Felix Mendelssohn Overture in C Major, Op. 101, “Trumpet” Felix Mendelssohn Was Born in Hamburg in 1809 and Died in Leipzig in 1847

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW Begane Grond 1E

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW JULI AUGUSTUS Begane grond Entree Café Woensdag 2 augustus 2017 Trap Trap T Grote Zaal 20.00 uur Zuid Würth Philharmoniker Achterzaal Garderobe Dennis Russell Davies, dirigent Voorzaal Podium Robeco Ray Chen, viool Grote Zaal Summer Restaurant Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791 Symfonie nr. 32 in G, KV 318 (1779) Noord Allegro spiritoso Andante Trap Trap Primo tempo Felix Mendelssohn 1809-1847 Vioolconcert in e, op. 64 (1844) Allegro molto appassionato 1e verdieping Andante Pleinfoyer Allegretto non troppo - Allegro molto vivace Museum- SummerNights Live! foyer PAUZE T Trap Trap Antonín Dvořák 1841-1904 Solistenfoyer Negende symfonie in e, op. 95 ‘Uit de Balkon Zuid Nieuwe Wereld’ (1893) Podium Adagio - Allegro molto Frontbalkon Largo Scherzo: Molto vivace Kleine Zaal Grote Zaal Allegro con fuoco Muziek beleven doet u samen. Veel van Podium Balkon Noord onze bezoekers willen optimaal van de muziek genieten door geconcentreerd en in stilte te Dirigenten- luisteren. Wij vragen u daar rekening mee te Trap foyer Trap houden. WWW.ROBECOSUMMERNIGHTS.NL Informatiebeveiliging in de ambulancezorg Toelichting/TOELICHTING/Biografie//Summary//Concerttip BIOGRAFIE SUMMARYjuli-aug 2015 EN VERDER... In januari 1779 keerde Wolfgang Amadeus het nieuwe vioolconcert was onder meer dat De Würth Philharmoniker draagt de naam When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worked as Social media Robeco Mozart van zijn reis naar Parijs terug in de solist meteen met de deur in huis komt van zijn initiatiefnemer: de Duitse onderne- the court organist for Count Archbishop Salzburg, waar zijn (ongelukkige) dienstver- vallen, dat de solocadens niet aan het eind mer en mecenas Reinhold Würth. Het gloed- Colloredo in Salzburg, he was expected to Meer Robeco SummerNights online! De Robeco SummerNights komen voort uit band bij prins-aartsbisschop Colloredo werd van het eerste deel zit maar veel eerder, en nieuwe orkest, met het juist gebouwde provide new compositions for the court and Volg Het Concertgebouw op social media en een unieke samenwerking tussen Robeco en voortgezet. -

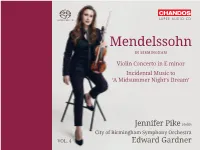

Mendelssohn in BIRMINGHAM

SUPER AUDIO CD Mendelssohn IN BIRMINGHAM Violin Concerto in E minor Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ Jennifer Pike violin City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra VOL. 4 Edward Gardner Painting by Thomas Hildebrandt (1804 – 1874) / Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig / AKG Images, London Felix Mendelssohn, 1845 Mendelssohn, Felix Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847) Mendelssohn in Birmingham, Volume 4 Concerto, Op. 64* 27:56 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur for Violin and Orchestra 1 Allegro molto appassionato – Cadenza ad libitum – Tempo I – Più presto – Sempre più presto – Presto – 12:55 2 Andante – Allegretto non troppo – 9:01 3 Allegro molto vivace 6:00 Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Op. 61† 39:44 (Ein Sommernachtstraum) by William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) 4 Overture (Op. 21). Allegro di molto – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco ritenuto 11:25 5 1 Scherzo (After the end of the first act). Allegro vivace 4:30 6 3 Song with Chorus. Allegro ma non troppo 3:57 7 5 Intermezzo (After the end of the second act). Allegro appassionato – Allegro molto comodo 3:21 3 8 7 Notturno (After the end of the third act). Con moto tranquillo 5:34 9 9 Wedding March (After the end of the fourth act). Allegro vivace 4:30 10 11 A Dance of Clowns. Allegro di molto 1:33 11 Finale. Allegro di molto – Un poco ritardando – A tempo I. Allegro molto 4:28 TT 67:57 Rhian Lois soprano I† Keri Fuge soprano II† Jennifer Pike violin* CBSO Youth Chorus† Julian Wilkins chorus master City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Zoë Beyers leader Edward Gardner 4 Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor / A Midsummer Night’s Dream Introduction fine violinist himself. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Concerto And

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Concerto and Recital Works by Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Poulenc and Rachmaninoff A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Music, Performance by Peter Shannon May 2016 The graduate project of Peter Shannon is approved: _____________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Soo-Yeon Chang Date _____________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Alexandra Monchick Date _____________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Dmitry Rachmanov, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Table of Contents Signature Page ii Abstract iv Section 1: Toccata in F-sharp Minor BWV 910 by J.S. Bach 1 Section 2: Piano Sonata Op. 109 in E major by L.V. Beethoven 4 Section 3: Variations Sérieuses in D minor by Felix Mendelssohn 7 Section 4: Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor by Frédéric Chopin 9 Section 5: Barcarolle in F-sharp major by Frédéric Chopin 10 Section 6: Napoli Suite, FP 40 by Francis Poulenc 13 Section 7: Etude-Tableau Op. 39 no. 9 by Sergei Rachmaninoff 17 Bibliography 20 Appendix A: Program I (Concerto) 21 Appendix B: Program II (Solo Recital) 22 iii Abstract Recital and Concerto Works by Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Poulenc and Rachmaninoff By Peter Shannon Master of Music in Music, Performance Johann Sebastien Bach (1685-1750) explored the genres and forms of the Baroque period with astonishing complexity and originality. Bach used the form of the toccata to couple the rigorous logic of Baroque counterpoint to the fantastic possibilities of improvisational harmony. The Piano Sonata Op. 109 in E major is the first of the final three piano sonatas by the German composer Ludwig van Beethoven. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Musikstunde Dänische Entdeckungen (1) Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen Von Jörg Lengersdorf Sendung: Montag, 27. Juli 2015 9.05 – 10.00 Uhr Redaktion: Ulla Zierau Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Mitschnitte auf CD von allen Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Musik sind beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden für € 12,50 erhältlich. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde, 27. Juli 2015 Dänische Entdeckungen (1) Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen Man kann beide wohl getrost als die wichtigsten Symphoniker der dänischen Musikgeschichte bezeichnen, Niels Wilhelm Gade und Carl Nielsen. Obwohl letzterer kurzzeitig Schüler des ersteren war, trennt hörbar ein halbes Jahrhundert Kulturhistorie die beiden Männer. Dass Lehrer Gade seinen Schüler Nielsen irgendwie nachhaltig beeinflusst haben könnte, lässt sich musikalisch kaum nachweisen. Niels Wilhelm Gade wurde kurz vor seinem Tod endgültig wahrgenommen als ein großer Konservativer der europäischen Musik, ein Mann der Rückschau ins 19. Jhd. Und es waren just jene Umbruchsjahre, in denen der junge Carl Nielsen die dänische Musik auf ein neues, völlig anders klingendes, Jahrhundert vorbereiten sollte. Beiden Komponisten ist die SWR2 Musikstunde dieser Woche gewidmet, denn beide, Gade wie Nielsen, wurden auf unterschiedliche Art und Weise volkstümlich im nördlichen Nachbarland. -

Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds

EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS By REBEKAH JORDAN A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Rebekah Jordan, April, 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) 1vIc1vlaster University (1vIllSic <=riticisIll) HaIllilton, Ontario Title: Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Author: Rebekah Jordan, B. 1vIus (EastIllan School of 1vIllSic) Sllpervisor: Dr. Hllgh Hartwell NUIllber of pages: v, 129 11 ABSTRACT Although Edvard Grieg is recognized primarily as a nationalist composer among a plethora of other nationalist composers, he is much more than that. While the inspiration for much of his music rests in the hills and fjords, the folk tales and legends, and the pastoral settings of his native Norway and his melodic lines and unique harmonies bring to the mind of the listener pictures of that land, to restrict Grieg's music to the realm of nationalism requires one to ignore its international character. In tracing the various transitions in the development of Grieg's compositional style, one can discern the influences of his early training in Bergen, his four years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and his friendship with Norwegian nationalists - all intricately blended with his own harmonic inventiveness -- to produce music which is uniquely Griegian. Though his music and his performances were received with acclaim in the major concert venues of Europe, Grieg continued to pursue international recognition to repudiate the criticism that he was only a composer of Norwegian music. In conclusion, this thesis demonstrates that the international influence of this so-called Norwegian maestro had a profound influence on many other composers and was instrumental in the development of Impressionist harmonies. -

Joe Gaylon Williams in a Voice Recital

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Concert Performances, Programs, and Posters Division of Music 5-7-1968 Joe Gaylon Williams in a Voice Recital Joe Gaylon Williams Ouachita Baptist University William Borland Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/music Part of the Music Education Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Joe Gaylon and Borland, William, "Joe Gaylon Williams in a Voice Recital" (1968). Concert Performances, Programs, and Posters. 250. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/music/250 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Division of Music at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Concert Performances, Programs, and Posters by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUACHITA BAPTIST UNIVERSITY Division of Fine Arts presents JOE GAYLON WILLIAMS Bass-Baritone assisted by Bill Borland, Pianist MITCHELL HALL May 7, 1968 Eight 0'clock PROGRAM I SAMSON G. F. Handel (1685-1759) "Honor and Arms" ST. PAUL Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) "0 God Have Mercy" n LES HUGENOTS Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864) "Piff, Paff'' FIDELIO Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) "Hat man nicht auch Gold daneben" m Se tu m'ami Giovanni Pergolesi (1710-1736) Einnerung Johannes Brahms ( 1833-1897) Der Wanderer Franz Schubert (1797-1828) IV Und willst du deinem Liebsten sterben sehen Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) Les Cloches Claude Debussy ( 1862-1918) Where Am I Going? James Heller (1892- ) The Flea Modest Moussorgsky (1839-1381) This recital is in partial fulfillment for the Bachelor l'f Music degree in Church Music. -

Fanny Mendelssohn

The Akron Symphony Meet the Composer - Fanny Mendelssohn Born: November 14, 1805 Died: May 14, 1847 Fanny Mendelssohn was a German pianist and composer and the older sister of the well-known composer, Felix Mendelssohn. The two siblings were very close. She received a quality musical education, first taking piano les- sons from her mother and later studying piano and composition with other teachers. Due to social conventions of the time re- garding the roles of women, some of her compositions were published under her brother’s name. Fanny’s works were often played alongside those of her brother on the family’s Sunday concert series. In 1829, Fanny married Wilhelm Hensel. Her husband was sup- portive and encouraging of her musical work. Before her death Fanny Mendelssohn she composed more than 460 pieces of music, mostly songs and piano pieces. In 1846, a collection of her songs was published. Since the 1980s her works have become better known through performances and recordings. In May 2018, the Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn Museum was opened in Hamburg, Germany. The Piano The piano was invented by Bartolomeo Cristofori in Italy around 1700. There were several innovations to the instrument during the 1800s. These include a cast iron frame and the use of aliquot strings (unstruck strings that reinforce the tone). These innovations gave the instrument a more powerful sound. During this time the family piano played a similar role to that of the radio in the 19th century. The family would frequently gather around the instrument for an enjoyable musical evening. Timeline 1805 - Fanny Mendelssohn is born in Hamburg, Germany 1807 – Lord Nelson defeats the combined French and Spanish fleets in the Battle of Trafalgar 1809 – Mary Kies becomes the first woman in the U.S. -

German Virtuosity

CONCERT PROGRAM III: German Virtuosity July 20 and 22 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Concert Program III continues the festival’s journey from the Classical period Thursday, July 20 into the nineteenth century. The program offers Beethoven’s final violin 7:30 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School sonata as its point of departure into the new era—following a nod to the French Saturday, July 22 virtuoso Pierre Rode, another of Viotti’s disciples and the sonata’s dedicatee. In 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton the generation following Beethoven, Louis Spohr would become a standard- bearer for the German violin tradition, introducing expressive innovations SPECIAL THANKS such as those heard in his Double String Quartet that gave Romanticism its Music@Menlo dedicates these performances to the following individuals and musical soul. The program continues with music by Ferdinand David, Spohr’s organizations with gratitude for their generous support: prize pupil and muse to the German tradition’s most brilliant medium, Felix July 20: The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Mendelssohn, whose Opus 3 Piano Quartet closes the program. July 22: Alan and Corinne Barkin PIERRE RODE (1774–1830) FERDINAND DAVID (1810–1873) Caprice no. 3 in G Major from Vingt-quatre caprices en forme d’études for Solo Caprice in c minor from Six Caprices for Solo Violin, op. 9, no. 3 (1839) CONCERT PROGRAMS CONCERT Violin (ca. 1815) Sean Lee, violin Arnaud Sussmann, violin FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Piano Quartet no. 3 in b minor, op. 3 (1825) Violin Sonata no. -

DER RHEIN Ein Literarischer Reiseführer

DER RHEIN Ein literarischer Reiseführer Herausgegeben von Gertrude Cepl-Kaufmann und Hella-Sabrina Lange INHALT Vorwort XIII Der Rhein - Ein universales Natur- und Kulturereignis 2 Der Rhein (Friedrich Hölderlin) 2 Der Ursprung des Rheins (G. I. Caesar) 8 Von den Elementen (Hildegard von Bingen) 9 Der Rheinstrom (Joost van den Vondel) 9 Rheinweinlied (Matthias Claudius) 11 Der Rhein. Deutschlands Schutzgeist (Germaine de Stael) . 12 Der Rhein (Wilhelm von Humboldt) 13 Der Rhein. Ein Abbild der deutschen Geschichte (Friedrich Schlegel) 13 Beim Anblick des königlichen Rheins (Joseph von Eichendorff) 14 Baedekers Rheinreise von Basel bis Düsseldorf (Karl Baedeker) 15 Der Rhein als Quelle der Dichtkunst (Alexandre Dumas d.Ä.) 16 Der Rhein und Europa (Victor Hugo) 16 Der Rheinreisende, wie er sein soll (Georg Weerth) 17 An den Rhein (Herbert Eulenberg) 17 Vater Rhein (Kurt Schwitters) 18 Der Rhein und Deutschlands Stämme (Kurt Tucholsky) ... 19 Carl Zuckmayers Blick auf den Rhein (Carl Zuckmayer) ... 21 Vom Rhein - vom Abendland (Carl Zuckmayer) 21 •Rheinmärchen (Erich Fried) 22 "^Vom Quellgebiet über den Bodensee zum Oberrhein 24 IViamala! (Gottfried Keller) 24 [Bin Amerikaner am Schweizer Rhein (James Fenimore Cooper) 25 Der Salm (Christian Morgenstern) 26 V Am Zusammenfluss von Vorder- und Hinterrhein (Alfons Paquet) 27 Das Fürstentum Liechtenstein (Ernst Glaeser) 28 Bodensee-Gedanken (Johanna Walser) 28 Abend am Bodensee (Ernst Toller) 29 Am Bodensee einst (Johannes R. Becher) 30 Ein Bummeltag (Hermann Hesse) 30 Sonntagmittag (Martin Walser) 31 Mainau (Rudolf Borchardt) 32 Meersburg (Harriet Sträub) 32 Theodor Fontane am Rheinfall bei Schaffhausen (Theodor Fontane) 33 Der Rhein bei Schaffhausen (Wilhelm Heinse) 34 Das vallis rheni (Karl Simrock) 35 Am Bodensee (Ferdinand Hardekopf) 36 Der Geruch des Wassers (John von Düffel) 37 Basel (Friedrich Schlegel) 37 Das Eisass und Straßburg 40 Eisass (Sebastian Münster) 40 Am jungen Rhein (Marie Luise Kaschnitz) 40 Friedrich Schinkel in Kehl und Straßburg (Friedrich Schinkel) 42 Gespenstischer Rhein. -

Purcell, Handel, Haydn, and Mendelssohn Anniversary Reflections

Purcell, Handel, Haydn, and Mendelssohn Anniversary Reflections March 2009 Martin Adams Trinity College, Dublin "That what took least, was really best": tensions between the private and public aspects of Purcell's compositional thought. Roger North remembered that Purcell "used to mark what did not take for the best musick, it being his constant observation that what took least, was really best." Purcell's penchant for complexity has been discussed widely; and Alan Howard has recently said that aspects of the composer's practice set him "somewhat apart from contemporary composers and, even more importantly, from the expectations of his audiences." They also set him somewhat apart from the other composers in this conference. My paper will argue that this apartness is rooted in a tension between expectations - those towards himself and towards his paying audience. It is a tension between the private and the public, the private epitomised in music of a "highbrow" kind (whatever its intended audience), and the public epitomised in his theatre music. Via a comparison of works private (especially songs from Harmonia Sacra) and public (mainly theatre songs), the paper will define the thinking and practice that differentiates the two spheres. It will also suggest that the private sphere was so deeply embedded that Purcell's reputation inevitably rests on a small number of works. In that respect too, he makes a revealing comparison with the other composers in this conference. Maria Teresa Arfini Milan and Aosta University Music as Autobiography: Mendelssohn between Beethoven and Schumann There are some compositions where Mendelssohn shows actually autobiographical traits. -

A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: an Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 1992 A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Utz, Hans (1992) "A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 27: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hans UIZ A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture The book Voyage en Ecosse et aux Iles Hebrides by Louis-Albert Necker de Saussure of Geneva is the basis for my report.! While he was studying in Edinburgh he began his private "discovery of Scotland" by recalling the links existing between the foreign country and his own: on one side, the Calvinist church and mentality had been imported from Geneva, while on the other, the topographic alternation between high mountains and low hills invited comparison with Switzerland. Necker's interest in geology first incited his second step in discovery, the exploration of the Highlands and Islands. Presently his ethnological curiosity was aroused to investigate a people who had been isolated for many centuries and who, after the abortive Jacobite Re bellion of 1745-1746, were confronted with the advanced civilization of Lowland Scotland, and of dominant England.