Knowledge in Parliamentary Debates"SUBJECT "JLP, Volume 1:2"KEYWORDS "Author to Provide"SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4">

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitution-Making and Reform: Options for the Process

Constitution-making and Reform Options for the Process Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, and Anthony Regan Title Constitution-making and Reform: Options for the Process Authors Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, Anthony Regan Date November 2011 Publisher Interpeace ISBN 978-2-8399-0871-9 Printed in Switzerland Copyright © Interpeace 2011. All rights reserved. Reproduction of figures or short excerpts from this report is authorized free of charge and without formal written permission, provided that the original source is properly acknowledged, with mention of the complete name of the report, the publisher, and the numbering of the pages or figures. Permission can be granted only to use the material exactly as it is in the report. Figures may not be altered in any way, including the full legends. For media use it is sufficient to cite the source while using the original graphic or figure. This is an Interpeace publication. Interpeace’s publications do not reflect any specific national or political interest. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of Interpeace. For additional permissions or information please e-mail [email protected]. About Interpeace Interpeace has been enabling societies to build lasting peace since 1994. Interpeace is an independent, international peacebuilding organization and a strategic partner of the United Nations. It supports national teams in countries across Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe, and the Middle East. Interpeace also has a thematic program on constitution-making. Over 300 peacebuilding experts work to help their societies manage their internal divisions and conflicts without resorting to violence or coercion. -

Constitution Constitution of Canada Du Canada

SENATE SÉNAT HOUSE OF COMMONS CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES Issue No.9 Fascicule n.9 Thursday, November 20, 1980 Le jeudi 20 novembre 1980 Joint Chairmen: Coprésidents: Sen¡tor Harry Hays Sénateur Harry Hays Serge Joyal, M.P. Serge Joyal, député Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence P rocès - ve rbaux et t émoi gnages of the Special Joint Committee of du Comité mixte spécial the Senate and of du Sénat et de the House of Commons on the la Chambre des communes sur la Constitution Constitution of Canada du Canada RESPECTING: CONCERNANT: The document entitled "Proposed Resolution for a Le document intitulé <Projet de résolution portant Joint Address to Her Majesty the eueen adresse commune à Sa Majesté la Reine respecting the Constitution of Canada" published concernant la Constitution du Canadar, publié par by the Government on October 2,1980 le gouvernement le 2 octobre 1980 iforme edela WITNESSES: TEMOINS: (See back cover) (Voir à l'endos) First Session of the Première session de la Thirty-second Parliament, 1 980 trente-deuxième législature, I 980 I 0s9 SPECIAL JOINT COMMITTEE OF COMITÉ MIXTE SPÉCIAL DU SÉNAT THE SENATE AND OF THE HOUSE ET DE LA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES OF COMMONS ON THE CONSTITUTION SUR LA CONSTITUTION DU CANADA OF CANADA Joint Chairmen; Coprésidents: Senator'Harry Hays Sénateur Harry Hays Serge Joyal, M.P. Serge Joyal, député Re pres e nt i ng t he S e nat e: Représentant le Sénat: Senators: Les sénateurs: Austin Haidasz Muir Rousseau Bielish Lapointe Nieman Tremblay-( l0) Bird Representing the House of Commons: Représentant la Chambre des communes: Messrs. -

1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY of SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS and RELATED MATTERS 3

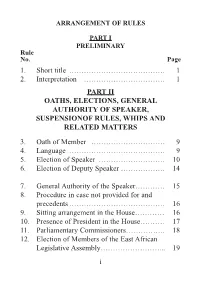

ARRANGEMENT OF RULES PART I PRELIMINARY Rule No. Page 1. Short title………………………………… 1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY OF SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS AND RELATED MATTERS 3. Oath of Member ………………………… 9 4. Language ………………………………… 9 5. Election of Speaker ……………………… 10 6. Election of Deputy Speaker ……………… 14 7. General Authority of the Speaker………… 15 8. Procedure in case not provided for and precedents………………………………… 16 9. Sitting arrangement in the House………… 16 10. Presence of President in the House………. 17 11. Parliamentary Commissioners……………. 18 12. Election of Members of the East African Legislative Assembly……………………... 19 i Rule No. Page 13. Election of Members of Pan African Parliament………………………………… 20 14. Role and functions of the Leader of the Opposition ………………………… 20 15. Whips……………………………………… 21 16. Suspension of Rules ……………………… 23 PART III MEETINGS, SITTINGS AND ADJOURNMENT OF THE HOUSE 17. Meetings ………………………………… 24 18. Emergency meetings……………………… 24 19. Sittings of the House……………………… 24 20. Suspension of sittings and recall of House from adjournment ………………… 25 21. Request for recall of Parliament from recess 26 22. Public holidays …………………………… 26 23. Sittings of the House to be public………... 26 24. Quorum of Parliament …………………… 27 PART IV ORDER OF BUSINESS 25. Order of business ………………………… 29 26. Procedure of Business …………………… 31 ii Rule No. Page 27. Order Paper to be sent in advance to Members ………………………………… 32 28. Statement of business by Leader of Government Business …………………… 33 29. Weekly Order Paper ……………………… 33 PART V PETITIONS 30. Petitions…………………………………… 34 PART VI PAPERS 31. Laying of Papers ………………………… 37 32. Mode of Laying of Papers………………… 37 PART VII PRESENTATION OF REPORTS OF PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATIONS ABROAD 33. -

The Parliamentary Calendar

7 The parliamentary calendar The appointment of the times for the holding of sessions of Parliament, the prorogation of the Parliament and the dissolution of the House, is a matter for decision by the Governor- General. The Constitution states: The Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, and may also from time to time, by Proclamation or otherwise, prorogue the Parliament, and may in like manner dissolve the House of Representatives.1 In practice however these vice-regal prerogatives are exercised with the advice of the Executive Government.2 Once a Parliament (session), or a further session within that Parliament, has commenced, the days and times for the routine meetings and adjournments of the House are a matter for the House to decide. Yet in practice, by virtue of its majority support, these decisions rest with the Executive Government. The Constitution also provides that the House of Representatives can continue for no longer than three years from the first meeting of the House.3 The significance of this to the concept of a representative Parliament and Government is that a Parliament is of limited duration on the democratic principle that the electors must be able to express their opinions at regular general elections. On the other hand a Parliament of short fixed-term duration may be viewed as undesirable in that too frequent elections have disruptive and/or negative effects on the parliamentary and governmental processes. Of further significance is the principle that Parliament should be neither out of existence nor out of action for any undue length of time. -

The Governance of Britain

The Governance of Britain Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Justice and Lord Chancellor by Command of Her Majesty July 2007 CM 7170 £13.50 © Crown Copyright 2007 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] Contents Foreword 5 Executive summary 6 Introduction 9 1. Limiting the powers of the executive 15 Moving royal prerogative powers to Parliament 16 Deploying the Armed Forces abroad 18 Ratifying treaties 19 Dissolving Parliament 20 Recalling the House of Commons 21 Placing the Civil Service on a statutory footing 21 Wider review and reforms of the prerogative executive powers 23 Role of the Attorney General 24 The Government’s role in ecclesiastical, judicial and public appointments 25 Appointments in the Church of England 25 Other non-executive appointments 27 Judicial appointments 27 Streamlining public appointments 28 Improving current processes and strengthening the House of Commons’ role 28 Limiting Ministers’ involvement in the granting of honours 30 2. Making the executive more accountable 31 National security 32 Intelligence and Security Committee 32 National Security Strategy 33 Parliament’s scrutiny of Government 34 Departmental debates in the House of Commons 34 Transparency of Government expenditure 35 Independence of the Office for National Statistics 36 Regions and responsibility 37 Regional Ministers 37 Regional select committees 38 Reforming the Ministerial Code 39 3. -

Constitutional Renewal Bill

Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty the Queen July 2009 Cm 7690 £9.50 0 Crown Copyright 2009 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 9780101769020 Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Contents Introduction 3 Protests 7 Attorney General and Prosecutions 14 Courts and Tribunals 20 Ratification of Treaties 30 The Civil Service 35 War Powers 46 Constitutional Renewal? 51 1 Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill 2 Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Introduction 1. The Government would like to thank the Joint Committee for their report on the Constitutional Renewal Bill. We are very grateful to the Committee for their thorough consideration of these complex and challenging issues. -

Procedures for Debates, Private Members' Bills and the Powers Of

House of Commons Procedure Committee Procedures for Debates, Private Members’ Bills and the Powers of the Speaker Fourth Report of Session 2002–03 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 19 November 2003 HC 333 Published on 27 November 2003 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £18.50 The Procedure Committee The Procedure Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider the practice and procedure of the House in the conduct of public business, and to make recommendations. Current membership Sir Nicholas Winterton MP (Conservative, Macclesfield) (Chairman) Mr Peter Atkinson MP (Conservative, Hexham) Mr John Burnett MP (Liberal Democrat, Torridge and West Devon) David Hamilton MP (Labour, Midlothian) Mr Eric Illsley MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Huw Irranca-Davies MP (Labour, Ogmore) Eric Joyce MP (Labour, Falkirk West) Mr Iain Luke MP (Labour, Dundee East) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Mr Tony McWalter MP (Labour, Hemel Hempstead) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Mr Desmond Swayne MP (Conservative, New Forest West) David Wright MP (Labour, Telford) Powers The powers of the committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 147. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_ committees/procedure_committee.cfm. -

Recall of Parliament

By Richard Kelly 16 September 2021 Recall of Parliament Summary 1 Recent recalls of the House of Commons 2 List of recalls 3 The procedure and calls for it to be changed 4 Members’ expenses associated with the recall of Parliament 5 Procedure in the House of Lords 6 Procedure in the Devolved Legislatures commonslibrary.parliament.uk Number 1186 Recall of Parliament Image Credits CRI-1564 by UK Parliament/Mark Crick image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped Disclaimer The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing ‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the conditions of the Open Parliament Licence. Feedback Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect subsequent changes. If you have any comments on our briefings please email [email protected]. Please note that authors are not always able to engage in discussions with members of the public who express opinions about the content of our research, although we will carefully consider and correct any factual errors. -

Constitution-Making and Reform

Constitution-making and Reform Options for the Process Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, and Anthony Regan Title Constitution-making and Reform: Options for the Process Authors Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, Anthony Regan Date September 2011 Publisher Interpeace ISBN 978-2-8399-0871-9 Printed in the USA Copyright © Interpeace 2011. All rights reserved. Reproduction of figures or short excerpts from this report is authorized free of charge and without formal written permission, provided that the original source is properly acknowledged, with mention of the complete name of the report, the publisher, and the numbering of the pages or figures. Permission can be granted only to use the material exactly as it is in the report. Figures may not be altered in any way, including the full legends. For media use it is sufficient to cite the source while using the original graphic or figure. This is an Interpeace publication. Interpeace’s publications do not reflect any specific national or political interest. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of Interpeace. For additional permissions or information please e-mail [email protected]. About Interpeace Interpeace has been enabling societies to build lasting peace since 1994. Interpeace is an independent, international peacebuilding organization and a strategic partner of the United Nations. It supports national teams in countries across Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe, and the Middle East. Interpeace also has a thematic program on constitution-making. Over 300 peacebuilding experts work to help their societies manage their internal divisions and conflicts without resorting to violence or coercion. -

Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill

HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Session 2007–08 Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Volume I: Report Ordered to be printed 22 July 2008 and published 31 July 2008 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords and the House of Commons London : The Stationery Office Limited £price HL Paper 166-I HC Paper 551-I Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill The Joint Committee was appointed to consider and report on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill published by the Ministry of Justice on 25 March 2008 (Cm 7342-II). The Committee was appointed by the House of Commons on 30 April 2008 and the House of Lords on 6 May 2008. Membership The Members of the Committee were: Lord Armstrong of Ilminster Mr Alistair Carmichael MP Lord Campbell of Alloway Christopher Chope MP Lord Fraser of Carmyllie Michael Jabez Foster MP (Chairman) Baroness Gibson of Market Rasen Mark Lazarowicz MP Lord Hart of Chilton Martin Linton MP Lord Maclennan of Rogart Ian Lucas MP Lord Morgan Fiona Mactaggart MP Lord Norton of Louth Mr Virendra Sharma MP Lord Plant of Highfield Emily Thornberry MP Lord Tyler Mr Andrew Tyrie MP Lord Williamson of Horton Sir George Young MP Full lists of Members’ interests are recorded in the Commons Register of Members’ Interests http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmregmem/memi02.htm and the Lords Register of Interests http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld/ldreg/reg01.htm Committee staff The staff of the Joint Committee were drawn from both Houses and comprised: -

Parliamentary Sovereignty and the Politics of Prorogation

Parliamentary Sovereignty and the Politics of Prorogation Richard Ekins Cover image: Prorogation marks the end of a parliamentary session. It is an announcement read by the Leader of the House of Lords, on behalf of the Queen, in the Lords chamber. It sets out major bills passed during the session and other measures taken by the government. MPs and House of Commons officials attend the Lords chamber to listen. Parliamentary copyright images are reproduced with the permission of Parliament. Photo Credit: Roger Harris Parliamentary Sovereignty and the Politics of Prorogation Richard Ekins Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. We are an independent, non-partisan educational charity whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas that will deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidence-based approach to policy development and retains copyright and full editorial control over all its written research. We work in partnership with academics and other experts and commission major studies involving thorough empirical research of alternative policy outcomes. We believe that the policy experience of other countries offers important lessons for government in the UK. We also believe that government has much to learn from business and the voluntary sector. Registered charity no: 1096300. Trustees Diana Berry, Alexander Downer, Pamela Dow, Andrew Feldman, Candida Gertler, Patricia Hodgson, Greta Jones, Edward Lee, Charlotte Metcalf, Roger Orf, Andrew Roberts, George Robinson, Robert Rosenkranz, Peter Wall, Nigel Wright. Parliamentary Sovereignty and the Politics of Prorogation About the Author Richard Ekins is Head of Policy Exchange’s Judicial Power Project. -

Taking Back Control: Why the House of Commons Should Govern

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE TAKING BACK CONTROL WHY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS SHOULD GOVERN ITS OWN TIME MEG RUSSELL AND DANIEL GOVER TAKING BACK CONTROL WHY THE HOUSE OF COMMONS SHOULD GOVERN ITS OWN TIME Meg Russell and Daniel Gover The Constitution Unit University College London January 2021 ISBN: 978-1-903903-90-2 Published by: The Constitution Unit School of Public Policy University College London 29-31 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU Tel: 020 7679 4977 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit ©The Constitution Unit, UCL 2021 This report is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. First Published January 2021 Front cover image by Vladimir Wrangel, cropped by the Constitution Unit. Contents List of boxes and tables ................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword by Sir David Natzler ....................................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................