President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALBERTA SECURITIES COMMISSION DECISION Citation

ALBERTA SECURITIES COMMISSION DECISION Citation: Re Global 8 Environmental Technologies, Inc., 2015 ABASC 734 Date: 20150605 Global 8 Environmental Technologies, Inc., Halo Property Services Inc., Canadian Alternative Resources Inc., Milverton Capital Corporation, Rene Joseph Branconnier and Chad Delbert Burback Panel: Kenneth Potter, QC Fred Snell, FCA Appearing: Robert Stack, Liam Oddie and Heather Currie for Commission Staff H. Roderick Anderson for René Joseph Branconnier Patricia Taylor for Chad Delbert Burback Daniel Wolf for Global 8 Environmental Technologies, Inc. Submissions Completed: 26 November 2014 Decision: 5 June 2015 5176439.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................... 1 A. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1. G8 .................................................................................................................1 2. Halo and CAR ..............................................................................................2 B. History of the Proceedings ...................................................................................... 2 C. Certain Prior Orders ................................................................................................ 3 D. Summary of Conclusion ......................................................................................... 3 II. PROCEDURAL AND EVIDENTIARY MATTERS -

Empire and English Nationalismn

Nations and Nationalism 12 (1), 2006, 1–13. r ASEN 2006 Empire and English nationalismn KRISHAN KUMAR Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, USA Empire and nation: foes or friends? It is more than pious tribute to the great scholar whom we commemorate today that makes me begin with Ernest Gellner. For Gellner’s influential thinking on nationalism, and specifically of its modernity, is central to the question I wish to consider, the relation between nation and empire, and between imperial and national identity. For Gellner, as for many other commentators, nation and empire were and are antithetical. The great empires of the past belonged to the species of the ‘agro-literate’ society, whose central fact is that ‘almost everything in it militates against the definition of political units in terms of cultural bound- aries’ (Gellner 1983: 11; see also Gellner 1998: 14–24). Power and culture go their separate ways. The political form of empire encloses a vastly differ- entiated and internally hierarchical society in which the cosmopolitan culture of the rulers differs sharply from the myriad local cultures of the subordinate strata. Modern empires, such as the Soviet empire, continue this pattern of disjuncture between the dominant culture of the elites and the national or ethnic cultures of the constituent parts. Nationalism, argues Gellner, closes the gap. It insists that the only legitimate political unit is one in which rulers and ruled share the same culture. Its ideal is one state, one culture. Or, to put it another way, its ideal is the national or the ‘nation-state’, since it conceives of the nation essentially in terms of a shared culture linking all members. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Beyond Accountability Lisa Schultz Bressman

Vanderbilt University Law School Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2003 Beyond Accountability Lisa Schultz Bressman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Agency Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa Schultz Bressman, Beyond Accountability, 78 Beyond Accountability. 461 (2003) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/884 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES BEYOND ACCOUNTABILITY: ARBITRARINESS AND LEGITIMACY IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE STATE LISA SCHULTZ BRESSMAN* This Article argues that efforts to square the administrative state with the constitu- tional structure have become too fixated on the concern for political accountability. As a result, those efforts have overlooked an important obstacle to agency legiti- macy: the concern for administrative arbitrariness. Such thinking is evident in the prevailing model of the administrative state, which seeks to legitimate agencies by placing their policy decisions firmly under the control of the one elected official responsive to the entire nation-the President. This Article contends that the "pres- idential control" model cannot legitimate agencies because the model rests on a mistaken assumption about the sufficiency of political accountability for that pur- pose. The assumption resonates with the premise, familiar in constitutional theory, that majoritarianism is the hallmark of legitimate government. -

The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/82h2630k Journal Parliamentary Affairs, 61 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM By Mark Bevir Published in: Parliamentary Affairs 61 (2008), 559-577. I. CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1950 Email: [email protected] II. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Mark Bevir is a Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of The Logic of the History of Ideas (1999) and New Labour: A Critique (2005), and co-author, with R. A. W. Rhodes, of Interpreting British Governance (2003) and Governance Stories (2006). 1 Abstract How are we to interpret judicial reform under New Labour? What are its implications for democracy? This paper argues that the reforms are part of a broader process of juridification. The Westminster Model, as derived from Dicey, upheld a concept of parliamentary sovereignty that gives a misleading account of the role of the judiciary. Juridification has arisen along with new theories and new worlds of governance that both highlight and intensify the limitations of the Westminster Model so conceived. New Labour’s judicial reforms are attempts to address problems associated with the new governance. Ironically, however, the reforms are themselves constrained by a lingering commitment to an increasingly out-dated Westminster Model. 2 THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM Immediately following the 1997 general election in Britain, the New Labour government started to pursue a series of radical constitutional reforms with the overt intention of making British political institutions more effective and more accountable. -

Legislative Process Lpbooklet 2016 15Th Edition.Qxp Booklet00-01 12Th Edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1

LPBkltCvr_2016_15th edition-1.qxp_BkltCvr00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 2:49 PM Page 1 South Carolina’s Legislative Process LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 2 October 2016 15th Edition LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 3 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS The contents of this pamphlet consist of South Carolina’s Legislative Process , pub - lished by Charles F. Reid, Clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. The material is reproduced with permission. LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 4 LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 5 South Carolina’s Legislative Process HISTORY o understand the legislative process, it is nec - Tessary to know a few facts about the lawmak - ing body. The South Carolina Legislature consists of two bodies—the Senate and the House of Rep - resentatives. There are 170 members—46 Sena - tors and 124 Representatives representing dis tricts based on population. When these two bodies are referred to collectively, the Senate and House are together called the General Assembly. To be eligible to be a Representative, a person must be at least 21 years old, and Senators must be at least 25 years old. Members of the House serve for two years; Senators serve for four years. The terms of office begin on the Monday following the General Election which is held in even num - bered years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

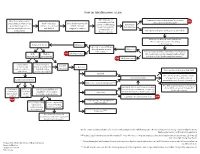

Idea Becomes a Law

How an Idea Becomes a Law Bill is introduced Ideas from many sources: Committee reports “do not pass” or does not STOP and undergoes First constituents, interest groups, Author requests Bill is filed electronically take action on the measure.* and Second Readings. Committee government agencies, bill to be researched with Clerk and is Speaker assigns it to Consideration interim studies, businesses, and drafted. assigned a number. committee(s) or the Governor. Bill reported “do pass” or “do pass as amended.” direct to calendar. Bill moves to General Order. Available to Floor Leader for possible scheduling Returned to House Bill passes on Floor Agenda. Engrossed to Senate: Bill goes through similar process Bill passes in the Senate. ** Floor Consideration: Bill scheduled on Floor Agenda. With Without STOP Bill does not pass Bill is explained, possibly amended, debated, and amendments amendments voted upon. Third Reading and final passage. ** STOP Bill does not pass House refuses House concurs in Enrolled to concur and Senate amendments. To Governor to Governor requests conference Fourth Reading Becomes law on date specified in bill with Senate. and final passage.** Signs bill If no date is specified, and bill contains To Secretary of State emergency clause, bill is effective Conference Committee immediately upon Governor’s signature. Bill becomes law without signature*** If no date is specified, and no emergency Two-thirds vote in each house to override clause, bill becomes law 90 days after Conference CCR filed: CCR electronically filed and veto, unless passed with an emergency, sine die adjournment. Committee Conferees available for Floor Leader Vetoes bill which then requires a three-fourths vote. -

Australia's Political System

Australia’s Political System Australia's Political System Australia's system of government is based on the liberal democratic tradition, which includes religious tolerance and freedom of speech and association. It's institutions and practices reflect British and North American models but are uniquely Australian. The Commonwealth of Australia was created on January 1, 1901 - Federation Day - when six former British colonies - now the six States of Australia - agreed to form a union. The Australian Constitution, which took effect on January 1, 1901, lays down the framework for the Australian system of government. The Constitution The Australian Constitution sets out the rules and responsibilities of government and outlines the powers of its three branches - legislative, executive and judicial. The legislative branch of government contains the parliament - the body with the legislative power to make laws. The executive branch of government administers the laws made by the legislative branch, and the judicial branch of government allows for the establishment of the country's courts of law and the appointment and removal of it judges. The purpose of the courts is to interpret all laws, including the Constitution, making the rule of law supreme. The Constitution can only be changed by referendum. Australia's Constitutional Monarchy Australia is known as a constitutional monarchy. This means it is a country that has a queen or king as its head of state whose powers are limited by a Constitution. Australia's head of state is Queen Elizabeth II. Although she is also Queen of the United Kingdom, the two positions now are quite separate, both in law and constitutional practice. -

Mayors' Monarch Pledge

Mayors’ Monarch Pledge Action Items Mayors and local government chief executives who have taken the Mayors’ Monarch Pledge must commit to implement at least three of the 25 following action items within a year of taking the pledge. At least one action must be taken from the “Program & Demonstration Gardens” section. Mayors and local government chief executives taking more than eight actions will receive special recognition as part of the National Wildlife Federation’s Mayors’ Monarch Leadership Circle. NWF will follow up with all mayoral points of contact with a quarterly survey (1/1, 4/1, 7/1, 10/1) to monitor progress. Please visit www.nwf.org/mayorsmonarchpledge to take the pledge and access resources. Communications & Convening: 1) Issue a Proclamation to raise awareness about the decline of the monarch butterfly and the species’ need for habitat. 2) Launch a public communication effort to encourage citizens to plant monarch gardens at their homes or in their neighborhoods. 3) Communicate with community garden groups and urge them to plant native milkweeds and nectar-producing plants. 4) Convene city park and public works department staff and identify opportunities for revised mowing programs and milkweed / native nectar plant planting programs. 5) Convene a meeting with gardening leaders in the community to discuss partnerships to support monarch butterfly conservation. Program & Demonstration Gardens: 6) Host or support a native plant sale or milkweed seed giveaway event. 7) Facilitate or support a milkweed seed collection and propagation effort. 8) Plant a monarch-friendly demonstration garden at City Hall or another prominent location. 9) Convert abandoned lots to monarch habitat. -

Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019

16 March — 14 July 2019 British Royal Portraits Exhibition organised by the National Portrait Gallery, London Contextual Information Timelines and Family Trees Tudors to Windsors: British Royal Portraits 16 March – 14 July 2019 Tudors to Windsors traces the history of the British monarchy through the outstanding collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. This exhibition highlights major events in British (and world) history from the sixteenth century to the present, examining the ways in which royal portraits were impacted by both the personalities of individual monarchs and wider historical change. Presenting some of the most significant royal portraits, the exhibition will explore five royal dynasties: the Tudors, the Stuarts, the Georgians, the Victorians and the Windsors shedding light on key figures and important historical moments. This exhibition also offers insight into the development of British art including works by the most important artists to have worked in Britain, from Sir Peter Lely and Sir Godfrey Kneller to Cecil Beaton and Annie Leibovitz. 2 UK WORLDWIDE 1485 Henry Tudor defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field, becoming King Henry VII The Tudors and founding the Tudor dynasty 1492 An expedition led by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus encounters the Americas 1509 while searching for a Western passage to Asia Henry VII dies and is succeeded Introduction by King Henry VIII 1510 The Inca abandon the settlement of Machu Picchu in modern day Peru Between 1485 and 1603, England was ruled by 1517 Martin Luther nails his 95 theses to the five Tudor monarchs. From King Henry VII who won the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, crown in battle, to King Henry VIII with his six wives and a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation 1519 Elizabeth I, England’s ‘Virgin Queen’, the Tudors are some Hernando Cortes lands on of the most familiar figures in British history. -

Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/02/2021 09:03:16PM Via Free Access Andrew Higson

1 5 From political power to the power of the image: contemporary ‘British’ cinema and the nation’s monarchs Andrew Higson INTRODUCTION: THE HERITAGE OF MONARCHY AND THE ROYALS ON FILM From Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V Shakespeare adaptation in 1989 to the story of the fi nal years of the former Princess of Wales, inDiana in 2013, at least twenty-six English-language feature fi lms dealt in some way with the British monarchy. 1 All of these fi lms (the dates and directors of which will be indi- cated below) retell more or less familiar stories about past and present kings and queens, princes and princesses. This is just one indication that the institution of monarchy remains one of the most enduring aspects of the British national heritage: these stories and characters, their iconic settings and their splendid mise-en-scène still play a vital role in the historical and contemporary experience and projection of British national identity and ideas of nationhood. These stories and characters are also of course endlessly recycled in the pre- sent period in other media as well as through the heritage industry. The mon- archy, its history and its present manifestation, is clearly highly marketable, whether in terms of tourism, the trade in royal memorabilia or artefacts, or images of the monarchy – in paintings, prints, fi lms, books, magazines, televi- sion programmes, on the Internet and so on. The public image of the monarchy is not consistent across the period being explored here, however, and it is worth noting that there was a waning of support for the contemporary royal family in the 1990s, not least because of how it was perceived to have treated Diana.