Venice Biennale: Staging Nations Emily Lauren Putnam IDSVA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

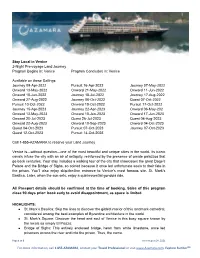

Stay Local in Venice 2-Night Pre-Voyage Land Journey Program Begins In: Venice Program Concludes In: Venice

Stay Local in Venice 2-Night Pre-voyage Land Journey Program Begins in: Venice Program Concludes in: Venice Available on these Sailings: Journey 09-Apr-2022 Pursuit 16-Apr-2022 Journey 07-May-2022 Onward 13-May-2022 Onward 21-May-2022 Onward 11-Jun-2022 Onward 18-Jun-2022 Journey 18-Jul-2022 Journey 17-Aug-2022 Onward 27-Aug-2022 Journey 06-Oct-2022 Quest 07-Oct-2022 Pursuit 10-Oct-2022 Onward 10-Oct-2022 Pursuit 17-Oct-2022 Journey 15-Apr-2023 Journey 22-Apr-2023 Onward 06-May-202 Onward 13-May-2023 Onward 10-Jun-2023 Onward 17-Jun-2023 Onward 20-Jul-2023 Quest 26-Jul-2023 Quest 04-Aug-2023 Onward 22-Aug-2023 Onward 10-Sep-2023 Onward 04-Oct-2023 Quest 04-Oct-2023 Pursuit 07-Oct-2023 Journey 07-Oct-2023 Quest 12-Oct-2023 Pursuit 14-Oct-2023 Call 1-855-AZAMARA to reserve your Land Journey Venice is—without question—one of the most beautiful and unique cities in the world. Its iconic canals infuse the city with an air of antiquity, reinforced by the presence of ornate palazzos that go back centuries. Your stay includes a walking tour of the city that showcases the great Doge’s Palace and the Bridge of Sighs, so coined because it once led unfortunate souls to their fate in the prison. You’ll also enjoy skip-the-line entrance to Venice’s most famous site, St. Mark’s Basilica. Later, when the sun sets, enjoy a quintessential gondola ride. All Passport details should be confirmed at the time of booking. -

Suspension Bridges

Types of Bridges What are bridges used for? What bridges have you seen in real life? Where were they? Were they designed for people to walk over? Do you know the name and location of any famous bridges? Did you know that there is more than one type of design for bridges? Let’s take a look at some of them. Suspension Bridges A suspension bridge uses ropes, chains or cables to hold the bridge in place. Vertical cables are spaced out along the bridge to secure the deck area (the part that you walk or drive over to get from one side of the bridge to the other). Suspension bridges can cover large distances. Large pillars at either end of the waterways are connected with cables and the cables are secured, usually to the ground. Due to the variety of materials and the complicated design, suspension bridges are very expensive to build. Suspension Bridges The structure of suspension bridges has changed throughout the years. Jacob’s Creek Bridge in Pennsylvania was built in 1801. It was the first suspension bridge to be built using wrought iron chain suspensions. It was 21 metres long. If one single link in a chain is damaged, it weakens the whole chain which could lead to the collapse of the bridge. For this reason, wire or cable is used in the design of suspension bridges today. Even though engineer James Finlay promised that the bridge would stay standing for 50 years, it was damaged in 1825 and replaced in 1833. Suspension Bridges Akashi Kaiko Bridge, Japan The world’s longest suspension bridge is the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge in Japan. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal)

Canal Grande (The Grand Canal) Night shot of the Canal Grande or Grand Canal of Venice, Italy The Canal Grande and the Canale della Giudecca are the two most important waterways in Venice. They undoubtedly fall into the category of one of the premier tourist attractions in Venice. The Canal Grande separates Venice into two distinct parts, which were once popularly referred to as 'de citra' and 'de ultra' from the point of view of Saint Mark's Basilica, and these two parts of Venice are linked by the Rialto bridge. The Rialto Bridge is the most ancient bridge in Venice.; it is completely made of stone and its construction dates back to the 16th century. The Canal Grande or the Grand Canal forms one of the major water-traffic corridors in the beautiful city of Venice. The most popular mode of public transportation is traveling by the water bus and by private water taxis. This canal crisscrosses the entire city of Venice, and it begins its journey from the lagoon near the train station and resembles a large S-shape through the central districts of the "sestiere" in Venice, and then comes to an end at the Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute near the Piazza San Marco. The major portion of the traffic of the city of Venice goes along the Canal Grande, and thus to avoid congestion of traffic there are already three bridges – the Ponte dei Scalzi, the Ponte dell'Accademia, and the Rialto Bridge, while another bridge is being constructed. The new bridge is designed by Santiago Calatrava, and it will link the train station to the Piazzale Roma. -

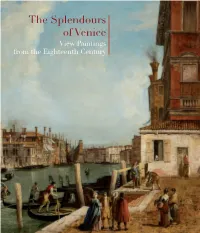

The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century the Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century

The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century Valentina Rossi and Amanda Hilliam DE LUCA EDITORI D’ARTE The Splendours of Venice View Paintings from the Eighteenth Century Lampronti Gallery 1-24 December 2014 9.30 - 6 pm Exhibition curated by Acknowledgements Amanda Hilliam Marcella di Martino, Emanuela Tarizzo, Barbara De Nipoti, the staff of Valentina Rossi Itaca Transport, the staff of Simon Jones Superfreight. Catalogue edited by Amanda Hilliam Valentina Rossi Photography Mauro Coen Matthew Hollow LAMPRONTI GALLERY 44 Duke Street, St James’s London SW1Y 6DD Via di San Giacomo 22 00187 Roma [email protected] [email protected] p. 2: Francesco Guardi, The lagoon with the Forte di S. Andrea, cat. 20, www.cesarelampronti.com detail his exhibition and catalogue commemorates the one-hundred-year anniversary of Lampronti Gallery, founded in 1914 by my Grandfather and now one of the foremost galleries specialising in Italian Old TMaster paintings in the United Kingdom. We have, over the years, developed considerable knowledge and expertise in the field of vedute, or view paintings, and it therefore seemed fitting that this centenary ex- hibition be dedicated to our best examples of this great tradition, many of which derive from important pri- vate collections and are published here for the first time. More precisely, the exhibition brings together a fine selection of views of Venice, a city whose romantic canals and quality of light were never represented with greater sensitivity or technical brilliance than during the eigh- teenth century. -

OCA AR2013.Pdf

p. 4 Director’s Foreword p. 6 Statement of the Board p.12 International Support p. 102 Biennials and Major Solo Exhibitions p. 127 International Studio Programme p. 134 International Residencies Office for Contemporary Art Norway Annual Report 2013 145 p. International Visitor Programme p. 152 OCA Semesterplan p. 164 OCA’s Publication Series Verksted p. 167 Project: ‘On Négritude: A Series of Lectures on the Politics of Art Production in Africa’ p. 171 Project: ‘WORD! WORD? WORD! Office for Issa Samb and the Contemporary Art Undecipherable Form’ Norway p. 182 Project: ‘Fashion: the Fall of an Industry’ p. 198 Project: ‘Anthropocene Observatory: Empire of Calculus’ p. 204 Norway at the Venice Biennale p. 214 OCA in the Press p. 237 Key Figures 2013 p. 257 Organisation and the Board 3 Dear Friend, A Letter to You This is a Letter to You. I have only recently arrived In this regard the necessity to stimulate a reading and we may have not yet met. In fact, we are still and intervention into history in unforeseen ways in the about to, or just have, moment during which becomes vital, so as to nurture and nourish the cre- contours touch, when interiors start to seep and ative potential of the day. Such interventions must blend. We are in the now that ignites a new endeav- be multiple in nature, asymmetric in duration, and our, and anticipates fresh liaisons along the expanse worldly in spirit. Indeed, as practitioners in Norway of a nation and the lands beyond it. Together we repeatedly point to the malleability of how the past start to interweave our thoughts and actions. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself. -

ANSELM KIEFER Education Solo Exhibitions

ANSELM KIEFER 1945 Born in Donaueschingen, Germany Lives and works in France Education 1970 Staatliche Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf, Germany 1969 Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe, Germany Solo exhibitions 2021 Field of the Cloth of Gold, Gagosian Le Bourget, France 2020 Permanent Public Commission, Panthéon, Paris Für Walther Von Der Vogelweide, Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg Villa Kast, Austria Opus Magnum, Franz Marc Museum, Kochel, Germany Superstrings, Runes, the Norns, Gordian Knot, White Cube, London 2019 Couvent de la Tourette, Lyon, France Books and Woodcuts, Foundation Jan Michalski, Montricher, Switzerland; Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo 2018 ARTISTS ROOMS: Anselm Kiefer, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, West Midlands, UK Fugit Amor, Lia Rumma Gallery, Naples For Vicente Huidobro, White Cube, London Für Andrea Emo, Galerie Thaddeus Ropac, Paris Uraeus, Rockefeller Center, New York 2017 Provocations: Anselm Kiefer at the Met Breuer, Met Breuer, New York Anselm Kiefer, for Velimir Khlebnikov, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia Transition from Cool to Warm, Gagosian, New York For Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Voyage au bout de la nuit, Copenhagen Contemporary, Denmark Kiefer Rodin, Rodin Museum, Paris; Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 2016 The Margulies Collection at the Warehouse, Miami Walhalla, White Cube, London The Woodcuts, Albertina Museum, Vienna Regeneration Series: Anselm Kiefer from the Hall Collection, NSU Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 2015 Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris In the -

W E St K U N St O St K U N St

Válogatás a gyűjteményből KUNST The Collection OST on Display KUNST Ludwig Múzeum – Kortárs Művészeti Múzeum WEST Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art WESTKUNST – OSTKUNST Válogatás a gyűjteményből The Collection on Display Válogatás a gyűjteményből The Collection OSTKUNST on Display Ludwig Múzeum – Kortárs Művészeti Múzeum Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art 2018 WESTKUNST Tartalomjegyzék | Contents FABÉNYI Julia előszava | Foreword by Julia FABÉNYI 9 Idővonal | Timeline 14 1 A gyűjtő portréja | A Portrait of the Art Collector 22 2 Az ellenállás művészete | The Art of Opposition 34 2a Koncept és fluxus | Concept Art and Fluxus 38 2b Pop art – Fotórealizmus | Pop Art – Photorealism 64 3 A neoavantgárd művészei | The Artists of the Neo-Avant-Garde 106 3a Az Iparterv-generáció | The Iparterv Generation 112 3b Konceptuális és akció-fotográfia | Conceptual and Action Photography 134 4 Picasso For Ever 1 5 4 5 Rituálék | Rituals 172 6 Idő-kép | The Image of Time 190 7 Hétköznapi rögeszmék – Új szerzemények | Everyday Obsessions – New Acquisitions 208 Műtárgyindex | Artwork Index 236 Rövidítések feloldása | Abbreviation Key 240 ELŐSZŐ FOREWORD Westkunst – Ostkunst Westkunst – Ostkunst Az 1989-ben Budapesten alapított Ludwig The Ludwig Museum, founded in Budapest in Múzeum az első olyan intézmény volt az egy- 1989, was the first institution in the former Social- kori szocialista táborban, amely a kortárs nem- ist bloc to present universal Western art beside zeti művészet mellett az egyetemes, nyugati contemporary national art. The founders, Peter művészetet is bemutatta. Az alapítók, Peter és and Irene Ludwig – after whom the institution is Irene Ludwig – kiknek nevét az intézmény viseli – named – have laid the foundations of the Buda- kiemelkedő, ma már emblematikusnak számító pest Museum with outstanding, emblematic művekkel tették le a budapesti múzeum alapjait. -

Hans Haacke Biography

P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Hans Haacke Biography 1936 Born Cologne, Germany 1956-60 Staatliche Werkakademie (State Art Academy), Kassel, Staatsexamen (equivalent of M.F.A.) 1960-61 Stanley William Hayter's Atelier 17, Paris 1961 Tyler School of Fine Arts, Temple University, Philadelphia 1962 Moves to New York 1963-65 Return to Cologne. Teaches at Pädagogische Hochschule, Kettwig, and other institutions 1966-67 Teaches at University of Washington, Seattle; Douglas College, Rutgers University, New Jersey; Philadelphia College of Art 1967 - 2002 Teaches at Cooper Union, New York (Professor of Art Emeritus) 1973 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1979 Guest Professorship, Gesamthochschule, Essen 1994 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1997 Regents Lecturer, University of California, Berkeley Lives in New York (since 1965) Awards 1960 Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) 1961 Fulbright Fellowship 1973 John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship 1978 National Endowment for the Arts 1991 College Art Association Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement Deutscher Kritikerpreis for 1990 Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts, Oberlin College 1993 Golden Lion (shared with Nam June Paik), Venice Biennale 1997 Kurt-Eisner-Foundation, Munich Honorary Doctorate Bauhaus-Universität Weimar 2001 Prize of Helmut-Kraft-Stiftung, Stuttgart 2002 College Art Association Distinguished Teaching of Art Award 2004 Peter-Weiss-Preis, Bochum 2008 Honorary Doctorate, San Francisco Art Institute -

Export / Import: the Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 Export / Import: The Promotion of Contemporary Italian Art in the United States, 1935–1969 Raffaele Bedarida Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/736 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by RAFFAELE BEDARIDA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 RAFFAELE BEDARIDA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Emily Braun Chair of Examining Committee ___________________________________________________________ Date Professor Rachel Kousser Executive Officer ________________________________ Professor Romy Golan ________________________________ Professor Antonella Pelizzari ________________________________ Professor Lucia Re THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EXPORT / IMPORT: THE PROMOTION OF CONTEMPORARY ITALIAN ART IN THE UNITED STATES, 1935-1969 by Raffaele Bedarida Advisor: Professor Emily Braun Export / Import examines the exportation of contemporary Italian art to the United States from 1935 to 1969 and how it refashioned Italian national identity in the process. -

Plateau of Humankind: the 49Th Venice Biennale’, CIRCA 97, Autumn 2001: 50-51

Maeve Connolly, ‘Plateau of Humankind: The 49th Venice Biennale’, CIRCA 97, Autumn 2001: 50-51. The theme of the 49th Biennale at Venice is Platea dell’umanità, Plateau of Humankind, Plateau der Menschheit, Plateau de l’humanité. Refigured as a ‘plateau’, the exhibition is, according to curator Harald Szeemann, a “place which one looks at and from which one will be seen, a place in which the public onlooker is the protagonist and the measure of things, a place of encounter between artist, work and spectator”.1 But through the transformation of linguistic difference into a brand name, Szeemann inadvertently calls attention to both the imperialist origins of the Biennale itself and the limits of his own utopian project. In the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, critic and philosopher Bazon Brock suggests that a wide range of artistic practices (from Beuys to Benetton advertising campaigns) lead the way towards this “plateau of friendship”.2 But, he suggests, “religious wars (Northern Ireland), wars of nationality (Basque), cultural wars (Ex- Yugoslavia)” will remain until “dogmatic conviction” is given up in favour of friendship. The plateau is therefore reserved for those whose have abandoned excessive conviction, and the particularities of cultural or political difference.3 If Szeemann’s approach to the 1999 Biennale was characterised by disruption of established classifications and divisions, the ‘plateau’ of 2001 is based upon a less focused expansion of these classifications, articulated in various ways. Two newly refurbished venues have been opened at the Arsanale complex, a sixteenth century munitions factory built around a harbour, and these are used to house large scale projects by established artists such as Richard Serra and Ilya and Emilia Kabakov.4 Poetry and ‘net.art’ are represented within the Biennale for the first time and the work of non-Western curators is also recognised, through a parallel exhibition of conceptualism in contemporary African, Authentic/Ex-centric, selected by Salah M.