Raptor-Rescue-Handbook.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vedlegg Til Forskriftsforslaget

Vedlegg til forskriftsforslaget Forklaringer til artslisten, annotasjoner og fotnoter Vedlegg 1: Artslister (A, B, C) Vedlegg 2: Innførselsrestriksjoner Vedlegg 3: Merke- og sertifiseringskrav Postadresse: postboks 5672, Sluppen, 7485 Trondheim | Tel: 03400/73 58 05 00 | Faks: 73 58 05 01 | Org.nr: 999 601 391 Besøksadresse Oslo: Grensesvingen 7, 0661 Oslo | Besøksadresse Trondheim: Brattørkaia 15, 7010 Trondheim Saksbehandler: | E-post: [email protected] | Internett: www.miljødirektoratet.no VEDLEGG I Forklaringer til liste A, B, og C Generelt om artene Vedlegg I, liste A, skal omfatte arter som er utrydningstruet og oppført i konvensjonens liste I. I tillegg omfattes arter som ikke er oppført i konvensjonens liste I, men som er så sjeldne at enhver form for handel vil sette den gjeldende arts overlevelsesevne i fare. Videre omfattes også arter som lett kan forveksles med arter som er oppført i listen. Tilsvarende gjelder arter hvor de fleste underarter er oppført i listen. Vedlegg I, liste B, omfatter arter som ikke nødvendigvis er truet av utryddelse nå, men som kan bli det dersom handelen med artene ikke reguleres. Listen omfatter de i konvensjonens liste II, bortsett fra de arter som står oppført i vedlegg I, liste A og for hvilke Norge eventuelt ikke har tatt forbehold mot, samt de i liste B oppførte arter som Norge eventuelt har tatt forbehold mot. Listen omfatter videre enhver annen art, som ikke står oppført i konvensjonens lister, men som er gjenstand for internasjonal handel av et visst omfang eller som truer overlevelsen av arten eller populasjoner av arten i visse land, eller at den samlede populasjonen kan opprettholdes på et nivå som er i overenstemmelse med den gjeldende arts rolle i de økosystemer hvor den forekommer. -

Summary of Issues to Be Discussed at the Sixteenth

SUMMARY OF ISSUES TO BE DISCUSSED AT THE TWENTY-EIGHTH MEETING OF THE CITES ANIMALS COMMITTEE TEL AVIV, ISRAEL • 30 AUGUST-3 SEPTEMBER 2015 AC = Animals Committee ● PC = Plants Committee ● SC = Standing Committee ● RC = Resolution Conf. ● Dec. = Decision ● CoP = Conference of the Parties All meeting documents prepared by the CITES Secretariat unless otherwise indicated. All trade data from the CITES Trade Database. ISSUE PROPOSED ACTIONS SSN RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Opening of the Meeting No document. No comment. No Document 2. Rules of Procedure Contains Rules of Procedure (RoP) adopted at AC27 Regarding Rule 13, SSN recommends that AC adopt the first option: to (April-May 2014) with two recommended changes. elect the Chair and Vice-Chair following the CoP via postal procedure. AC28 Doc. 2 Proposes Rule 13 be changed to either: While SSN agrees that it is helpful to elect Chair and Vice-Chair as soon That regional representatives or their alternates as possible after the CoP, all representatives should be provided the present at the CoP elect a Chair and Vice-Chair opportunity to stand for these positions and participate in any vote. immediately following the CoP and in case no Regarding Rule 20, SSN urges the AC to reject the proposed changes. quorum is attained, by the postal procedure Documents should be required to be submitted by a firm deadline so that contained in Rules 32 to 34, in which case the duties Parties and Committee Members are provided sufficient time to review and of the Chair shall be discharged by the previous consider all documents fully in advance of the meetings. -

Trainee Bander's Diary (PDF

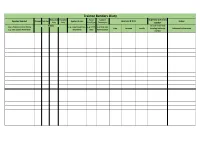

Trainee Banders Diary Extracted Handled Band Capture Supervising A-Class Species banded Banded Retraps Species Groups Location & Date Notes Only Only Size/Type Techniques Bander Totals Include name and Use CAVS & Common Name e.g. Large Passerines, e.g. 01AY, e.g. Mist-net, Date Location Locode Banding Authority Additional information e.g. 529: Superb Fairy-wren Shorebirds 09SS Hand Capture number Reference Lists 05 SS 10 AM 06 SS 11 AM Species Groups 07 SS 1 (BAT) Small Passerines 08 SS 2 (BAT) Large Passerines 09 SS 3 (BAT) Seabirds 10 SS Shorebirds 11 SS Species Parrots and Cockatoos 12 SS 6: Orange-footed Scrubfowl Gulls and Terns 13 SS 7: Malleefowl Pigeons and Doves 14 SS 8: Australian Brush-turkey Raptors 15 SS 9: Stubble Quail Waterbirds 16 SS 10: Brown Quail Fruit bats 17 SS 11: Tasmanian Quail Ordinary bats 20 SS 12: King Quail Other 21 SS 13: Red-backed Button-quail 22 SS 14: Painted Button-quail Trapping Methods 23 SS 15: Chestnut-backed Button-quail Mist-net 24 SS 16: Buff-breasted Button-quail By Hand 25 SS 17: Black-breasted Button-quail Hand-held Net 27 SS 18: Little Button-quail Cannon-net 28 SS 19: Red-chested Button-quail Cage Trap 31 SS 20: Plains-wanderer Funnel Trap 32 SS 21: Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove Clap Trap 33 SS 23: Superb Fruit-Dove Bal-chatri 34 SS 24: Banded Fruit-Dove Noose Carpet 35 SS 25: Wompoo Fruit-Dove Phutt-net 36 SS 26: Pied Imperial-Pigeon Rehabiliated 37 SS 27: Topknot Pigeon Harp trap 38 SS 28: White-headed Pigeon 39 SS 29: Brown Cuckoo-Dove Band Size 03 IN 30: Peaceful Dove 01 AY 04 IN 31: Diamond -

Revised 22/05/2009

2009R0407 — EN — 22.05.2009 — 000.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 407/2009 of 14 May 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein (OJ L 123, 19.5.2009, p. 3) Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 139, 5.6.2009, p. 35 (407/2009) 2009R0407 — EN — 22.05.2009 — 000.001 — 2 ▼B COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 407/2009 of 14 May 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein (1), and in particular Article 19(3) thereof, Whereas: (1) Regulation (EC) No 338/97 lists animal and plant species in respect of which trade is restricted or controlled. Those lists incorporate the lists set out in the Appendices to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, hereinafter ‘the CITES Convention’. (2) The following species have been added to Appendix III to the CITES Convention at the request of China: Corallium elatius, Corallium japonicum, Corallium konjoi and Corallium secundum. (3) The species Crax daubentoni, Crax globulosa, Crax rubra, Ortalis vetula, Pauxi pauxi, Penelopina -

Ec) No 1332/2005

19.8.2005 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 215/1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) NO 1332/2005 of 9 August 2005 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, of Namibia and South Africa), Euphorbia spp., Orchidaceae, Cistanche deserticola and Taxus wallichiana were amended. Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, (5) The species Malayemis subtrijuga, Notochelys platynota, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of Amyda cartilaginea, Carettochelys insculpta, Chelodina 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna mccordi, Uroplatus spp., Carcharodon carcharias (currently and flora by regulating trade therein (1), and in particular listed on Appendix III), Cheilinus undulatus, Lithophaga Article 19(3), thereof, lithophaga, Hoodia spp., Taxus chinensis, T. cuspidata, T. fuana, T. sumatrana), Aquilaria spp. (except for A. malaccensis, which was already listed in Appendix II), Whereas: Gyrinops spp. and Gonystylus spp. (previously listed in Appendix III) were included in Appendix II to the Convention. (1) At the 13th session of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, hereinafter ‘the Convention’, held in Bangkok (Thailand) in October (6) The species Agapornis roseicollis was deleted from 2004, certain amendments were made to the Appendices Appendix II to the Convention. to the Convention. (2) The species Orcaella brevirostris, Cacatua sulphurea, Ama- zona finschi, Pyxis arachnoides and Chrysalidocarpus decipiens (7) Subsequent to the thirteenth session of the Conference of were transfered from Appendix II to the Convention to the Parties to the Convention, the Chinese populations of Appendix I thereto. -

COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the Protection of Species of Wild Fauna and Flora by Regulating Trade Therein (OJ L 61, 3.3.1997, P

1997R0338 — EN — 27.11.1997 — 002.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents "B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein (OJ L 61, 3.3.1997, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date "M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 938/97 of 26 May 1997 L 140 1 30.5.1997 "M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 2307/97 of 18 November 1997 L 325 1 27.11.1997 Corrected by: "C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 298, 1.11.1997, p. 70 (338/97) 1997R0338 — EN — 27.11.1997 — 002.001 — 2 !B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Article 130s (1) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the Commission (1), Having regard to the opinion of the Economic and Social Committee (2), Acting in accordance with the procedure laid down in Article 189c of the Treaty (3), (1) Whereas Regulation (EEC) No 3626/82 (4) applies the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in the Community with effect from 1 January 1984; whereas the purpose of the Convention is to protect endangered species of fauna and flora through controls on international trade in specimens of those species; (2) Whereas, in order to improve the protection of species of wild fauna and flora which are -

Australian Museum Annualreport 2008.Pdf

The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Sir, In accordance with the provisions of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983 we have pleasure in submitting this report of the activities of the Australian Museum Trust for the financial year ended 30 June 2008, for presentation to Parliament. On behalf of the Australian Museum Trust, Brian Sherman AM President of the Trust Frank Howarth Secretary of the Trust Australian Museum Annual Report 2007–2008 02 03 MINISTER TRUSTEES The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP Brian Sherman AM (President) Premier and Minister for the Arts Brian Schwartz AM (Deputy President) till 31 December 2007 GOVERNANCE Michael Alscher from 1 January 2008 Cate Blanchett The Museum is governed by a Trust David Handley established under the Australian Museum Dr Ronnie Harding Trust Act 1975. The Trust currently has Sam Mostyn nine members, one of whom must have Dr Cindy Pan knowledge of, or experience in, science and Michael Seyffer one of whom must have knowledge of, or Julie Walton OAM experience in, education. The amended Act increases the number of Trustees from nine DIRECTOR to eleven and requires that one Trustee has knowledge of, or experience in, Australian Frank Howarth Indigenous culture. Trustees are appointed Appendix A presents profiles of the Trustees. by the Governor on the recommendation of Appendix B sets out the Trust’s activities and the Minister for a term of up to three years. committees during the year. Appendix D sets Trustees may hold no more than three terms. -

(1) Whereas Regulation (EEC) No 3626/82

3 . 3 . 97 1 EN Official Journal of the European Communities No L 61/ 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COUNCIL REGULATION ( EC ) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION , a Regulation taking account of the scientific knowledge acquired since its adoption and the current structure of trade ; whereas , moreover , the abolition of controls at internal borders resulting Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European from the Single Market necessitates the adoption Community, and in particular Article 130s ( 1 ) thereof, of stricter trade control measures at the Community's external borders, with documents and goods being checked at the customs office at the border where they are introduced ; Having regard to the proposal from the Commission ('), Having regard to the opinion of the Economic and Social Committee ( 2 ), ( 3 ) Whereas the provisions of this Regulation do not prejudice any stricter measures which may be taken or maintained by Member States, in compliance with the Treaty, in particular with regard to the Acting in accordance with the procedure laid down in holding of specimens of species covered by this Article 189c of the Treaty ( 3 ), Regulation ; ( 1 ) Whereas Regulation ( EEC ) No 3626/82 ( 4 ) applies the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in the ( 4 ) Whereas it is necessary to lay down objective Community with effect from 1 January 1984 ; criteria for the inclusion -

State of the Parks Report Director of National Parks Annual Report 2008–09 Supplementary Information

State of the parks report Director of National Parks Annual Report 2008–09 Supplementary Information Managing the Australian Government’s protected areas State of the parks report Guide to the state of the parks report The State of the Parks report presents systematic and consistent background information on each Commonwealth reserve proclaimed under the EPBC Act and for Calperum and Taylorville Stations. The following information is common to the reports on each place: t Area and locational information is derived from the Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database and from a departmental Marine Protected Areas dataset–which includes data sourced from Geoscience Australia t The World Conservation Union (IUCN) protected area management category is identified for each reserve, and where some of the reserve are assigned to different categories this is indicated. The IUCN categories are formally assigned under the EPBC Act, and schedule 8 of the EPBC Regulations defines the Australian IUCN reserve management principles applying to each category. t Where possible, each reserve’s biogeographic context is described by reference to the national biogeographic regionalisations: terrestrial (Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia) or marine (Interim Marine and Coastal Regionalisation for Australia). t The report summarises the relevance of international agreements to each reserve, recognising both the international significance of the reserves and the Director’s legal responsibility to take account of Australia’s obligations under each agreement. t The report summarises the occurrence in each reserve of species listed under the EPBC Act as threatened, migratory or marine, and the status of relevant recovery plans. t Information on the total number of different types of plant and animal species recorded for each place is included, to the extent of available knowledge. -

Threatened Species Strategy Year 3 Scorecard – Norfolk Island Boobook Owl

Threatened Species Strategy – Year 3 Priority Species Scorecard (2018) Norfolk Island Boobook Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata Key Findings Norfolk Island Boobook Owls nearly became extinct in the 1980s, following extensive historic clearing of habitat and nesting trees. Very few natural nesting sites remain on the island and the small population of owls is now highly inbred. Conservation efforts have focused on securing nest sites and culling nest competitors, such as introduced rosellas, however there has been no successful breeding observed since 2012. Photo: Amy Svendsen Significant trajectory change from 2005-15 to 2015-18? No, population currently stable, although outlook is poor. Priority future actions • Research to determine whether genetic constraints or poor nestbox placement are the primary reasons for the apparent lack of breeding • Intensive crimson rosella and rat control to reduce the risk of predation and competition • Provide and maintain rat proof nest boxes for roosting and breeding both within the national park and community wide where breeding birds are known to occur Full assessment information Background information 2018 population trajectory assessment 1. Conservation status and taxonomy 8. Expert elicitation for population trends 2. Conservation history and prospects 9. Immediate priorities from 2019 3. Past and current trends 10. Contributors 4. Key threats 11. Legislative documents 5. Past and current management 12. References 6. Support from the Australian Government 13. Citation 7. Measuring progress towards conservation The primary purpose of this scorecard is to assess progress against achieving the year three targets outlined in the Australian Government’s Threatened Species Strategy, including estimating the change in population trajectory of 20 bird species. -

Canberra Bird Notes Canberra

canberra bird notes Volume 3 Number 6 April 1976 EDITORIAL The preceding numbers of Canberra Bird Notes have generally varied between 12 and 24 pages, with vol. l no. 6 reaching 28 pages. Thanks are due to the large number of contributors who continue to provide copy and who have made this, the first 32 -page CBN issue, possible. Keep up the good work. NAMES TO BE USED IN CANBERRA BIRD NOTES Generally, CBN will now follow the names used in Checklist of the Birds of Australia, Part 1, Non - Passerines by H.T. Condon (RAOU, 1975) and Interim List of Australian Song Birds, Passerines by R. Schodde (RAOU, 1975). Exceptions will be the series entitled 'Status of Birds of Canberra and District', which will follow the names used in Birds in the Australian High Countr y edited by H.J. Frith (1969) and A Field-list of the Birds of Canberra and District. WHO TOOK THE BIRDS OUT OF BRITISH ORNITHOLOGY? C.J. Bibby We all watch birds in our own individual ways irrespective of the level of interest. Too infrequently it appears that we stop to think what it's all about. Our thanks are due to David Purchase who brought the following thoughtful article to notice and secured permission to republish it here. Our special thanks to the editors of British Birds and to the publishers, Macmillan Journals Ltd, for permitting republication. Colin Bibby is an amateur birdwatcher by inclination and an ornithologist by profession. He currently lives in Dorset where he is studying the Dartford Warbler for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. -

COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the Protection of Species of Wild Fauna and Flora by Regulating Trade Therein (OJ L 61, 3.3.1997, P

1997R0338 — EN — 19.10.1998 — 003.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents "B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein (OJ L 61, 3.3.1997, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date "M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 938/97 of 26 May 1997 L 140 1 30.5.1997 "M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 2307/97 of 18 November 1997 L 325 1 27.11.1997 "M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 2214/98 of 15 October 1998 L 279 3 16.10.1998 Corrected by: "C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 298, 1.11.1997, p. 70 (338/97) 1997R0338 — EN — 19.10.1998 — 003.001 — 2 !B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Article 130s (1) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the Commission (1), Having regard to the opinion of the Economic and Social Committee (2), Acting in accordance with the procedure laid down in Article 189c of the Treaty (3), (1) Whereas Regulation (EEC) No 3626/82 (4) applies the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in the Community with effect from 1 January 1984; whereas the purpose of the Convention is to protect endangered species of fauna and flora through controls on international trade in specimens of those species; (2) Whereas,