The Table, Volume 86, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitution-Making and Reform: Options for the Process

Constitution-making and Reform Options for the Process Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, and Anthony Regan Title Constitution-making and Reform: Options for the Process Authors Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, Anthony Regan Date November 2011 Publisher Interpeace ISBN 978-2-8399-0871-9 Printed in Switzerland Copyright © Interpeace 2011. All rights reserved. Reproduction of figures or short excerpts from this report is authorized free of charge and without formal written permission, provided that the original source is properly acknowledged, with mention of the complete name of the report, the publisher, and the numbering of the pages or figures. Permission can be granted only to use the material exactly as it is in the report. Figures may not be altered in any way, including the full legends. For media use it is sufficient to cite the source while using the original graphic or figure. This is an Interpeace publication. Interpeace’s publications do not reflect any specific national or political interest. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of Interpeace. For additional permissions or information please e-mail [email protected]. About Interpeace Interpeace has been enabling societies to build lasting peace since 1994. Interpeace is an independent, international peacebuilding organization and a strategic partner of the United Nations. It supports national teams in countries across Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe, and the Middle East. Interpeace also has a thematic program on constitution-making. Over 300 peacebuilding experts work to help their societies manage their internal divisions and conflicts without resorting to violence or coercion. -

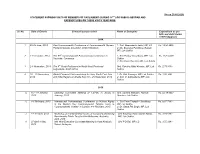

(As on 28.05.2020) STATEMENT SHOWING VISITS of MEMBERS of PARLIAMENT (DURING 16TH LOK SABHA) ABROAD and EXPENDITURES on THESE VISITS YEAR-WISE

(As on 28.05.2020) STATEMENT SHOWING VISITS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT (DURING 16TH LOK SABHA) ABROAD AND EXPENDITURES ON THESE VISITS YEAR-WISE Sl. No. Date of Events Events/Country visited Name of Delegates Expenditure as per bills and debit claims settled (Approx.) 2014 1 25-29 June, 2014 Pan-Commonwealth Conference of Commonwealth Women 1. Smt. Meenakashi Lekhi, MP, LS Rs. 14,90,882/- Parliamentarians in London, United Kingdom 2. Ms. Bhavana Pundikrao Gawali, MP, Lok Sabha 2 2-10 October, 2014 The 60th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference in 1. Shri Pankaj Choudhary, MP, Lok Rs. 16,81,447/- Yaounde, Cameroon Sabha 2. Shri Prem Das Rai, MP, Lok Sabha 3 2-8 November, 2014 The 6th Youth Parliament in North West Provincial Smt. Raksha Nikhil Khadse, MP, Lok Rs. 2,78,000/- Legislature, South Africa Sabha 4 18 – 20 November, Global Financial Crisis workshop for Asia, South East Asia 1. Dr. Kirit Somaiya, MP, Lok Sabha Rs. 1,58,369/- 2014 and India Regions in Dhaka from 18 – 20 November, 2014 2. Smt. V. Sathyabama MP, Lok Sabha 2015 5. 15 – 18 January, Standing Committee Meeting of CSPOC in Jersey in Smt. Sumitra Mahajan, Hon’ble Rs. 55,48,005/- 2015 January, 2015 Speaker, Lok Sabha 6. 4-6 February, 2015 International Parliamentary Conference on Human Rights 1. Shri Prem Prakash Chaudhary, Rs. 9,87,784/- in the Modern Day Commonwealth “Magna Carta to MP, Lok Sabha Commonwealth Charter” in London, 4-6 February, 2015 2. Dr. Satya Pal Singh, MP, Lok Sabha 7. 8 – 10 April, 2015 Workshop on Parliamentary Codes of Conduct-Establishing Shri Kinjarapu Ram Mohan Naidu, Rs. -

Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 15 October 2019 Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday, 15 October 2019 The PRESIDENT (The Hon. John George Ajaka) took the chair at 14:30. The PRESIDENT read the prayers and acknowledged the Gadigal clan of the Eora nation and its elders and thanked them for their custodianship of this land. Governor ADMINISTRATION OF THE GOVERNMENT The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of a message regarding the administration of the Government. Bills ABORTION LAW REFORM BILL 2019 Assent The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of message from the Governor notifying Her Excellency's assent to the bill. REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE REFORM BILL 2019 Protest The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of the following communication from the Official Secretary to the Governor of New South Wales: GOVERNMENT HOUSE SYDNEY Wednesday, 2 October, 2019 The Clerk of the Parliaments Dear Mr Blunt, I write at Her Excellency's command, to acknowledge receipt of the Protest made on 26 September 2019, under Standing Order 161 of the Legislative Council, against the Bill introduced as the "Reproductive Health Care Reform Bill 2019" that was amended so as to change the title to the "Abortion Law Reform Bill 2019'" by the following honourable members of the Legislative Council, namely: The Hon. Rodney Roberts, MLC The Hon. Mark Banasiak, MLC The Hon. Louis Amato, MLC The Hon. Courtney Houssos, MLC The Hon. Gregory Donnelly, MLC The Hon. Reverend Frederick Nile, MLC The Hon. Shaoquett Moselmane, MLC The Hon. Robert Borsak, MLC The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox, MLC The Hon. Mark Latham, MLC I advise that Her Excellency the Governor notes the protest by the honourable members. -

The Identification of Radicals in the British Parliament

1 HANSEN 0001 040227 名城論叢 2004年3月 31 THE IDENTIFICATION OF ‘RADICALS’ IN THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT, 1906-1914 P.HANSEN INTRODUCTION This article aims to identify the existence of a little known group of minority opinion in British society during the Edwardian Age. It is an attempt to define who the British Radicals were in the parliaments during the years immediately preceding the Great War. Though some were particularly interested in the foreign policy matters of the time,it must be borne in mind that most confined their energies to promoting the Liberal campaign for domestic welfare issues. Those considered or contemporaneously labelled as ‘Radicals’held ‘leftwing’views, being politically somewhat just left of centre. They were not revolutionaries or communists. They wanted change through reforms carried out in a democratic manner. Their failure to carry out changes on a significant scale was a major reason for the decline of the Liberals,and the rise and ultimate success of the Labour Party. Indeed, following the First World War, many Radicals defected from the Liberal Party to join Labour. With regard to historiography,it can be stated that the activities of British Radicals from the turn of the century to the outbreak of the First World War were the subject of interest to the most famous British historian of the second half of the 20century, A. J. P. Taylor. He wrote of them in his work The Troublemakers based on his Ford Lectures of 1956. By the early 1970s’A.J.A.Morris had established a reputation in the field with his book Radicalism Against War, 1906-1914 (1972),and a further publication of which he was editor,Edwardian Radical- ism 1900-1914 (1974). -

House of Commons Official Report Parliamentary Debates

Monday Volume 652 7 January 2019 No. 228 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 January 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

British Political System: PART II

1.Represents government 2.Symbol of authority and source of advice 3.Providing continuity and stability 4.Constitutional flexibility 5.Embodiment of tradition and object of identification for masses 6.Symbol of unity of the UK ▪ Hereditary head of state ▪ Part of both executive and legislative powers ▪ „the monarch reigns, but does not rule“ ▪ King can do no wrong (1711) 1.UK = parliamentary democracy + a constitutional sovereign as Head of State 2.Not publicly involved in the party politics of government 3.Entitled to be informed and consulted, and to advise, encourage and warn ministers 4.Royal Assent 5.Reserve power to dismiss the PM 6.Reserve power to make a personal choice of successor PM ▪ To appoint a Prime Minister of her [his] own choosing (1963) ▪ To dismiss a Prime Minister and his or her Government on the Monarch's own authority (1834) ▪ To summon and prorogue parliament ▪ To command the Armed Forces ▪ To dismiss and appoint Ministers ▪ To refuse the royal assent (1707/8) ▪ The power to declare War and Peace ▪ The power to deploy the Armed Forces overseas ▪ The power to ratify and make treaties ▪ But 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act ▪ codifying the Ponsonby Rule (constitutional convention: most international treaties had to be laid before Parliamet 21 days before ratification ▪ Personal, political and criminal inviolability ▪ Unaccountability ▪ To issue and withdraw passports ▪ To appoint Bishops and Archbishops of the Church of England ▪ To grant honours ▪ Prerogative of Mercy ▪ …. ▪ Annually ▪ Tradition from 1600s ▪ Current ceremony 1852 ▪ Presented in HL ▪ HC members present too ▪ Followed by ▪ 'Humble Address to the Queen ▪ Parliamentary debate on the Speech ▪ 4-5 days ▪ Speech is then approved of by HC ▪ Above-parties ▪ No participation in elections ▪ Co-operate with any cabinet ▪ Avoid controversial statements ▪ „King can do no wrong“, if his steps consulted with the cabinet ▪ Part of the parliament ▪ Royal Assent (no legislative initiative) ▪ Bagehot (1867): „But the Queen has no such veto. -

Tempered Radicals and Servant Leaders: Portraits of Spirited Leadership Amongst African Women Leaders

TEMPERED RADICALS AND SERVANT LEADERS: PORTRAITS OF SPIRITED LEADERSHIP AMONGST AFRICAN WOMEN LEADERS Faith Wambura Ngunjiri A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2006 Committee: Judy A. Alston, Advisor Laura B. Lengel Graduate Faculty Representative Mark A. Earley Khaula Murtadha © 2006 Faith Wambura Ngunjiri All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Judy A. Alston, Advisor There have been few studies on experiences of African women in leadership. In this study, I aimed at contributing to bridging that literature gap by adding the voices of African women leaders who live and work in or near Nairobi Kenya in East Africa. The purpose of this study was to explore, explain and seek to understand women’s leadership through the lived experiences of sixteen women leaders from Africa. The study was an exploration of how these women leaders navigated the intersecting oppressive forces emanating from gender, culture, religion, social norm stereotypes, race, marital status and age as they attempted to lead for social justice. The central biographical methodology utilized for this study was portraiture, with the express aim of celebrating and learning from the resiliency and strength of the women leaders in the face of adversities and challenges to their authority as leaders. Leadership is influence and a process of meaning making amongst people to engender commitment to common goals, expressed in a community of practice. I presented short herstories of eleven of the women leaders, and in depth portraits of the other five who best illustrated and expanded the a priori conceptual framework. -

Translating the Constitution Act, 1867

TRANSLATING THE CONSTITUTION ACT, 1867 A Legal-Historical Perspective by HUGO YVON DENIS CHOQUETTE A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Law in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 2009 Copyright © Hugo Yvon Denis Choquette, 2009 Abstract Twenty-seven years after the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982, the Constitution of Canada is still not officially bilingual in its entirety. A new translation of the unilingual Eng- lish texts was presented to the federal government by the Minister of Justice nearly twenty years ago, in 1990. These new French versions are the fruits of the labour of the French Constitutional Drafting Committee, which had been entrusted by the Minister with the translation of the texts listed in the Schedule to the Constitution Act, 1982 which are official in English only. These versions were never formally adopted. Among these new translations is that of the founding text of the Canadian federation, the Constitution Act, 1867. A look at this translation shows that the Committee chose to de- part from the textual tradition represented by the previous French versions of this text. In- deed, the Committee largely privileged the drafting of a text with a modern, clear, and con- cise style over faithfulness to the previous translations or even to the source text. This translation choice has important consequences. The text produced by the Commit- tee is open to two criticisms which a greater respect for the prior versions could have avoided. First, the new French text cannot claim the historical legitimacy of the English text, given their all-too-dissimilar origins. -

Proposed Redistribution of Victoria Into Electoral Divisions: April 2017

Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions APRIL 2018 Report of the Redistribution Committee for Victoria Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management and Community Engagement Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in other languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-58-9 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 © Victoria 2018 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for Victoria, Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions. 18_0990 The Redistribution Committee for Victoria (the Redistribution Committee) has undertaken a proposed redistribution of Victoria. In developing the redistribution proposal, the Redistribution Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed electoral divisions meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The Redistribution Committee commends its redistribution -

House of Commons Thursday 12 July 2012 Votes and Proceedings

No. 31 251 House of Commons Thursday 12 July 2012 Votes and Proceedings The House met at 10.30 am. PRAYERS. 1 Questions to the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change 2 Urgent Question: Olympics security (Secretary Theresa May) 3 Statements: (1) Balance of competences (Secretary William Hague) (2) Business (Leader of the House) 4 Court of Justice of the European Union Resolved, That this House takes note of the draft Regulation 2011/0901A(COD) of the European Parliament and of the Council (amending the Protocol on the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union and Annex 1 thereto) and draft Regulation 2011/0902(COD) (relating to temporary Judges of the European Union Civil Service Tribunal) and, in accordance with section 10 of the European Union Act 2011, approves Her Majesty’s Government’s intention to support the adoption of draft Regulations 2011/0901A(COD) and 2011/0902(COD) of the European Parliament and of the Council.—(Mr David Lidington.) 5 Preparation of the 2013 European Union Budget Motion made and Question proposed, That this House takes note of an unnumbered Explanatory Memorandum dated 5 June 2012 from HM Treasury on the Statement of Estimates of the Commission for 2013 (Preparation of the 2013 Draft Budget); recalls the agreement at the October 2010 European Council and the Prime Minister’s letter of 18 December 2010 to European Commission President Manuel Barroso, which both note that it is essential that the European Union budget and the forthcoming Multi-Annual Financial Framework reflect the consolidation -

2019 Nsw State Budget Estimates – Relevant Committee Members

2019 NSW STATE BUDGET ESTIMATES – RELEVANT COMMITTEE MEMBERS There are seven “portfolio” committees who run the budget estimate questioning process. These committees correspond to various specific Ministries and portfolio areas, so there may be a range of Ministers, Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries and senior public servants from several Departments and Authorities who will appear before each committee. The different parties divide up responsibility for portfolio areas in different ways, so some minor party MPs sit on several committees, and the major parties may have MPs with titles that don’t correspond exactly. We have omitted the names of the Liberal and National members of these committees, as the Alliance is seeking to work with the Opposition and cross bench (non-government) MPs for Budget Estimates. Government MPs are less likely to ask questions that have embarrassing answers. Victor Dominello [Lib, Ryde], Minister for Customer Services (!) is the minister responsible for Liquor and Gaming. Kevin Anderson [Nat, Tamworth], Minister for Better Regulation, which is located in the super- ministry group of Customer Services, is responsible for Racing. Sophie Cotsis [ALP, Canterbury] is the Shadow for Better Public Services, including Gambling, Julia Finn [ALP, Granville] is the Shadow for Consumer Protection including Racing (!). Portfolio Committee no. 6 is the relevant committee. Additional information is listed beside each MP. Bear in mind, depending on the sitting timetable (committees will be working in parallel), some MPs will substitute in for each other – an MP who is not on the standing committee but who may have a great deal of knowledge might take over questioning for a session. -

Constitution Constitution of Canada Du Canada

SENATE SÉNAT HOUSE OF COMMONS CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES Issue No.9 Fascicule n.9 Thursday, November 20, 1980 Le jeudi 20 novembre 1980 Joint Chairmen: Coprésidents: Sen¡tor Harry Hays Sénateur Harry Hays Serge Joyal, M.P. Serge Joyal, député Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence P rocès - ve rbaux et t émoi gnages of the Special Joint Committee of du Comité mixte spécial the Senate and of du Sénat et de the House of Commons on the la Chambre des communes sur la Constitution Constitution of Canada du Canada RESPECTING: CONCERNANT: The document entitled "Proposed Resolution for a Le document intitulé <Projet de résolution portant Joint Address to Her Majesty the eueen adresse commune à Sa Majesté la Reine respecting the Constitution of Canada" published concernant la Constitution du Canadar, publié par by the Government on October 2,1980 le gouvernement le 2 octobre 1980 iforme edela WITNESSES: TEMOINS: (See back cover) (Voir à l'endos) First Session of the Première session de la Thirty-second Parliament, 1 980 trente-deuxième législature, I 980 I 0s9 SPECIAL JOINT COMMITTEE OF COMITÉ MIXTE SPÉCIAL DU SÉNAT THE SENATE AND OF THE HOUSE ET DE LA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES OF COMMONS ON THE CONSTITUTION SUR LA CONSTITUTION DU CANADA OF CANADA Joint Chairmen; Coprésidents: Senator'Harry Hays Sénateur Harry Hays Serge Joyal, M.P. Serge Joyal, député Re pres e nt i ng t he S e nat e: Représentant le Sénat: Senators: Les sénateurs: Austin Haidasz Muir Rousseau Bielish Lapointe Nieman Tremblay-( l0) Bird Representing the House of Commons: Représentant la Chambre des communes: Messrs.