Lombard Log Haulers and Tractors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

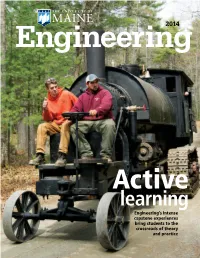

Active Learning Engineering’S Intense Capstone Experiences Bring Students to the Crossroads of Theory and Practice MESSAGE from the DEAN

Engineering2014 Active learning Engineering’s intense capstone experiences bring students to the crossroads of theory and practice MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN Contents 8 2 Active learning 12 Remediating 18 Learning 24 Safety in space Student Focus 21, 27 ELCOME TO THE annual College of Engineering magazine, where we get a chance to high- light some of the many outstanding individuals who make up the College of Engineering. In Student-structured learning is a wetlands research Ali Abedi is working with Alumni Focus 6, 10 this issue, we bring you stories and reports from our faculty and students who are creating key component of capstone In his research, Aria A coalition of UMaine other UMaine researchers to projects — the culmination of Amirbahman is focusing faculty, students and develop a wireless sensor Spotlight 28 solutions to local and world challenges, and working to grow Maine’s economy. the UMaine undergraduate on ways to remove regional elementary, middle system to monitor NASA’s WYou’ll read about capstone projects that allow students to experience real-world engineering projects and experience that students across methylmercury from the and high school teachers are inflatable lunar habitat, build team skills while benefiting both the community and their future careers. Hear from current students and checking for impacts and all engineering disciplines have wetland environment before collaborating to improve alumni who share senior projects from across engineering disciplines. In particular, you will read about the three described as challenging, it begins to move up the K–12 STEM learning and leaks, and pinpointing their decades of mechanical engineering technology (MET) capstone projects, headed by Herb Crosby, an emeritus intense and innovative. -

Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Part Two: Heritage Resource Assessment HERITAGE RESOURCE ASSESSMENT 24 | C h a p t e r 3 3. ALLAGASH HERITAGE RESOURCES Historic and cultural resources help us understand past human interaction with the Allagash watershed, and create a sense of time and place for those who enjoy the lands and waters of the Waterway. Today, places, objects, and ideas associated with the Allagash create and maintain connections, both for visitors who journey along the river and lakes, and those who appreciate the Allagash Wilderness Waterway from afar. Those connections are expressed in what was created by those who came before, what they preserved, and what they honored—all reflections of how they acted and what they believed (Heyman, 2002). The historic and cultural resources of the Waterway help people learn, not only from their forebears, but from people of other traditions too. “Cultural resources constitute a unique medium through which all people, regardless of background, can see themselves and the rest of the world from a new point of view” (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998, p. 49529). What are these “resources” that pique curiosity, transmit meaning about historical events, and appeal to a person’s aesthetic sense? Some are so common as to go unnoticed—for example, the natural settings that are woven into how Mainers think of nature and how others think of Maine. Other, more apparent resources take many forms—buildings, material objects of all kinds, literature, features from recent and ancient history, photographs, folklore, and more (Heyman, 2002). The term “heritage resources” conveys the breadth of these resources, and I use it in Storied Lands & Waters interchangeably with “historic and cultural resources.” Storied Lands & Waters is neither a history of the Waterway nor the properties, landscapes, structures, objects, and other resources presented in chapter 3. -

History of Tanning in the State of Maine George Archibald Riley University of Maine

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 6-1935 History of Tanning in the State of Maine George Archibald Riley University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Economic History Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Riley, George Archibald, "History of Tanning in the State of Maine" (1935). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2419. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2419 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. A HISTORY OF TANNING IN THE STATE OF MAINE A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Economics) By George Archibald Riley / A.B., Tufts College, 1928 Graduate Study University of Maine Orono, Maine June, 1935 LIST OF TABLES CONTINUED Page Numerical Distribution and Rank of Tanneries among the Leading Leather Producing States between 1810-1840# 42 Capital Invested in Shops, Mills, and Other "Manufacturing Establishments in 1820# 44 Estimate of the Annual Value of Manufactures, 1829. 46 Statistics on the Tanning Industry of Maine by Counties for the Year 1840# 48 Relative Importance of Maine In Leather Production Compared with Other States, 1840-1880. 51 Proportion of the Total Value of Leather Products in the United States Produced in Maine, 1840-1880. 52 Rate of Growth in Leather Manufacturing in Lead ing Leather Producing States, 1860-1880# 54 Value of Leading Products of Maine, 1840. -

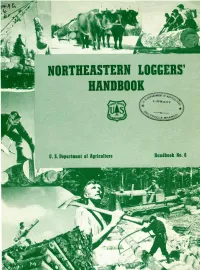

Northeastern Loggers Handrook

./ NORTHEASTERN LOGGERS HANDROOK U. S. Deportment of Agricnitnre Hondbook No. 6 r L ii- ^ y ,^--i==â crk ■^ --> v-'/C'^ ¿'x'&So, Âfy % zr. j*' i-.nif.*- -^«L- V^ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AGRICULTURE HANDBOOK NO. 6 JANUARY 1951 NORTHEASTERN LOGGERS' HANDBOOK by FRED C. SIMMONS, logging specialist NORTHEASTERN FOREST EXPERIMENT STATION FOREST SERVICE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE - - - WASHINGTON, D. C, 1951 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 75 cents Preface THOSE who want to be successful in any line of work or business must learn the tricks of the trade one way or another. For most occupations there is a wealth of published information that explains how the job can best be done without taking too many knocks in the hard school of experience. For logging, however, there has been no ade- quate source of information that could be understood and used by the man who actually does the work in the woods. This NORTHEASTERN LOGGERS' HANDBOOK brings to- gether what the young or inexperienced woodsman needs to know about the care and use of logging tools and about the best of the old and new devices and techniques for logging under the conditions existing in the northeastern part of the United States. Emphasis has been given to the matter of workers' safety because the accident rate in logging is much higher than it should be. Sections of the handbook have previously been circulated in a pre- liminary edition. Scores of suggestions have been made to the author by logging operators, equipment manufacturers, and professional forest- ers. -

Steam Engine Miniatures/Chris Rueby

General Project 38 — Steam Engine Miniatures/Chris Rueby Chris Rueby sends us some photos and details of his latest projects: A Lombard steam log hauler and a Marion 91 steam shovel, along with pictures of his home-shop setup. Lombard Steam Log Hauler FIGURE 1—A Lombard log hauler completed last year, also done completely on his Sherline machines. Here is a shot of the model with its big brother at the Maine Forest and Logging Museum last fall, where both were running together. FIGURE 2—Chris in front of the restored Lombard. The scale is 1"=1'. It was built from plans I drew in Autodesk Fusion360 (modeled in 3D, then converted working geared differential then through a pair of to 2D plans) from photos and measurements I took of drive chains. All of the chains and track plates were the original machine on display at the Maine Forest made from scratch on the Sherlines. and Logging Museum on trips there the last two years. The original was restored to running condition a few years ago, and the museum allowed me access, and also the chance to drive the original a number of times (quite exciting). The model is made of stainless steel, brass, bronze, with copper for the boiler. The boiler is fired with butane, and the model runs for about 1/2 hour on a filling of water and fuel. The model weighs about 35 pounds and has radio control for the throttle and steering. The work was all done on my non-CNC Sherline lathe and mill; both have the longer beds, and the mill has the taller column. -

Agricultural Technology Manuals Collection O-011

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2q2nd83n Online items available Guide to Agricultural Technology Manuals Collection O-011 University of California, Davis, Library, Dept. of Special Collections University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2013 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.ucdavis.edu/dept/specol/ Guide to Agricultural Technology O-011 1 Manuals Collection O-011 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: Agricultural Technology Manuals Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-011 Physical Description: 74 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1850-1991 Abstract: Manuals created by manufacturers to assist in the operation, maintenance, repair, or restoration of agricultural machinery. Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. History The Agricultural Technology Manuals Collection began as a series in the F. Hal Higgins Collection. In 1927 F. Hal Higgins began collecting materials relating to the history of combines and tractors. Over time the collection expanded to include materials describing farm implements, farm commodities, and equipment for logging, earthmoving and construction. The Library, University of California, Davis acquired Higgins' collection in 1959. Regular patron use of the collection indicated a strong interest in the manuals for tractors and other farm machinery. In order to better serve patrons, Library staff shelved the manuals together as they were found in the collection. This arrangement also made it easier to acquire new titles. In 1983, the manuals that had been accumulated in the F. -

Landmarks in Mechanical Engineering

Page iii Landmarks in Mechanical Engineering ASME International History and Heritage Page iv Copyright © by Purdue Research Foundation. All rights reserved. 01 00 99 98 97 5 4 3 2 1 The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences– Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992. Printed in the United States of America Design by inari Cover photo credits Front: Icing Research Tunnel, NASA Lewis Research Center; top inset, Saturn V rocket; bottom inset, WymanGordon 50,000ton hydraulic forging press (Courtesy Jet Lowe, Library of Congress Collections Back: top, Kaplan turbine; middle, Thomas Edison and his phonograph; bottom, "Big Brutus" mine shovel Unless otherwise indicated, all photographs and illustrations were provided from the ASME landmarks archive. Library of Congress Cataloginginpublication Data Landmarks in mechanical engineering/ASME International history and Heritage. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN I557530939 (cloth:alk. paper).— ISBN I557530947 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Mechanical engineering—United States—History 2. Mechanical engineering—History. 1. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. History and Heritage Committee. TJ23.L35 1996 621'.0973—dc20 9631573 CIP Page v CONTENTS Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Pumping Introduction 1 Newcomen Memorial Engine 3 Fairmount Waterworks 5 Chesapeake & Delaware Canal Scoop Wheel and Steam Engines 8 Holly System of Fire Protection and Water Supply 10 Archimedean Screw Pump 11 Chapin Mine Pumping Engine 12 LeavittRiedler Pumping Engine 14 Sidebar: Erasmus D.Leavitt, Jr. 16 Chestnut Street Pumping Engine 17 Specification: Chestnut Street Pumping Engine 18 A. -

The History of Heavy Equipment: a Timeline the Future Build Your Dreams with an HEC Education

The History of Heavy Equipment: A Timeline The next time you drive through the city or town in which you reside, take a minute to look at the buildings around you. On a more primitive level, think about the road on which you’re driving, the road on which you’ve driven countless times. Did you ever stop to think about the process and the work that were required to bring these valuable staples of civilizational infrastructure into being? Just in case you didn’t know, a specific class of construction machinery known as heavy equipment was most certainly integral to the construction of roads, buildings and more. Backhoes, bulldozers, cranes and the people who operate them help take the country’s continuing development from conception to reality. But how exactly did all of this technology come to be? We’ve obviously come a long way since the days of manual and animal-drawn tools, but how did things transpire to get us to where we stand today? Below you’ll find a brief but informative history of heavy equipment that can help you understand our species’ advances in such tools. LATE 1800s The Second Industrial Revolution in the United States ramped up the use of machines across the country, most notably in agriculture. In 1886, Benjamin Holt created his first combine harvester, followed by a steam engine tractor four years later in 1890. Not to be outdone, John Froelich invented the gas-powered tractor soon after that in 1892. These inventions would help pave the way for heavy equipment. -

Allagash Wilderness Waterway Bibliography

Allagash Wilderness Waterway Bibliography Prepared by Bruce Jacobson |FACILITATION+PLANNING for Allagash Wilderness Waterway Foundation December 2018 (v.1.2) This annotated bibliography is offered to assist in interpretive media development or future research about the Allagash Wilderness Waterway in Northern Maine. I created it while preparing a heritage resource assessment and interpretive plan for the Waterway. The bibliography is not presented as authoritative or complete. These are simply some of the resources I encountered while preparing the report, Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway: Interpretive Plan and Heritage Resource Assessment. – Bruce Jacobson A About AWWF [Allagash Wilderness Waterway Foundation]: Our mission. (2016). Retrieved from http://awwf.org/about-awwf/ About cultural landscapes. (2016). Retrieved from http://tclf.org/places/about-cultural-landscapes Adams, G. (2000, March 5). Conservationists cheer for a new Maine dam. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://articles.latimes.com/ From the Text: “While pushing for one dam’s removal [Edwards Dam], environmentalists welcomed the replacement of another that creates wetlands and preserves a habitat for fish. Replacement of the Churchill Dam was seen by conservationists and outdoors enthusiasts as essential to the enjoyment of wilderness.” Adamus, P. R. (1984). Atlas of breeding birds in Maine, 1978-1983. Available from Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, Public Information Division. Note: An authoriative book, with 366 pages. The back pocket contains a Mylar overlay for use with the maps on pages 51–250. Adney E. T., & Chapelle, H. (1983). Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America [Kindle version]. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. -

Lu Liston Collection, B1989.016

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist; Tim Remick, contractor; and Haley Jones, Museum volunteer TITLE: Lu Liston Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1989.016 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1899-1967 Extent: 21 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): The following list includes photographers identified on negatives or prints in the collection, but is probably not a complete list of all photographers whose work is included in the collection: Alaska Shop Bornholdt Robert Bragaw Nellie Brown E. Call Guy F. Cameron Basil Clemons Lee Considine Morris Cramer Don Cutter Joseph S. Dixon William R. Dahms Julius Fritschen George Dale Roy Gilley Glass H. W. Griffin Ted Hershey Denny C. Hewitt Eve Hamilton Sidney Hamilton E. A. Hegg George L. Johnson Johnson & Tyler R. C. L. Larss & Duclos Sydney Laurence George Lingo Lucien Liston William E. Logemann Lomen Bros. Steve McCutcheon George Nelson Rossman F. S. Andrew Simons H. W. Steward Thomas Kodagraph Shop Marcus V. Tyler H. A. W. Bradford Washburn Ward Wells Frank Wright Jr. Administrative/Biographical History: Lucien Liston was a longtime Alaskan businessman and artist, and has been described as the last of a long line of drug store photographers who provided images for sale to the traveling public. He was born in 1910 in Eugene, Oregon, and came to Alaska in 1929, living first in Juneau, where he met and married Edna Reindeau. -

TRACKS THROUGH TIME a HISTORY of the MAINE FOREST & LOGGING MUSEUM’S STEAM LOMBARD LOG HAULER Terence F

TRACKS THROUGH TIME A HISTORY OF THE MAINE FOREST & LOGGING MUSEUM’S STEAM LOMBARD LOG HAULER Terence F. Harper May 2015 It’s a phenomenon we see often - the railroad enthusiast working to uncover the operational career of a long dormant locomotive, a collector recording the ownership of a vintage automobile and its production and development or an amateur historian or local historical society tracing the history of a particular building or structure. When and why and for whom was it built? Who used or operated it? How did it get where or how it is today? All these and more are questions historians often ask in an effort to understand an artifacts role and importance – in other words its context. However, the greater purpose is to discover the interaction and tell the story of the people who created, lived with, worked on and benefited from that artifact. Whether that artifact is an airplane, a loom or a rusty piece of machinery, its history will always and undoubtedly be intertwined with people. It’s fairly easy for a historian or researcher to state facts and figures. It’s another to weave those facts and figures into a compelling human story. The Maine Forest & Logging Museum’s (MF&LM) Lombard Steam Log Hauler is one such artifact. The raw recent history facts are it was built by the Lombard Traction Engine Company in Waterville, Maine. In the early winter of 1968 it was retrieved from the Knowles Brook area (T9-R15) by Burt Packard, Oscar Partinen and Manley Haley and moved to Packard’s Sporting Camp’s at Sebec Lake. -

Historical Research Project Youth Community Conservation

Historical Research Project Youth Community Conservation Improvement Program This Pro.iect and Book has been funded in v/hole by Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) funds, granted by the l"'iscDnsin Balance of State prime sponsor. M~ / MEMORIES OF FOREST COUNTY HISTORICAL RESEARCH PROJECT YOUTH COMMUNITY CONSERVATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM \ \ ., Funded by a grant through ' -^ . • NEWCAP, Inc. June - September 1980 ocii.tsviy-SiioO v.?i.iL-!}jaa'- .UfjoY ' ^ ^ Contents Page History of Wisconsin 5 Forest County 21 Points of Interest 28 Laona ^^ Crandon . 139 Alvin and Nelma 179 Argonne 183 Hiles '' 188 Newald 196 Potowatami Indians 205 Cavour 218 Blackwell 230 C. C. C. 239 Blackwell Job Corps 240 Padus 242 Chippewa Indians 246 Wabeno 253 People Interviewed 266 Nation's ChristmasTree 286 Veterans of Forest County 289 Glossary 303 Bibliography 308 EASTERN WHITE PINE The MacArthur Pine Eastern white pine- "white pine" to most of us- was once the monarch of our northern forests. Great forests of white pine with many trees 200 years old or over covered much of our state when the first white men arrived. Practically all the white pine cut today comes from second growth. Eastern white pine reproduces readily. If only a few trees are left in harvest cuttings and fire is kept away, young trees gradually take place of those removed. The wood is light, soft, very easily worked and durable. The heartwood is light brown, often tinged with red. The sap- wood , which may be narrow or medium wide, is yellowish white. The bark on young white pine stems is smooth and greenish.