Zhang Peili: Negotiating a Space for Contemporary Art in China with Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Subject Description Form

Form AS 140 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Subject Description Form Please read the notes at the end of the table carefully before completing the form. Subject Code CBS1A20 Subject Title Self-representation in New Media Credit Value 3 Level 1 Pre-requisite / Exclusion Co-requisite/ GEC1A05W Self-representation in New Media Exclusion GEC1A05 Self-representation in New Media CBS1A20M Self-representation in New Media Objectives This subject aims to examine how the emergence of different new media has mediated the conception and production of the self, identity, and autobiography by visual and verbal means. The complex human conditions behind such self-representation from different cultures will be investigated. Intended Learning Upon completion of the subject, students will be able to: Outcomes (a) enhance students’ literacy skills in reading and writing; (Note 1) (b) identify the mediated personal narratives embedded in different types of self-representation in new media; (c) pinpoint the boundary and difference between mere self-expression and performing/advertising the self in new media; (d) analyze how embodied self-expression in new media has transcended traditional means of communication; (e) evaluate critically the merit and limitation of specific forms of self- representation in new media. Subject Synopsis/ 1. Overview about Interpreting Life Narratives in Different Media (1 Indicative Syllabus lecture) (Note 2) 2. Self-representation in Self-portraiture: Identity Construction (2 lectures) Vermeer, Velasquez, Rembrandt, Kathe Kollwitz, Courbet, Cèzanne, Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, Charlotte Salomon, Picasso, Dali, Magritte, Egon Schiele, Frida Kahlo, Francis Bacon, Orlan, Ana Mendieta, Adrian Piper, Yu Hong, Fang Lijun, & Yue Minjun, Song Dong & Wilson Shieh 3. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 03:24:39AM Via Free Access ,

Blood, Sweat and Tears. The Martyred Body in Chinese Performance Art Tania Becker When we speak of offending images in the context of contemporary Chinese art, some of us may remember articles that were published in , voices of outrage in reaction to Zhu Yu’s performance Eating People: Is it art when a man eats a dead baby? london — My God, what kind of society do we live in? A Chinese man eats a dead baby on TV and actually claims it’s art! The announcement alone unleashed one of Great Britain’s hottest debates on the freedom of the media, the press, and art: the British tv Channel wanted to broad- cast the documentary Beijing Swings, which includes photographs of Chinese artist Zhu Yu apparently eating a dead baby. According to Zhu, the corpse is from a miscarriage. In one of the photographs, he’s washing the body in a sink. Another photo shows him biting into a dismembered body part. Zhu has said that the pictures were taken during a perfor- mance titled »Eating Humans« in his house in Beijing. Yesterday, Zhu Yu claimed that as an artist, it’s his job to initiate debates over morality and art. His work involves exploring whether boundaries still exist. It does not, however, seem to bother anyone when this »artist« transgress- es these boundaries. Not even the guardians of the law — because de- spite the fact that artists using human body parts for their art can be sentenced to ten years in prison, nothing happened [...]. Tania Becker - 9783846763452 Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 03:24:39AM via free access , After the images made the rounds in the Internet, the shocking act of consum- ing a fetus met with reactions worldwide. -

Dangerous Art

EXPERIMENTAL EMERGING ART ISSUE 3, 2018 DANGEROUS ART JURIJ KRPAN / ALEX ADRIAANSENS / ROY ASCOTT / DALILA HONORATO / ********** ********** / MARNIX DE NIJS / JULIAN BLAUE / CATHRINE KRAMER / ZACK DENFELD / ZORAN TODOROVIĆ / MARKO MARKOVIĆ / ALEXANDRA MURRAY-LESLIE EE ISSUE 3, 2018 ISSUE 3 INDEX 05 06 10 EE III: DANGEROUS ART TOP 10 - THE MOST CURATING DANGERS Stahl Stenslie DANGEROUS ARTWORKS Jurij Krpan 18 24 28 DANGEROUSLY UNSTABLE CONSCIOUSNESS IN Alex Adriaansens DANGER Roy Ascott 34 40 42 STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE TABOO - TRANSGRESSION ART OF FEAR AS ART - TRANSCENDENCE Marnix de Nijs EE - EXPERIMENTAL EMERGING ART Julian Blaue Dalila Honorato Independent Art Magazine ISSUE 3, 2018: DANGEROUS ART This issue is published by TEKS Publishing WWW.EEJOURNAL.NO ISSN: 2464-448X 46 50 54 FEEDING DANGEROUS IDEAS HUMAN GOURMET EATING YOURSELF © 2018 EE Cathrine Kramer Zoran Todorović Marko Marković Contact: [email protected] and Zack Denfeld EE ISSUE 3 is supported and financed by TEKS - TRONDHEIM ELECTRONIC ART CENTRE WWW.TEKS.NO 60 64 66 FASHIONABLY DANGEROUS EE TATTOO WARNING - UPCOMING Alexandra Murray-Leslie EDITORIAL EE ISSUE 3, 2018 EDITORS LETTER EE III : DANGEROUS ART The EE #3 issue researches dangerous but works so poorly done that it offends works of art and artistic ideas, presenting both qualified as well as uninterested some of the most dangerous contemporary audiences? Such as Fellesskapsprosjektet’s artists, thinkers and actors in art. recent monument in Kvam, Norway? Where a single work of art, a trash-like sculpture Dangerous? What is really dangerous art? made from locally found material, divided Physically threatening performances such the Kvam community into antagonistic a SRL - Survival Research Laboratories- fractions, threatening to tear the social putting the audience’s safety at stake while bonds apart. -

Inha Itsverzeichnis Einleitung Teil A:Die Kunsthistorische Einordnung

Inha Itsverzeichnis Einleitung 10 Teil A:Die kunsthistorische Einordnung derPerformance 1. Performance Art und ihre kunsthistorischen ursprunge 14 1.' Der Begriff Performance '4 1.2 Performative Handlungen im Futurismus ,6 l.3 Dada und seine Foigen ,8 1.4 Vom Bild zur Handlung '9 '.5 Gutai - Performative Aktionen 22 '.6 Happening und Fluxus 26 Teil B: Fragen zum Bildbegrijf und zum Forschungsstand der Bildwissenschajt 2. Grundfragen zum Bildbegriff und zum Forschungsstand der Bildwissenschaft 32 3.Der Bildbegriff in der Performance Art Teil C:Begrijflichkeiten und Definitionen 4. Zeitlichkeit und Wahrnehmung 62 4.1 Zeitlichkeit und Dauer 62 4.2 Wahrnehmung 70 S. Erinnerungsraume und Korperlichkeit 79 5.' Was ist Erinnerung? 79 5.2 korper und Prasenz 85 5.3 Schwellenerfahrung und Katharsis 92 6. Performative Asthetik, Performanz und das Ritual 97 6.' Performative Asthetik und Performanz 97 6.2 Aspekte des Rituellen in der performativen Asthetik 104 6.3 Performative Asthetik in Performance Art, im Theater und im Sport rn Tell D: DerSchmerz alsPhiinomen 11. Schmerz als Mittel fur poli 11.1 Kannibalismus und Aufl: 7. Schmerz - Ein menschliches Phanornen 124 11.2 Humanismus als Grenzu 7.1 Der Schmerz aus medizinischer und neurologischer Sicht 124 11.3 Poesie und Ekel- Zhang 7.2 Schmerzentstehung im Korper 125 1104 Leiden als Krlsenlosung 7.3 Schmerz als philosophisches Phanornen 127 11.5 Der Eiserne Vorhang - P€ 8. Die Universalltat des Schmerzes - Geschichte und Kultur des Leidens 145 12. Schmerz als Todesmetaph 8.1 Die Geschichte des Schmerzes 151 12.1 Tod, vergangllchkelt und 8.2 Heilige und Martyrer - Der Heilige Sebastian und Ron Athey 157 Dan McKereghan 8.3 Der Schmerz der Anderen - Wege der Kommunikation 161 12.2 Verwahrlosung und Den Boris Nieslony Ieii E: Schmerzhajte Bilder in der Performance Art 12.3 Massenmorder und die ~ g. -

Abstracts 2012

100TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE L O S A N G E L E S FEBRUARY 22–25, 2012 ABSTRACTS ABSTRACTS 2012 100th Annual Conference, Los Angeles Wednesday, February 22–Saturday, February 25, 2012 50 Broadway, 21st Floor New York, NY 10004 www.collegeart.org College Art Association 50 Broadway, 21st Floor New York, NY 10004 www.collegeart.org Copyright © 2012 College Art Association All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Sessions are listed alphabetically according to the name of the chair. Abstracts 2012 is produced on a very abbreviated schedule. Although every effort is made to avoid defects, information in this book is subject to change. CAA regrets any editorial errors or omissions. We extend our special thanks to the CAA Annual Conference Committee members responsible for the 2012 program: Sue Gollifer, University of Brighton, vice president for Annual Conference, chair; Sharon Matt Atkins, Brooklyn Museum of Art; Peter Barnet, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Brian Bishop, Framingham State University; Connie Cortez, Texas Tech University; Ken Gonzales-Day, Scripps College; and Sabina Ott, Columbia College Chicago. Regional Representatives: Stephanie Barron, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Margaret Lazzari, University of Southern California. We also thank all the volunteers and staff members who made the conference possible. Cover: Photograph provided by Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library. Design: Ellen Nygaard CAA2012 FEBRUARY 22–25 3 Contents CAA International Committee 11 Concerning the Spiritual in Art: Kandinsky’s 19 Confrontation in Global Art History: Past/Present; Pride/ Radical Work at 100 Prejudice Surrounding Art and Artists Chairs: Susan J. -

A SMALL MAP PIECE of PERFORMANCE ART in CHINA a Study Room Guide by Adele Tan June 2008

A SMALL MAP PIECE OF PERFORMANCE ART IN CHINA A study room guide by Adele Tan June 2008 Let me begin with a fruit. The fruit in this instance is Grapefruit, Yoko Ono´s visionary 1964 book of art- making instructions for everyone. The Chinese word for fruit is guo (果)and like the English word it too means the result or reward of work or activity such as in the word jie guo ( 结果 ). So how does one begin to look at performance art in China in the selection of material available in the Live Art Development Agency library and make it a productive (fruitful) endeavour without taking the exploratory fun out of it? The history of performance art in China is still in the making and so we might do well not to make it too conclusive. With this in mind, we could perhaps play a version of Yoko Ono’s Map Piece from the summer of 1962… Draw an imaginary map. ●Carla Kirkwood, Chinese Performance Artists - Redrawing the Map of Chinese Culture, 2004, A0119 / P0519 ●Li Wei, Li Wei, 2005, P0191 ●Li Wei, Performance Video Works 2001–2004, D0113 ● Zhu Ming, 1994-2006 Art Works, 2007, P089 ●Zhu Ming, Performance Art Works, 1994-2004, 2004, D0265 ●Zhu Ming, Resume, Articles and Major Works – pictures, D0103 ●Zhu Ming, Unknown Area, July 2003, D0104 Kirkwood’s essay in TheatreForum provides an easy entry point into the performance art scene in China since its initial flourish in the late 1980s. She gives a concise history of its development over the past two decades but makes clear to us that from the get-go, performance art is to be taken in China as socio- politically engaged, critically antagonistic and at the forefront of experimental contemporary Chinese art by virtue of a habitual mode of operating in the margins. -

Welcome to the June 2015 Edition of Friends of Japan Featured in This Edition:

Welcome to the June 2015 edition of Friends of Japan Featured in this edition: - Canberra Concert: Joseleo Logdat followed by Re-Inventions Concert: The Philippine Embassy in Canberra in Cooperation with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts: Joseleo Logdat Baritone accompanied by Dr. Raul Navarro Barragga Bay FOUR WINDS PRESENTS: Taikoz workshop and concert Cowra Kensuke Todo Sculpture and Drawings Sydney Japanese Folds Performance: Akio! Conversations through the Asian collections Photographs of women by women, from the Gallery’s collection Exhibition: Go East - The Gene & Brian Sherman Contemporary Asian Art Collection Art Speaks Japanese Comes Alive! Student Contest Brisbane We can make another future: Japanese art after 1989 Exhibition: Time of Others Perth Mariko Mori: Rebirth AJS Tomodachi Lunch Bonsai Society of WA and Bonsai Workshop Inc. Perth Kimono Club Page | 1 Canberra Concert: Joseleo Logdat followed by Re-Inventions Date & Time: 7 June, 2015 (1.30pm-) Venue: High Court of Australia (Parkes Place Parkes Canberra) Ticket: For booking, please visit here. Join Philippine baritone Joseleo Logdat, accompanied on piano by Dr Raul Navarro, in his premier performance in Australia. Logdat will exploit the amazing space of the High Court as he sings some favourite works by Beethoven and Mozart. After completing his Bachelor of Music Major in Voice, where he won the Santa Isabel College Conservatory of Music Gold Medal Award, Logdat finished his Master of Music in Hiroshima, Japan under the tutelage of Hiroharu Orikawa where he was chosen as the best recitalist for 2014. Since then Logdat has performed internationally and recently launched the ‘Musika sa Isla’ classical music festival in his province Marinduque aiming to promote classical music in the provinces. -

C5. Definitive Course Document and Course File

Form AS 140 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Subject Description Form Please read the notes at the end of the table carefully before completing the form. Subject Code CBS1A20M Subject Title Self-representation in New Media Credit Value 3 Level 1 Pre-requisite / Exclusion Co-requisite/ GEC1A05 and GEC1A05W and CBS1A20 Self-representation in New Media Exclusion Objectives This subject aims to examine how the emergence of different new media has mediated the conception and production of the self, identity, and autobiography by visual and verbal means. The complex human conditions behind such self- representation from different cultures will be investigated. Upon completion of the subject, students will be able to: Intended Learning Outcomes (a) identify the mediated personal narratives embedded in different types of self-representation in new media; (Note 1) (b) pinpoint the boundary and difference between mere self-expression and performing/advertising the self in new media; (c) analyze how embodied self-expression in new media has transcended traditional means of communication; (d) evaluate critically the merit and limitation of specific forms of self- representation in new media. 1. Overview about Interpreting Life Narratives in Different Media Subject Synopsis/ (1 lecture) Indicative Syllabus 2. Self-representation in Self-portraiture: Identity Construction (Note 2) (1 lecture) Vermeer, Velasquez, Rembrandt, Kathe Kollwitz, Courbet, Cèzanne, Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, Charlotte Salomon, Picasso, Dali, Magritte, Egon Schiele, Frida Kahlo, Francis Bacon, Orlan, Ana Mendieta, Adrian Piper, Yu Hong, Fang Lijun, & Yue Minjun 3. Self-representation in Photography: Life and Death, and Trauma (1 lecture) Hippolyte Bayard, Eadweard Muybridge, Jhon Coplans, Claude Cahun, Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Alice Odilon, Edward Munch, Andy Warhol, John Heartfield, El Lissitsky, Man Ray, Andre Kertesz, Araki Nobunoshi, Hannah Wilke, Nan Goldin, Jeff Wall, Gilbert and George, Yasumasa Morimura, Xing Danwen & Wang Qingsong 4. -

Une Constance À La Chinoise

Journal of Global Cultural Studies 5 | 2009 : Varia (Re)Inventing "Realities" in China Une constance à la chinoise : Considérations sur l’art performatif extrême chinois ERIK BORDELEAU Résumés Cet article se propose de rendre compte de l’évolution fulgurante de l’art performatif chinois à partir du début des années 90 jusqu’au début des années 2000, période relativement brève mais qui en constitue sans doute l’apogée. La radicalité et le caractère extrêmement controversé de certaines des performances discutées ici nous amène à nous questionner sur ce qui différencie les performances qui se présentent comme expression d’un malaise politico-existentiel et celles qui agissent comme acting-out d’une logique biopolitique. Notre travail s’articulera autour des questions suivantes : quels sont les enjeux impliqués dans l’expositionperformative d’une conduite humaine? Ou dans une optique plus biopolitique : que signifie exposer/ dis-play (de) l’humain? Cette réflexion sur l’art performatif en Chine dans une optique biopolitique et anthropogénétique s’appuiera principalement sur les œuvres de Yang Zhichao, He Yunchang, Zhang Huan, Peng Yu, Sun Yuan et Zhu Yu. At the turn of the 21 st century, Chinese extreme performative art reached unprecedented level of 1 radicality and controversy. In this article, I will try to mark a difference between performances which present themselves or can be interpreted as expressions of political and existential malaise, and those that could be thought of as a sort of acting-out of the biopolitical logic. My article will revolve around the following questions: what is at stake in the performative exhibition of human behaviour, as the Chinese translation of the term “performative art” ( xingwei yishu ) suggest? Or in a more biopolitical perspective: what does it mean to dis-play “some” human? This reflection on Chinese performative art in a biopolitical and anthropogenetical perspective will be based principally on the work of Yang Zhichao, He Yunchang, Zhang Huan, Peng Yu, Sun Yuan and Zhu Yu. -

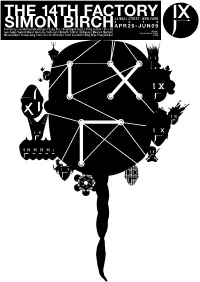

The 14Th Factory

ABOUT THE 14TH FACTORY Entering the world of Simon Birch’s The 14th Factory is to explored both in his paintings (where characters seem to become more than a visitor or a viewer: it is like falling fight their way free of a gravitational pull, wrestling with the into the rabbit hole, transforming into a central player in a medium of the art itself), and in his large-scale installation collaboratively constructed adventure that both embraces projects, most notably HOPE & GLORY (2010), that interlink you and further unfolds through your presence. the artist’s own biography with the rise and fall of mythic and historical pasts. The title The 14th Factory alludes to the historical ‘Thirteen Factories’ (or hongs) of Canton (Guangzhou), China-- In Hong Kong, Birch is inescapably both an insider and an designated trading quarters for Western merchants that outsider, and yet this status gives him a kind of freedom to played an important role in the West’s interactions with move beyond calcified or perceived boundaries. Hong Kong China from the eighteenth century to the First Opium War itself is a kind of nexus of both connectivity and uncertainty, between China and Britain (1849-1842). By decree of the bounded by China and open to the world, poised at a Emperor, the bounded area of the foreign ‘factories’ (an crossroads and re-imagining its own future. From his Hong old word for trading houses) was allowed to exist only Kong base Birch has brought his collaborative energy into outside the main city walls of Canton, thus creating a kind projects -

Chronicle of Events

Chronicle of Events 1949 July January Congress of Chinese Writers and Artists (renamed to The China Federation of Literary 31 The name Beiping (北平) was reverted to and Art Circles) held the First National Exhibi- Peking (北京 adopted to Beijing in 1958) tion of Fine Arts at National Peking Art College. after the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) conquered the city. 2–19 The First National Congress of Litera- ture and Art Workers met in Beijing. A total of six-hundred-fifty delegates February participated the congress, including eighty-eight art workers. The China Fed- 15 The government took over the National eration of Literary and Art Circles Peking Art College. (CFLAC) was founded. 21 China Artists Association (CAA) was founded in Zhongshan Park, Peking. April The Exhibition of New Guohua, featured more October than eighty artists, was held in Zhongshan Park, Beijing. 1 The People’s Republic of China was founded. May November 25 Shanghai was taken over by the PLA. 23 National Peking Art College combined with the art department of North China Univer- sity, establishing the Central Academy of June Fine Arts (CAFA) in 1950. 6 Shanghai prepared to establish the Shanghai Artists Association. # Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2020 459 Y. Zhou, A History of Contemporary Chinese Art, Chinese Contemporary Art Series, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1141-7 460 Chronicle of Events 1950 November CAA published four issues of the art journal 7 National Hangzhou Arts College was Renmin Meishu (People’s Fine Arts). renamed to CAFA East China Campus (renamed to the Zhejiang Fine Arts Academy in 1958, and then to the China Academy of January Art in 1993). -

Syllabus-406 12 29 20 Rev. for 2021S

THTR 406 "Theatre on the Edge" Units: 4 –Course Section #: 63099R Spring 2021—Tuesday/Thursday—4-5:50PM Location: Online, via Blackboard and Zoom Instructor: Dr. Meiling Cheng Office: Via Zoom Office (814 129 6039) Office Hours: By appointment only. Contact Info: [email protected]; cell: 323-683-9259 I will respond to your email queries within 48 hours. Course Assistant: John Allis Contact Info: [email protected] Course Description This course explores the art of theatre on the edge of possibilities. The curriculum proceeds through a series of interrelated themes to examine how the time-based art of theatre intersects with other art forms and absorbs socio-political and technological forces to venture beyond its preexisting boundaries. Highlighting the concept of the edge as a margin, a border, a scar, a threshold, an ecotone, and a membrane, our inquiry investigates various ways in which the edge fosters performing artists' iconoclastic ventures and sustains their constant struggles to evolve beyond the limit of imagination. The course guides the participants to critique, curate, and create theatre on the edge. Per the Professor's research strength, the course will emphasize analytical literacy in reading contemporary visual cultures and will intermittently feature performative artworks from Chinese contemporary time-based art, among other global live art modes. A precautionary note: much of the course material contains intense, gritty, and, for some, potentially offensive materials. Please consider this syllabus a “trigger warning” and guage your receptibility to controversial artworks before you join the class. Your voluntary participation in the course consistitutes an explicit consent to experiencing difficult and/or troubling art.