West Africa Fruit -Scoping Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Étude Originale

Étude originale Distribution des espèces de Striga et infestation des cultures céréalières dans le nord de la Côte d'Ivoire Charles Konan Kouakou1,2 2 Résumé Louise Akanvou Les cultures ce´re´alie`res sont pour la plupart infeste´es par des espe`ces de Striga dans le nord 1 Irie Arsène Zoro Bi de la Coˆte d’Ivoire. Dans cette e´tude, les espe`ces de Striga, leur re´partition, abondance et 2 Rene Akanvou intensite´ d’infestation ont e´te´ de´termine´es. Les surfaces de ce´re´ales infeste´es ont e´te´ 1,2 Hugues Annicet N'da estime´es. Les donne´es ont e´te´ collecte´es a` travers des enqueˆtes extensives et intensives. 1 Universite Nangui Abrogoua Des e´chantillonnages ont e´te´ re´alise´s dans des champs cultive´s. Selon la carte des zones Unite de formation et de recherche d’infestation de Striga actualise´e, les zones infeste´es couvrent le nord du pays de 8˚47,17’ a` des sciences de la nature 10˚38,84’ de latitude nord et de 2˚47,68’ a` 7˚55,20’ de longitude ouest. La zone infeste´e 02 BP 801 occupe une superficie cultivable de 3 191 850 ha. Un total de 71,8 % des villages situe´s Abidjan 02 dans cette zone sont infeste´s par Striga spp. L’hypothe`se d’e´volution des infestations Côte d'Ivoire suivant un gradient nord-sud a e´te´ confirme´e. Les infestations ont commence´ en zone de <[email protected]> <[email protected]> savane soudanienne et ont atteint la moitie´ de la zone de savane sub-soudanienne. -

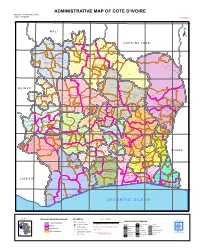

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Côte D'ivoire

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT HOSPITAL INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION AND BASIC HEALTHCARE SUPPORT REPUBLIC OF COTE D’IVOIRE COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION MARCH-APRIL 2000 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS, WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES, SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS BASIC DATA AND PROJECT MATRIX i to xii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 PROJECT OBJECTIVES AND DESIGN 1 2.1 Project Objectives 1 2.2 Project Description 2 2.3 Project Design 3 3. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 3 3.1 Entry into Force and Start-up 3 3.2 Modifications 3 3.3 Implementation Schedule 5 3.4 Quarterly Reports and Accounts Audit 5 3.5 Procurement of Goods and Services 5 3.6 Costs, Sources of Finance and Disbursements 6 4 PROJECT PERFORMANCE AND RESULTS 7 4.1 Operational Performance 7 4.2 Institutional Performance 9 4.3 Performance of Consultants, Contractors and Suppliers 10 5 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT 11 5.1 Social Impact 11 5.2 Environmental Impact 12 6. SUSTAINABILITY 12 6.1 Infrastructure 12 6.2 Equipment Maintenance 12 6.3 Cost Recovery 12 6.4 Health Staff 12 7. BANK’S AND BORROWER’S PERFORMANCE 13 7.1 Bank’s Performance 13 7.2 Borrower’s Performance 13 8. OVERALL PERFORMANCE AND RATING 13 9. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 13 9.1 Conclusions 13 9.2 Lessons 14 9.3 Recommendations 14 Mrs. B. BA (Public Health Expert) and a Consulting Architect prepared this report following their project completion mission in the Republic of Cote d’Ivoire on March-April 2000. -

A Characterization of the Soil Resource of the Research Station At

A CHARACTERIZATION OF THE SOIL RESOURCE OF THE RESEARCH STATION AT FERKESSEDOUGOU (NORTHERN COTE D 9 IVOIRE) WITH RESPECTS TO SUITABILITY OF IITA 9 S MAIZE SAVANNA SUBSTATION. Consultancy report for IITA, IBADAN, NIGERIA Christian VALENTIN Soil Scientist ORSTOM, B.P. V-51, ABIDJAN, COTE D'IVOIRE September 1988 A CHARACTERlZATlON OF THE SOIL RESOURCE OF THE RESEARCH STATION AT FERKESSEDOUGOU (NORTHERN COTE D'IVOIRE) WlTH RESPECTS TO SUITABlLlTY OF lITA'S MAIZE SAVANNA SUBSTATION. Christian VALENTIN I. INTRODUCTION In 1982, maize was the first cereal cropped in Côte d'Ivoire in terms of production (470,000 metric tons), before paddy (420,000 tons) ( MOYAL, 1988a). Due to the rapid growth of population, this production will have to be doubled before the end of the century. Research must therefore be strengthened for increased maize production. This meets the mandate of lITA (International Institute of Tropical Agriculture) which conducts research in partnership wi th the National Agricultural Research Services. One of its recently developed program strategies is to establish small research substations in the key ecological zones of West and Central Africa such as the moist savanna zone which includes almost 45 percent of the coastal West Africa, but only 30 percent of the population of the region. With a growing period ranging from 150 to 240 days, intense solar radiation during the growing season, this well-endowed region is supposed to have the greatest potential for future maize production. In order to deal adequately with the research priorities of this environment and to produce technological advances that are appropriate to the farming systems of the region, a research substation will have been established in this region by 1989. -

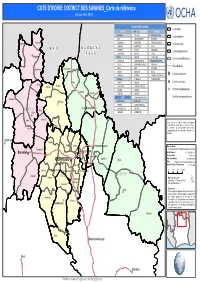

CIV0003 REF DISTRICT DES SAVANES Admin A3L 201200801

COTE D'IVOIRE: DISTRICT DES SAVANES_Carte de référence (Version Mars 2013) DISTRICT DES SAVANES Limite d'Etat BAGOUE KORHOGO TCHOLOGO BOUNDIALI BOUGOU FERKESSEDOUGOU Limite de district (! (! BAYA DASSOUNGBOHO BILIMONO Débété Papara BOUNDIALI KANOROBA FERKESSEDOUGOU Limite de région M A L I BUR KINA GANAONI KARAKORO KONG KASSERE KATIALI KOUMBALA Limite de département F A S O SIEMPURGO KATOGO SIKOLO H!(!Tengrela KOUTO KIEMOU TOGONIERE Limite de Sous-Préfecture BLESSEGUE KOMBOLOKOURA OUANGOLODOUGOU (! GBON KOMBORODOUGOU DIAWALA (! Route Bitumée Kanakono Toumoukoro BURKOLIA KINA KONI KAOUARA KOUTO KORHOGO NIELLE P! Chef-lieu de District SIANHALAF A S O LATAHA OUANGOLODOUGOU TENGRELA M'BENGUE TOUMOUKORO (! Nielle !! Chef-lieu de région (! DEBETE NAFOUN Blességué Bougou (! Katogo KANAKONO NAPIEOLEDOUGOU (! PAPARA NIOFOIN H! Chef-lieu de département Diawala (! Kaouara TENGRELA SIRASSO (! (! PORO TIORONIARADOUGOU Chef-lieu de sous-préfecture Sianhala(! M'Bengué DIKODOUGOU SINEMATIALI ! H!( BORON KAGBOLODOUGOU Ouangolodougou H!(! DIKODOUGOU SEDIOGO BAGOUE Baya GUIEMBE SINEMATIALI Kouto (! H!(! Gbon (! Kassere (! (! Cette carte a été réalisée selon le découpage Katiali administratif de la Côte d'Ivoire à partir du Décret Kolia(! n° 2011-263 du 28 septembre 2011 portant organisation du territoire national en Districts et en Régions Madinani Niofoin H! (! Koni Lataha FERKESSEDOUGOU (! (! H!(! !H(! Map Doc Name: Siempurgo CIV0003 REF DISTRICT DES SAVANES A3L 20130327 Sinematiali Boundiali !(! (! Sédiogo GLIDE Number: OT-2010-00255-CIV !H (! (! Creation -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Risk-sensitive Budget Review UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction UNDRR Country Reports on Public Investment Planning for Disaster Risk Reduction This series is designed to make available to a wider readership selected studies on public investment planning for disaster risk reduction (DRR) in cooperation with Member States. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) Country Reports do not represent the official views of UNDRR or of its member countries. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the author(s). Country Reports describe preliminary results or research in progress by the author(s) and are published to stimulate discussion on a broad range of issues on DRR. Funded by the European Union Front cover photo credit: Anouk Delafortrie, EC/ECHO. ECHO’s aid supports the improvement of food security and social cohesion in areas affected by the conflict. Page i Table of contents List of figures ....................................................................................................................................ii List of tables .....................................................................................................................................iii List of acronyms ...............................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgements ...........................................................................................................................v Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... -

J Savanes Vallée Du Bandama Worodougou Zanzan

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MA034 !Watiali Koulousson Doubasso ! ! Kebeni M A L I ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O Gongoro! Kapégué Sindou Sideradougou ! Kolonz!a Kokari ! Débété ! Papara ! ! Banfora Zanasso Basso !H ! ! ! ! IribassoTiongoli Diou TengrelaDiamankani ! ! Loumana G U I N E A ! Nigoni Kadiolo ! Féni ! ! Tamania Goindougouba ! ! Tientierimé! ! Baguera ! Zélésso ! ! ! Béniasso ! TENGRELA Nafegue ! ! Mbasso ! ! ! C Ô T E D ' I V O I R E Sirakoro Man!Hiasso Tia!laka Zegoua Dakoro Soubakaniedougou ! ! ! Sissingué ! ! ! Dafala BougoulaTiempa Naniasso ! ! Baviguekaha ! ! !Kotou Pogo ! !Kouroukoro ! Pourou ! ! G H A N A ! Kanakono Tiogo San ! Ouarga Missasso ! Kanakono Toumoukoro !Koron!ani ! Néguépié ! L I B E R I A Bossie ! Tiébi !Lomara Pongala Boulou ! ! ! !H ! ! Ouamélhoro Fourkoura ! Fimbiasso Popo Zanikan Misseni ! ! Bolona ! Nafoungo!lo ! ! ! NaléhoLouholo ! Mbélé Dougba Mibrigu!é ! ! ! ! !Kassérégué Kadarvogo Niangoloko T e n g rr é ll a Kokoroko ! ! ! !! Tokala Tianna ! !Sinakaha Mahand!iana-Sobala Sanoualé ! Gbéni Ngandana Nielle Somavog!o ! ! ! Bougou Kafokaha Gbinzo 1 Portio BlésséguéSingo ! Niéllé! ! ! ! ! ! ! Djélisso Ouassangalasso Tiogo Ka!fonon Séguébé Téhékaha Diéllé Natogo ! Zesso ! ! ! ! ! !H ! ! ! KantaraKatogo Kaniéné Nongon Niangbrass!o Tinpereba Ouo!mon ! ! ! ! Nalog!o ! Maha!lé ! Kakorogo ! ! Mahandougou ! ! Souhouo Nambira ! Tabakoroni ! Vononloho! Douasso Pouniakél!é Ouara Nétoulou ! ! Kassiongokoro SononiDiawala ! ! Koliani Zangbanou ! ! Tiaplé ! ! ! ! ! ! K!aouara Ninioro Zaguinasso Nidienkaha ! Tiétougou -

Côte D'ivoire Living Standards Survey (Cilss) 1985-88

The World Bank/ Institut National de la Statistique, Côte d'Ivoire CôTE D'IVOIRE LIVING STANDARDS SURVEY (CILSS) 1985-88 Basic information for users of the data August 6, 1996 c:\wp51\doc\cilss\cilss3.mv, js Contents I. Introduction .................................................................... 1 II. CILSS Questionnaires ........................................................... 3 The Household Questionnaire ................................................. 3 Community Questionnaire ................................................... 15 The Price Questionnaire ..................................................... 18 Health Facility Survey, 1987 ................................................. 21 III. Sample Design and Selection .................................................... 22 Sampling Procedures for Block 1 Data .......................................... 22 Sampling Procedures for Block 2 Data .......................................... 23 Bias in the Selection of Households within PSUs, Block 1 Data ...................... 23 Problems Due to Inaccurate Estimates of PSU Population ........................... 24 Classification of Clusters by Geographic Location ................................ 24 Non-Response and Replacement of Households ................................... 30 Selection of the Respondent for the Section on Fertility ............................ 31 IV. Survey Organization and Fieldwork .............................................. 32 Field-Testing of the Questionnaires Prior to Survey Implementation .................. -

DECRETE Article 1 : La Circonscription Électorale Constitue Le Référentiel Territorial De L'élection Des Députés À L'assemblée Nationale

PRESIDENCE DE LA REPUBLIQUE REPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D'IVOIRE Union - Discipline - Travail DECRET N° 2011-264 DU 28 SEPTEMBRE 2011 PORTANT DETERMINATION DES CIRCONSCRIPTIONS ELECTORALES POUR LA LEGISLATURE 2011-2016 LE PRESIDENT DE LA REPUBLIQUE, Sur rapport du Ministre d'Etat, Ministre de l'Intérieur, Vu la Constitution ; Vu la loi n° 2000-514 du 01 août 2000 portant Code Electoral; Vu la loi n° 2004-642 du 14 décembre 2004 modifiant la loi n02001-634 du 9 octobre 2001 portant composition, organisation, attributions et fonctionnement de la Commission Electorale Indépendante (CEl) telle que modifiée par les Décisions du Président de la République n02005-06/PR du 15 juillet 2005 et n02005-11 du 29 août 2005 relatives à la la Commission Electorale Indépendante; Vu la loi n° 61-84 du 10 avril 1961 relative au fonctionnement des Départements, des Préfectures et Sous-préfectures ; Vu la loi n° 69-241 du 9 juin 1969 portant découpage administratif de la République de Côte d'Ivoire; Vu l'ordonnance n° 2008-15/PR du 14 avril 2008 portant modalités spéciales d'ajustements au code électoral pour les élections de sortie de crise; Vu l'ordonnance n° 2008-133 du 14 avril 2008 portant ajustement au Code Electoral pour les élections de sortie de crise ; Vu l'ordonnance n° 2011-224 du 16 septembre 2011 fixant le nombre de sièges de Députés à l'Assemblée Nationale; Vu le décret n° 2010-01 du 04 décembre 2010 portant nomination du Premier Ministre; Vu le décret n° 2011-101 du 01 juin 2011 portant nomination des Membres du Gouvernement; Vu le décret n° 2011-118 du 22 juin 2011 portant attributions des Membres du Gouvernement, Le Conseil des Ministres entendu DECRETE Article 1 : La circonscription électorale constitue le référentiel territorial de l'élection des députés à l'Assemblée Nationale. -

Connaissances Locales Et Leur Utilisation Dans La Gestion Des Pares Akarite En Cote D'ivoire

AFRJ KA FOCUS -Volume 21, Nr.I, 2008 - pp. 77-96 Connaissances locales et leur utilisation dans la gestion des pares akarite en Cote d'Ivoire Nafan Diarassouba (1), Kouablan E. Koftl (1), Kanga A. N'Guessan (2), Patrick Van Damme (3), Abdourahamane Sangare (1) (1) Laboratoire Central de Biotechnologies (LCB) du Centre National de Recherche Agronomique de Cote d'Ivoire (2) Station de Recherche Kamonon Diabate, Direction regionale de Korhogo duCNRA (3) Laboratoire de l'Agronomie Tropicale et Subtropicale et d'Ethnobotanique, Universite de Gand In order to assess both the level of botanical knowledge of the shea tree species possessed by certain communities, and the relative importance of the species to those communities, an inven tory has been taken of the different uses of shea resources. To this end, research was conducted involving 257 people belonging to 12 different ethnic groups in seven departments ofthe north of the Cote d'Ivoire [Ivory Coast]. The results of these investigations clearly demonstrate the socio economic importance ofshea trees to the local populations of the zone investigated. Some ethnic groups prove to have a very good botanical knowledge of the species and its qualities and have developed systems of management of shea orchards that could facilitate the domestication and conservation of the species. In addition to the commercial use of the kernel and of shea butter on local and regional markets, many other parts of the shea tree and derived products (roots, leaves, peels, oilcakes, latexes and even mistletoes are used for a range of different purposes by rural communities in Cote d'Ivoire [the Ivory Coast].