Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 03:24:39AM Via Free Access ,

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

September/October 2016 Volume 15, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5 INSI DE Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Interview with Raqs Media Collective on the 2016 Shanghai Biennale Artist Features: Cui Xiuwen, Qu Fengguo, Ying Yefu, Zhou Yilun Buried Alive: Chapter 1 US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 C ONT ENT S 23 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Sophia Kidd 23 Qu Fengguo: Temporal Configurations Julie Chun 36 36 Cui Xiuwen Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky 48 Propositioning the World: Raqs Media Collective and the Shanghai Biennale Maya Kóvskaya 59 The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Danielle Shang 48 67 Art Labor and Ying Yefu: Between the Amateur and the Professional Jacob August Dreyer 72 Buried Alive: Chapter 1 (to be continued) Lu Huanzhi 91 Chinese Name Index 59 Cover: Zhang Yu, One Man's Walden Pond with Tire, 2014, 67 performance, one day, Lijiang. Courtesy of the artist. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Chen Ping, David Chau, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist, and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art PRESIDENT Katy Hsiu-chih Chien LEGAL COUNSEL Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C. C. Liu Performance art has a strong legacy in FOUNDING EDITOR Ken Lum southwest China, particularly in the city EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Wallace MANAGING EDITOR Zheng Shengtian of Chengdu. Sophia Kidd, who previously EDITORS Julie Grundvig contributed two texts on performance art in this Kate Steinmann Chunyee Li region (Yishu 44, Yishu 55), updates us on an EDITORS (CHINESE VERSION) Yu Hsiao Hwei Chen Ping art medium that has shifted emphasis over the Guo Yanlong years but continues to maintain its presence CIRCULATION MANAGER Larisa Broyde WEB SITE EDITOR Chunyee Li and has been welcomed by a new generation ADVERTISING Sen Wong of artists. -

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Subject Description Form

Form AS 140 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Subject Description Form Please read the notes at the end of the table carefully before completing the form. Subject Code CBS1A20 Subject Title Self-representation in New Media Credit Value 3 Level 1 Pre-requisite / Exclusion Co-requisite/ GEC1A05W Self-representation in New Media Exclusion GEC1A05 Self-representation in New Media CBS1A20M Self-representation in New Media Objectives This subject aims to examine how the emergence of different new media has mediated the conception and production of the self, identity, and autobiography by visual and verbal means. The complex human conditions behind such self-representation from different cultures will be investigated. Intended Learning Upon completion of the subject, students will be able to: Outcomes (a) enhance students’ literacy skills in reading and writing; (Note 1) (b) identify the mediated personal narratives embedded in different types of self-representation in new media; (c) pinpoint the boundary and difference between mere self-expression and performing/advertising the self in new media; (d) analyze how embodied self-expression in new media has transcended traditional means of communication; (e) evaluate critically the merit and limitation of specific forms of self- representation in new media. Subject Synopsis/ 1. Overview about Interpreting Life Narratives in Different Media (1 Indicative Syllabus lecture) (Note 2) 2. Self-representation in Self-portraiture: Identity Construction (2 lectures) Vermeer, Velasquez, Rembrandt, Kathe Kollwitz, Courbet, Cèzanne, Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, Charlotte Salomon, Picasso, Dali, Magritte, Egon Schiele, Frida Kahlo, Francis Bacon, Orlan, Ana Mendieta, Adrian Piper, Yu Hong, Fang Lijun, & Yue Minjun, Song Dong & Wilson Shieh 3. -

Fresh Meat Rituals: Confronting the Flesh in Performance Art

FRESH MEAT RITUALS: CONFRONTING THE FLESH IN PERFORMANCE ART A THESIS IN Art History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS By MILICA ACAMOVIC B.A., Saint Louis University, 2012 Kansas City, Missouri 2016 © 2016 MILICA ACAMOVIC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FRESH MEAT RITUALS: CONFRONTING THE FLESH IN PERFORMANCE ART Milica Acamovic, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2003 ABSTRACT Meat entails a contradictory bundle of associations. In its cooked form, it is inoffensive, a normal everyday staple for most of the population. Yet in its raw, freshly butchered state, meat and its handling provoke feelings of disgust for even the most avid of meat-eaters. Its status as a once-living, now dismembered body is a viscerally disturbing reminder of our own vulnerable bodies. Since Carolee Schneeman's performance Meat Joy (1964), which explored the taboo nature of enjoying flesh as Schneeman and her co- performers enthusiastically danced and wriggled in meat, many other performance artists have followed suit and used raw meat in abject performances that focus on bodily tensions, especially the state of the body in contemporary society. I will examine two contemporary performances in which a ritual involving the use of raw meat, an abject and disgusting material, is undertaken in order to address the violence, dismemberment and guilt that the body undergoes from political and societal forces. In Balkan Baroque (1997), Marina Abramović spent three days cleansing 1,500 beef bones of their blood and gristle amidst an installation that addressed both the Serbo-Croatian civil war and her personal life. -

Zhang Peili: Negotiating a Space for Contemporary Art in China with Video

30 x 30 (Detail), single-channel video, CRT monitor, 36:49mins, 1988. 《30 x 30》 (细节),单频录像,阴极射线管显示器,36分49秒,1988年。 Zhang Peili: Negotiating a space for contemporary art in China with video John Clark The context for contemporary art The arrival of video art in China cannot be seen in a vacuum. The ground was prepared by changes in exhibition organisation; new generations of post–Cultural Revolution artists, including Zhang Peili; general shifts in art education; and the opening of the economy (and, with that, changes in the organs of cultural control, or at least changes in their manner of operation). Much of the background is covered in an increasingly voluminous literature on Chinese contemporary art in the 1980s and 1990s, which is often articulated around the caesura of the ‘Beijing Incident’ in June 1989, preceded as it was by the China/Avant-Garde exhibition in February 1989.1 In a sense, the art world opened up and established its autonomy during 1985–89, but was then held back sharply in the two years after the ‘Incident’.2 It reopened irreversibly, it appears, after the visits of Deng Xiaoping to Shenzhen in 1992, and his associated speeches.3 95 ZHANG PEILI: FROM PAINTING TO VIDEO The residues of 1989 are many. Principally there was and is an official antipathy for disturbing events or artworks that are socially unexpected, uncontrolled or deliberately shocking. Of course, current taste defines ‘shock’, but the state applies a shifting criterion of public acceptability, some of whose parameters it changes disingenuously or without notice. Radical art or experimental practice outside the academy no longer has any direct connection with formalist avant- gardism, but certainly during the 1990s a socially disturbing quality was attributed to performance art and, to a lesser degree, to installation art. -

Dangerous Art

EXPERIMENTAL EMERGING ART ISSUE 3, 2018 DANGEROUS ART JURIJ KRPAN / ALEX ADRIAANSENS / ROY ASCOTT / DALILA HONORATO / ********** ********** / MARNIX DE NIJS / JULIAN BLAUE / CATHRINE KRAMER / ZACK DENFELD / ZORAN TODOROVIĆ / MARKO MARKOVIĆ / ALEXANDRA MURRAY-LESLIE EE ISSUE 3, 2018 ISSUE 3 INDEX 05 06 10 EE III: DANGEROUS ART TOP 10 - THE MOST CURATING DANGERS Stahl Stenslie DANGEROUS ARTWORKS Jurij Krpan 18 24 28 DANGEROUSLY UNSTABLE CONSCIOUSNESS IN Alex Adriaansens DANGER Roy Ascott 34 40 42 STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE TABOO - TRANSGRESSION ART OF FEAR AS ART - TRANSCENDENCE Marnix de Nijs EE - EXPERIMENTAL EMERGING ART Julian Blaue Dalila Honorato Independent Art Magazine ISSUE 3, 2018: DANGEROUS ART This issue is published by TEKS Publishing WWW.EEJOURNAL.NO ISSN: 2464-448X 46 50 54 FEEDING DANGEROUS IDEAS HUMAN GOURMET EATING YOURSELF © 2018 EE Cathrine Kramer Zoran Todorović Marko Marković Contact: [email protected] and Zack Denfeld EE ISSUE 3 is supported and financed by TEKS - TRONDHEIM ELECTRONIC ART CENTRE WWW.TEKS.NO 60 64 66 FASHIONABLY DANGEROUS EE TATTOO WARNING - UPCOMING Alexandra Murray-Leslie EDITORIAL EE ISSUE 3, 2018 EDITORS LETTER EE III : DANGEROUS ART The EE #3 issue researches dangerous but works so poorly done that it offends works of art and artistic ideas, presenting both qualified as well as uninterested some of the most dangerous contemporary audiences? Such as Fellesskapsprosjektet’s artists, thinkers and actors in art. recent monument in Kvam, Norway? Where a single work of art, a trash-like sculpture Dangerous? What is really dangerous art? made from locally found material, divided Physically threatening performances such the Kvam community into antagonistic a SRL - Survival Research Laboratories- fractions, threatening to tear the social putting the audience’s safety at stake while bonds apart. -

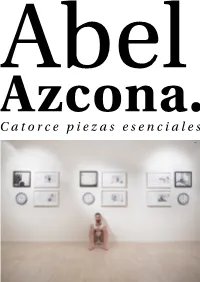

Azcona. Catorce Piezas Esenciales 1 Abel Azcona

Abel Azcona. Catorce piezas esenciales 1 Abel Azcona. Nació el 1 de abril de 1988, fruto de un embarazo no deseado, en la Clínica Montesa de Madrid, institución regentada por una congregación religiosa dirigida a personas en si- tuación de riesgo de exclusión social e indigencia. De padre desconocido, su madre, una joven en ejercicio de la prostitución y politoxicomania llamada Victoria Luján Gutierrez le abandonó en la propia maternidad a los pocos días de nacer. Las religiosas entregaron al recién nacido a un hombre vinculado a su madre, que insistió en su paternidad, a pesar de haber conocido a Victoria ya embarazada y haber sido compañero sentimental esporádico. Azcona se crio desde entonces en la ciudad de Pamplona con la familia de este, igualmente desestructurada y vinculada al narcotráfico y la delincuencia, al estar él entrando y saliendo de prisión de forma continuada. Los primeros cuatro años de vida de Azcona se contextua- lizan en situaciones continuadas de maltrato, abuso y abandono provocadas por diferentes integrantes del nuevo entorno familiar y el paso por varios domicilios, fruto de diferentes retiradas de custodia por instituciones públicas de protección social. El niño se encontraba en situación total de abandono, con signos visibles de abuso, de descuido y de desnutrición, y se aportan testimonios de vecinos y el entorno confirmando que el menor se llega a en- contrar semanas en total soledad en el domicilio, que no cumple las condiciones mínimas de habitabilidad. De los cuatro a los seis años Azcona empieza a ser acogido puntualmente por una familia conservadora navarra que, a los seis años de edad de Azcona, solicitan a instituciones pú- blicas la intervención para convertir la situación en un acogimiento familiar permanente. -

Inha Itsverzeichnis Einleitung Teil A:Die Kunsthistorische Einordnung

Inha Itsverzeichnis Einleitung 10 Teil A:Die kunsthistorische Einordnung derPerformance 1. Performance Art und ihre kunsthistorischen ursprunge 14 1.' Der Begriff Performance '4 1.2 Performative Handlungen im Futurismus ,6 l.3 Dada und seine Foigen ,8 1.4 Vom Bild zur Handlung '9 '.5 Gutai - Performative Aktionen 22 '.6 Happening und Fluxus 26 Teil B: Fragen zum Bildbegrijf und zum Forschungsstand der Bildwissenschajt 2. Grundfragen zum Bildbegriff und zum Forschungsstand der Bildwissenschaft 32 3.Der Bildbegriff in der Performance Art Teil C:Begrijflichkeiten und Definitionen 4. Zeitlichkeit und Wahrnehmung 62 4.1 Zeitlichkeit und Dauer 62 4.2 Wahrnehmung 70 S. Erinnerungsraume und Korperlichkeit 79 5.' Was ist Erinnerung? 79 5.2 korper und Prasenz 85 5.3 Schwellenerfahrung und Katharsis 92 6. Performative Asthetik, Performanz und das Ritual 97 6.' Performative Asthetik und Performanz 97 6.2 Aspekte des Rituellen in der performativen Asthetik 104 6.3 Performative Asthetik in Performance Art, im Theater und im Sport rn Tell D: DerSchmerz alsPhiinomen 11. Schmerz als Mittel fur poli 11.1 Kannibalismus und Aufl: 7. Schmerz - Ein menschliches Phanornen 124 11.2 Humanismus als Grenzu 7.1 Der Schmerz aus medizinischer und neurologischer Sicht 124 11.3 Poesie und Ekel- Zhang 7.2 Schmerzentstehung im Korper 125 1104 Leiden als Krlsenlosung 7.3 Schmerz als philosophisches Phanornen 127 11.5 Der Eiserne Vorhang - P€ 8. Die Universalltat des Schmerzes - Geschichte und Kultur des Leidens 145 12. Schmerz als Todesmetaph 8.1 Die Geschichte des Schmerzes 151 12.1 Tod, vergangllchkelt und 8.2 Heilige und Martyrer - Der Heilige Sebastian und Ron Athey 157 Dan McKereghan 8.3 Der Schmerz der Anderen - Wege der Kommunikation 161 12.2 Verwahrlosung und Den Boris Nieslony Ieii E: Schmerzhajte Bilder in der Performance Art 12.3 Massenmorder und die ~ g. -

Abstracts 2012

100TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE L O S A N G E L E S FEBRUARY 22–25, 2012 ABSTRACTS ABSTRACTS 2012 100th Annual Conference, Los Angeles Wednesday, February 22–Saturday, February 25, 2012 50 Broadway, 21st Floor New York, NY 10004 www.collegeart.org College Art Association 50 Broadway, 21st Floor New York, NY 10004 www.collegeart.org Copyright © 2012 College Art Association All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Sessions are listed alphabetically according to the name of the chair. Abstracts 2012 is produced on a very abbreviated schedule. Although every effort is made to avoid defects, information in this book is subject to change. CAA regrets any editorial errors or omissions. We extend our special thanks to the CAA Annual Conference Committee members responsible for the 2012 program: Sue Gollifer, University of Brighton, vice president for Annual Conference, chair; Sharon Matt Atkins, Brooklyn Museum of Art; Peter Barnet, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Brian Bishop, Framingham State University; Connie Cortez, Texas Tech University; Ken Gonzales-Day, Scripps College; and Sabina Ott, Columbia College Chicago. Regional Representatives: Stephanie Barron, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Margaret Lazzari, University of Southern California. We also thank all the volunteers and staff members who made the conference possible. Cover: Photograph provided by Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library. Design: Ellen Nygaard CAA2012 FEBRUARY 22–25 3 Contents CAA International Committee 11 Concerning the Spiritual in Art: Kandinsky’s 19 Confrontation in Global Art History: Past/Present; Pride/ Radical Work at 100 Prejudice Surrounding Art and Artists Chairs: Susan J. -

NATURALEZA MUERTA Abel Azcona

NATURALEZA MUERTA Abel Azcona El terme natura morta s’aplica a la composició pictòrica que agrupa objectes inanimats, siguin ceràmiques, flors, fruites o animals morts, entre d'altres. El terme bodegó es va encunyar a Espanya al segle XII per designar aquest tipus d'obres. Generalment, el visitant d'una mostra de bodegons trobava el resultat final, només podia presenciar llenços i quadres ja acabats: no era habitual trobar la instal·lació original amb la composició que l’artista havia construït per ser retratada. L'artista Abel Azcona acostuma a desconstruir els termes establerts en l'art tradicional. Aquest cop ens presenta una visió personal de natures mortes contemporànies. Moltes d'elles són resultat d'accions terroristes, catàstrofes naturals, diversos tipus de violència o fins i tot la mort natural. La mort, sigui natural o forçosa, crea una instal·lació viva (i morta). Un resultat estètic, que inclou reflexions polítiques i socials. El terrorisme és un atac directe d’una persona o un col·lectiu (d’Artistes) amb l'objectiu d'aconseguir un impacte eficaç que simbolitzi la seva lluita política de resistència a la norma establerta emprant la violència. Per aconseguir l’objectiu, el terrorista o banda terrorista es val d'estratègies alienes a la lluita armada per acompanyar, de manera ideològica i estètica, l’acció violenta i transportar-la a paràmetres propers a l'admiració: és en l'espectacularitat de l'acte on resideix la veritable crida a l'atenció mediàtica. Si alguna cosa tenen clara els militants del terror és que per aconseguir l'atenció del món han de dissenyar construccions que calin en l’imaginari col·lectiu per causar un trauma social; per això es valen de l'ús i la manipulació de la imatge. -

A SMALL MAP PIECE of PERFORMANCE ART in CHINA a Study Room Guide by Adele Tan June 2008

A SMALL MAP PIECE OF PERFORMANCE ART IN CHINA A study room guide by Adele Tan June 2008 Let me begin with a fruit. The fruit in this instance is Grapefruit, Yoko Ono´s visionary 1964 book of art- making instructions for everyone. The Chinese word for fruit is guo (果)and like the English word it too means the result or reward of work or activity such as in the word jie guo ( 结果 ). So how does one begin to look at performance art in China in the selection of material available in the Live Art Development Agency library and make it a productive (fruitful) endeavour without taking the exploratory fun out of it? The history of performance art in China is still in the making and so we might do well not to make it too conclusive. With this in mind, we could perhaps play a version of Yoko Ono’s Map Piece from the summer of 1962… Draw an imaginary map. ●Carla Kirkwood, Chinese Performance Artists - Redrawing the Map of Chinese Culture, 2004, A0119 / P0519 ●Li Wei, Li Wei, 2005, P0191 ●Li Wei, Performance Video Works 2001–2004, D0113 ● Zhu Ming, 1994-2006 Art Works, 2007, P089 ●Zhu Ming, Performance Art Works, 1994-2004, 2004, D0265 ●Zhu Ming, Resume, Articles and Major Works – pictures, D0103 ●Zhu Ming, Unknown Area, July 2003, D0104 Kirkwood’s essay in TheatreForum provides an easy entry point into the performance art scene in China since its initial flourish in the late 1980s. She gives a concise history of its development over the past two decades but makes clear to us that from the get-go, performance art is to be taken in China as socio- politically engaged, critically antagonistic and at the forefront of experimental contemporary Chinese art by virtue of a habitual mode of operating in the margins. -

Welcome to the June 2015 Edition of Friends of Japan Featured in This Edition:

Welcome to the June 2015 edition of Friends of Japan Featured in this edition: - Canberra Concert: Joseleo Logdat followed by Re-Inventions Concert: The Philippine Embassy in Canberra in Cooperation with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts: Joseleo Logdat Baritone accompanied by Dr. Raul Navarro Barragga Bay FOUR WINDS PRESENTS: Taikoz workshop and concert Cowra Kensuke Todo Sculpture and Drawings Sydney Japanese Folds Performance: Akio! Conversations through the Asian collections Photographs of women by women, from the Gallery’s collection Exhibition: Go East - The Gene & Brian Sherman Contemporary Asian Art Collection Art Speaks Japanese Comes Alive! Student Contest Brisbane We can make another future: Japanese art after 1989 Exhibition: Time of Others Perth Mariko Mori: Rebirth AJS Tomodachi Lunch Bonsai Society of WA and Bonsai Workshop Inc. Perth Kimono Club Page | 1 Canberra Concert: Joseleo Logdat followed by Re-Inventions Date & Time: 7 June, 2015 (1.30pm-) Venue: High Court of Australia (Parkes Place Parkes Canberra) Ticket: For booking, please visit here. Join Philippine baritone Joseleo Logdat, accompanied on piano by Dr Raul Navarro, in his premier performance in Australia. Logdat will exploit the amazing space of the High Court as he sings some favourite works by Beethoven and Mozart. After completing his Bachelor of Music Major in Voice, where he won the Santa Isabel College Conservatory of Music Gold Medal Award, Logdat finished his Master of Music in Hiroshima, Japan under the tutelage of Hiroharu Orikawa where he was chosen as the best recitalist for 2014. Since then Logdat has performed internationally and recently launched the ‘Musika sa Isla’ classical music festival in his province Marinduque aiming to promote classical music in the provinces.