German Virtuosity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schubert's!Voice!In!The!Symphonies!

! ! ! ! A!Search!for!Schubert’s!Voice!in!the!Symphonies! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Camille!Anne!Ramos9Klee! ! Submitted!to!the!Department!of!Music!of!Amherst!College!in!partial!fulfillment! of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of!Bachelor!of!Arts!with!honors! ! Faculty!Advisor:!Klara!Moricz! April!16,!2012! ! ! ! ! ! In!Memory!of!Walter!“Doc”!Daniel!Marino!(191291999),! for!sharing!your!love!of!music!with!me!in!my!early!years!and!always!treating!me!like! one!of!your!own!grandchildren! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! Introduction! Schubert,!Beethoven,!and!the!World!of!the!Sonata!! 2! ! ! ! Chapter!One! Student!Works! 10! ! ! ! Chapter!Two! The!Transitional!Symphonies! 37! ! ! ! Chapter!Three! Mature!Works! 63! ! ! ! Bibliography! 87! ! ! Acknowledgements! ! ! First!and!foremost!I!would!like!to!eXpress!my!immense!gratitude!to!my!advisor,! Klara!Moricz.!This!thesis!would!not!have!been!possible!without!your!patience!and! careful!guidance.!Your!support!has!allowed!me!to!become!a!better!writer,!and!I!am! forever!grateful.! To!the!professors!and!instructors!I!have!studied!with!during!my!years!at! Amherst:!Alison!Hale,!Graham!Hunt,!Jenny!Kallick,!Karen!Rosenak,!David!Schneider,! Mark!Swanson,!and!Eric!Wubbels.!The!lessons!I!have!learned!from!all!of!you!have! helped!shape!this!thesis.!Thank!you!for!giving!me!a!thorough!music!education!in!my! four!years!here!at!Amherst.! To!the!rest!of!the!Music!Department:!Thank!you!for!creating!a!warm,!open! environment!in!which!I!have!grown!as!both!a!student!and!musician.!! To!the!staff!of!the!Music!Library!at!the!University!of!Minnesota:!Thank!you!for! -

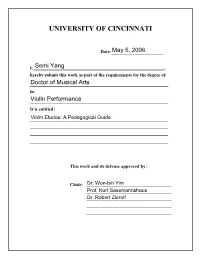

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

T H O M a N E R C H

Thomanerchor LeIPZIG DerThomaner chor Der Thomaner chor ts n te on C F o able T Ta b l e o f c o n T e n T s Greeting from “Thomaskantor” Biller (Cantor of the St Thomas Boys Choir) ......................... 04 The “Thomanerchor Leipzig” St Thomas Boys Choir Now Performing: The Thomanerchor Leipzig ............................................................................. 06 Musical Presence in Historical Places ........................................................................................ 07 The Thomaner: Choir and School, a Tradition of Unity for 800 Years .......................................... 08 The Alumnat – a World of Its Own .............................................................................................. 09 “Keyboard Polisher”, or Responsibility in Detail ........................................................................ 10 “Once a Thomaner, always a Thomaner” ................................................................................... 11 Soli Deo Gloria .......................................................................................................................... 12 Everyday Life in the Choir: Singing Is “Only” a Part ................................................................... 13 A Brief History of the St Thomas Boys Choir ............................................................................... 14 Leisure Time Always on the Move .................................................................................................................. 16 ... By the Way -

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (Geb

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (geb. Hamburg, 3. Februar 1809 — gest. Leipzig, 4. November 1847)Die Die Loreley Op. 98 Vorwort Mendelssohn spielte wahrlich keine bedeutsame Rolle bei der Weiterentwicklung der Oper. Trotzdem wurde die Frage seines Beitrags zum Genre in der Zeit nach seinem Tod leidenschaftlich diskutiert. Einige Kritiker — am berüchtigtsten Richard Wagner— hielten den Komponisten für schlichtweg unfähig, solche Werke zu schreiben. Für andere dagegen war das Oratorium Elijah ein Neustart, das den Weg bereitete — wie ein zeitgenössischer Kritiker bemerkte — für ein neues Stadium der dramatischen Musik, das Die Loreley einleiten sollte. Aus dieser Sicht war Mendelssohns frühzeitiger Tod ein doppelter Schlag: gerade im Begriff, einen substantiellen Beitrag zur Oper zu leisten, der mit anderen Ansätzen gut hätte konkurrieren können, blieb seine Verheißung jedoch unerfüllt. Daß Mendelssohn als Enddreißiger die Welt der Oper noch nicht hatte erobern können, ist kennzeichnend für seine vielschichtige Einstellung diesem Genre gegenüber. Dramatische Musik hatte ihn vom Beginn seiner kreativen Unternehmungen beschäftigt: im Alter zwischen 11 und 15 Jahren schrieb er vier komische Opern für hausmusikalische Aufführungen; Die Soldatenliebschaft (1820), Die beiden Pädagogen (1821), Die wandernden Komödianten (1821) and Die beiden Neffen, oder Der Onkel aus Boston 1822-23). Diese Werke rührten aber nicht von seinem Kompositionsunterricht bei dem Berliner Komponisten, Dirigenten und Pädagogen Carl Friedrich Zelter her, sondern sie entsprangen Mendelssohns eigener kreativer Schaffenslust. Das letztere Werk — Der Onkel aus Boston — ist charakteristisch für Mendelssohns altersgemäße Entwicklung: nach der ersten Generalprobe des Werkes am fünfzehnten Geburtstag des Komponisten bemerkte Zelter darin genügend Fortschritt und Originalität, um Mendelssohn "den Gesellenbrief…im Namen Mozarts, im Namen Haydns und im Namen des Altmeisters Bach" zu verleihen. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Einleitung Zu SON

XII Einleitung Von den in dem Band „Weitere Orchesterwerke“1 vorgeleg- Wohnort vorgelegt.4 Doberan war 1793 nach südenglischem ten Kompositionen Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdys bildet die Vorbild als erstes Ostseebad von Friedrich Franz I. ( 1756– 1837) Ouver türe für Harmoniemusik C-Dur op. 24 MWV P 1 inso- eingerichtet worden. Der kunstbeflissene Monarch, seit 1785 fern eine Besonderheit, als sie in mehreren Fassungen existiert Herzog zu Mecklenburg und seit 1815 Großherzog von Meck- und deshalb als einzige Komposition dieser Werkgruppe für lenburg-Schwerin, nutzte Doberan als Sommerresidenz.5 Er den Inhalt des vorliegenden Bandes in Frage kam. Es handelt unterhielt in Ludwigslust eine Hofkapelle, deren Ruf weit über sich um eine zu Lebzeiten Mendelssohns unveröffentlichte Fas- den unmittelbaren Wirkungsort ausstrahlte.6 Einige Musiker sung für elf Blasinstrumente von 1826 sowie um zwei Arrange- versahen ihren Dienst in den Sommermonaten in Doberan, ments für Klavier zu vier Händen, die 1838 im Zusammenhang also an jenem Ort nahe der Ostsee, den Mendelssohn als „ein mit der Hauptfassung für 23 Blasinstrumente und Janitscha- hübsches Dorf im Sande“7 bezeichnete. reninstrumente entstanden. Die herausgehobene Stellung wird Durch insgesamt zehn erhaltene Briefe, die zwischen 3. und zudem durch eine beachtliche Quellenvielfalt, etliche mit der 31. Juli 1824 von Doberan nach Berlin geschickt wurden, ist Entstehung zusammenhängende ungelöste Fragen sowie durch die Nachwelt detailliert über die dortigen Ereignisse und die den Umstand unterstrichen, dass die Ouvertüre in der erweiter- Eindrücke der verreisten Mendelssohns informiert.8 Drei Tage ten Bläserfassung als einziges Stück dieses Werkbestandes vom nach Ankunft resümierte der Fünfzehnjährige humorvoll: „Wir selbstkritischen Komponisten für wert befunden wurde, veröf- haben hier gräulich viel zu thun. -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Franz Schubert Wolfgang

STIFTUNG MOZARTEUM SALZBURG WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 FRANZ SCHUBERT SYMPHONY NO. 5 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART PIANO CONCERTO NO. 23 ANDRÁS SCHIFF CAPPELLA ANDREA BARCA WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Vienna - once the music hub of Europe - attracted all the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 greatest composers of its day, among them Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart. This concert given by András Schiff and FRANZ SCHUBERT the Capella Andrea Barca during the Salzburg Mozart Week Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, D 485 brings together three works by these great composers, which WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART each of them created early in life at the start of an impressive Piano Concerto No. 23 in E flat major, KV 482 Viennese career. The programme opens with Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto: Piano & Conductor András Schiff “Sensitively supported by the rich and supple tone of the strings, Orchestra Cappella Andrea Barca Schiff’s pianistic virtuosity explores the length and breadth of Beethoven’s early work, from the opulent to the playful, with a Produced by idagio.production palpable delight rarely found in such measure in a pianist”, was Video Director Oliver Becker the admiring verdict of the Salzburg press. Length: approx. 100' As in his opening piece, Schiff again succeeded in Schubert’s Shot in HDTV 1080/50i symphony “from the first note to the last in creating a sound Cat. no. A 045 50045 0000 world that flooded the mind’s eye with images” Drehpunkt( Kultur). A co-production of The climax of the concert was the Mozart piano concerto. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

Chapter 5 – the Enlightenment and the American Revolution I. Philosophy in the Age of Reason (5-1) A

Chapter 5 – The Enlightenment and the American Revolution I. Philosophy in the Age of Reason (5-1) A. Scientific Revolution Sparks the Enlightenment 1. Natural Law: Rules or discoveries made by reason B. Hobbes and Lock Have Conflicting Views 1. Hobbes Believes in Powerful Government a. Thomas Hobbes distrusts humans (cruel-greedy-selfish) and favors strong government to keep order b. Promotes social contract—gaining order by giving up freedoms to government c. Outlined his ideas in his work called Leviathan (1651) 2. Locke Advocates Natural Rights a. Philosopher John Locke believed people were good and had natural rights—right to life, liberty, and property b. In his Two Treatises of Government, Lock argued that government’s obligation is to protect people’s natural rights and not take advantage of their position in power C. The Philosophes 1. Philosophes: enlightenment thinkers that believed that the use of reason could lead to reforms of government, law, and society 2. Montesquieu Advances the Idea of Separation of Powers a. Montesquieu—had sharp criticism of absolute monarchy and admired Britain for dividing the government into three branches b. The Spirit of the Laws—outlined his belief in the separation of powers (legislative, executive, and judicial branches) to check each other to stop one branch from gaining too much power 3. Voltaire Defends Freedom of Thought a. Voltaire—most famous of the philosophe who published many works arguing for tolerance and reason—believed in the freedom of religions and speech b. He spoke out against the French government and Catholic Church— makes powerful enemies and is imprisoned twice for his views 4. -

Dissertation FINAL 5 22

ABSTRACT Title: BEETHOVEN’S VIOLINISTS: THE INFLUENCE OF CLEMENT, VIOTTI, AND THE FRENCH SCHOOL ON BEETHOVEN’S VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS Jamie M Chimchirian, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Dr. James Stern Department of Music Over the course of his career, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) admired and befriended many violin virtuosos. In addition to being renowned performers, many of these virtuosos were prolific composers in their own right. Through their own compositions, interpretive style and new technical contributions, they inspired some of Beethoven’s most beloved violin works. This dissertation places a selection of Beethoven’s violin compositions in historical and stylistic context through an examination of related compositions by Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824), Pierre Rode (1774–1830) and Franz Clement (1780–1842). The works of these violin virtuosos have been presented along with those of Beethoven in a three-part recital series designed to reveal the compositional, technical and artistic influences of each virtuoso. Viotti’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major and Rode’s Violin Concerto No. 10 in B minor serve as examples from the French violin concerto genre, and demonstrate compositional and stylistic idioms that affected Beethoven’s own compositions. Through their official dedications, Beethoven’s last two violin sonatas, the Op. 47, or Kreutzer, in A major, dedicated to Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Op. 96 in G major, dedicated to Pierre Rode, show the composer’s reverence for these great artistic personalities. Beethoven originally dedicated his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, to Franz Clement. This work displays striking similarities to Clement’s own Violin Concerto in D major, which suggests that the two men had a close working relationship and great respect for one another.