulliel, Face of the “Monsieur” watch by CHANEL HORLOGERIE, share their thoughts and dreams from 20 years ago as part of the 20th anniversary celebration of the CHANEL J12 in our Interview section. In Reborn, we trace the parallel histories of TAG Heuer and Porsche in motorsports and racing, which led to the cementing of their ties this year. Discover the details of their partnership, as well as their first collaborative product, the TAG Heuer Carrera Porsche Chronograph, in “Authentic Alliance.” Despite the limitations brought about by the pandemic, the different luxury brands under Time International have each found a way to present their latest offerings in style. -

P20-21 Layout 1

20 Established 1961 Lifestyle Fashion Thursday, February 21, 2019 Designer Karl Lagerfeld to be cremated without ceremony arl Lagerfeld will be cremated without ceremony and his ashes are likely to be scattered with those of his mother and lover, his label said yesterday. “His wish- Kes will be respected,” a spokeswoman for his Karl Lagerfeld brand told AFP a day after the leg- endary designer died at the age of 85. The “Kaiser”-who was known for his rapier wit-had long insisted that he would “rather die” than be buried. “I’ve asked to be cremated and for my ash- es to dispersed with those of my mother... and those of Choupette (his cat), if she dies before me,” he said in one of his last major interviews. Lagerfeld had previously said that his ashes would be mixed with those of his longtime lover, the French dandy Jacques de Bascher, who died of AIDS in 1989. He told de Bascher’s biographer Marie Ottavi that he had kept half of his ashes so they be together again at the end. The German- born creator had put them away “somewhere secret. One day they will be added to mine,” he told Ottavi. Lagerfeld fell for the dashing de Bascher when he was 19 and looked after him until his death at 38. This was despite de Bascher, a notoriously philandering party animal, having an affair with Lagerfeld’s great rival Yves Saint Laurent. The other half of de Bascher’s ashes was given to his family, the French daily Le Monde reported yesterday. -

Kuwaittimes 5-5-2019.Qxp Layout 1

SHAABAN 30, 1440 AH SUNDAY, MAY 5, 2019 28 Pages Max 38º Min 24º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17824 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Israel, the only obstacle to Major disaster averted China ‘putting Muslims 9-man Spurs stunned; Elliott 5 WMD-free Mideast: Kuwait 6 as Fani hits Bangladesh 24 in concentration camps’ 28 becomes EPL youngest player Gaza-Israel hostilities flare up with rocket attacks, air strikes Violence up before Ramadan, Independence Day, Eurovision GAZA: Gaza militants fired dozens of rockets into Israel yesterday, drawing a wave of Israeli air strikes that Amir congratulates killed one Palestinian gunman, as hostilities flared across the border for a second day. The escalation began on citizens, residents Friday, when two Israeli soldiers were wounded by Gaza gunfire near the border. A retaliatory Israeli air strike killed two militants from the Islamist Hamas group that on Holy Ramadan governs Gaza. Two other Palestinians protesting near KUWAIT: His Highness the frontier were also killed by Israeli forces. Yesterday, the Amir Sheikh Sabah Israel hit Gaza with air strikes and tank fire after Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al- Palestinian militants fired about 150 rockets toward Sabah congratulated the Israeli cities and villages. Kuwaiti citizens and resi- The Israeli military said its forces had carried out dents on the advent of attacks against more than 30 targets belonging to the Holy Month of Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad militant group. A Ramadan the Amiri small armed pro-Hamas group in Gaza, The Protectors Diwan said yesterday. His of Al-Aqsa, said one of its men was killed in an air strike Highness the Amir, along yesterday. -

Storytelling As a Marketing Tool. Case Study: Chanel

Irina Guseva Storytelling as a marketing tool. Case Study: Chanel Case Chane Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and logistics Bachelor’s Thesis Date 30 April 2021 Abstract Author Irina Guseva Title Storytelling as a marketing tool: case Chanel. Number of Pages 57 pages + 2 appendices Date 30 April 2021 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor/Tutor John Greene, Lecturer The purpose of this study was to indicate how storytelling influences consumers of the luxury brand Chanel. Storytelling is a marketing tool that tells the story about the brand in order to attract and retain customers, enhance brand awareness and consumer loyalty. Chanel is a luxury fashion brand established in 1910 in France by the creator and founder of the company Gabrielle Chanel. She has had a tremendous impact on the fashion world, providing revolutionary ideas and liberating women. Her creations were fresh, bold, unusual and very successful. The marketing and brand have been constructed around her life and creative endeavours. This study identified how the brand is able to convey a brand’s message and brand’s values through storytelling and how consumers of the brand perceive the brand’s message and the brand itself. Qualitative research methodology was mainly utilised for this study consisting of 3 semi- structured interviews, in English and Russian. The participants of the interviews are keen followers of fashion and are Chanel brand consumers. The secondary data was represented by a review of the scientific articles, articles about Chanel, Youtube and Instagram images and fashion videos. -

Dossier De Presse 2015

Press kit Festival April 23—27 Exhibitions until May 24 www.villanoailles-hyeres.com Jean-Pierre Blanc General Director of Festival Magalie Guérin Fashion curatorship Maida Grégory-Boina Artistic Director for fashion, set design and scenography for the presentations and the fashion shows The 30th edition of the International Raphaëlle Stopin Photography Art Director Festival of Fashion and Photography at Hyères will take place at the villa Villa Noailles, Hyères Noailles between the 23rd and the communauté d’agglomération th Toulon Provence Méditerranée 27 of April, 2015. The exhibitions Montée Noailles 83400 Hyères th [email protected] will run until the 24 of May. T / 04 98 08 01 98 The festival directed by Press | villa Noailles Philippe Boulet Jean-Pierre Blanc and presided [email protected] over by Didier Grumbach, annually T / 06 82 28 00 47 encourages and supports young Press | Festival artists in the fields of fashion and 2e BUREAU - Sylvie Grumbach photography. Thanks to the support [email protected] T / 01 42 33 93 18 of the festival’s partners, several prizes will be awarded to the Presse | International textile and competing young artists. fashion conferences Registration T / +33 (0)1 42 66 64 44 [email protected] Press | Jimmy Pihet : T / +33 (0)1 42 66 64 44 [email protected] COMPETITION Virginie Viard started work at CHANEL in 1987 where she met Karl Lagerfeld and very quickly became his right-hand woman. After five years the designer took her with him to CHLOE where he was Artistic Director at the time. -

Essenza Di Fendi

il primo quotidiano della moda e del lusso Anno XXXI n. 241 Direttore ed editore Direttore MFvenerdì fashion 6 dicembre 2019 MF fashion Paolo Panerai - Stefano RoncatoI 06.12.19 ONLINE SU MFFASHION.COM LE GALLERY FOTOGRAFICHE DELLE COLLEZIONI S-S 2020 ) COURTESY OF FENDI COURTESY EEssenzassenza ddii FFendiendi VENTURINI FENDI CON LE SCENTED BAGUETTE E NANO ( SILVIA LLaa mmaisonaison ddii LLvmhvmh ttornaorna a MMiamiiami pperer eesaltaresaltare iill ssuouo DDna.na. ««DaDa LLagerfeldagerfeld hhoo iimparatomparato a gguardareuardare aavanti».vanti». SSilviailvia VVenturinienturini FFendiendi llanciaancia llaa ppelleelle SSelleriaelleria pprofumatarofumata cconon FFrenesia,renesia, nnuovauova ffragranzaragranza ccreatareata cconon FFrancisrancis KKurkdjian.urkdjian. IInn sscenacena iill pprogettorogetto cconon KKuengueng CCaputo.aputo. A ggennaioennaio vvareràarerà a MMilanoilano uunn ppop-upop-up uuomoomo e ddonnaonna endi torna a Miami per mostrare la sua vera essenza. Essenza per colpire l’olfatto, con il lancio di una fragranza unica per rende- re profumata la pelle Selleria, creata assieme alla maison Francis FKurkdjian di Lvmh. Essenza per stregare lo mente, con un nuovo progetto di design artistico Roman molds con lo studio Kueng Caputo, esposto a Design Miami, in un allestimento che celebra l’headquarter capitolino di Palazzo delle Civiltà. Ma è un primo step per tornare al mondo delle fragranze? «Vedremo, è un primo passo», ha spiegato a MFF Serge Brunschwig, ad e presidente di Fendi, «La tecnica di in- serire il profumo nel cuoio è di Francis Kurkdjian. È un co-branding continua a pag. II BLACKSTAGE di Giampietro Baudo Métiers d’art Difendere quei piccoli gioielli dell’artigianato che so- atelier al numero 31 di rue Cambon. In realtà, spenti i nifattura, per testimoniare il nostro totale legame con no gli atelier e i fornitori che nel corso degli anni hanno riflettori della passerella, il progetto della fashion house questi artigiani. -

MODA Summer 2019.Indd 1 5/23/19 2:27 PM Beached Shot at Oak Street Beach Featuring Clothes from Cynthia’S Vintage Boutique

1 MODA Summer 2019.indd 1 5/23/19 2:27 PM Beached Shot at Oak Street Beach Featuring Clothes from Cynthia’s Vintage Boutique 2 | MODA Magazine | Summer 2019 MODA Summer 2019.indd 2 5/23/19 2:27 PM Beached Shot at Oak Street Beach Featuring Clothes from Cynthia’s Vintage Boutique 3 MODA Summer 2019.indd 3 5/23/19 2:27 PM 4 | MODA Magazine | Summer 2019 MODA Summer 2019.indd 4 5/23/19 2:27 PM 5 MODA Summer 2019.indd 5 5/23/19 2:27 PM 6 | MODA Magazine | Summer 2019 MODA Summer 2019.indd 6 5/23/19 2:27 PM 7 MODA Summer 2019.indd 7 5/23/19 2:27 PM 8 | MODA Magazine | Summer 2019 MODA Summer 2019.indd 8 5/23/19 2:27 PM 99 MODA Summer 2019.indd 9 5/23/19 2:27 PM 10 | MODA Magazine | Summer 2019 MODA Summer 2019.indd 10 5/23/19 2:27 PM 11 MODA Summer 2019.indd 11 5/23/19 2:27 PM 12 | MODA Magazine | Summer 2019 MODA Summer 2019.indd 12 5/23/19 2:27 PM 13 MODA Summer 2019.indd 13 5/23/19 2:27 PM EDITORS-IN-CHIEFS Cecilia Sheppard & Louis Levin PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR Daniel Chae WRITING EDITOR Sarah Eikenberry VISUAL DESIGN EDITORS Angela Liu & Marie Parra STYLING EDITOR Carla Abreu BEAUTY EDITORS Dani O’Connell & Hannah Burnstein ASSISTANT PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR Natalia Rodriguez ASSISTANT WRITING EDITORS Hugo Barrillon & Stella Slorer ASSISTANT VISUAL DESIGN EDITORS Cheryl Hao & Ella Anderson ASSISTANT STYLING EDITORS Georgianna James, Matteo Laspro, & Wendy Xiao WRITERS & CONTRIBUTORS Alexandre LaBossiere-Barrera, Andrea Li, Brinda Rao, Chiara Theophile, Devan Singh, Eleanor Rubin, Elizabeth Winkler, Isabella Hernandez, Katherine Maschka Hitchcock, Melanie Wang, Rosie Albrecht, Shaillander Mann & Yeeqin New MODELS Austin Fitzgerald, Dasha Shifrina, Eli Timoner, Felipe Urrutia, Gaëlle Pinault, Hannah Burnstein, Kamau Stewart, Philippe Welter, Priya Gandhi & Yiqe Liao 14 | MODA Magazine | Summer 2019 MODA Summer 2019.indd 14 5/23/19 2:27 PM LETTER FROM THE EDITORS Where does fashion take you? This was the question we struggled with as we headed into our first issue as Editors-in-Chief.