A Better Future for Artists, Citizens and the State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 29 | Aug 2017 |

AN INDEPENDENT, FREE MONTHLY GUIDE TO MUSIC, ART, THEATRE, COMEDY, LITERATURE & FILM IN STROUD. ISSUE 29 | AUG 2017 | WWW.GOODONPAPER.INFO GOOD 2017 ON PAPER SPECIAL ISSUE #29 INSIDE: STROUD STROUD GOOD FRINGE BLOCK ON PAPER PREVIEW PARTY STAGE + Joe Magee: The Process | Stroud Fringe Choir | Index Projects: Corridor Burning House Books | Comedy At The Fringe Cover image: Ardyn by Adam Hinks (Original image by Tammy Lynn Photography) Lynn Tammy image by Hinks (Original Adam by image: Ardyn Cover #29 | AUG 2017 EDITOR Advertising/Editorial/Listings: EDITOR’S Alex Hobbis [email protected] DESIGNER Artwork and Design NOTE Adam Hinks [email protected] ONLINE FACEBOOK TWITTER goodonpaper.info /GoodOnPaperStroud @GoodOnPaper_ WELCOME TO THE TWENTY NINTH ISSUE OF GOOD ON PAPER – YOUR FREE MONTHLY GUIDE TO MUSIC CONCERTS, ART EXHIBITIONS, THEATRE PRINTED BY: PRODUCTIONS, COMEDY SHOWS, FILM SCREENINGS AND LITERATURE Tewkesbury Printing Company EVENTS IN STROUD... The fringe returns! And with it our annual Stroud Fringe Special providing a defi nitive guide to the 21st edition of the festival. SPONSORED BY: The team behind the fringe have worked tirelessly throughout the year to bring you another packed programme of events featuring live music, comedy, art, literature, street entertainment and much much more over the course of the last weekend in August. CO-WORKING STUDIO As well as the Bank Gardens, Canal and Cornhill stages the hugely popular Stroud Block Party also returns with a brand new venue, Good On Paper will be taking stroudbrewery.co.uk -

LCO Working with Us

LONDON CONTEMPORARY ORCHESTRA WORKING WITH US “...a grass-roots perspective and a wide-eyed enthusiasm that could only exist in an orchestra run by young people for young people.” Classical Music Magazine COLLABORATIONS | CORPORATE EVENTS | PRODUCT LAUNCHES London Contemporary Orchestra Limited 9 Angel Mews, London SW15 4HU, United Kingdom Company No: 6895875 Registered Charity No: 1129768 www.lcorchestra.co.uk www.lcorchestra.co.uk WHAT WE DO DIFFERENTLY • Formed in 2008, the LCO has already established itself as one of the most innovative and DYNAMIC. respected ensembles on the London music scene. CUTTING EDGE. • LCO has worked alongside such distinguished artists as Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, Matmos, Biosphere, composers Mark-Anthony Turnage and Anna Meredith, Sound Intermedia, Mira Calix, United Visual Artists, sound artist Simon Fisher Turner and Foals. • At all times we aim to stimulate and enlighten audiences through our fresh approach and breathtaking performances. • LCO draws together London’s brightest young talent – musicians who perform regularly with TALENTED. groups such as the London Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia YOUNG PROFESSIONALS. Orchestra and London Sinfonietta. • All our players possess an unrivalled technical facility to meet the demands of session work, and a friendly, open-minded approach crucial for collaborative projects. • Being on that level sets us apart on the London scene, creating events that always feel right and sound exceptional. • We can help with all your needs, including finding a suitable recording studio and liaising with VERSATILE. venues. LCO provides any number of players from a single harpist to a full symphony orchestra. WELL CONNECTED. We’ll also find you a particular soloist or chorus. -

Various Blech II: Blechsdöttir Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Blech II: Blechsdöttir mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Blech II: Blechsdöttir Country: UK Released: 1996 Style: IDM, Techno, Acid, Ambient, Breakbeat, Abstract, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1838 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1665 mb WMA version RAR size: 1507 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 339 Other Formats: AU AA DTS DMF VQF MP2 MOD Tracklist Hide Credits Lost 1a –Autechre 2:25 Written-By – Brown*, Booth* Kracht 1b –Disjecta Written-By – Mark Clifford Rotar 2a –Autechre 2:00 Written-By – Brown*, Booth* Flutter 2b –Autechre Written-By – Brown*, Booth* Them 3 –LFO 1:53 Written-By – Mark Bell Abla Eedio (Unreleased Exclusive Mix) 4 –Plaid 3:45 Written-By – Turner*, Handley* Ventolin (Plain-An-Gwaary Mix) 5 –Aphex Twin 3:30 Written-By – Richard D James* Rsdio 6 –Autechre 3:05 Written-By – Brown*, Booth* Nautilus 7 –Jake Slazenger 3:08 Written-By – Mike Paradinas Dredd Overboard (DJ Food Lifesaver Mix) 8a –Nightmares On Wax 3:38 Remix – DJ FoodWritten-By – Evelyn*, Harper*, Firth* Cow Cud Is A Twin 8b –Aphex Twin Written-By – Richard D James* Laughable Butane Bob 9 –AFX* 2:53 Written-By – Richard D James* Brieflei 10 –Freeform 3:04 Written-By – Simon Pyke Chase The Manhattan 11 –The Black Dog 1:26 Written-By – Turner*, Handley*, Downie* Inifinite Lites (Primitives Mix) 12 –B12 4:01 Written-By – Golding*, Rutter* Midnight Drive 13a –Elecktroids 2:49 Written-By – Elecktroids Hey Hey Can U Relate 13b –DJ Mink Written-By – Carruthers, Mink*, McDevitt Dextrous 13c –Nightmares On Wax Written-By – Evelyn*, Harper* -

Samedi 23 Septembre London Sinfonietta – Warp Records

NP WARP DEF 15/09/06 15:04 Page 1 Jean-Philippe Billarant, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Samedi 23 septembre London Sinfonietta – Warp Records Dans le cadre du cycle Londres Du mercredi 20 septembre au samedi 7 octobre 2006 | septembre 23 Samedi Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.cite-musique.fr London Sinfonietta – Warp Records – Warp Sinfonietta London NP WARP DEF 15/09/06 15:04 Page 2 Cycle Londres DU MERCREDI 20 SEPTEMBRE AU SAMEDI 7 OCTOBRE Londres : la ville de Purcell, de Haydn, de Britten, mais aussi l’un des berceaux MERCREDI 20 SEPTEMBRE, 20h de la pop, des Beatles à Marianne Faithfull et au-delà. Autour de l’intégrale des douze symphonies dites londoniennes de Haydn, Intégrale des Symphonies un instantané musical de la capitale anglaise, entre humour et solennité, londoniennes I tradition et modernité… Joseph Haydn Nombre de symphonies de Haydn portent des titres imagés, donnés après coup Symphonie no 103 par les chroniqueurs en référence à un motif de l’œuvre ou à un événement Symphonie no 102 qui en a marqué l’exécution. Les symphonies londoniennes ne font pas exception. Symphonie no 104 Toutefois, au-delà des anecdotes qu’elles ont pu susciter, c’est au sein de la grande histoire des formes musicales que ces pages ont laissé leur empreinte. Orchestra of the Age C’est de Londres, où il séjourna de 1791 à 1795, que Haydn rapporta un livret of Enlightenment qui avait d’abord été destiné à Haendel. -

Tim Joss First Published for Comment on the Web by Mission Models Money September 2008

A better future for artists, citizens and the state Tim Joss First published for comment on the web by Mission Models Money www.missionmodelsmoney.org.uk September 2008 Copyright © 2008 Tim Joss The moral right of Tim Joss to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed by Pointsize Wolffe & Co 2 New Flow Contents Prelude 4 Acknowledgements 5 Introduction 6 Chapter 1 UP-RIVER – Changes since the creation of the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1946 11 Chapter 2 THE SWIRL OF NOW – Wider forces in society which touch the arts 26 Chapter 3 POOH-STICKS OVER RAPIDS – Signs of change inside the arts 39 Chapter 4 TODAY’S ARTS FLOTILLA – Artists 59 Chapter 5 TODAY’S ARTS FLOTILLA – The accessibility industry 71 Chapter 6 THAT SINKING FEELING – The pathology of today’s state arts bodies 81 Chapter 7 NEW FLOW – New organisations 97 Chapter 8 NEW FLOW – Five years of travelling down-river 110 Postlude 115 Bibliography 116 3 New Flow Prelude This book’s key message is that artists have an important contribution to make to our society and economy. It is not being properly or fully realised. The task is to release artists’ potential to the full and achieve the most profound and far-reaching impact possible. This book is part arrival, part new departure. It proposes a way forward and invites you to be involved in the next steps. Written in the tradition of political pamphlets, it makes specific, practical proposals. -

NR 04/3 Citroengeel-Mira Calex

v.u. Jo Lijnen, Burg. Bollenstr. 54-56+, 3500 Hasselt BELGIE-BELGIQUE P. B. 3500 Hasselt 1 12/741 E E 3500-HASSELT BURG.BOLLENSTR.54-56+ KUNSTENCENTRUM 3500-HASSELT BURG.BOLLENSTR.54-56+ KUNSTENCENTRUM B B L L WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 WARP NIGHT-MIRACALIX (UK)-29mei‘04 G G I I E E ”NEW-RELEASES” / 14°jaargang / 5 X per jaar:jan.-mrt-mei-juli-okt/ editie:mei. 2004 Afgiftekantoor: 3500 Hasselt 1 - P 206555 ✯ ININ THETHE CUTCUT (AUS/USA/UK / 2003 / 120’ / 35 mm) Cast Meg Ryan, Mark Ruffalo, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Nick Damici, Regie: Jane Campion Sharrieff Pugh, Michael Nuccio, Alison Nega, Dominick Aries, Susan Gardner, Heather Litteer, Daniel T. Booth, Kevin Bacon Muziek Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson (zie Sigur Ros, Psychic TV, Current 93) Frannie (Meg Ryan) is een in zichzelf gekeerde, alleenstaande Engelse literatuur- docente die les geeft aan een middelbare school in Manhattens East Village. Behalve haar studie over het gebruik van slangwoorden bij jongeren en haar passie voor politieromans houdt ze zich ver van de donkere kant van het grootstadsleven. Tijdens een bezoek aan een bar is ze ongewild getuige van een intiem moment tussen een man en een vrouw. Verschrikt, maar evenzeer gefascineerd door de passie tussen deze twee vreemden, merkt ze slechts de zwoele blik en een tatoeage op van de man. Als er daags nadien een moord blijkt te zijn gepleegd in de buurt van Franny’s huis, wordt ze benaderd door detective Malloy (Mark Ruffalo), die vermoedt dat Franny meer weet. -

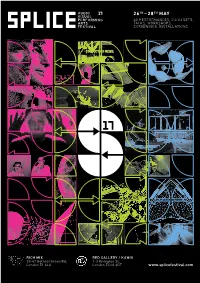

View Splice Programme 2017

RICH MIX RED GALLERY / KAMIO 35-47 Bethnal Green Rd, 1-3 Rivington St, London E1 6LA London EC2A 3DT www.splicefestival.com WORKSHOPS RESOLUME : BEGINNERS RESOLUME : ADVANCED OPTIKAL INK LAB : LED LAB & Welcome to Splice Festival - London’s dedicated WORKSHOP MASTERCLASS STAGE DESIGN THURSDAY 25TH MAY 13:00 – 16:00 / UAL / LCC FRIDAY 26TH MAY 15:00 – 17:00 / RICH MIX FRIDAY 26TH MAY 11:00 – 17:00 audio visual performing arts festival. We’re very & SATURDAY 27TH MAY 12:00 – 18:00 / From zero to hero in 3 hours. The The two founders of Resolume, Edwin RED GALLERY & KAMIO two founders of Resolume, Edwin de Koning and Bart van der Ploeg host happy to return for our second edition from This workshop is an initiation to de Koning and Bart van der Ploeg, an advanced masterclass at Rich Mix. LED mapping and stage design. LED th th host a beginners workshop at This workshop is for everyone who the 26 –28 May at multi-arts venues Rich Mix, mapping is a technique that uses LED University of the Arts, London College already has some experience with lighting technology and DMX/ArtNet of Communication. This workshop VJing in general, but wants to get protocols to design spaces, stages, Red Gallery and Kamio. teaches you all you need to know to inside the many options Resolume installations, performances, fashion start VJing with Resolume. They’ll has to offer. How to sync clips to the garments and more. On day one go over ‘what does what’ in the BPM or have effects ‘pop’ to the music, Splice Festival forms the UK branch of Creative Europe’s AV Node Network, a large participants will focus on the theory interface and show you the best ways using cue points and BeatLoopr to and on day two they will put theory scale project which partners 13 art and technology festivals across 12 European to use the software. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Electronic Music Gallery Program

ELECTRONIC MUSIC GALLERY 1 Credits DIRECTOR MICHAEL BLAKE Introduction The Electronic Music Gallery is a six-hour CURATOR exhibition tracing the history and COBI VAN TONDER development of electronic and electro acoustic music. Numerous international and South African composers’ and musicians’ ASSISTANT CURATOR works are featured, from the first pioneers to DIMITRI VOUDOURIS various contemporary artists. The origins of electronic music can be traced back to the audio analytical work of the PROGRAMMING OF OPEN GL GRAPHICS TEXT DISPLAY German physicist and mathematician, GERRIE ROOS Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (1821-1894), who built an electronically controlled instrument to analyse SOUND AND EQUIPMENT combinations of tones. Von Helmholtz was CORINNE COOPER not concerned with musical applications, but rather with the scientific analysis of sound. The first electronic instruments such as the PAMPHLET EDITOR AND DESIGNER Telharmonium and Chorelcello were created ALBERT SAPSFORD between 1870 and 1915. Thereafter, between 1915 and 1928, the Audion Piano, Theremin Sphäraphon, Pianorad and Ondes Martenot MUSIC SELECTED BY emerged. These instruments made use of the COBI VAN TONDER vacuum tube, a type of synthesis that was DIMITRI VOUDOURIS widely employed until the 1960’s, when the integrated circuit came into widespread use CHRIS WOOD and a new generation of easy to use, reliable and popular electronic instruments were created by Robert Moog, Donald Buchla and others. In the 1980’s the digital synthesiser was developed. It allowed complex control Contact details over various forms of synthesis previously available only on extremely expensive studio synthesisers. Examples of early digital Cobi Van Tonder / Otoplasma synthesisers are the Yamaha DX and the [email protected] Casio CZ. -

Issue 204 First Copy.Indd

nightshift @oxfordmusic.net nightshift .oxfordmusic.net Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 204 July Oxford’s Music Magazine 2012 GunningGunning ForFor TamarTamar Sonic fi repower, wristwatches and keeping it indie - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net CHARLBURY RIVERSIDE the club’s website, saying, he wanted FESTIVAL will take place over the to move closer to Oxford city centre. fi nal weekend of July after the original July’s line-up features Jim Suhler event in June was postponed due to & Monkeybeat on the 2nd, Bayou the risk of fl ooding. Brothers on the 9th, The Larry Miller The annual two-day free festival, Band on the 16th and Marcus Bonfanti FIXERS have released their debut album `We’ll Be The Moon’ on indie featuring a host of acts from across on the 23rd. label Dolphin Love after parting company with Mercury Records on the eve Oxfordshire, was due to take place on THE BULLINGDON will be of its intended release date. the 16th-17th June but days of heavy continuing to showcase the best blues The band had cancelled all dates on their UK tour, apart from their Oxford rain made the area alongside the sounds on a Monday however, with show at the O2 Academy, ahead of the announcement that they had left Evenlode river unsafe and further rain local blues-rock stalwart Tony Jezzard Mercury, prompting speculation about their future, but speaking to Nightshift threatened to fl ood the area. -

2005 Festivalio Organizatoriai: Pagrindiniai Rėmėjai Lietuvos Kompozitorių Sąjunga Ir Všį “Vilniaus Festivaliai” Festivalio Televizija

AKTUALIOS MUZIKOS FESTIVALIS GAIDAVilnius, spalio 12-28 2005 Festivalio organizatoriai: Pagrindiniai rėmėjai Lietuvos kompozitorių sąjunga ir VšĮ “Vilniaus festivaliai” Festivalio televizija Organized by the Lithuanian Composers’ Union and Public Enterprise “Vilnius Festivals” Didžiausias šalies dienraštis Festivalio dienraštis Didieji partneriai / Main partners: Festivalio viešbutis Jeigu įsiklausytume į miesto skambesį, suvoktume, kaip Informaciniai rėmėjai skirtingai skamba Vilnius keičiantis metų laikams. Jau penkiolika metų iš eilės rudens garsus papildo festivalis Partneriai / Partners: „Gaida“, kuris vilniečiams ir miesto svečiams pristato įspūdingą šiuolaikinės muzikos panoramą. Būtent tokie aukšto lygio kultūros įvykiai daro Vilnių ne tik Lietuvos, bet ir regiono centru, pasaulio miestu. Suomijos Respublikos ambasada Vilniuje Dėkoju festivalio „Gaida“ rengėjams už jų triūsą ir ištikimybę naujajai muzikai. Sveikinu visus dalyvius, The Foundation for the vilniečius ir miesto svečius su geros muzikos švente bei Promotion of Finnish Music Rėmėjai linkiu kuo geriausių įspūdžių! Festivalio repertuarinis komitetas / Repertoire Committee: Gražina Daunoravičienė, Rūta Gaidamavičiūtė, Rūta Goštautienė, Daiva Parulskienė, Vytautas Laurušas, Remigijus Merkelys, Šarūnas Nakas Organizacinė grupė / Executive Group: Remigijus Merkelys, Daiva Parulskienė, Živilė Stonytė, Paulius Jurgutis, Vytautas V. Jurgutis, Artūras Zuokas Vytautas Gailevičius, Linas Paulauskis Vilniaus miesto meras Bukleto sudarytoja ir redaktorė / Booklet compiler and editor -

Les Musiques Électroniques (10/10/2014)

Dossier d’accompagnement de la conférence-concert du vendredi 10 octobre 2014 en partenariat avec l’Aire Libre dans le cadre du programme d’éducation artistique et culturelle de l’ATM. Conférence-concert “LES MUSIQUES ÉLECTRONIQUES” Conférence de Pascal Bussy Concerts de Fragments // DJ Azaxx Déjà présente dans la musique classique et "contemporaine", l'électronique s'infiltre dans les "musiques actuelles" dès les années soixante par le biais de quelques expérimentateurs visionnaires. Elle intègre d'abord le rock, la pop, le rhythm’n’blues, la soul, le funk, le rap et la disco - elle est l’un des éléments moteurs de la dance music -, jusqu’au reggae et au jazz. A partir des années quatre-vingt, les musiques électroniques constituent une famille musicale à part entière. Afin de compléter la lecture de ce House, ambiant, techno, musique industrielle, "easy listening", electronica, dossier, n'hésitez pas à consulter dubstep etc., ses formes sont multiples. Grâce aux machines, de nouvelles les dossiers d’accompagnement générations de musiciens créent des musiques qui couvrent un spectre très des précédentes conférences- large, de la transe à l'abstraction, du très commercial à l'avant-garde la plus concerts ainsi que les “Bases de radicale. données” consacrées aux éditions Au cours de cette conférence, nous retracerons ces évolutions et nous 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, montrerons comment les progrès technologiques ont favorisé l'apparition de 2010, 2011, 2012 et 2013 des nouveaux instruments et révolutionné les méthodes de composition. Enfin, nous Trans, tous en téléchargement expliquerons que ces esthétiques souvent innovantes correspondent aussi à gratuit sur www.jeudelouie.com une culture spécifique, à des schémas économiques alternatifs, et à des comportements qui bouleversent les modèles en place.