The Winding Road on the Media Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elisa Elamus Kaabliga Kanalipaketid Kanalid Seisuga 01.07.2021

Elisa Elamus kaabliga kanalipaketid kanalid seisuga 01.07.2021 XL-pakett L-pakett M-pakett S-pakett KANALI NIMI KANALI NR AUDIO SUBTIITRID KANALI NIMI KANALI NR AUDIO SUBTIITRID ETV HD 1 EST PBK 60 RUS Kanal 2 HD 2 EST RTR-Planeta 61 RUS TV3 HD 3 EST REN TV 62 RUS ETV2 HD 4 EST NTV Mir 63 RUS TV6 HD 5 EST 3+ HD 66 RUS Kanal 11 HD 6 EST STS 71 RUS Kanal 12 HD 7 EST Dom kino 87 RUS Elisa 14 EST TNT4 90 RUS Cartoon Network 17 ENG; RUS TNT 93 RUS KidZone TV 20 EST; RUS Pjatnitsa 104 RUS Euronews HD 21 ENG Kinokomedia HD 126 RUS CNBC Europe 32 ENG Eesti kanal 150 EST Alo TV 46 EST Meeleolukanal HD 300 EST MyHits HD 47 EST Euronews 704 RUS Deutche Welle 56 ENG Duo 7 HD 934 RUS ETV+ 59 ENG Fox Life 8 ENG; RUS EST Viasat History HD 33 ENG; RUS EST; FIN Fox 9 ENG; RUS EST History 35 ENG; RUS EST Duo 3 HD 10 ENG; RUS EST Discovery Channel 37 ENG; RUS EST TLC 15 ENG; RUS EST BBC Earth HD 44 ENG Nickelodeon 18 ENG; EST; RUS VH1 48 ENG CNN 22 ENG TV7 57 EST BBC World News 23 ENG Orsent TV 69 RUS Bloomberg TV 24 TVN 70 RUS Eurosport 1 HD 28 ENG; RUS 1+2 72 RUS Duo 6 HD 11 ENG; RUS Mezzo 45 FRA FilmZone HD 12 ENG; RUS EST MCM Top HD 49 FRA FilmZone+ HD 13 ENG; RUS EST Trace Urban HD 50 ENG AMC 16 ENG; RUS MTV Europe 51 ENG Pingviniukas 19 EST; RUS Eurochannel HD 52 RUS HGTV HD 27 ENG EST Life TV 58 RUS Eurosport 2 HD 29 ENG; RUS TV XXI 67 RUS Setanta Sports 1 31 ENG; RUS Kanal Ju 73 RUS Viasat Explore HD 34 ENG; RUS EST; FIN 24 Kanal 74 UKR National Geographic 36 ENG; RUS EST Belarus 24 HD 75 RUS Animal Planet HD 38 ENG; RUS KidZone+ HD 503 EST; RUS Travel Chnnel HD 39 ENG; RUS SmartZone HD 508 EST; RUS Food Network HD 40 ENG; RUS Fight Sports HD 916 ENG Investigation Discovery HD 41 ENG; RUS EST VIP Comedy HD 921 ENG; RUS EST CBS Reality 42 ENG; RUS Epic Drama HD 922 ENG; RUS EST National Geographic HD 900 ENG; RUS Arte HD 908 FRA; GER Nat Geo Wild HD 901 ENG; RUS Mezzo Live HD 909 FRA History HD 904 ENG FIN Stingeray iConcerts HD 910 FRA Setanta Sports 1 HD 907 ENG; RUS. -

TALLINNA TEHNIKAÜLIKOOL Infotehnoloogia Teaduskond

TALLINNA TEHNIKAÜLIKOOL Infotehnoloogia teaduskond Arvutitehnika instituut IAG40LT Igor Bõstrov 061652IASB Digitelevisiooni võimalused ja tulevik Bakalaurusetöö Juhendaja: Dotsent Vladimir Viies Tallinn 2015 Bakalaurusetöö ülesanne Üliõpilane: Igor Bõstrov Lõputöö teema eesti keeles: “Digitelevisiooni võimalused ja tulevik” Lõputöö teema inglise keeles: “The future of digital television and it opportunities” Juhendaja (nimi, töökoht, teaduslik kraad, allkiri): Vladimir Viies ATI dotsent PhD Lahendatavad küsimused ning lähtetingimused: Digitelevisioni ajalugu, digitelevisiooni kirjeldamine IPTV näitel, selle omadused, nõuded, arendamise võimalused, IPTV kasutajaliides Elioni näitel, IPTV rakendused Eesti turul ning soovitused IPTV kasutajatele Elioni näitel. 2 Autori deklaratsioon Kinnitan, et antud tööd tegin iseseisvalt, ja varem seda tööd keegi ei ole kaitsmiseks esitanud. Kasutatud teiste autorite tööd, ajakirjad ja kirjandus on selles töös määratletud. Kuupäev allkiri 3 Abstract One popular question for each family, or individual person, who wishes to spend their leisure time for entertainment, sitting at home, or in order to be aware of what has happened in the world, or just to know which weather tomorrow will be - for sure comes to television. Television - is the history of development of technologies. Tube, color image, video recorders, cable, satellites, digital and mobile technologies were revolutionary of his time, not only technical but also social and cultural meaning. Television became the flow of technology scales, has radically changed people's living conditions, creating a completely new options to affect the audience. Digital TV, or digital television, audio and video transmission method using discrete signals, as apposed analog television that uses an analog signal. The question is to what TV should you choose? This is a very personal question, but you have to make your choice easier, in favor of one operator or another, should be a clear understanding of transmission of television and what benefits there are in one way or another. -

DICE Best Practice Guide.Pdf

BEST PRACTICE GUIDE Interactive Service, Frequency Social Business Migration, Policy & Platforms Acceptance Models Implementation Regulation & Business Opportunities BEST PRACTICE GUIDE FOREWORD As Lead Partner of DICE I am happy to present this We all want to reap the economic benefi ts of dig- best practice guide. Its contents are based on the ital convergence. The development and successful outputs of fi ve workgroups and countless discus- implementation of new services need extended sions in the course of the project and in conferences markets, however; markets which often have to be and workshops with the broad participation of in- larger than those of the individual member states. dustry representatives, broadcasters and political The sooner Europe moves towards digital switcho- institutions. ver the sooner the advantages of released spectrum can be realised. The DICE Project – Digital Innovation through Co- operation in Europe – is an interregional network We have to recognise that a pan-European telecom funded by the European Commission. INTERREG as and media industry is emerging. The search for an EU community initiative helps Europe’s regions economies of scale is driving the industry into busi- form partnerships to work together on common nesses outside their home country and to strategies projects. By sharing knowledge and experience, beyond their national market. these partnerships enable the regions involved to develop new solutions to economic, social and envi- It is therefore a pure necessity that regional political ronmental challenges. institutions look across the border and aim to learn from each other and develop a common under- DICE focuses on facilitating the exchange of experi- standing. -

Levi TV Kanalid

levikom.ee 1213 Paksenduse (bold) ja punase teksti tähistusega telekanaleid on võimalik järelvaadata 7 päeva täies mahus (järelvaatamise teenus on eraldi kuutasu eest)! Telekanalite Levi TV Paras Levi TV Priima Levi TV Ekstra sisaldumine pakettides: - Põhikanaleid 33 kanalit 63 kanalit 69 kanalit - Muid kanaleid 5 kanalit 5 kanalit 10 kanalit KÕIK KOKKU: 38 telekanalit 68 telekanalit 79 telekanalit Eesti telekanalid: ETV ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 ✓ ✓ ✓ TV6 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 ✓ ✓ ✓ Alo TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Taevas TV7 ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal ✓ ✓ ✓ Eesti Kanal Pluss ✓ ✓ ✓ (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Eesti kanalid HD formaadis (duplikaadina): ETV HD ✓ ✓ ✓ ETV2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 11 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Kanal 12 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TV3 HD ✓ TV6 HD ✓ (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Laste ja noorte telekanalid: Kidzone ✓ ✓ ✓ Kidzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Smartzone HD ✓ ✓ KiKa HD ✓ ✓ Nick JR ✓ ✓ Nickelodeon ✓ ✓ TEL 1213 TEL +372 684 0678 Levikom Eesti OÜ Pärnu mnt 139C, 11317 Tallinn [email protected] | levikom.ee Pingviniukas ✓ ✓ ✓ Multimania ✓ ✓ ✓ Mamontjonok ✓ ✓ ✓ (4 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (9 kanalit) Filmide ja sarjade telekanalid: Epic Drama HD ✓ ✓ ✓ TLC ✓ ✓ ✓ Sony Channel HD ✓ ✓ Sony Turbo HD ✓ ✓ FOX ✓ ✓ FOX Life ✓ ✓ Filmzone ✓ ✓ Filmzone+ HD ✓ ✓ Kino 24 ✓ ✓ ✓ Pro100TV ✓ ✓ ✓ Dom Kino ✓ ✓ ✓ (5 kanalit) (9 kanalit) (11 kanalit) Sporditeemalised telekanalid: Eurosport 1 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Eurosport 2 HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Setanta Sports HD ✓ ✓ ✓ Fuel TV HD ✓ ✓ Nautical Channel ✓ ✓ (3 kanalit) (5 kanalit) (5 kanalit) Teaduse, looduse ja tõsielu teemalised telekanalid: Discovery -

Tallinna Linna 2020. Aasta Konsolideeritud Majandusaasta Aruande Kinnitamine” LISA

Tallinna Linnavolikogu 17. juuni 2021 otsuse nr 85 “Tallinna linna 2020. aasta konsolideeritud majandusaasta aruande kinnitamine” LISA Tallinna linna 2020. aasta konsolideeritud majandusaasta aruanne Sisukord 1. Tegevusaruanne 5 1.1. Konsolideerimisgrupp ja linnaorganisatsioon 5 1.1.1 Konsolideerimisgrupp 5 1.1.2 Linnaorganisatsiooni juhtimine 7 1.1.3 Töötajaskond 9 1.2. Põhilised finantsnäitajad 13 1.3. Ülevaade majanduskeskkonnast 16 1.4. Riskide juhtimine 18 1.4.1 Ülevaade sisekontrollisüsteemist ja tegevustest siseauditi korraldamisel 18 1.4.2 Finantsriskide juhtimine 20 1.5. Ülevaade Tallinna arengukava täitmisest 22 1.6. Ülevaade linna tütarettevõtjate, linna valitseva mõju all olevate sihtasutuste ja mittetulundusühingu tegevusest 58 1.7. Ülevaade linna olulise mõju all olevate äriühingute ja sihtasutuste tegevusest 72 2. Konsolideeritud raamatupidamise aastaaruanne 73 2.1. Konsolideeritud bilanss 73 2.2. Konsolideeritud tulemiaruanne 74 2.3. Konsolideeritud rahavoogude aruanne (kaudsel meetodil) 75 2.4. Konsolideeritud netovara muutuste aruanne 76 2.5. Eelarve täitmise aruanne 77 2.6. Konsolideeritud raamatupidamise aastaaruande lisad 78 Lisa 1. Arvestuspõhimõtted 78 Lisa 2. Raha ja selle ekvivalendid 85 Lisa 3. Finantsinvesteeringud 86 Lisa 4. Maksu- ja trahvinõuded 87 Lisa 5. Muud nõuded ja ettemaksed 88 Lisa 6. Varud 90 Lisa 7. Osalused valitseva mõju all olevates üksustes 91 Lisa 8. Osalused sidusüksustes 93 Lisa 9. Kinnisvarainvesteeringud 94 Lisa 10. Materiaalne põhivara 95 Lisa 11. Immateriaalne põhivara 98 Lisa 12. Maksu- ja trahvikohustised ning saadud ettemaksed 98 Lisa 13. Muud kohustised ja saadud ettemaksed 99 Lisa 14. Eraldised 100 Lisa 15. Võlakohustised 101 Lisa 16. Tuletisinstrumendid 105 Lisa 17. Maksutulud 105 Lisa 18. Müüdud tooted ja teenused 106 Lisa 19. -

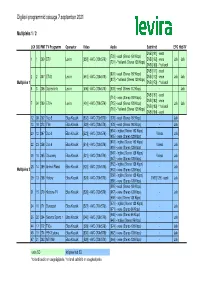

Levira DTT Programmid 09.08.21.Xlsx

Digilevi programmid seisuga 7.september 2021 Multipleks 1 / 2 LCN SID PMT TV Programm Operaator Video Audio Subtiitrid EPG HbbTV DVB [161] - eesti [730] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 1 1 290 ETV Levira [550] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [162] - vene Jah Jah [731] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [163] - *hollandi DVB [171] - eesti [806] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) 2 2 307 ETV2 Levira [561] - AVC (720x576i) DVB [172] - vene Jah Jah [807] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) Multipleks 1 DVB [173] - *hollandi 6 3 206 Digilevi info Levira [506] - AVC (720x576i) [603] - eesti (Stereo 112 Kbps) - - Jah DVB [181] - eesti [714] - vene (Stereo 192 Kbps) DVB [182] - vene 7 34 209 ETV+ Levira [401] - AVC (720x576i) [715] - eesti (Stereo 128 Kbps) Jah Jah DVB [183] -* hollandi [716] - *hollandi (Stereo 128 Kbps) DVB [184] - eesti 12 38 202 Duo 5 Elisa Klassik [502] - AVC (720x576i) [605] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah 13 18 273 TV6 Elisa Klassik [529] - AVC (720x576i) [678] - eesti (Stereo 192 Kbps) - Jah [654] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 20 12 267 Duo 3 Elisa Klassik [523] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [655] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [618] - inglise (Stereo 192 Kbps) 22 23 258 Duo 6 Elisa Klassik [514] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [619] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [646] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 26 10 265 Discovery Elisa Klassik [521] - AVC (720x576i) Videos Jah [647] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [662] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) 28 14 269 Animal Planet Elisa Klassik [525] - AVC (720x576i) - Jah Multipleks 2 [663] - vene (Stereo 128 Kbps) [658] - inglise (Stereo 128 Kbps) -

2020 Annual Report

Radio and Television Commission of Lithuania RADIO AND TELEVISION COMMISSION OF LITHUANIA 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 17 March 2021 No ND-1 Vilnius 1 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE ................................................................................................................ 3 MISSION AND OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................... 5 MEMBERSHIP AND ADMINISTRATION ...................................................................................... 5 LICENSING OF BROADCASTING ACTIVITIES AND RE-BROADCAST CONTENT AND REGULATION OF UNLICENSED ACTIVITIES ............................................................................ 6 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS AND ENFORCEMENT .............................................................. 30 ECONOMIC OPERATOR OVERSIGHT AND CONTENT MONITORING ................................ 33 COPYRIGHT PROTECTION ON THE INTERNET ...................................................................... 41 STAFF PARTICIPATION IN TRAINING AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION EFFORTS ........................................................................................................................................................... 42 COMPETITION OF THE BEST IN RADIO AND TELEVISION PRAGIEDRULIAI ................... 43 PUBLICITY WORK BY THE RTCL .............................................................................................. 46 PRIORITIES FOR 2021 ................................................................................................................... -

Digital Switchover in Central and Eastern Europe

DIGITAL SWITCHOVER IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE: PREMATURE OR KAROL BADLY NEEDED? JAKUBOWICZ 38 - Abstract Preparation for the digital switchover in Central and Karol Jakubowicz was Eastern Europe adds to the complexity of post-Communist (2005-2006) Chairman of the transformation in broadcasting. The following problems are Steering Committee on the apparent: (1) lack of suffi cient understanding of the issues Mass Media and New Com- involved in the digital switch-over, especially as regards the munication Services, Council broadcasting, programming and market issues involved; of Europe; (2) turf wars between broadcasting and telecommuni- e-mail: [email protected]. cations regulatory authorities; (3) the impact of politics on the process of preparation and execution of digital switchover strategies; and (4) in some cases, launching the process prematurely, for inappropriate reasons. Depending Vol.14 (2007), No. 1, pp. 21 1, pp. (2007), No. Vol.14 on one’s point of view, this is either a “premature” digital switchover in countries not yet ready for it, or a case of countries needing a wake-up call to face technological and market realities that they are not responding properly to. Poland is in the process of changing its switchover strat- egy. The process is to start in 2010 with the roll-out of one digital multiplex, covering the whole country, and carrying the existing analogue terrestrial television channels. Plans for further moves are hazy. Meanwhile, many market play- ers are launching alternative projects to take advantage of digital technology, e.g. by means of satellite technology. 21 Preparing for the Digital Switchover in the Context of Post-Communist Transformation In the media fi eld, as elsewhere, post-Communist transformation has meant that Central and Eastern European countries are faced with a major policy over- load. -

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia

Generational Use of News Media in Estonia Contemporary media research highlights the importance of empirically analysing the relationships between media and age; changing user patterns over the life course; and generational experiences within media discourse beyond the widely-hyped buzz terms such as the ‘digital natives’, ‘Google generation’, etc. The Generational Use doctoral thesis seeks to define the ‘repertoires’ of news media that different generations use to obtain topical information and create of News Media their ‘media space’. The thesis contributes to the development of in Estonia a framework within which to analyse generational features in news audiences by putting the main focus on the cultural view of generations. This perspective was first introduced by Karl Mannheim in 1928. Departing from his legacy, generations can be better conceived of as social formations that are built on self- identification, rather than equally distributed cohorts. With the purpose of discussing the emergence of various ‘audiencing’ patterns from the perspectives of age, life course and generational identity, the thesis centres on Estonia – a post-Soviet Baltic state – as an empirical example of a transforming society with a dynamic media landscape that is witnessing the expanding impact of new media and a shift to digitisation, which should have consequences for the process of ‘generationing’. The thesis is based on data from nationally representative cross- section surveys on media use and media attitudes (conducted 2002–2012). In addition to that focus group discussions are used to map similarities and differences between five generation cohorts born 1932–1997 with regard to the access and use of established news media, thematic preferences and spatial orientations of Signe Opermann Signe Opermann media use, and a discursive approach to news formats. -

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List

Asia Expat TV Complete Channel List Australia FOX Sport 502 FOX LEAGUE HD Australia FOX Sport 504 FOX FOOTY HD Australia 10 Bold Australia SBS HD Australia SBS Viceland Australia 7 HD Australia 7 TV Australia 7 TWO Australia 7 Flix Australia 7 MATE Australia NITV HD Australia 9 HD Australia TEN HD Australia 9Gem HD Australia 9Go HD Australia 9Life HD Australia Racing TV Australia Sky Racing 1 Australia Sky Racing 2 Australia Fetch TV Australia Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia AFL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 1 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 2 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 3 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 4 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia Live 5 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 6 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 7 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 8 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Live 9 HD (Live During Events Only) Australia NRL Rugby League 1 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 2 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia NRL Rugby League 3 HD (Only During Live Games) Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 1HD Australia VIP NZ: TVNZ 2HD Australia -

Levikomi Telekanalite Põhipaketid Ja Temaatilised Lisapaketid 01.05.2017

levikom.ee 1213 LEVIKOMI TELEKANALITE PÕHIPAKETID JA TEMAATILISED LISAPAKETID 01.05.2017 LEVIKOM RUBIIN (27 KANALIT): Eesti (8): ETV, ETV2, TV3, KANAL 2, Tallinna TV, TV6, ETV HD, ETV2 HD Vene (1): ETV+ Tõsielu (1): National Geographic Lastele (1): Kidzone Muusika (2): MyHits, iConcert Sport (3): Setanta Sports HD, Fuel TV HD, Motors TV HD Filmid ja sarjad (6): Sony Entertainment, Sony Turbo, FOX, FOX Life, Filmzone, Filmzone+ Eesti looduskaamerad (5): Hooajalised Eesti Looduse Veebikaamerad (Hirve, Hülge, Talilinnu, Käsmu ranna, Pesakasti)* Allajoonitud- ja kaldkirjas märgitud kanalid on järele vaadatavad kuni 1 nädal / kokku 10 telekanalit. *Eesti looduskaamerate puhul on Levikom pildi edastaja ning ei vastuta looduskaamerate pildi kvaliteedi või töökindluse eest. Looduskaamerate valik võib hooajaliselt muutuda. LEVIKOM VIASAT HÕBE (42 KANALIT): Eesti (10): ETV, ETV2, TV3, KANAL 2, Tallinna TV, TV6, Kanal 11, Kanal 12, ETV HD, ETV2 HD Vene (5): ETV+, PBK 1, CTC, REN TV Baltic, TV3+ Uudised (4): CNN, BBC World News, Russia Today, NHK World TV Tõsielu (6): National Geographic, National Geographic Wild, Viasat History, Viasat Nature East, Viasat Explorer Lastele (7): Kidzone, Disney Channel, Disney XD, Disney Junior, NickToons, Nickelodeon, Nickelodeon Junior Muusika (3): MTV Hits, VH1, E! Entertainment Euroopa (3): France24, RTL, Sixx Eesti looduskaamerad (5): Hooajalised Eesti Looduse Veebikaamerad (Hirve, Hülge, Talilinnu, Käsmu ranna, Pesakasti)* Allajoonitud- ja kaldkirjas märgitud kanalid on järele vaadatavad kuni 1 nädal / kokku -

C2WG3 Progress Report

Interreg IIIC DICE Component 3 Working Group 2 Interactive Services, Migration, Implementation & Business Opportunities C3WG2 Final Report: Version: Final 1.0 – 31.10.06 CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 2 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 C3WG2 membership and contributions. ................................................................................................ 7 Meetings............................................................................................................................................. 7 Work Area .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Market Situation in DICE member countries (DTV) ............................................................................... 8 Definition of Interactive TV (i-TV).......................................................................................................... 9 Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Opportunities for i-TV via mobile synergies ......................................................................................... 13 Consumers’ Definition.....................................................................................................................