John Coltrane and the Integration of Indian Concepts in Jazz Improvisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IME Annual Report 2020-2021 Low Size

Supported by Annual Report 2020-2021 Only in the darkness can “ you see the stars. ― Martin Luther King “ Namaste We have collectively endured one of the defining experiences of our life and times. What started off as a pause in the hustle and bustle of daily life has now become a happening that will forever define the way we see the world. Many of us experienced loss – of loved ones, of time, of precious moments, and of a sense of normalcy. There were days when I questioned everything, and felt the meaninglessness of it all. At the same time, I realized that the future is built one day at a time, by the seemingly small actions we take each day; that, as Martin Luther King said, everything that is done in the world is done by hope. And so, we see ourselves looking back at a most strange year, but one that I am glad to report has been extremely productive for the Indian Music Experience Museum, in our mission to build community through music. The team at IME seamlessly adapted to the online world. We ensured the continuity of music education at the Learning Centre. We unveiled two new online exhibits through an important partnership with Google Art and Culture. Our work in preserving musical traditions achieved an important milestone through the creation of an online archive on the life and works of legendary violinist and composer, Mysore T. Chowdiah, in collaboration with the Shankar Mahadevan Academy. We presented a wide variety of talks, discussions, workshops, showcases, and exhibit walkthroughs online, growing our audience beyond the geographic limitations of in-person events. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

New York Meets Vienna

Magazin der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien März 2005 New York meets Vienna Dave Liebman: Zu Wien pflegt er zweifellos eine partikuläre Beziehung. Nicht nur weil er hier – beginnend mit „Lookout Farm“ 1974 im Jazzland – bereits häufig gastiert hat, nein: Wien beherbergt mit dem Porgy & Bess auch jenen Club, von dem er erst kürzlich, im letzten seiner dreimal jährlich verschickten E-Mail-Newsletter, erneut bekannte, dieser sei sein weltweiter Favorit unter den Jazzetablissements. Nun gastiert Dave Liebman mit mehreren Programmen im Magna Auditorium des Musikvereins. Der Mann, der solcherart eine besondere Wien-Affinität zum Ausdruck bringt, ist weit herumgekommen: Dave Liebmans Name hat Rang und Klang in der internationalen Jazz- Community. Als Saxophonist, Komponist und auch als Pädagoge hat er Spuren in der Geschichte hinterlassen, um noch in der Gegenwart Akzente zu setzen. Dave Liebman, das ist jener New Yorker Haudegen, der noch bei den Giganten des Jazz gelernt hat. John Coltrane war es, der den Jugendlichen für jene Musik begeisterte und ihm im persönlichen Kontakt Anregungen mit auf den Weg gab. Zum gemeinsamen Spiel reichte es freilich nicht: Denn als jene Lichtgestalt der sechziger Jahre, Konsensfigur für Avantgardisten und gemäßigte Modernisten, 1967 im Alter von nicht einmal 41 Jahren starb, war Liebman gerade 20 Jahre alt. Lehrling bei Miles Davis Höhere Weihen sollte der in einer liberalen jüdischen Familie in Brooklyn Aufgewachsene durch sein Engagement in der Band des ehemaligen Coltrane-Schlagzeugers Elvin Jones (den er in seinem Nachruf 2004 als eigentlichen musikalischen „Vater“ bezeichnete) erhalten, wie auch durch Miles Davis himself: 1972 als Ersatz für den kurzfristig ausgefallenen Carlos Garnett zu einem Aufnahmetermin für das Meisterwerk „On The Corner“ ins Studio gerufen, gehörte Liebman 1973/74 der Band des genial-schwierigen Trompeters nach dessen Umorientierung hin zum Rock-Jazz an – und erlebte in diesen knapp eineinhalb „Lehrlingsjahren“ (Liebman), die u. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

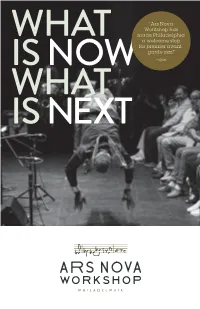

“Ars Nova Workshop Has Made Philadelphia a Welcome Stop For

“Ars Nova Workshop has made Philadelphia a welcome stop WHAT for premier avant- garde jazz." IS NOW —Spin WHAT IS NEXT “Curatorial brilliance” THIS IS —Downbeat OUR Mission AND THIS IS What WE DO Through collaboration and passionate investment, elevates the profile and expands the boundaries of jazz and contemporary music in Philadelphia. We present, on average, 40+ concerts per + year, featuring the biggest names in jazz and Concerts a year contemporary music. Sold Out More than half of our concerts are sold-out shows. We operate through partnerships—with venues, other non-profits, and local and national makers, visionaries, and creatives. We present in spaces throughout Philadelphia with a wide range of capacities, from 100 to 1,300 and more. We are masters at matching the artist with the venue, creating rich context and the appropriate environment for deep listening. OUR CURatoRial and PROGRamminG AMBitions Our logo incorporates a reproduction of a musical line: the iconic title riff from John Coltrane’s manuscript of “A Love Supreme.” While Ars Nova is indebted to this piece and the moment it represents for many reasons, we are especially drawn to the unassuming “ETC.” at the end. Think of everything that “ETC.” can do, promise, and point to: “A Love Supreme” takes off and becomes a new entity, spreading love and possibility and healing and joy and curiosity and discovery and a deeply spiritual present—no longer “just” a phenomenal piece of music that was recorded in a studio one day, but an anthem, a call to a future, a brain- seed in the form of an ear-worm. -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world.