Investigating New Models for Opera Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

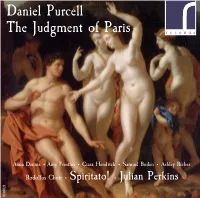

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

Rachmaninoff Symphony No

RACHMANINOFF SYMPHONY NO. 3 10 SONGS (ARR. JUROWSKI) VLADIMIR JUROWSKI conductor VSEVOLOD GRIVNOV tenor LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA SERGE RACHMANINOFF SYMPHONY NO. 3 Sir Henry Wood, writing in his autobiography My Life and conductor. If the public in Russia, Europe and America of Music (1938), predicted that Rachmaninoff’s Third recognised his gifts in all three branches of the profession, Symphony would ‘prove as popular as Tchaikovsky’s Fifth’. he himself always regarded himself as a composer first If that has never really been the case, Wood’s further and foremost. If he also happened to be one of the finest assessment of the score does ring true: pianists the world has ever known, that was, to a certain extent, a bonus. In 1917, however, there came a seismic ‘The work impresses me as being of the true Russian change in his life. With the onset and aftermath of the Romantic school. One cannot get away from the October Revolution, Rachmaninoff and his family felt beauty and melodic line of the themes and their logical compelled to emigrate. ‘Everything around me makes it development. As did Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff uses the impossible for me to work’, he wrote to his cousin and fellow instruments of the orchestra to their fullest effect. Those pianist Alexander Ziloti, ‘and I am frightened of becoming lovely little phrases for solo violin, echoed on the four solo completely apathetic. Everybody around me advises me to woodwind instruments, have leave Russia for a while. But where to, and how? And is it a magical effect in the slow movement. -

Commissioned Orchestral Version of Jonathan Dove’S Mansfield Park, Commemorating the 200Th Anniversary of the Death of Jane Austen

The Grange Festival announces the world premiere of a specially- commissioned orchestral version of Jonathan Dove’s Mansfield Park, commemorating the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen Saturday 16 and Sunday 17 September 2017 The Grange Festival’s Artistic Director Michael Chance is delighted to announce the world premiere staging of a new orchestral version of Mansfield Park, the critically-acclaimed chamber opera by composer Jonathan Dove and librettist Alasdair Middleton, in September 2017. This production of Mansfield Park puts down a firm marker for The Grange Festival’s desire to extend its work outside the festival season. The Grange Festival’s inaugural summer season, 7 June-9 July 2017, includes brand new productions of Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, Bizet’s Carmen, Britten’s Albert Herring, as well as a performance of Verdi’s Requiem and an evening devoted to the music of Rodgers & Hammerstein and Rodgers & Hart with the John Wilson Orchestra. Mansfield Park, in September, is a welcome addition to the year, and the first world premiere of specially-commissioned work to take place at The Grange. This newly-orchestrated version of Mansfield Park was commissioned from Jonathan Dove by The Grange Festival to celebrate the serendipity of two significant milestones for Hampshire occurring in 2017: the 200th anniversary of the death of Austen, and the inaugural season of The Grange Festival in the heart of the county with what promises to be a highly entertaining musical staging of one of her best-loved novels. Mansfield Park was originally written by Jonathan Dove to a libretto by Alasdair Middleton based on the novel by Jane Austen for a cast of ten singers with four hands at a single piano. -

Download PDF Booklet

THE CALL INTRODUCING THE NEXT GENERATION OF CLASSICAL SINGERS Martha Jones Laurence Kilsby Angharad Lyddon Madison Nonoa Alex Otterburn Dominic Sedgwick Malcolm Martineau piano our future, now Martha Jones Laurence Kilsby Angharad Lyddon Madison Nonoa Alex Otterburn Dominic Sedgwick THE CALL Martha Jones Laurence Kilsby Angharad Lyddon Madison Nonoa Alex Otterburn Dominic Sedgwick Malcolm Martineau THE CALL FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) 1 Fischerweise (Franz von Schlechta) f 2’53 2 Im Frühling (Ernst Schulze) a 4’32 ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) 3 Mein schöner Stern (Friedrich Rückert) d 2’39 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) 4 An eine Äolsharfe (Eduard Mörike) f 3’52 ROBERT SCHUMANN 5 Aufträge (Christian L’Egru) b 2’30 GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) 6 Le papillon et la fleur (Victor Marie Hugo) e 2’08 CLAUDE ACHILLE DEBUSSY (1862-1918) 7 La flûte de Pan (Pierre-Félix Louis) b 2’45 REYNALDO HAHN (1874-1947) 8 L’heure exquise (Paul Verlaine) c 2’27 CLAUDE ACHILLE DEBUSSY 9 C’est l’extase (Paul Verlaine) a 2’54 FRANCIS POULENC (1899-1963) Deux poèmes de Louis Aragon (Louis Aragon) d 10 i C 2’44 11 ii Fêtes galantes 0’57 GABRIEL FAURÉ 12 Notre amour (Armand Silvestre) e 1’58 MEIRION WILLIAMS (1901-1976) 13 Gwynfyd (Crwys) c 3’25 HERBERT HOWELLS (1892-1983) 14 King David (Walter de la Mare) b 4’51 RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) 15 The Call (George Herbert) f 2’12 16 Silent Noon (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) c 4’03 BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) 17 The Choirmaster’s Burial (Thomas Hardy) d 4’08 IVOR GURNEY (1890-1937) 18 Sleep (John Fletcher) e 2’55 BENJAMIN -

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List

Christopher Diffey – TENOR Repertoire List Leonard Bernstein Candide Role: Candide Volkstheater Rostock: Director Johanna Schall, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2016 A Quiet Place Role: François Theater Lübeck: Director Effi Méndez, Conductor Manfred Lehner 2019 Ludwig van Beethoven Fidelio Role: Jaquino Nationaltheater Mannheim 2017: Director Roger Vontoble, Conductor Alexander Soddy Georges Bizet Carmen Role: Don José (English) Garden Opera: Director Saffron van Zwanenberg 2013/2014 OperaUpClose: Director Rodula Gaitanou, April-May 2012 Role: El Remendado Scottish Opera: Conductor David Parry, 2015 (cover) Melbourne City Opera: Director Blair Edgar, Conductor Erich Fackert May 2004 Role: Dancaïro Nationaltheater Mannheim: Director Jonah Kim, Conductor Mark Rohde, 2019/20 Le Docteur Miracle Role: Sylvio/Pasquin/Dr Miracle Pop-Up Opera: March/April 2014 Benjamin Britten Peter Grimes Role: Peter Grimes (cover) Nationaltheater Mannheim: Conductor Alexander Soddy, Director Markus Dietz 2019/20 A Midsummer Night’s Dream Role: Lysander (cover) Garsington Opera: Conductor Steauart Bedford, Director Daniel Slater June-July 2010 Francesco Cavalli La Calisto Role: Pane Royal Academy Opera: Dir. John Ramster, Cond. Anthony Legge, May 2008 Gaetano Donizetti Don Pasquale Role: Ernesto (English) English Touring Opera: Director William Oldroyd, Conductor Dominic Wheeler 2010 Lucia di Lammermoor Role: Normanno Nationaltheater Mannheim 2016 Jonathan Dove Swanhunter Role: Soppy Hat/Death’s Son Opera North: Director Hannah Mulder, Conductor Justin Doyle April -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Issue 29 | Aug 2017 |

AN INDEPENDENT, FREE MONTHLY GUIDE TO MUSIC, ART, THEATRE, COMEDY, LITERATURE & FILM IN STROUD. ISSUE 29 | AUG 2017 | WWW.GOODONPAPER.INFO GOOD 2017 ON PAPER SPECIAL ISSUE #29 INSIDE: STROUD STROUD GOOD FRINGE BLOCK ON PAPER PREVIEW PARTY STAGE + Joe Magee: The Process | Stroud Fringe Choir | Index Projects: Corridor Burning House Books | Comedy At The Fringe Cover image: Ardyn by Adam Hinks (Original image by Tammy Lynn Photography) Lynn Tammy image by Hinks (Original Adam by image: Ardyn Cover #29 | AUG 2017 EDITOR Advertising/Editorial/Listings: EDITOR’S Alex Hobbis [email protected] DESIGNER Artwork and Design NOTE Adam Hinks [email protected] ONLINE FACEBOOK TWITTER goodonpaper.info /GoodOnPaperStroud @GoodOnPaper_ WELCOME TO THE TWENTY NINTH ISSUE OF GOOD ON PAPER – YOUR FREE MONTHLY GUIDE TO MUSIC CONCERTS, ART EXHIBITIONS, THEATRE PRINTED BY: PRODUCTIONS, COMEDY SHOWS, FILM SCREENINGS AND LITERATURE Tewkesbury Printing Company EVENTS IN STROUD... The fringe returns! And with it our annual Stroud Fringe Special providing a defi nitive guide to the 21st edition of the festival. SPONSORED BY: The team behind the fringe have worked tirelessly throughout the year to bring you another packed programme of events featuring live music, comedy, art, literature, street entertainment and much much more over the course of the last weekend in August. CO-WORKING STUDIO As well as the Bank Gardens, Canal and Cornhill stages the hugely popular Stroud Block Party also returns with a brand new venue, Good On Paper will be taking stroudbrewery.co.uk -

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 2013: the Year in Brief

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 2013: The year in brief The 2013 Festival was one of Glydebourne’s Journey into cyberspace most ambitious, showcasing six highly Months before the Festival itself, diverse operas. Glyndebourne’s auditorium was the Ariadne auf Naxos was a choice prompted venue for the world premiere of our latest by Music Director Vladimir Jurowski, community opera, Imago*. Our education who, in his last season at Glyndebourne, department commissioned the work, in longed to tackle his first staged opera partnership with Scottish Opera, from by Richard Strauss. Katharina Thoma composer Orlando Gough and librettist directed, making her Glyndebourne debut. Stephen Plaice. The two-act piece brought Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie, directed by together over 75 local amateur singers Jonathan Kent, continued Glyndebourne’s (ranging in age from 15 to 73) working with exploration of Baroque operas less well- professional soloists as well as 25 young known in the UK – an interest shared by musicians in the pit with members of conductor William Christie. Don Pasquale Aurora Orchestra. by Donizetti was revived by Mariame Likened to a ‘La bohème for the digital age,’ Clément with a cast including Danielle Imago tells how a wheelchair-bound woman de Niese and Alessandro Corbelli. For the of 80, confined to a care home, creates an Britten centenary, Billy Budd was an obvious 18 year old avatar through whom she can selection. Falstaff and Le nozze di Figaro made re-experience the joys – and uncertainties – welcome returns. of youth. All perfectly suited Glyndebourne’s 1,200- The first performance, on 6 March, was seat auditorium. -

NSF Programme Book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1

two weeks of world-class music newbury spring festival 11–25 may 2019 £5 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1 A Royal Welcome HRH The Duke of Kent KG Last year was very special for the Newbury Spring Festival as we marked the fortieth anniversary of the Festival. But following this anniversary there is some sad news, with the recent passing of our President, Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon. Her energy, commitment and enthusiasm from the outset and throughout the evolution of the Festival have been fundamental to its success. The Duchess of Kent and I have seen the Festival grow from humble beginnings to an internationally renowned arts festival, having faced and overcome many obstacles along the way. Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon, can be justly proud of the Festival’s achievements. Her legacy must surely be a Festival that continues to flourish as we embark on the next forty years. www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk 1 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 2 Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon MBE Founder and President 1935 - 2019 2 box office 0845 5218 218 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 3 The Festival’s founder and president, Jeanie Countess of Carnarvon was a great and much loved lady who we will always remember for her inspirational support of Newbury Spring Festival and her gentle and gracious presence at so many events over the years. Her son Lord Carnarvon pays tribute to her with the following words. My darling mother’s lifelong interest in the arts and music started in her childhood in the USA. -

Don Giovanni Was Made Possible by a Generous Gift from the Richard and Susan Braddock Family Foundation, and Sarah and Howard Solomon

donWOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZARTgiovanni conductor Opera in two acts Fabio Luisi Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte production Michael Grandage Saturday, October 22, 2016 PM set and costume designer 1:00–4:30 Christopher Oram lighting designer Paule Constable choreographer Ben Wright revival stage director Louisa Muller The production of Don Giovanni was made possible by a generous gift from the Richard and Susan Braddock Family Foundation, and Sarah and Howard Solomon Additional funding was received from Jane and Jerry del Missier and Mr. and Mrs. Ezra K. Zilkha general manager Peter Gelb The revival of this production is made possible music director emeritus by a gift from Rolex James Levine principal conductor Fabio Luisi 2016–17 SEASON The 556th Metropolitan Opera performance of WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S don giovanni conductor Fabio Luisi in order of vocal appearance leporello maset to Adam Plachetka Matthew Rose donna anna Hibla Gerzmava continuo David Heiss, cello don giovanni Howard Watkins*, Simon Keenlyside harpsichord the commendatore mandolin solo Kwangchul Youn Joyce Rasmussen Balint don ot tavio Paul Appleby* donna elvir a Malin Byström zerlina Serena Malfi Saturday, October 22, 2016, 1:00–4:30PM This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, The Neubauer Family Foundation. Global sponsorship of The Met: Live in HD is also provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Musical -

LCO Working with Us

LONDON CONTEMPORARY ORCHESTRA WORKING WITH US “...a grass-roots perspective and a wide-eyed enthusiasm that could only exist in an orchestra run by young people for young people.” Classical Music Magazine COLLABORATIONS | CORPORATE EVENTS | PRODUCT LAUNCHES London Contemporary Orchestra Limited 9 Angel Mews, London SW15 4HU, United Kingdom Company No: 6895875 Registered Charity No: 1129768 www.lcorchestra.co.uk www.lcorchestra.co.uk WHAT WE DO DIFFERENTLY • Formed in 2008, the LCO has already established itself as one of the most innovative and DYNAMIC. respected ensembles on the London music scene. CUTTING EDGE. • LCO has worked alongside such distinguished artists as Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, Matmos, Biosphere, composers Mark-Anthony Turnage and Anna Meredith, Sound Intermedia, Mira Calix, United Visual Artists, sound artist Simon Fisher Turner and Foals. • At all times we aim to stimulate and enlighten audiences through our fresh approach and breathtaking performances. • LCO draws together London’s brightest young talent – musicians who perform regularly with TALENTED. groups such as the London Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia YOUNG PROFESSIONALS. Orchestra and London Sinfonietta. • All our players possess an unrivalled technical facility to meet the demands of session work, and a friendly, open-minded approach crucial for collaborative projects. • Being on that level sets us apart on the London scene, creating events that always feel right and sound exceptional. • We can help with all your needs, including finding a suitable recording studio and liaising with VERSATILE. venues. LCO provides any number of players from a single harpist to a full symphony orchestra. WELL CONNECTED. We’ll also find you a particular soloist or chorus.