Eldritch Horrors: the Modernist Liminality of H.P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spawn Monsters

TM TM WELCOME TO INNSMOUTH COMPONENTS A rotting fishing village on the coast of Massachusetts, Your copy of Innsmouth Horror should include the Innsmouth is being devoured from within by a cancer. following components: The Marsh family, greatly respected in the town by most, • This Rulebook have long brought prosperity to the little village, but only • 1 Expansion Game Board they know at what cost. For just off the shore, beneath the • 16 Investigator Sheets waves, lies a secret so terrible that the Marshes would • 16 Investigator Markers destroy anyone and anything to protect it. The investigators • 16 Plastic Investigator Stands must venture into this xenophobic backwater, fearing for • 96 Investigator Cards their very lives, in order to stop the plans of the Ancient » 96 Personal Stories One. The investigators will find no allies in Innsmouth, • 8 Ancient One Sheets and few safe havens. But if they are to stop the advance of • 176 Ancient One Cards the terrible Deep Ones, they have no other choice. » 36 Arkham Location Cards The Innsmouth Horror expansion to Arkham Horror » 42 Innsmouth Location Cards adds the neighboring town of Innsmouth. It includes new » 36 Mythos Cards investigators, new Ancient Ones, new monsters, and new » 16 Gate Cards cards that may be used with the base Arkham Horror » 24 Ancient One Plot Cards game. It also features new game elements including a » 10 Innsmouth Look Cards new board, new heralds, personal story cards for each » 12 Small Dust Cards investigator, and the Deep Ones Rising track. • 2 Herald Sheets • 32 Monster Markers • 6 Uprising Tokens Using This Book • 8 Ghatanothoa’s Visage Tokens • 1 Zhar Token The first part of this rulebook contains rules for playing • 2 Aquatic Markers Arkham Horror with the Innsmouth Horror expansion. -

Lovecraft's Terrestrial Terrors: Morally Alien Earthlings

7 ARTIGO http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/abusoes.2017.27816 01 LOVECRAFT’S TERRESTRIAL TERRORS: MORALLY ALIEN EARTHLINGS Greg Conley (EKU) Recebido em 05 mar 2017. Greg Conley is Adjunct Instructor of Humanities, Aprovado em 30 mar 2017 Ph.D. in Literary and Cultural Studies, MFA in Creative Writing, of the Department of Languages, Cultures, and Humanities. Expert Areas: Victorian Literature; Science Fiction/Fantasy/Horror. Email: gregory. [email protected]. Abstract: Lovecraft’s cosmic horror led him to create aliens that did not exist on the same moral spectrum as humanity. That is one of many ways Lovecraft’s work insists humans do not matter in the cosmos. However, most of the work on Lovecraft has focused on the space aliens, and how they are necessarily alien to humans, because they are from other worlds. Lovecraft’s terrestrial aliens, such as the Deep Ones, the Old Ones, and the Shoggoths, are less alien, but just as morally strange. Lovecraft used biological horror to create his terrestrial aliens, and in turn used them to claim that morality was a product of human evolution and history. A life form with a separate evolutionarily history would necessarily have a separate and incomprehensible morality. Lovecraft illustrates that point with narrators who are ultimately sympathetic with the aliens, despite the threat they pose to the narrators and to everything they have ever known. Keywords: Fiction; Cosmic horror; Biologic horror. REVISTA ABUSÕES | n. 04 v. 04 ano 03 8 ARTIGO http://dx.doi.org/10.12957/abusoes.2017.27816 Resumo: O horror cósmico de Lovecraft o conduziu a criar alienígenas que não existem no mesmo escopo moral da humanidade. -

Shining the Spotlight on New Talent Independent Opera

Independent Opera Shining the spotlight on new talent INDEPENDENT OPERA AT SADLER’S WELLS 2005–2020 Introduction Message from Wigmore Hall Thursday 15 October 2020, 7.30pm In this period of uncertainty, Independent Opera at Sadler’s It gives me great pleasure to welcome Independent Opera Wells is grateful to be able to present its annual Scholars’ to Wigmore Hall for its fourth showcase event. Now, more Independent Opera Recital at Wigmore Hall. For this final concert in Independent than ever, such opportunities are vital for young singers. Opera’s 15-year history, we are thrilled to bring together We are immensely grateful to Independent Opera for its four talented singers: tenor Glen Cunningham, soprano pioneering work and for its extraordinary commitment Scholars’ Recital Samantha Quillish, bass William Thomas, mezzo-soprano to young artists when they need it most. Tonight’s concert Lauren Young and renowned pianist Christopher Glynn. is a great example of the spirit of Independent Opera and all that it has represented over so many years. I hope Antonín Dvorˇák The four emerging artists you will hear tonight were Glen Cunningham tenor that you all enjoy this concert. Cigánské melodie, Op. 55 selected from Independent Opera’s partner conservatoires: Royal College of Music No. 1 Má písenˇ zas mi láskou zní Royal College of Music, Royal Academy of Music, Guildhall John Gilhooly Director No. 4 Když mne stará matka zpívat School of Music & Drama and Royal Conservatoire of Samantha Quillish soprano Moravian Duets, Op. 38 Scotland. The Independent Opera Voice Scholarships were Royal Academy of Music No. -

Charisma, Medieval and Modern

Charisma, Medieval and Modern Edited by Peter Iver Kaufman and Gary Dickson Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Peter Iver Kaufman and Gary Dickson (Eds.) Charisma, Medieval and Modern This book is a reprint of the special issue that appeared in the online open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) in 2012 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special_issues/charisma_medieval). Guest Editors Peter Iver Kaufman Jepson School, University of Richmond Richmond, VA, USA Gary Dickson School of History, Classics, and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, EH, Scotland, UK Editorial Office MDPI AG Klybeckstrasse 64 Basel, Switzerland Publisher Shu-Kun Lin Production Editor Jeremiah R. Zhang 1. Edition 2014 0'3,%DVHO%HLMLQJ ISBN 978-3-03842-007-1 © 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. All articles in this volume are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. However, the dissemination and distribution of copies of this book as a whole is restricted to MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. III Table of Contents List of Contributors ............................................................................................................... V Preface -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Malleus Monstrorumsampleexpanded English File Edition Is Published by Chaosium Inc

Sample file —EXPANDED ENGLISH EDITION IN 380 ENTRIES— by Scott David Aniolowski with Sandy Petersen & Lynn Willis Additional Material by: David Conyers, Keith Herber, Kevin Ross, ChadSample J. Bowser, Shannon file Appel, Christian von Aster, Joachim A. Hagen, Florian Hardt, Frank Heller, Peter Schott, Steffen Schuütte, Michael Siefner, Jan Cristof Steines, Holger Göttmann, Wolfang Schiemichen, Ingo Ahrens, and friends. For fuller Author credits see pages 4 and 288. Project & Layout: Charlie Krank Cover Painting: Lee Gibbons Illustrated by: Pascal D. Bohr, Konstantyn Debus, Nils Eckhardt, Thomas Ertmer, Kostja Kleye, Jan Kluczewitz, Christian Küttler, Klaas Neumann, Patrick Strietzel, Jens Weber, Maria Luisa Witte, Lydia Ortiz, Paul Carrick. Art direction and visual concept: Konstantyn Debus (www.yllustration.com) Participants in the German Edition: Frank Heller, Konstantyn Debus, Peter Schott, Thomas M. Webhofer, Ingo Ahrens, Jens Kaufmann, Holger Göttmann, Christina Wessel, Maik Krüger, Holger Rinke, Andreas Finkernagel, 15brötchenmann Find more information at www.pegasus.de German to English Translation: Bill Walsh Layout Assistance: Alan Peña, Lydia Ortiz Chaosium is: Lynn Willis, Charlie Krank, Dustin Wright, Fergie, and a few odd critters. A CHAOSIUM PUBLICATION • 2006 M’bwa, megalodon, the Million Favoured Ones, the Complete Credits mind parasites, the miri nigri, M’nagalah, Mordiggian, moose, M’Tlblys, the nioth-korghai, Nug & Yeb, octo- Scott David Aniolowski: the children of Abhoth, pus, Ossadagowah, Othuum, the minions of Othuum, -

Kuhn-Conference Paper

Lina Kuhn [email protected] Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill “Affect and Deep Time in Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth, and the Turn Towards Thinking Through the Epoch of the Anthropocene” Mark McGurl begins his article “The Posthuman Comedy” with an analysis of a work by Wai Chee Dimock entitled Through Other Continents: American Literature across Deep Time as a way to think through the concept of deep time and its appearance in fiction. McGurl states that “the perspective of deep time holds the promise, for Dimock, of reinvigorating ‘our very sense of the connectedness among human beings’” which becomes important in, for instance, “dissuading us from the wisdom of war” (McGurl 533). I will return later to the possible benefits of thinking of the ‘connectedness among human beings,’ or as Dipesh Chakrabarty states in his article “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” “the knowledge of humans as a species,” but first I would like to explore the ways in which a work of fiction might gesture towards those benefits on its own terms (Chakrabarty 219). In 1936 H.P. Lovecraft published his novella The Shadow Over Innsmouth, a horror story told by a nameless narrator about his encounters with an alien species in an American town shunned by the rest of the country. The narrator of this tale, through the abjection and horror caused by his loss of agency in relation to the aliens and their status as other, reveals how a sense of deep time changes a human’s reactions to his situation. -

The Unspeakable Oath Issues 1 & 2 Page 1

The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 1 Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath ©1993 John Tynes This is a series of freely-distributable text files that presents the textual contents of early issues of THE UNSPEAKABLE OATH, the world’s premiere digest for Chaosium’s CALL OF CTHULHU ™ role-playing game. Each file contains the nearly-complete text from a given issue. Anything missing is described briefly with the file, and is missing either due to copyright problems or because the information has been or will be reprinted in a commercial product. Everything in this file is copyrighted by the original authors, and each section carries that copyright. This file may be freely distributed provided that no money is charged whatsoever for its distribution. This file may only be distributed if it is intact, whole, and unchanged. All copyright notices must be retained. Modified versions may not be distributed — the contents belong to the creators, so please respect their work. Abusing my position as editor and instigator of the magazine and this project, I have taken the liberty of adding comments to some of the contents where I thought I had something interesting or historically worth preserving to say. Yeah, right! – John Tynes, editor-in-chief of Pagan Publishing The Unspeakable Oath issues 1 & 2 Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction to The Annotated Unspeakable Oath...................................................................................2 Introduction to TUO 1.........................................................................................................................4 -

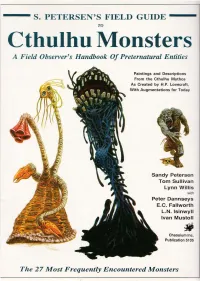

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Impact of a Two-Week

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Impact of a Two-week Daily Intervention on Increased and Sustained Experiences of Awe THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Sean Patrick Goldy Master’s Committee: Assistant Professor Paul K. Piff, Chair Professor Roxane Cohen Silver Professor Peter Ditto 2020 © 2020 Sean Patrick Goldy TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iii LIST OF TABLES iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Literature Review 1 Awe and Longitudinal Work 4 CHAPTER 2: The Present Study 7 CHAPTER 3: Method 7 Sample and Procedures 7 Measures 9 Analytic Strategy 11 CHAPTER 5: Results 12 Exploratory Analyses 14 CHAPTER 6: Discussion 16 Limitations and Future Directions 18 REFERENCES 21 APPENDIX A: Figures and Tables 26 ii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1 26 Figure 2 26 Figure 3 27 Figure 4 27 Figure 5 28 Figure 6 28 Figure 7 29 Figure 8 29 Figure 9 29 Figure 10 30 iii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1 Mean scores for daily reported emotions over the intervention period 31 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to all who have been with me along each step of this process. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Impact of a Two-week Daily Intervention on Increased and Sustained Experiences of Awe by Sean Patrick Goldy Master of Arts in Social Ecology University of California, Irvine, 2020 Associate Professor Paul K. Piff, Chair The emotion awe is associated with numerous individual and social benefits, including increased physical and mental health, prosocial behavior, and humility (Stellar et al., 2017). -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven.