Edvard Grieg's, Niels Gade and Johann Peter Emilius Hartmann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peer Gynt: Suite No. 1 Instrumentation: Piccolo, 2 Flutes, 2 Oboes, 2

Peer Gynt: Suite No. 1 Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings. Duration: 15 minutes in four movements. THE COMPOSER – EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) – Grieg spent much of the 1870s collaborating with famous countrymen authors. With Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, the composer had hoped to mount a grand operatic history of King Olav Tryggvason but the two artists soon ran afoul of one another. A possible contributing factor was Grieg’s moonlighting project with Henrik Ibsen but, in truth, Bjørnson and the composer had been nursing hurt feelings for a while by the time the latter began to stray. THE MUSIC – As it turned out, Grieg’s back-up plan was more challenging than rewarding at first. He was to compose incidental music that expanded and stitched together the sections of Ibsen’s epic poem. This he did with delight, but soon found the restrictions of the theatrical setting more a burden than a help creatively. “In no case,” he claimed, “had I opportunity to write as I wanted” but the 1876 premiere was a huge success regardless. Grieg seized the chance to re-work some of the music and add new segments during the 1885 revival and did the same in 1902. The two suites he published in 1888 and 1893 likely represent his most ardent hopes for his part of the project and stand today as some of his most potently memorable work. Ibsen’s play depicted the globetrotting rise and fall of a highly symbolic Norwegian anti-hero and, in spite of all the aforementioned struggles, the author could not have chosen a better partner than Grieg to enhance the words with sound. -

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW Begane Grond 1E

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW JULI AUGUSTUS Begane grond Entree Café Woensdag 2 augustus 2017 Trap Trap T Grote Zaal 20.00 uur Zuid Würth Philharmoniker Achterzaal Garderobe Dennis Russell Davies, dirigent Voorzaal Podium Robeco Ray Chen, viool Grote Zaal Summer Restaurant Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791 Symfonie nr. 32 in G, KV 318 (1779) Noord Allegro spiritoso Andante Trap Trap Primo tempo Felix Mendelssohn 1809-1847 Vioolconcert in e, op. 64 (1844) Allegro molto appassionato 1e verdieping Andante Pleinfoyer Allegretto non troppo - Allegro molto vivace Museum- SummerNights Live! foyer PAUZE T Trap Trap Antonín Dvořák 1841-1904 Solistenfoyer Negende symfonie in e, op. 95 ‘Uit de Balkon Zuid Nieuwe Wereld’ (1893) Podium Adagio - Allegro molto Frontbalkon Largo Scherzo: Molto vivace Kleine Zaal Grote Zaal Allegro con fuoco Muziek beleven doet u samen. Veel van Podium Balkon Noord onze bezoekers willen optimaal van de muziek genieten door geconcentreerd en in stilte te Dirigenten- luisteren. Wij vragen u daar rekening mee te Trap foyer Trap houden. WWW.ROBECOSUMMERNIGHTS.NL Informatiebeveiliging in de ambulancezorg Toelichting/TOELICHTING/Biografie//Summary//Concerttip BIOGRAFIE SUMMARYjuli-aug 2015 EN VERDER... In januari 1779 keerde Wolfgang Amadeus het nieuwe vioolconcert was onder meer dat De Würth Philharmoniker draagt de naam When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worked as Social media Robeco Mozart van zijn reis naar Parijs terug in de solist meteen met de deur in huis komt van zijn initiatiefnemer: de Duitse onderne- the court organist for Count Archbishop Salzburg, waar zijn (ongelukkige) dienstver- vallen, dat de solocadens niet aan het eind mer en mecenas Reinhold Würth. Het gloed- Colloredo in Salzburg, he was expected to Meer Robeco SummerNights online! De Robeco SummerNights komen voort uit band bij prins-aartsbisschop Colloredo werd van het eerste deel zit maar veel eerder, en nieuwe orkest, met het juist gebouwde provide new compositions for the court and Volg Het Concertgebouw op social media en een unieke samenwerking tussen Robeco en voortgezet. -

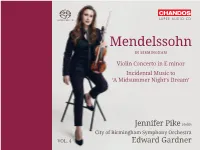

Mendelssohn in BIRMINGHAM

SUPER AUDIO CD Mendelssohn IN BIRMINGHAM Violin Concerto in E minor Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ Jennifer Pike violin City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra VOL. 4 Edward Gardner Painting by Thomas Hildebrandt (1804 – 1874) / Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig / AKG Images, London Felix Mendelssohn, 1845 Mendelssohn, Felix Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847) Mendelssohn in Birmingham, Volume 4 Concerto, Op. 64* 27:56 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur for Violin and Orchestra 1 Allegro molto appassionato – Cadenza ad libitum – Tempo I – Più presto – Sempre più presto – Presto – 12:55 2 Andante – Allegretto non troppo – 9:01 3 Allegro molto vivace 6:00 Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Op. 61† 39:44 (Ein Sommernachtstraum) by William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) 4 Overture (Op. 21). Allegro di molto – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco ritenuto 11:25 5 1 Scherzo (After the end of the first act). Allegro vivace 4:30 6 3 Song with Chorus. Allegro ma non troppo 3:57 7 5 Intermezzo (After the end of the second act). Allegro appassionato – Allegro molto comodo 3:21 3 8 7 Notturno (After the end of the third act). Con moto tranquillo 5:34 9 9 Wedding March (After the end of the fourth act). Allegro vivace 4:30 10 11 A Dance of Clowns. Allegro di molto 1:33 11 Finale. Allegro di molto – Un poco ritardando – A tempo I. Allegro molto 4:28 TT 67:57 Rhian Lois soprano I† Keri Fuge soprano II† Jennifer Pike violin* CBSO Youth Chorus† Julian Wilkins chorus master City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Zoë Beyers leader Edward Gardner 4 Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor / A Midsummer Night’s Dream Introduction fine violinist himself. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Musikstunde Dänische Entdeckungen (1) Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen Von Jörg Lengersdorf Sendung: Montag, 27. Juli 2015 9.05 – 10.00 Uhr Redaktion: Ulla Zierau Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Mitschnitte auf CD von allen Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Musik sind beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden für € 12,50 erhältlich. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde, 27. Juli 2015 Dänische Entdeckungen (1) Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen Man kann beide wohl getrost als die wichtigsten Symphoniker der dänischen Musikgeschichte bezeichnen, Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen. Obwohl letzterer kurzzeitig Schüler des ersteren war, trennt hörbar ein halbes Jahrhundert Kulturhistorie die beiden Männer. Dass Lehrer Gade seinen Schüler Nielsen irgendwie nachhaltig beeinflusst haben könnte, lässt sich musikalisch kaum nachweisen. Niels Wilhelm Gade wurde kurz vor seinem Tod endgültig wahrgenommen als ein großer Konservativer der europäischen Musik, ein Mann der Rückschau ins 19. Jhd. Und es waren just jene Umbruchsjahre, in denen der junge Carl Nielsen die dänische Musik auf ein neues, völlig anders klingendes, Jahrhundert vorbereiten sollte. Beiden Komponisten ist die SWR2 Musikstunde dieser Woche gewidmet, denn beide, Gade wie Nielsen, wurden auf unterschiedliche Art und Weise volkstümlich im nördlichen Nachbarland. -

Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds

EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS By REBEKAH JORDAN A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Rebekah Jordan, April, 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) 1vIc1vlaster University (1vIllSic <=riticisIll) HaIllilton, Ontario Title: Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Author: Rebekah Jordan, B. 1vIus (EastIllan School of 1vIllSic) Sllpervisor: Dr. Hllgh Hartwell NUIllber of pages: v, 129 11 ABSTRACT Although Edvard Grieg is recognized primarily as a nationalist composer among a plethora of other nationalist composers, he is much more than that. While the inspiration for much of his music rests in the hills and fjords, the folk tales and legends, and the pastoral settings of his native Norway and his melodic lines and unique harmonies bring to the mind of the listener pictures of that land, to restrict Grieg's music to the realm of nationalism requires one to ignore its international character. In tracing the various transitions in the development of Grieg's compositional style, one can discern the influences of his early training in Bergen, his four years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and his friendship with Norwegian nationalists - all intricately blended with his own harmonic inventiveness -- to produce music which is uniquely Griegian. Though his music and his performances were received with acclaim in the major concert venues of Europe, Grieg continued to pursue international recognition to repudiate the criticism that he was only a composer of Norwegian music. In conclusion, this thesis demonstrates that the international influence of this so-called Norwegian maestro had a profound influence on many other composers and was instrumental in the development of Impressionist harmonies. -

Edvard Grieg Arranged by Jeff Bailey

String Orchestra TM TEPS TO UCCESSFUL ITERATURE Grade 2½ S S L SO361F • $7.00 Edvard Grieg Arranged by Jeff Bailey Gavotte (from Holberg Suite, Op. 40) Correlated with String Basics, Book 2, page 14 SAMPLE Neil A. Kjos Music Company • Publisher 2 Steps to Successful Literature presents exceptional performance literature - concert and festival pieces - for begin- ning to intermediate string orchestras. Each piece is correlated with a specific location in String Basics – Steps to Success for String Orchestra Comprehensive Method by Terry Shade, Jeremy Woolstenhulme, and Wendy Barden. Literature reinforces musical skills, concepts, and terms introduced in the method. Sometime, a few new concepts are included. They are officially e score. The Arranger Jeff Bailey is a graduate of Old Dominion University with a bachelor’s degree in music composition and University of Virginia with a master of arts in music. He has been teaching middle school string orchestra since 1999, first in Chesterfield Public Schools in Richmond, VA, and currently in Virginia Beach Public Schools. Jeff’s teaching philosophy includes the integration and education of classical music in his middle school orchestra classrooms and often arranges music to support his curriculum. His arrangements and original works have been performed with much acclaim throughout his home state. In addition, he has composed soundtrack music for instructional videos. Jeff has been a performing rock and jazz musician for over three decades, both on guitar and bass. He lives in Virginia Beach, Virginia with his wife and three children. Basics About the Composition Gavotte (from Holberg Suite Op. 40) can be described as charming, warm, lilting, graceful, and enchanting. -

Felix Mendelssohn Overture in C Major, Op. 101, “Trumpet” Felix Mendelssohn Was Born in Hamburg in 1809 and Died in Leipzig in 1847

Felix Mendelssohn Overture in C major, Op. 101, “Trumpet” Felix Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg in 1809 and died in Leipzig in 1847. He composed this work in 1826. The circumstances of its first performance are unknown, though it may have been first heard with a performance of Handel’s Israel in Egypt led by the composer in Düsseldorf the same year. Mendelssohn revised the work in 1833. The Overture is scored for 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings. Mendelssohn composed this work at the age of sixteen, just before he wrote his miraculous Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Some think it was a preliminary study for that masterpiece. If it was, it was not slavishly followed. The subtitle “Trumpet” comes from Mendelssohn’s family always referring to the piece as the “Trumpet Overture,” though hearing the relatively minor role of the trumpets in the work makes one wonder how it came about. Some point to the trumpets’ appearance to punctuate all the major divisions of the work; for others, the prominent interval of the third in the trumpet parts leads to harmonic relationships of a third in the development, but that is getting rather deep into the weeds. In any case, the sixteen year-old Mendelssohn was already a better composer than many ever become, and the Overture is typically brilliant. Mendelssohn himself didn’t think much of it, but it was his father’s favorite work! Concerto for Violin & Orchestra in E minor, Op. 64 Mendelssohn completed his Violin Concerto in 1844, and it was first performed the following year by Ferdinand David, violin, with the Gewandhous Orchestra, Leipzig conducted by Niels Gade. -

Sung Texts CD 4

GRIEG: Complete Orchestral Works CD 4 GRIEGCOMPLETE ORCHESTRAL WORKS Sung Texts CD 4 9 DET FØRSTE MØDE 9 THE FIRST MEETING Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832–1910) Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (1832–1910) Det første mødes sødme, The thrill of love’s first blooming det er som sang i skogen, is like a song in springtime, det er som sang på vågen or golden rays of sunshine i solens sidste rødme, when eventide is looming. det er som horn i uren Like distant horns resounding, de tonende sekunder in tones of muffled thunder, hvori vi med naturen all nature us surrounding, forenes i et under. our souls unite in wonder. English translation: W.H. Halverson DEN BERGTEKNE THE MOUNTAIN THRALL fra M.B. Landstad: Norske Folkeviser from M.B. Landstad: Norske Folkeviser Eg fòr vilt i veduskogin Thro’ the dark wood I did stray, kringum ein elvesteine, The Elfstones above me frowing; jutuldottri narrad meg, Elfinmaids beguiled my way; eg fann inkji vegin heim. never more shall I reach home. Eg fòr vilt i veduskogin Sad ’mid rock and tree I stray’d, kringum ein elve-runne, the elfstones hung darkly o’er me. jutuldottri narrad meg, Thou’st beguiled me, elfin maid; eg hev inkji vegen funnid. homewardpath ne’er shines before me. Eg hev vorid med jutulen I have dwelt with the elfin folk og jutulen etter meg rann, and danced with the queen of their race, gentunn sa’, eg lokkad dei, in her eyes no rapture lies, um eg dei aldri fann. no smile is on her face. Eg hev vorid med jutulen I have dwelt with the elfin folk og jutulen etter meg låg, and danced in their maddening round; gentunn sa’, eg lokkad dei, in the elfin maiden’s arms um eg dei aldri såg. -

Program No / Eng Sommer / Summer 2014 Komponisthjemmene / the Composers’ Homes

PROGRAM NO / ENG SOMMER / SUMMER 2014 KOMPONISTHJEMMENE / THE COMPOSERS’ HOMES LYSØEN OLE BULL MUSEUM TROLDHAUGEN EDVARD GRIEG MUSEUM SILJUSTØL HARALD SÆVERUD MUSEUM Innhold Velkommen 3 Velkommen / Velcome Troldhaugen, Lysøen og Siljustøl er Norges mest betydningsfulle musikkhistoriske kulturminner. De er også noen av Vestlandets 4 Lysøen Ole Bull Museum mest naturskjønne og inspirerende eiendommer. Ole Bull, Edvard 6 Troldhaugen Edvard Grieg Museum Grieg og Harald Sæverud skapte hjem der kunsten, naturen og fantasien kunne møtes. I dag representerer Lysøen, Troldhaugen 8 Siljustøl Harald Sæverud Museum og Siljustøl et unikt musikalsk landskap med til sammen nesten 10 Program Lysøen sommer /summer 2014 1000 mål norsk natur, fascinerende arkitektur og minner om musikerne som erobret verden. 14 Fødselsdagskonsert og hagefest / Birtday concert and garden party at Troldhaugen 16 Konserter på Troldhaugen 2014 / Concerts at Troldhaugen 2014 Velkommen! 18 Konsertbuss til lunsjkonsertene / Concert bus to the lunchtime concerts Sigurd Sandmo 20 Program Troldhaugen: Ukens pianist / Pianist of the week Direktør 33 Grieg in a nutshell – Talks on Grieg Welcome Troldhaugen, Lysøen and Siljustøl are the most significant cultu- ral heritage sites in the history of Norwegian music. They are also perhaps Western Norway’s most scenic and inspirational esta- tes. Ole Bull, Edvard Grieg and Harald Sæverud created homes where art, nature and fantasy came together. Today, Troldhaugen, Lysøen and Siljustøl represent a unique musical landscape with a grand total -

George Balanchine August Bournonville Sasha Janes Jerome Robbins

George Balanchine August Bournonville Sasha Janes THTHEAEATETERR 1716/1/187 Jerome Robbins FOR YOUR INFORMATION Do you want more information about upcoming events at the Jacobs School of Music? There are several ways to learn more about our recitals, concerts, lectures, and more! Events Online Visit our online events calendar at music.indiana.edu/events: an up-to-date and comprehensive listing of Jacobs School of Music performances and other events. Events to Your Inbox Subscribe to our weekly Upcoming Events email and several other electronic communications through music.indiana.edu/publicity. Stay “in the know” about the hundreds of events the Jacobs School of Music offers each year, most of which are free! In the News Visit our website for news releases, links to recent reviews, and articles about the Jacobs School of Music: music.indiana.edu/news. Musical Arts Center The Musical Arts Center (MAC) Box Office is open Monday – Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Call 812-855-7433 for information and ticket sales. Tickets are also available at the box office three hours before any ticketed performance. In addition, tickets can be ordered online at music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. Entrance: The MAC lobby opens for all events one hour before the performance. The MAC auditorium opens one half hour before each performance. Late Seating: Patrons arriving late will be seated at the discretion of the management. Parking Valid IU Permit Holders access to IU Garages EM-P Permit: Free access to garages at all times. Other permit holders: Free access if entering after 5 p.m. -

Fiery Nielsen Sparks Nordic Opener from Chicago Philharmonic by Lawrence A

Fiery Nielsen sparks Nordic opener from Chicago Philharmonic By Lawrence A. Johnson Mon Sep 22, 2014 at 11:52 am One could put together a notably adventurous season just by combining the repertory of Chicago’s top suburban orchestras. The fact that most offer consistently excellent playing as well as thought- provoking programs makes musical excursions outside the city even more essential. The Chicago Philharmonic opened its 25th anniversary season Sunday night with a “Nordic” program of intriguing yet accessible rarities that could serve as a model of its kind. In its second season under Scott Speck, the orchestra was in characteristic top form with boldly projected and largely polished performances at Pick-Staiger Hall, even if the evening overall proved something of a mixed bag. With partial sponsorship from the Danish embassy, the main works of the evening offered music from the country’s two leading composers, Carl Nielsen and Niels Gade. As Speck noted in his informed and informal verbal notes, Nielsen’s distinctive voice was largely formed even in his earliest works. The Symphony No. 1, written at age 27, showcases Nielsen’s style—the edgy, bustling energy, noodling, rhapsodic wind lines, and vaulting key changes, the First Symphony moving from G minor to C major over its four movements. Nielsen’s first of six works in the genre is a score brimming with confidence, and Speck and the Scott Speck opened the Chicago Philharmonic musicians served up a lively and idiomatic performance, the outer movements Philharmonic’s 25th season with a imbued with ample vitality and swagger. -

Edvard Grieg (1843 - 1907)

EDVARD GRIEG (1843 - 1907) When Edvard Grieg grew up, Bergen was a small and busy European town. All through its past as a Hanseatic city, Bergen had established a net of connections that made it the only continental Norwegian city. The main business was the trade with fish and other products typical for the coast. There was a close contact with the rest of Europe, a fact that is easily retraceable in the origin of the bergener. Most of the families within the city limits had ancestors in Denmark, Germany, Scotland, England, the Netherlands and other European nations. Bergen was also a meltingpot for the population along the Norwegian coast. Edvard Griegøs family was a typical Bergen- family: His great grandfather Alexander Greig (later changed to Grieg) came to the city from Cairnbulg close to Aberdeen in Scotland in the 1770s. He founded the family business, which was trade with dried fish and lobster across the North sea. The raising of a child in a bourgeois family in the 19th century Norway often included teaching of music or other forms of art. Edvard Grieg´s grandparents were active in the society of music "Musikkselskapet Harmonien", one of the worlds oldest orchestras, founded in 1765. Edvard Grieg was also so lucky to have the best piano teacher in Bergen as a mother. Gesine Hagerup had studied at the musicconservatory in Hamburg, Germany, an education that usually was offered only to men. She played with "Harmonien" and at chamber music concerts in Bergen. CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH Edvard Grieg was born in Bergen 15th of June 1843, in the family´s house in Strandgaten 152.