The Parliamentary Calendar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitution-Making and Reform: Options for the Process

Constitution-making and Reform Options for the Process Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, and Anthony Regan Title Constitution-making and Reform: Options for the Process Authors Michele Brandt, Jill Cottrell, Yash Ghai, Anthony Regan Date November 2011 Publisher Interpeace ISBN 978-2-8399-0871-9 Printed in Switzerland Copyright © Interpeace 2011. All rights reserved. Reproduction of figures or short excerpts from this report is authorized free of charge and without formal written permission, provided that the original source is properly acknowledged, with mention of the complete name of the report, the publisher, and the numbering of the pages or figures. Permission can be granted only to use the material exactly as it is in the report. Figures may not be altered in any way, including the full legends. For media use it is sufficient to cite the source while using the original graphic or figure. This is an Interpeace publication. Interpeace’s publications do not reflect any specific national or political interest. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of Interpeace. For additional permissions or information please e-mail [email protected]. About Interpeace Interpeace has been enabling societies to build lasting peace since 1994. Interpeace is an independent, international peacebuilding organization and a strategic partner of the United Nations. It supports national teams in countries across Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe, and the Middle East. Interpeace also has a thematic program on constitution-making. Over 300 peacebuilding experts work to help their societies manage their internal divisions and conflicts without resorting to violence or coercion. -

View Chamber and Committee Information Document PDF File 0.03

Friday 7 May 2021 CHAMBER AND COMMITTEE INFORMATION This document is compiled by the Table Office as a guide to events likely to take place in and around the Chamber on Tuesday 11 May. It also includes a list of Select Committee meetings planned for that week. From Wednesday 12 May, the Order of Business and Summary Agenda will be published daily. These and other House business papers can be obtained online or in hard copy from the Vote Office. TUESDAY 11 MAY The State Opening of Parliament will take place. The House will meet at 11.25am for the Queen’s Speech. Due to covid-19 restrictions only the Speaker and invited party leaders and Government and Opposition whips will process to hear the speech delivered in the Lords. All other Members must remain in the House of Commons Chamber and not attempt to join the procession. Afterwards the House will suspend until 2.30pm. After introductory statements by the Speaker, the Outlawries Bill will receive its first reading. This is a purely formal proceeding whereby the House asserts its right to deliberate on matters of its own choosing before those proposed by the Government in the Queen’s Speech: no Bill is produced nor is there any debate. The debate on the Queen’s Speech is then opened. Two backbench Members from the Government side will propose and second a Motion for an Address (thanking the Queen for the Speech), after which the Leader of the Opposition and the Prime Minister will speak. Debate on the Queen’s Speech may continue until 10.00pm on this day. -

Sessional Orders and Resolutions

House of Commons Procedure Committee Sessional Orders and Resolutions Third Report of Session 2002–03 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 5 November 2003 HC 855 Published on 19 November 2003 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £11.00 The Procedure Committee The Procedure Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider the practice and procedure of the House in the conduct of public business, and to make recommendations. Current membership Sir Nicholas Winterton MP (Conservative, Macclesfield) (Chairman) Mr Peter Atkinson MP (Conservative, Hexham) Mr John Burnett MP (Liberal Democrat, Torridge and West Devon) David Hamilton MP (Labour, Midlothian) Mr Eric Illsley MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Huw Irranca-Davies MP (Labour, Ogmore) Eric Joyce MP (Labour, Falkirk West) Mr Iain Luke MP (Labour, Dundee East) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Mr Tony McWalter MP (Labour, Hemel Hempstead) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Mr Desmond Swayne MP (Conservative, New Forest West) David Wright MP (Labour, Telford) Powers The powers of the committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 147. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_ committees/procedure_committee.cfm. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Constitution Constitution of Canada Du Canada

SENATE SÉNAT HOUSE OF COMMONS CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES Issue No.9 Fascicule n.9 Thursday, November 20, 1980 Le jeudi 20 novembre 1980 Joint Chairmen: Coprésidents: Sen¡tor Harry Hays Sénateur Harry Hays Serge Joyal, M.P. Serge Joyal, député Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence P rocès - ve rbaux et t émoi gnages of the Special Joint Committee of du Comité mixte spécial the Senate and of du Sénat et de the House of Commons on the la Chambre des communes sur la Constitution Constitution of Canada du Canada RESPECTING: CONCERNANT: The document entitled "Proposed Resolution for a Le document intitulé <Projet de résolution portant Joint Address to Her Majesty the eueen adresse commune à Sa Majesté la Reine respecting the Constitution of Canada" published concernant la Constitution du Canadar, publié par by the Government on October 2,1980 le gouvernement le 2 octobre 1980 iforme edela WITNESSES: TEMOINS: (See back cover) (Voir à l'endos) First Session of the Première session de la Thirty-second Parliament, 1 980 trente-deuxième législature, I 980 I 0s9 SPECIAL JOINT COMMITTEE OF COMITÉ MIXTE SPÉCIAL DU SÉNAT THE SENATE AND OF THE HOUSE ET DE LA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES OF COMMONS ON THE CONSTITUTION SUR LA CONSTITUTION DU CANADA OF CANADA Joint Chairmen; Coprésidents: Senator'Harry Hays Sénateur Harry Hays Serge Joyal, M.P. Serge Joyal, député Re pres e nt i ng t he S e nat e: Représentant le Sénat: Senators: Les sénateurs: Austin Haidasz Muir Rousseau Bielish Lapointe Nieman Tremblay-( l0) Bird Representing the House of Commons: Représentant la Chambre des communes: Messrs. -

Grenzeloos Actuariaat

grenzeloos actuariaat BRON: WIKIPEDIA grenzeloos actuariaat: voor u geselecteerd uit de buitenlandse bladen q STATE OPENING OF PARLIAMENT In the United Kingdom, the State Opening of Parliament is an the Commons Chamber due to a custom initiated in the seventeenth annual event that marks the commencement of a session of the century. In 1642, King Charles I entered the Commons Chamber and Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is held in the House of Lords attempted to arrest five members. The Speaker famously defied the Chamber, usually in late October or November, or in a General King, refusing to inform him as to where the members were hiding. Election year, when the new Parliament first assembles. In 1974, Ever since that incident, convention has held that the monarch cannot when two General Elections were held, there were two State enter the House of Commons. Once on the Throne, the Queen, wearing Openings. the Imperial State Crown, instructs the house by saying, ‘My Lords, pray be seated’, she then motions the Lord Great Chamberlain to summon the House of Commons. PREPARATION The State Opening is a lavish ceremony. First, the cellars of the Palace SUMMONING OF THE COMMONS of Westminster are searched by the Yeomen of the Guard in order to The Lord Great Chamberlain raises his wand of office to signal to the prevent a modern-day Gunpowder Plot. The Plot of 1605 involved a Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, who has been waiting in the failed attempt by English Catholics to blow up the Houses of Commons lobby. -

The Parliamentary Calendar

7 The parliamentary calendar The appointment of the times for the holding of sessions of Parliament, the prorogation of the Parliament and the dissolution of the House, is a matter for decision by the Governor- General. The Constitution states: The Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, and may also from time to time, by Proclamation or otherwise, prorogue the Parliament, and may in like manner dissolve the House of Representatives.1 In practice however these vice-regal prerogatives are exercised with the advice of the Executive Government.2 Once a Parliament (session), or a further session within that Parliament, has commenced, the days and times for the routine meetings and adjournments of the House are a matter for the House to decide, yet in practice, by virtue of its majority support, these decisions rest with the Executive Government. The Constitution also provides that the House of Representatives can continue for no longer than three years from the first meeting of the House.3 The significance of this to the concept of a representative Parliament and Government is that a Parliament is of limited duration on the democratic principle that the electors must be able to express their opinions at regular general elections. On the other hand a Parliament of short fixed-term duration may be viewed as undesirable in that too frequent elections have disruptive and/or negative effects on the parliamentary and governmental processes. Of further significance is the principle that Parliament should be neither out of existence nor out of action for any undue length of time. -

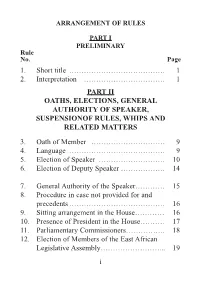

1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY of SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS and RELATED MATTERS 3

ARRANGEMENT OF RULES PART I PRELIMINARY Rule No. Page 1. Short title………………………………… 1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY OF SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS AND RELATED MATTERS 3. Oath of Member ………………………… 9 4. Language ………………………………… 9 5. Election of Speaker ……………………… 10 6. Election of Deputy Speaker ……………… 14 7. General Authority of the Speaker………… 15 8. Procedure in case not provided for and precedents………………………………… 16 9. Sitting arrangement in the House………… 16 10. Presence of President in the House………. 17 11. Parliamentary Commissioners……………. 18 12. Election of Members of the East African Legislative Assembly……………………... 19 i Rule No. Page 13. Election of Members of Pan African Parliament………………………………… 20 14. Role and functions of the Leader of the Opposition ………………………… 20 15. Whips……………………………………… 21 16. Suspension of Rules ……………………… 23 PART III MEETINGS, SITTINGS AND ADJOURNMENT OF THE HOUSE 17. Meetings ………………………………… 24 18. Emergency meetings……………………… 24 19. Sittings of the House……………………… 24 20. Suspension of sittings and recall of House from adjournment ………………… 25 21. Request for recall of Parliament from recess 26 22. Public holidays …………………………… 26 23. Sittings of the House to be public………... 26 24. Quorum of Parliament …………………… 27 PART IV ORDER OF BUSINESS 25. Order of business ………………………… 29 26. Procedure of Business …………………… 31 ii Rule No. Page 27. Order Paper to be sent in advance to Members ………………………………… 32 28. Statement of business by Leader of Government Business …………………… 33 29. Weekly Order Paper ……………………… 33 PART V PETITIONS 30. Petitions…………………………………… 34 PART VI PAPERS 31. Laying of Papers ………………………… 37 32. Mode of Laying of Papers………………… 37 PART VII PRESENTATION OF REPORTS OF PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATIONS ABROAD 33. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY- EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Thursday, 12 February 2015 (Extract from book 2) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier ......................................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education .......................... The Hon. J. A. Merlino, MP Treasurer ....................................................... The Hon. T. H. Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Employment ............ The Hon. J. Allan, MP Minister for Industry, and Minister for Energy and Resources ........... The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Roads and Road Safety, and Minister for Ports ............. The Hon. L. A. Donnellan, MP Minister for Tourism and Major Events, Minister for Sport and Minister for Veterans .................................................. The Hon. J. H. Eren, MP Minister for Housing, Disability and Ageing, Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ........... The Hon. M. P. Foley, MP Minister for Emergency Services, and Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation .................................. The Hon. J. F. Garrett, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ambulance Services .............. The Hon. J. Hennessy, MP Minister for Training and Skills .................................... The Hon. S. R. Herbert, MLC Minister for Local Government, Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Minister for Industrial Relations ................................. The Hon. N. M. Hutchins, MP Special Minister of State .......................................... The Hon. G. Jennings, MLC Minister for Families and Children, and Minister for Youth Affairs ...... The Hon. J. Mikakos, MLC Minister for Environment, Climate Change and Water ................ -

Pro Forma Bills and Parliamentary Independence from the Crown

Pro Forma Bills and Parliamentary Independence from the Crown by Bruce M. Hicks Historically, before the Speech from the Throne may be tabled, let alone debated, in each chamber of Parliament a private members’ public bill was introduced ‘pro forma’ (meaning for form’s sake). This tradition goes back 400 years in Britain and like many ancient traditions some of its significance has been 2009 CanLIIDocs 308 forgotten over time. In 2008, the Canadian Government broke with that tradition and introduced government bills summarizing the claim of privilege it identified as being enjoyed by each chamber. This paper reviews the history of ‘pro forma’ bills, placing them in their original context so as to show that the claim of privileges and rights, all of which were fought for and obtained before the advent of responsible government and are the cornerstones of the legislative branch of government, are more multilayered than is described in these two new bills. It notes that the very act of substituting these new bills is reflective of the increasing domination of the legislative agenda by the Crown. It concludes by recommending that the new format be modified and that MPs and Senators who are not Ministers or Parliamentary Secretaries be selected as movers for the ‘pro forma’ bill, and that bills be chosen that better embrace the full breadth of rights and privileges claimed by the Commons, the Senate and members of Parliament. he following exchange took place when the Mr. Goodale: Mr. Speaker, dealing with Bill C-1 House of Commons met for the first time in the proceedings at the opening of a Parliament following the 2008 election and the Prime is largely a symbolic gesture, as described in T Marleau and Montpetit, to assert Parliament’s Minister moved for leave to introduce Bill C-1, right to act as it sees fit quite apart from what respecting the administration of oaths of office. -

The Governance of Britain

The Governance of Britain Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Justice and Lord Chancellor by Command of Her Majesty July 2007 CM 7170 £13.50 © Crown Copyright 2007 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] Contents Foreword 5 Executive summary 6 Introduction 9 1. Limiting the powers of the executive 15 Moving royal prerogative powers to Parliament 16 Deploying the Armed Forces abroad 18 Ratifying treaties 19 Dissolving Parliament 20 Recalling the House of Commons 21 Placing the Civil Service on a statutory footing 21 Wider review and reforms of the prerogative executive powers 23 Role of the Attorney General 24 The Government’s role in ecclesiastical, judicial and public appointments 25 Appointments in the Church of England 25 Other non-executive appointments 27 Judicial appointments 27 Streamlining public appointments 28 Improving current processes and strengthening the House of Commons’ role 28 Limiting Ministers’ involvement in the granting of honours 30 2. Making the executive more accountable 31 National security 32 Intelligence and Security Committee 32 National Security Strategy 33 Parliament’s scrutiny of Government 34 Departmental debates in the House of Commons 34 Transparency of Government expenditure 35 Independence of the Office for National Statistics 36 Regions and responsibility 37 Regional Ministers 37 Regional select committees 38 Reforming the Ministerial Code 39 3. -

Constitutional Renewal Bill

Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty the Queen July 2009 Cm 7690 £9.50 0 Crown Copyright 2009 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 9780101769020 Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Contents Introduction 3 Protests 7 Attorney General and Prosecutions 14 Courts and Tribunals 20 Ratification of Treaties 30 The Civil Service 35 War Powers 46 Constitutional Renewal? 51 1 Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill 2 Government response to the report of the Joint Committee on the Draft Constitutional Renewal Bill Introduction 1. The Government would like to thank the Joint Committee for their report on the Constitutional Renewal Bill. We are very grateful to the Committee for their thorough consideration of these complex and challenging issues. -

Procedures for Debates, Private Members' Bills and the Powers Of

House of Commons Procedure Committee Procedures for Debates, Private Members’ Bills and the Powers of the Speaker Fourth Report of Session 2002–03 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 19 November 2003 HC 333 Published on 27 November 2003 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £18.50 The Procedure Committee The Procedure Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider the practice and procedure of the House in the conduct of public business, and to make recommendations. Current membership Sir Nicholas Winterton MP (Conservative, Macclesfield) (Chairman) Mr Peter Atkinson MP (Conservative, Hexham) Mr John Burnett MP (Liberal Democrat, Torridge and West Devon) David Hamilton MP (Labour, Midlothian) Mr Eric Illsley MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Huw Irranca-Davies MP (Labour, Ogmore) Eric Joyce MP (Labour, Falkirk West) Mr Iain Luke MP (Labour, Dundee East) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Mr Tony McWalter MP (Labour, Hemel Hempstead) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Mr Desmond Swayne MP (Conservative, New Forest West) David Wright MP (Labour, Telford) Powers The powers of the committee are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 147. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_ committees/procedure_committee.cfm.