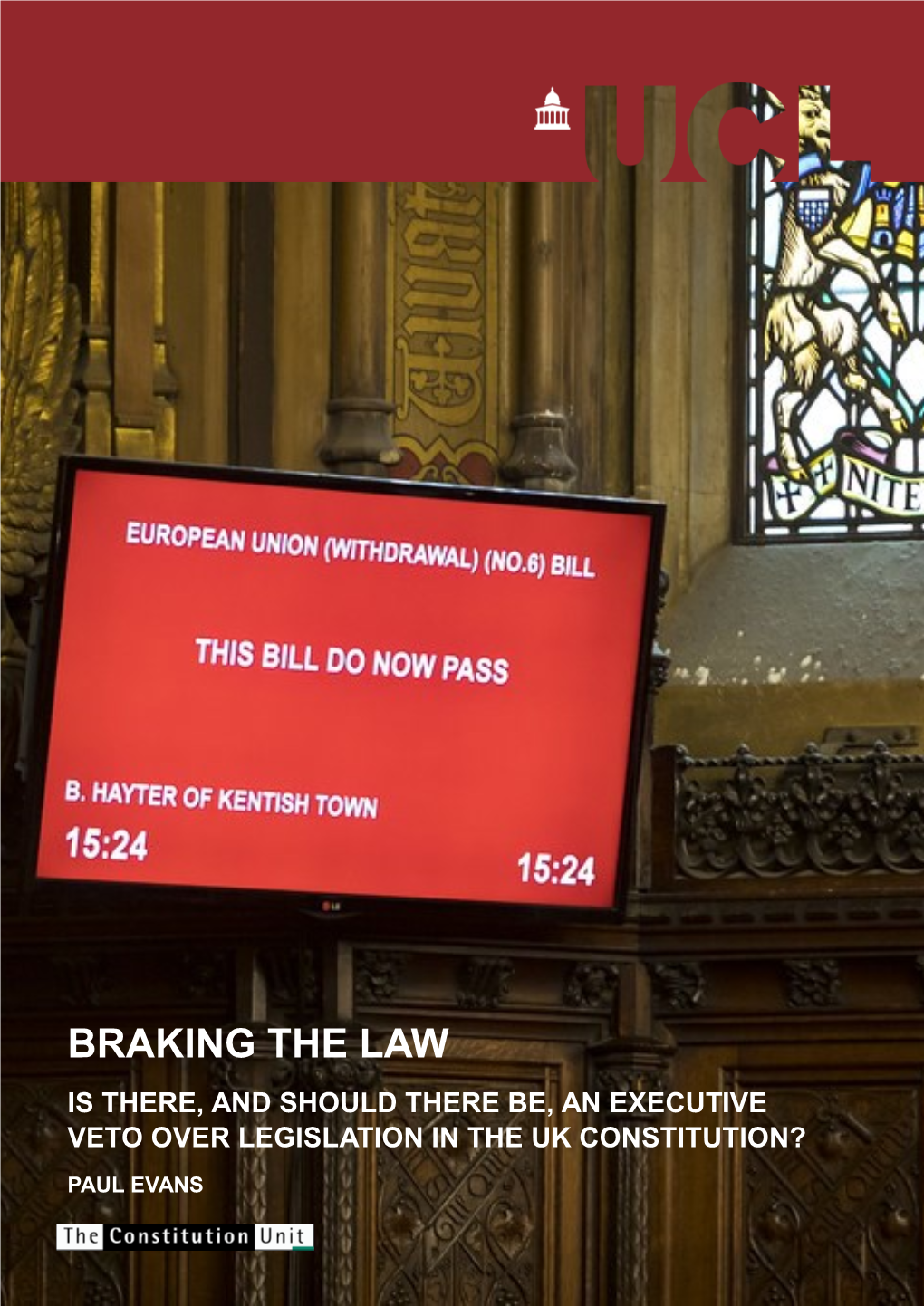

Braking the Law: Is There, and Should There Be, an Executive Veto Over

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF on Financial Privilege

Report Financial Privilege The Undoubted and Sole Right of the Commons? Sir Malcolm Jack KCB PhD FSA Richard Reid PhD FINANCIAL PRIVILEGE THE UNDOUBTED AND SOLE RIGHT OF THE COMMONS? By Sir Malcolm Jack KCB PhD FSA and Richard Reid PhD Acknowlegements The authors thank The Constitution Society for commissioning and publishing this paper. First published in Great Britain in 2016 by The Constitution Society Top Floor, 61 Petty France London SW1H 9EU www.consoc.org.uk © The Constitution Society ISBN: 978-0-9954703-0-9 © Malcolm Jack and Richard Reid 2016. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. FINANCIAL PRIVILEGE 3 Contents Acknowlegements 2 About the Authors 4 Summary 5 PART 1 Conventions in Respect of Financial Privilege 6 PART 2 Parliament Acts 19 PART 3 Handling of Bills with Financial Provisions 30 PART 4 Secondary Legislation 41 PART 5 The Strathclyde Review 51 Appendix 1 Parliament Act 1911 62 Appendix 2 Parliament Act 1949 67 4 FINANCIAL PRIVILEGE About the Authors Sir Malcolm Jack was Clerk of the House of Commons from 2006–2011. He is editor of the current, twenty-fourth edition of Erskine May’s Parliamentary Practice, 2011. He lectures and writes on constitutional and historical subjects, having published widely on the history of ideas as well as on aspects of British, European and South African history. -

Constitution-Making and Reform: Options for the Process

Constitution-making and Reform Options for the Process Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, and Anthony Regan Title Constitution-making and Reform: Options for the Process Authors Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, Anthony Regan Date November 2011 Publisher Interpeace ISBN 978-2-8399-0871-9 Printed in Switzerland Copyright © Interpeace 2011. All rights reserved. Reproduction of figures or short excerpts from this report is authorized free of charge and without formal written permission, provided that the original source is properly acknowledged, with mention of the complete name of the report, the publisher, and the numbering of the pages or figures. Permission can be granted only to use the material exactly as it is in the report. Figures may not be altered in any way, including the full legends. For media use it is sufficient to cite the source while using the original graphic or figure. This is an Interpeace publication. Interpeace’s publications do not reflect any specific national or political interest. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of Interpeace. For additional permissions or information please e-mail [email protected]. About Interpeace Interpeace has been enabling societies to build lasting peace since 1994. Interpeace is an independent, international peacebuilding organization and a strategic partner of the United Nations. It supports national teams in countries across Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe, and the Middle East. Interpeace also has a thematic program on constitution-making. Over 300 peacebuilding experts work to help their societies manage their internal divisions and conflicts without resorting to violence or coercion. -

President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

I McN A I R PAPERS NUMBER THREE PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL S~RATEGIC STUDIES I~j~l~ ~p~ 1~ ~ ~r~J~r~l~j~E~J~p~j~r~lI~1~1~L~J~~~I~I~r~ ~'l ' ~ • ~i~i ~ ,, ~ ~!~ ,,~ i~ ~ ~~ ~~ • ~ I~ ~ ~ ~i! ~H~I~II ~ ~i~ ,~ ~II~b ~ii~!i ~k~ili~Ii• i~i~II~! I ~I~I I• I~ii kl .i-I k~l ~I~ ~iI~~f ~ ~ i~I II ~ ~I ~ii~I~II ~!~•b ~ I~ ~i' iI kri ~! I ~ • r rl If r • ~I • ILL~ ~ r I ~ ~ ~Iirr~11 ¸I~' I • I i I ~ ~ ~,i~i~I•~ ~r~!i~il ~Ip ~! ~ili!~Ii!~ ~i ~I ~iI•• ~ ~ ~i ~I ~•i~,~I~I Ill~EI~ ~ • ~I ~I~ I¸ ~p ~~ ~I~i~ PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH.'? PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW I Introduction N THE MAKING and conduct of foreign policy, ~ Congress and the President have been rivalrous part- ners for two hundred years. It is not hyperbole to call the current round of that relationship a crisis--the most serious constitutional crisis since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Roosevelt's court-packing initiative was highly visible and the reaction to it violent and widespread. It came to an abrupt and dramatic end, some said as the result of Divine intervention, when Senator Joseph T. Robinson, the Senate Majority leader, dropped dead on the floor of the Senate while defending the President's bill. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

11-01-2021 These Matters Were Called on for Hearing Today

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA INHERENT JURISDICTION REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO.¼¼¼¼¼/2021 (Diary No. 45777/2018) IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 494 OF 2012 Beghar Foundation through its Secretary and Anr. Petitioner(s) versus Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) and Ors. Respondent(s) with REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 3948 OF 2018 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 231 OF 2016 Jairam Ramesh Petitioner(s) versus Union of India and Ors. Respondent(s) with REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 22 OF 2019 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 1014 OF 2017 1 M.G. Devasahayam Petitioner(s) versus Union of India and Anr. Respondent(s) with REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 31 OF 2019 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 1058 OF 2017 Mathew Thomas Petitioner(s) versus Union of India and Ors. Respondent(s) with REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO.¼¼¼¼¼/2021 (Diary No. 48326/2018) IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 494 OF 2012 Imtiyaz Ali Palsaniya Petitioner(s) versus Union of India and Ors. Respondent(s) with REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 377 OF 2019 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 342 OF 2017 2 Shantha Sinha and Anr. Petitioner(s) versus Union of India and Anr. Respondent(s) with REVIEW PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 924 OF 2019 IN WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 829 OF 2013 S.G. Vombatkere and Anr. Petitioner(s) versus Union of India and Ors. Respondent(s) O R D E R Permission to file Review Petition(s) is granted. Delay condoned. Prayer for open Court/personal hearing of Review Petition(s) is rejected. The present review petitions have been filed against the final judgment and order dated 26.09.2018. -

Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship Sarah Miskin Politics and Public Administration Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Martin Lumb and Janet Wilson for their help with the research into party defections in Australia and Cathy Madden, Scott Bennett, David Farrell and Ben Miskin for reading and commenting on early drafts. -

Appropriations for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2019, and for Other Purposes

H. J. Res. 31 One Hundred Sixteenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE FIRST SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Thursday, the third day of January, two thousand and nineteen Joint Resolution Making consolidated appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2019, and for other purposes. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019’’. SEC. 2. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Sec. 1. Short title. Sec. 2. Table of contents. Sec. 3. References. Sec. 4. Statement of appropriations. Sec. 5. Availability of funds. Sec. 6. Adjustments to compensation. Sec. 7. Technical correction. DIVISION A—DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 2019 Title I—Departmental Management, Operations, Intelligence, and Oversight Title II—Security, Enforcement, and Investigations Title III—Protection, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Title IV—Research, Development, Training, and Services Title V—General Provisions DIVISION B—AGRICULTURE, RURAL DEVELOPMENT, FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 2019 Title I—Agricultural Programs Title II—Farm Production and Conservation Programs Title III—Rural Development Programs Title IV—Domestic Food Programs Title V—Foreign Assistance and Related Programs Title VI—Related Agency and Food and Drug Administration Title VII—General Provisions DIVISION C—COMMERCE, JUSTICE, SCIENCE, AND RELATED AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 2019 Title I—Department of Commerce Title II—Department of Justice Title III—Science Title IV—Related Agencies Title V—General Provisions DIVISION D—FINANCIAL SERVICES AND GENERAL GOVERNMENT APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 2019 Title I—Department of the Treasury Title II—Executive Office of the President and Funds Appropriated to the President Title III—The Judiciary Title IV—District of Columbia H. -

The Estimates of Appropriations 2021/22 - Justice Sector B.5 Vol.7 | I

B.5 Vol.7 The Estimates of Appropriations for the Government of New Zealand for the Year Ending 30 June 2022 Justice Sector 20 May 2021 ISBN: 978-1-99-004520-2 (print) 978-1-99-004521-9 (online) Guide to the Budget Documents A number of documents are released on Budget day. The purpose of these documents is to provide information about the Government’s fiscal intentions for the year ahead and the wider fiscal and economic picture. The documents released on Budget day are as follows: Budget at a Glance The Budget at a Glance is an overview of the Budget information and contains the main points for the media and public. This summarises the Government’s spending decisions and key points raised in the Budget Speech, the Wellbeing Budget 2021, and the Budget Economic and Fiscal Update. Wellbeing Budget 2021 The Wellbeing Budget 2021 is the main source of Budget information. It sets out the Government’s priorities for the Budget, the approach taken to develop it, and a summary of all initiatives included in Budget 2021. It also contains reports on fiscal strategy and child poverty, as required by the Public Finance Act 1989. These outline respectively the Government’s short-term fiscal intentions and long-term fiscal objectives, and how the Government is progressing towards its child poverty targets. The Summary of Budget Initiatives document is included as an annex. Budget Speech The Budget Speech is the Budget Statement the Minister of Finance delivers at the start of Parliament's Budget debate. The Budget Statement generally focuses on the overall fiscal and economic position, the Government’s policy priorities and how those priorities will be funded. -

Beyond Accountability Lisa Schultz Bressman

Vanderbilt University Law School Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2003 Beyond Accountability Lisa Schultz Bressman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Agency Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa Schultz Bressman, Beyond Accountability, 78 Beyond Accountability. 461 (2003) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/884 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES BEYOND ACCOUNTABILITY: ARBITRARINESS AND LEGITIMACY IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE STATE LISA SCHULTZ BRESSMAN* This Article argues that efforts to square the administrative state with the constitu- tional structure have become too fixated on the concern for political accountability. As a result, those efforts have overlooked an important obstacle to agency legiti- macy: the concern for administrative arbitrariness. Such thinking is evident in the prevailing model of the administrative state, which seeks to legitimate agencies by placing their policy decisions firmly under the control of the one elected official responsive to the entire nation-the President. This Article contends that the "pres- idential control" model cannot legitimate agencies because the model rests on a mistaken assumption about the sufficiency of political accountability for that pur- pose. The assumption resonates with the premise, familiar in constitutional theory, that majoritarianism is the hallmark of legitimate government. -

The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/82h2630k Journal Parliamentary Affairs, 61 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM By Mark Bevir Published in: Parliamentary Affairs 61 (2008), 559-577. I. CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1950 Email: [email protected] II. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Mark Bevir is a Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of The Logic of the History of Ideas (1999) and New Labour: A Critique (2005), and co-author, with R. A. W. Rhodes, of Interpreting British Governance (2003) and Governance Stories (2006). 1 Abstract How are we to interpret judicial reform under New Labour? What are its implications for democracy? This paper argues that the reforms are part of a broader process of juridification. The Westminster Model, as derived from Dicey, upheld a concept of parliamentary sovereignty that gives a misleading account of the role of the judiciary. Juridification has arisen along with new theories and new worlds of governance that both highlight and intensify the limitations of the Westminster Model so conceived. New Labour’s judicial reforms are attempts to address problems associated with the new governance. Ironically, however, the reforms are themselves constrained by a lingering commitment to an increasingly out-dated Westminster Model. 2 THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM Immediately following the 1997 general election in Britain, the New Labour government started to pursue a series of radical constitutional reforms with the overt intention of making British political institutions more effective and more accountable. -

Legislative Process Lpbooklet 2016 15Th Edition.Qxp Booklet00-01 12Th Edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1

LPBkltCvr_2016_15th edition-1.qxp_BkltCvr00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 2:49 PM Page 1 South Carolina’s Legislative Process LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 2 October 2016 15th Edition LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 3 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS The contents of this pamphlet consist of South Carolina’s Legislative Process , pub - lished by Charles F. Reid, Clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. The material is reproduced with permission. LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 4 LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 5 South Carolina’s Legislative Process HISTORY o understand the legislative process, it is nec - Tessary to know a few facts about the lawmak - ing body. The South Carolina Legislature consists of two bodies—the Senate and the House of Rep - resentatives. There are 170 members—46 Sena - tors and 124 Representatives representing dis tricts based on population. When these two bodies are referred to collectively, the Senate and House are together called the General Assembly. To be eligible to be a Representative, a person must be at least 21 years old, and Senators must be at least 25 years old. Members of the House serve for two years; Senators serve for four years. The terms of office begin on the Monday following the General Election which is held in even num - bered years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. -

Part 2 Chapter 3 Such Privileges As Were Imported by the A…

Chapter 3 Such privileges as were imported by the adoption of the Bill of Rights 3.1 Statutory recognition of the freedom of speech for members of the Parliament of New South Wales The most fundamental parliamentary privilege is the privilege of freedom of speech. In Australia, there is no restriction on what may be said by elected representatives speaking in Parliament. Freedom of political speech is considered essential in order to ensure that the Parliament can carry out its role of scrutinising the operation of the government of the day, and inquiring into matters of public concern. The statutory recognition of this privilege is founded in the Bill of Rights 1688 . Article 9 provides: The freedome of speech and debates or proceedings in Parlyament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parlyament. Apart from the absolute protection afforded to statements made in Parliament, other privileges which flow from the Bill of Rights include: the right to exclude strangers or visitors; the right to control publication of debates and proceedings; and the protection of witnesses etc. before the Parliament and its committees. 1 Article 9 is in force in New South Wales by operation of the Imperial Acts Application Act 1969.2 Members are protected under this Act from prosecution for anything said during debate in the House or its committees. Despite this, in 1980 Justice McLelland expressed doubts about the applicability of Article 9 to the New South Wales Parliament in Namoi Shire Council v Attorney General. He stated that “art 9 of the Bill of Rights does not purport to apply to any legislature other than the Parliament at Westminster” and therefore, the supposed application of the article, does not extend to the Legislature of New South Wales.