Sergei Rachmaninoff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rawson Duo Concert Series, 2013-14

What’s Next? Rawson Duo Concert Series, 2013-14 March 7 & 9 Under Construction ~ we haven’t decided on a program yet, but we’ve set aside Friday and Sunday, March 7 & 9 for the dates. A Russian sequel is under consideration with “maxi-atures,” in contrast to today’s miniatures, by Nicolai Medtner, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Sergei Prokofiev — but one never knows. Stay tuned, details coming soon. Beyond that? . as the fancy strikes (check those emails and website) Reservations: Seating is limited and arranged through advanced paid reservation, $25 (unless otherwise noted). Contact Alan or Sandy Rawson, email [email protected] or call 379- 3449. Notice of event details, dates and times when scheduled will be sent via email or ground mail upon request. Be sure to be on the Rawsons’ mailing list. For more information, visit: www.rawsonduo.com H A N G I N G O U T A T T H E R A W S O N S (take a look around) Harold Nelson has had a lifelong passion for art, particularly photo images and collage. It sustained him through years of working in the federal bureaucracy with his last sixteen in Washington DC. He started using his current collage technique in 2004, two years before retirement from his first career and his move from Virginia to Port Townsend. His art is shown frequently at the Northwind Arts Center and other local venues. www.hnelsonart.com Zee View of the Month ~ photography by Allan Bruce Zee "Cadillactica," (detail of a rusting 1946 Cadillac, Vashon Island, Washington 2001) from “Rustscapes,” a group of abstract, close-up photographs of “maturing” vehicles; rust patterns, peeling and sanded paint, and the reflection of light off of beat up cars and trucks. -

Once Upon a Time There Was a Puss in Boots: Hanna Januszewska’S Polish Translation and Adaptation of Charles Perrault’S Fairy Tales

Przekładaniec. A Journal of Literary Translation 22–23 (2009/2010): 33–55 doi:10.4467/16891864ePC.13.002.0856 Monika Woźniak ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS A PUSS IN BOOTS: Hanna Januszewska’s POLISH TRANSLATION AND ADAPTATION OF CHARLES Perrault’s FAIRY TALES Abstract: This article opens with an overview of the Polish reception of fairy tales, Perrault’s in particular, since 1700. The introductory section investigates the long- established preference for adaptation rather than translation of this genre in Poland and provides the framework for an in-depth comparative analysis of the first Polish translation of Mother Goose Tales by Hanna Januszewska, published in 1961, as well as her adaptation of Perrault’s tales ten years later. The examination focuses on two questions: first, the cultural distance between the original French text and Polish fairy- tales, which causes objective translation difficulties; second, the cultural, stylistic and linguistic shifts introduced by Januszewska in the process of transforming her earlier translation into a free adaptation of Perrault’s work. These questions lead not only to comparing the originality or literary value of Januszewska’s two proposals, but also to examining the reasons for the enormous popularity of the adapted version. The faithful translation, by all means a good text in itself, did not gain wide recognition and, if not exactly a failure, it was nevertheless an unsuccessful attempt to introduce Polish readers to the original spirit of Mother Goose Tales. Keywords: translation, adaptation, fairy tale, Perrault, Januszewska The suggestion that Charles Perrault and his fairy tales are unknown in Poland may at first seem absurd, since it would be rather difficult to im- agine anyone who has not heard of Cinderella, Puss in Boots or Sleeping Beauty. -

Shining the Spotlight on New Talent Independent Opera

Independent Opera Shining the spotlight on new talent INDEPENDENT OPERA AT SADLER’S WELLS 2005–2020 Introduction Message from Wigmore Hall Thursday 15 October 2020, 7.30pm In this period of uncertainty, Independent Opera at Sadler’s It gives me great pleasure to welcome Independent Opera Wells is grateful to be able to present its annual Scholars’ to Wigmore Hall for its fourth showcase event. Now, more Independent Opera Recital at Wigmore Hall. For this final concert in Independent than ever, such opportunities are vital for young singers. Opera’s 15-year history, we are thrilled to bring together We are immensely grateful to Independent Opera for its four talented singers: tenor Glen Cunningham, soprano pioneering work and for its extraordinary commitment Scholars’ Recital Samantha Quillish, bass William Thomas, mezzo-soprano to young artists when they need it most. Tonight’s concert Lauren Young and renowned pianist Christopher Glynn. is a great example of the spirit of Independent Opera and all that it has represented over so many years. I hope Antonín Dvorˇák The four emerging artists you will hear tonight were Glen Cunningham tenor that you all enjoy this concert. Cigánské melodie, Op. 55 selected from Independent Opera’s partner conservatoires: Royal College of Music No. 1 Má písenˇ zas mi láskou zní Royal College of Music, Royal Academy of Music, Guildhall John Gilhooly Director No. 4 Když mne stará matka zpívat School of Music & Drama and Royal Conservatoire of Samantha Quillish soprano Moravian Duets, Op. 38 Scotland. The Independent Opera Voice Scholarships were Royal Academy of Music No. -

CALL for PAPERS MLADA-MSHA International Network CLARE-ARTES Research Center (Bordeaux) Organize an International Symposium Оn

CALL FOR PAPERS MLADA-MSHA International Network CLARE-ARTES Research Center (Bordeaux) Organize an international symposium оn 21-22-23 October, 2015 At Bordeaux Grand Theatre FROM BORDEAUX TO SAINT PETERSBURG, MARIUS PETIPA (1818-1910) AND THE « RUSSIAN » BALLET The great academic ballet, known as « Russian ballet », is the product of a historical process initiated in 18th century in Russia and completed in the second part of 19th century by Victor-Marius-Alphonse Petipa (1818-1910), principal ballet master of the Saint Petersburg Imperial Theatres from 1869 to his death. Born in Marseilles in a family of dancers and actors, Marius Petipa, after short- term contracts in several theatres, including Bordeaux Grand Theatre, pursued a more than 50 years long carreer in Russia, when he became « Marius Ivanovitch ». He layed down the rules of the great academic ballet and left for posterity over 60 creations, among which the most famous are still presented on stages all around the world. Petipa’s name has become a synonym of classical ballet. His work has been denigrated, parodied, or reinterpreted ; however, its meaning remains central in the reflection of contemporary choreographers, as we can see from young South African choreographer Dada Masilo’s recent new version of Swan Lake. Moreover, Petipa’s work still fosters controversies as evidenced by the reconstructions of his ballets by S.G. Vikharev at the Mariinsky theatre or Teatro alla Scala, and by Iu. P. Burlaka at the Bolchoï. Given the world-famous name of Petitpa one might expect his œuvre, as a common set of fundamental values for international choreographic culture, to be widely known. -

Song and Dance by Marina Harss N February, the Russian Director Dmitri Final Version” of the Opera

Books & the Arts. PERA O CORY WEAVER/METROPOLITAN WEAVER/METROPOLITAN CORY A scene from Alexander Borodin’s Prince Igor, with Ildar Abdrazakov as Prince Igor Song and Dance by MARINA HARSS n February, the Russian director Dmitri final version” of the opera. It is a jumble of Vladimir Putin’s incursion into Crimea also Tcherniakov produced a new staging of unfinished ideas and marvelous music. comes to mind. Tcherniakov’s Igor is an Alexander Borodin’s Prince Igor at the For his reconstruction, Tcherniakov re- antihero for our time. Metropolitan Opera. It was last per- arranged the order of scenes, cut several Borodin’s opera is the story of a Slavic formed there in 1917, sung in Italian. passages—including Glazunov’s overture— prince who goes off to fight a battle against IThe opera, which was left unfinished at and inserted music originally sketched by a “barbaric” non-Christian neighbor, a Tur- the time of the composer’s sudden death Borodin but never before integrated into the kic tribe known as the Polovtsians (or, more while attending a military ball in 1887, is opera, with orchestrations by Pavel Smelkov, often, as the Cumans), led by the cheerfully based on a twelfth-century Slavic epic, The including a major new monologue for Igor. truculent Khan Konchak. By the second Song of Igor’s Campaign, best known by the He also imagined a new, ambivalent end- act—in Tcherniakov’s staging, it’s the second English-speaking world in a translation by ing, set to a passage from the opera-ballet half of the first—Igor has suffered a brutal Vladimir Nabokov. -

Scholastic ELT CAT2013 FINAL .Indd

NEW BRANDSERIES English Language Teaching Catalogue Popcorn ELT Readers Scholastic ELT Readers Timesaver Resource Books DVD Readers 2013/14 222100021000 UUKK SScholasticcholastic EELTLT CCAT2013_AT2013_ ccover_.inddover_.indd SSec1:3ec1:3 228/11/20128/11/2012 111:161:16 s a teacher of English, we’re sure you will Aagree that teaching a foreign language can be stimulating, rewarding, and, even on occasion, a lot of fun! By the same token, teaching English also requires dedication, hard work and comes with its own unique set of challenges – a busy curriculum, large class sizes and, most commonly, uninspiring teaching materials. Here at Scholastic, we understand teachers and students. We are here to connect with your classes and to save you time. In our range of graded readers and teachers’ resource books you will fi nd a wealth of lively, meaningful content that has the potential to turn an otherwise dull lesson into an exciting one. Your students might fi nd themselves reading a biography of Steve Jobs, practising a Kung Fu Panda Holiday chant or acting out a scene from Shrek! Learning English requires commitment. It takes time and perseverance. It can be challenging and, at times, frustrating. But, most importantly, it should also be fun. At Scholastic, we’ve never lost sight of that. Wishing you and your students all the best for the future! Jacquie Bloese Publisher www.scholasticeltreaders.com SScholasticcholastic EELTLT CCAT2013_FINAL_.inddAT2013_FINAL_.indd 2 228/11/20128/11/2012 110:580:58 Contents Popcorn Readers pages 4–15 Introduction -

Boston Ballet: Next Generation, 2016

HOME (HTTP://CRITICALDANCE.ORG/) / BALLET (USA & CANADA) (HTTP://CRITICALDANCE.ORG/CATEGORY/BALLET-USA-CANADA/) Boston Ballet: Next Generation, 2016 ! June 4, 2016 Boston Opera House Boston, MA May 18, 2016 Carla DeFord In its annual “Next Generation” program, Boston Ballet (BB) features students, trainees, and pre-professional dancers with music accompaniment performed by the New England Conservatory (NEC) Youth Orchestra. Having attended this event since 2014, I have to say that the star of this year’s show was Geneviève Leclair, assistant conductor of the Boston Ballet Orchestra, who guest conducted the NEC ensemble. There were also several memorable dancers, but the award for sustained achievement in music performance, including Act III of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty and excerpts from Ambroise Thomas’s Hamlet, goes to Leclair, who conducted the orchestra with such verve and precision that its members sounded not like the students they are, but like seasoned professionals. In addition to being essential to the audience’s enjoyment of the program, the music was an absolute gift to the dancers because it gave them the structure and direction they needed. Leclair’s confident dynamics and tempos, crisp rhythms, and crystalline phrasing created powerful forward momentum. Moreover, each style in the Tchaikovsky score was vividly realized – from the meowing of Puss in Boots and the White Cat, to the chirping of the Bluebird, to the stirring rhythms of the polonaise and mazurka. How wonderful for the dancers to be supported by music of such high caliber. Act III of The Sleeping Beauty (with choreography by Marius Petipa, Peter Martins after Petipa, and Alla Nikitina, a Boston Ballet School faculty member) also introduced us to the second star of the evening: Lex Ishimoto as the Bluebird. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Contact:Dianela Acosta

Contact: Dianela Acosta | Phone: 646-438-0110 | Email: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE PURRFECT INTRODUCTION TO OPERA, BOULDER OPERA’S FAMILY SHOW: PUSS IN BOOTS Boulder Opera performs Puss in Boots (English and Spanish versions) in Boulder and Lafayette for ages 3 and up Boulder/Lafayette, CO - This February 2020, Boulder Opera announces the revival and Colorado Premiere of the fairy tale Puss in Boots/Il Gato con Botas. Xavier Montsalvatge’s take on the classic story of an ingenious and quick-witted feline with magical talents is sure to entertain the whole family. Can Puss win the princess’ hand for his master? Will he outwit the evil ogre? Don’t miss the talented Boulder Opera singers and orchestra that will turn this fairytale into an afternoon of magical and adventurous opera. Just one hour and followed by a Q&A with the cast. For ages 3 and up. Returning this season as artistic director is Michael Travis Risner, a Boulder-based singer and director. “It is with great pleasure that we at Boulder Opera present Puss in Boots, or, in the original Spanish, Il Gato con Botas. Premiered in Spain in 1946, we are so happy to stage this wonderful work - a classic telling of the original Puss in Boots legend. Our audience will encounter not only the titular cat, but also the scary ogre whom he deceives, the beautiful princess, and the humble miller. For those familiar only with Puss from the popular Dreamworks movies, this will be a fun and unique way to learn the original story--an origin story, if you will--of one of their favorite characters.” Executive producer, Nadia Artman adds, “The Puss in boots production will be spectacularly beautiful and fit for all ages. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

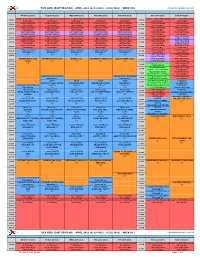

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Guild Gmbh Guild -Historical Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen/TG, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - E-Mail: [email protected] CD-No

Guild GmbH Guild -Historical Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen/TG, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Composer/Track Artists GHCD 2201 Parsifal Act 2 Richard Wagner The Metropolitan Opera 1938 - Flagstad, Melchior, Gabor, Leinsdorf GHCD 2202 Toscanini - Concert 14.10.1939 FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) Symphony No.8 in B minor, "Unfinished", D.759 NBC Symphony, Arturo Toscanini RICHARD STRAUSS (1864-1949) Don Juan - Tone Poem after Lenau, op. 20 FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809) Symphony Concertante in B flat Major, op. 84 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor (Orchestrated by O. Respighi) GHCD Le Nozze di Figaro Mozart The Metropolitan Opera - Breisach with Pinza, Sayão, Baccaloni, Steber, Novotna 2203/4/5 GHCD 2206 Boris Godounov, Selections Moussorgsky Royal Opera, Covent Garden 1928 - Chaliapin, Bada, Borgioli GHCD Siegfried Richard Wagner The Metropolitan Opera 1937 - Melchior, Schorr, Thorborg, Flagstad, Habich, 2207/8/9 Laufkoetter, Bodanzky GHCD 2210 Mahler: Symphony No.2 Gustav Mahler - Symphony No.2 in C Minor „The Resurrection“ Concertgebouw Orchestra, Otto Klemperer - Conductor, Kathleen Ferrier, Jo Vincent, Amsterdam Toonkunstchoir - 1951 GHCD Toscanini - Concert 1938 & RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis NBC Symphony, Arturo Toscanini 2211/12 1942 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Symphony No. 3 in F Major, op. 90 GUISEPPE MARTUCCI (1856-1909) Notturno, Novelletta; PETER IILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840- 1893) Romeo and Juliet