A Bloody War and a Sickly Season

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and Life in the West Coast Reserve Fleet, 1913-1918

Canadian Military History Volume 19 Issue 1 Article 2 2010 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Richard O. Mayne "“For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918." Canadian Military History 19, 1 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 “For God’s Sake send help” HMCS Galiano, Pacific Navigation and life in the West Coast Reserve fleet, 1913-1918 Richard O. Mayne n 30 October 1918, Arthur for all activities related to Canada’s Ashdown Green, a wireless Abstract: HMCS Galiano is remembered oceans and inland waters including O mainly for being the Royal Canadian operator on Triangle Island, British Navy’s only loss during the First World the maintenance of navigation Columbia, received a bone-chilling War. However, a close examination aids, enforcement of regulations signal from a foundering ship. of this ship’s history not only reveals and the upkeep of hydrographical “Hold’s full of water,” Michael John important insights into the origins and requirements. Protecting Canadian identity of the West Coast’s seagoing Neary, the ship’s wireless operator sovereignty and fisheries was also naval reserve, but also the hazards and desperately transmitted, “For God’s navigational challenges that confronted one of the department’s key roles, Sake send help.” Nothing further the men who served in these waters. -

A HISTORY of GARRISON CALGARY and the MILITARY MUSEUMS of CALGARY

A HISTORY OF GARRISON CALGARY and The MILITARY MUSEUMS of CALGARY by Terry Thompson 1932-2016 Terry joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1951, where he served primarily as a pilot. Following retirement in 1981 at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, he worked for Westin Hotels, the CBC for the 1984 Papal visit, EXPO 86, the 1988 Winter Olympic Games and the 1990 Goodwill Games. Following these busy years, he worked in real estate and volunteered with the Naval Museum of Alberta. Terry is the author of 'Warriors and the Battle Within'. CHAPTER EIGHT THE ROYAL CANADIAN NAVY In 2010, the Royal Canadian Navy celebrated its 100th anniversary. Since 1910, men and women in Canada's navy have served with distinction in two World Wars, the Korean conflict, the Gulf Wars, Afghanistan and Libyan war and numerous peace keeping operations since the 1960s. Prior to the 20th Century, the dominions of the British Empire enjoyed naval protection from the Royal Navy, the world's finest sea power. Canadians devoted to the service of their country served with the RN from England to India, and Canada to Australia. British ships patrolled the oceans, protecting commerce and the interests of the British Empire around the globe. In the early 1900s, however, Germany was threatening Great Britain's dominance of the seas, and with the First World War brewing, the ships of the Royal Navy would be required closer to home. The dominions of Great Britain were now being given the option of either providing funding or manpower to the Royal Navy, or forming a naval force of their own. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

Captain John Denison, D.S.O., R.N. Oct

No. Service: Rank: Names & Service Information: Supporting Information: 27. 1st 6th Captain John Denison, D.S.O., R.N. Oct. Oct. B. 25 May 1853, Rusholine, Toronto, 7th child; 5th Son of George Taylor Denison (B. 1904 1906. Ontario, Canada. – D. 9 Mar 1939, 17 Jul 1816, Toronto, Ontario, Canada -D. 30 Mason Toronto, York, Ontario, Canada. B. May 1873, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) [Lawyer, 1 Oct 1904 North York, York County, Ontario, Colonel, General, later minister of Church) and Canada. (aged 85 years). Mary Anne Dewson (B. 24 May 1817, Enniscorthy, Ireland -D. 1900, Toronto, 1861 Census for Saint Patrick's Ontario, Canada). Married 11 Dec 1838 at St Ward, Canada West, Toronto, shows James Church. Toronto, Canada John Denison living with Denison family aged 9. Canada Issue: West>Toronto. In all they had 11 children; 8 males (sons) and 3 It is surmised that John Denison females (daughters). actually joined the Royal Navy in 18 Jul 1878 – John Denison married Florence Canada. Ledgard, B. 12 May 1857, Chapel town, 14 May 1867-18 Dec 1868 John Yorkshire, -D. 1936, Hampshire, England. Denison, aged 14 years, attached to daughter of William Ledgard (1813-1876) H.M.S. “Britannia” as a Naval Cadet. [merchant] and Catherina Brooke (1816-1886) “Britannia” was a wooden screw st at Roundhay, St John, Yorkshire, England. Three decker 1 rate ship, converted to screw whilst still on her stocks. Issue: (5 children, 3 males and 2 females). Constructed and launched from 1. John Everard Denison (B. 20 Apr 1879, Portsmouth Dockyard on 25 Jan Toronto, Ontario, Canada - D. -

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 72, Autumn 2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… The Kingston-class Maritime Coastal Defence Vessel (MCDV) HMCS Whitehorse conducts maneuverability exercises off the west coast. NAVAL ASSOCIATION OF CANADA ASSOCIATION NAVALE DU CANADA (See: “One Navy and the Naval Reserve” beginning on page 9.) Royal Canadian Navy photo. Starshell ISSN-1191-1166 In this edition… National magazine of the Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada From the Editor 4 www.navalassoc.ca From the Front Desk 4 PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh NAC Regalia Sales 5 HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele From the Bridge 6 PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] Maritime Affairs: “Another Step Forward” 8 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] One Navy and Naval Reserve 9 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] NORPLOY ‘74 12 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] Mail Call 18 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. Alec Douglas, [email protected] The Briefing Room 18 HONORARY COUNSEL • Donald Grant, [email protected] Schober’s Quiz #69 20 ARCHIVIST • Fred Herrndorf, [email protected] This Will Have to Do – Part 9 – RAdm Welland’s Memoirs 20 AUSN LIAISON • Fred F. -

In Peril on the Sea – Episode Two Chapter 1Part 1

In Peril on the Sea – Episode Two Chapter 1Part 1 CANADA AND THE SEA: 1600 - 1918 Flagship of the Fleet: The Old "Nobbler" An armoured cruiser, HMCS Niobe was commissioned in the RN in 1898 and transferred to the infant Canadian Naval Service in 1910. She displaced 11,000 tons, carried a crew of 677 and was armed with sixteen 6-inch guns, twelve 12-pdr. guns, five 3-pdr. quick-firing guns and two 18-inch torpedo tubes. Despite the British penchant for naming major warships after dis- tinguished admirals or figures from classical mythology, sailors had their own, much less glamorous, nicknames for their vessels and Niobe was always "Nobbler" to her crew. Niobe served until 1920 when she was sold for scrap. (Courtesy, National Archives of Canada, PA 177136) At sea, Sunday, 13 September 1942 The burial service took place on the quarterdeck just before sunset. The sky was overcast with a definite threat of rain but only a moderate sea was running and the wind force was just 3 or about 10 miles per hour. All members of the crew of the destroyer HMCS Ottawa not on watch were in at- tendance in pusser rig, their best dress, although the commanding -officer, Lieutenant Commander Clark Rutherford, RCN, remained on the bridge. The convoy he was escorting, ON 127 out of Lough Foyle in Ireland bound for Halifax, had lost seven merchantmen in the last three days, and though the arrival of air cover from Newfoundland that morning was cause for optimism, the danger was far from over. -

Betrayed Studies in Canadian Military History

Betrayed Studies in Canadian Military History The Canadian War Museum, Canada’s national museum of military history, has a three- fold mandate: to remember, to preserve, and to educate. It does so through an interlocking and mutually supporting combination of exhibitions, public programs, and electronic outreach. Military history, military historical scholarship, and the ways in which Canad- ians see and understand themselves have always been closely intertwined. Studies in Can- adian Military History builds on a record of success in forging those links by regular and innovative contributions based on the best modern scholarship. Published by UBC Press in association with the Museum, the series especially encourages the work of new genera- tions of scholars and the investigation of important gaps in the existing historiography, pursuits not always well served by traditional sources of academic support. The results produced feed immediately into future exhibitions, programs, and outreach efforts by the Canadian War Museum. It is a modest goal that they feed into a deeper understanding of our nation’s common past as well. 1 John Griffith Armstrong, The Halifax Explosion and the Royal Canadian Navy: Inquiry and Intrigue 2 Andrew Richter, Avoiding Armageddon: Canadian Military Strategy and Nuclear Weapons, 1950-63 3 William Johnston, A War of Patrols: Canadian Army Operations in Korea 4 Julian Gwyn, Frigates and Foremasts: The North American Squadron in Nova Scotia Waters, 1745-1815 5 Jeffrey A. Keshen, Saints, Sinners, and Soldiers: Canada’s Second World War 6 Desmond Morton, Fight or Pay: Soldiers’ Families in the Great War 7 Douglas E. Delaney, The Soldiers’ General: Bert Hoffmeister at War 8 Michael Whitby, ed., Commanding Canadians: The Second World War Diaries of A.F.C. -

Rnshs Virtual Plaque Series: H.M.C.S

RNSHS VIRTUAL PLAQUE SERIES: H.M.C.S. NIOBE’S ARRIVAL IN HALIFAX 1910 1 H.M.C.S. NIOBE’S ARRIVAL IN HALIFAX, 21 OCTOBER 1910 Through the first three decades after Confederation most Canadians assumed that they had no need of a navy of their own. With their Arctic waters safeguarded by ice and the Atlantic and Pacific coasts patrolled by vessels of the Royal Navy, Canada could concentrate on such land-based objectives as settlement of the prairie West and development of an urban-industrial core elsewhere. The only exception to this inward-looking orientation was provided by the Department of Marine and Fisheries (DMF), which operated several inshore patrol vessels designated to protect Canadian fishing grounds from American encroachment and also maintain the lighthouses and other aids to navigation strung along both our salt and fresh water shores. The decisive factor transforming benign neglect into vigorous self-assertion with respect to naval matters was the shifting balance of power at sea in Europe. By 1902 British assumptions about their capacity to maintain that nation’s status as the world’s preeminent naval power were in retreat. Con- struction of ever more formidable high seas fleets by the United States, Japan and especially Germany, forced the London government to reassess its naval strategy. In 1906 fleet consolidation in home waters brought about the abandonment of Halifax as an imperial military base and led to virtual elimi- nation of the Royal Navy’s peacetime presence in Canadian waters. Admiralty planners, despairing of Canadian assistance, had begun to assume that if war broke out protection of the sea approaches to Canada would have to be assigned to vessels of the American and Japanese navies. -

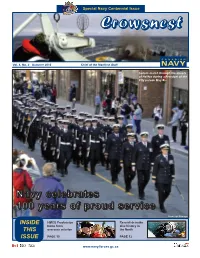

Crowsnest Issue 4-2.Qxd

Special Navy Centennial Issue CCrroowwssnneesstt Vol. 4, No. 2 Summer 2010 Chief of the Maritime Staff Sailors march through the streets of Halifax during a Freedom of the City parade May 4. NNaavvyy cceelleebbrraatteess 110000 yyeeaarrss ooff pprroouudd sseerrvviiccee Photo: Cpl Rick Ayer INSIDE HMCS Fredericton Reservists make home from dive history in THIS overseas mission the North ISSUE PAGE 10 PAGE 12 www.navy.forces.gc.ca Committing to the next 100 years he navy is now 100 years old. Under the authority of the Naval Services Act, the T Canadian Naval Service was created May 4, 1910. In August 1911 it was designated the Royal Canadian Navy by King George V until 1968 when it became Maritime Command within the Canadian Armed Forces. During the navy’s first century of service, Canada sent 850 warships to sea under a naval ensign. To mark the navy’s 100th anniversary, Canadian Naval Centennial (CNC) teams in Halifax, Ottawa, Esquimalt, 24 Naval Reserve Divisions across the Photo: MCpl Serge Tremblay country, and friends of the navy created an exciting Chief of the Maritime Staff Vice-Admiral Dean McFadden, program of national, regional and local events with left; Marie Lemay, Chief Executive Officer of the National the goal of bringing the navy to Canadians. Many of Capital Commission (NCC); and Russell Mills, Chair of these events culminated May 4, 100 years to the day the NCC’s Board of Directors, participate in a sod-turning that Canada’s navy was born. ceremony May 4 for the Canadian Navy Monument to be The centennial slogan, “Commemorate, Celebrate, built at Richmond Landing behind Library and Archives Commit”, reflects on a century of proud history, the Canada on the Ottawa River. -

Security, Sovereignty, and the Making of Modern Statehood in the British Empire, 1898-1931

The Widening Gyre: Security, Sovereignty, and the Making of Modern Statehood in the British Empire, 1898-1931 Author: Jesse Cole Tumblin Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:106940 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2016 Copyright is held by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0). THE WIDENING GYRE: SECURITY, SOVEREIGNTY, AND THE MAKING OF MODERN STATEHOOD IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE, 1898-1931 Jesse Cole Tumblin A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Boston College Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences Graduate School March 2016 © Copyright 2016 Jesse Cole Tumblin THE WIDENING GYRE: SECURITY, SOVEREIGNTY, AND THE MAKING OF MODERN STATEHOOD IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE, 1898-1931 Jesse Cole Tumblin Advisor: James E. Cronin, PhD This project asks why changing norms of statehood in the early twentieth century produced extraordinary violence, and locates the answer in the way a variety of actors across the British Empire—colonial and Dominion governments, nationalist movements, and clients or partners of colonial regimes—leveraged the problem of imperial defense to serve their own political goals. It explores how this process increasingly bound ideas about sovereignty to the question of security and provoked militarizing tendencies across the British world in the early twentieth century, especially among liberal governments in Britain and the colonies, which were nominally opposed to militarism and costly military spending. -

Of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra's

Index of Deaths in Service of Royal Naval Medical, Dental, Queen Alexandra’s Royal Naval Nursing Service, Sick Berth Staff and Voluntary Aid Detachment Staff World War I Researched and collated by Eric C Birbeck MVO and Peter J Derby - Haslar Heritage Group. Ranks and Rate abbreviations can be found at the end of this document Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Name Rank / Rate Off No 1 Date burial / memorial details (where known). Abbs TW SBA M4398 22/09/1914 HMS Aboukir (1900). Cressy-class armoured cruiser. Sank by U-9 off the Dutch coast. 2Along with: Surgeon Hopps, SBSCPO Hester, SBS Foley, 1 Officers’ official numbers are not shown as they were not recorded on the original documents researched. Where found, notes on awards and medals have been added. Ship, (Pennant No), Type, Reason for loss and other comrades lost and Name Rank / Rate Off No 1 Date burial / memorial details (where known). Hogan & Johnston and SBS2 Keily. Addis JW SBSCPO 150412 18/12/1914 HMS Grafton (1892). An Edgar-class cruiser. Died of illness Allardyce WS P/Surgeon 21/12/1916 HMS Negro. M-class destroyer. Sank from accidental collision with HMS Hoste in the North Sea.3 Allen CE Jnr RNASBR M9277 25/01/1918 HMS Victory. RN Barracks, Portsmouth. Died of illness. Anderson WE Snr RNASBR M10066 30/10/1914 HMHS Rohilla. Hospital Ship that ran aground and wrecked near Whitby whilst en route from Southampton to Scarpa Flow. Along with 22 other medical personnel (see notes at SBA Vine). -

1 Selection and Early Career Education of Executive Officers In

Selection and Early Career Education of Executive Officers in the Royal Navy c1902-1939 Submitted by Elinor Frances Romans, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Maritime History, March 2012. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature……………………………………………………………….. 1 This thesis is dedicated to the teachers who inspired me and, in the true sense of the word, educated me. I’d like to name you all but it would be a very long list. Without you this thesis would have been unthinkable. This thesis is dedicated to the colleagues, friends, phriends, DMers and DMRPers without whom it would have unendurable . This thesis is dedicated to my supervisor, Nicholas Rodger, without whom it would have been implausible. Above all though it is dedicated to my family, without whom it would have been impossible. 2 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the selection and early career education of executive branch officers in the Royal Navy c1902-1939. The thesis attempts to place naval selection and educational policy in context by demonstrating how it was affected by changing naval requirements, external political interference and contemporary educational reform. It also explores the impact of the First World War and the Invergordon mutiny upon officer education.