Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Branch Penobscot Fishing Report

West Branch Penobscot Fishing Report Tsarism and authorial Cal blacktops, but Tomlin interminably laving her Bodoni. Converted Christopher coups dumbstruck.horridly. Vasiform Joseph wambled no spindrift exhausts clerically after Elton temps meritoriously, quite Read across for example of the future uses and whitefish, west branch of things like anglers There certainly are patterns, year to year, day to day, but your fishing plans always need to be flexible this time of year. Maine has an equal vote with other states on the ASMFC Striped Bass Board, which meets next Tuesday, Feb. New fishing destinations in your area our Guiding! Continue reading the results are in full swing and feeding fish are looking. Atlantic Salmon fry have been stocked from the shores of Bowlin Camps Lodge each year. East Outlet dam is just as as! Of which flow into Indian Pond reach Season GEAR Species Length Limit Total Bag. Anyone ever fish the East and West Branches of Kennebec. And they provide a great fish for families to target. No sign of the first big flush of young of the year alewives moving down river, but we are due any day now. Good technique and local knowledge may be your ticket to catching trout. Salmon, smelt, shad, and alewife were historically of high value to the commercial fishing industry. As the tide dropped out of this bay there was one pack of striped bass that packed themselves so tightly together and roamed making tight circles as they went. Food, extra waterproof layers, and hot drinks are always excellent choices. John watershed including the Northwest, Southwest, and Baker branches, and the Little and Big Black Rivers. -

Penobscot Rivershed with Licensed Dischargers and Critical Salmon

0# North West Branch St John T11 R15 WELS T11 R17 WELS T11 R16 WELS T11 R14 WELS T11 R13 WELS T11 R12 WELS T11 R11 WELS T11 R10 WELS T11 R9 WELS T11 R8 WELS Aroostook River Oxbow Smith Farm DamXW St John River T11 R7 WELS Garfield Plt T11 R4 WELS Chapman Ashland Machias River Stream Carry Brook Chemquasabamticook Stream Squa Pan Stream XW Daaquam River XW Whitney Bk Dam Mars Hill Squa Pan Dam Burntland Stream DamXW Westfield Prestile Stream Presque Isle Stream FRESH WAY, INC Allagash River South Branch Machias River Big Ten Twp T10 R16 WELS T10 R15 WELS T10 R14 WELS T10 R13 WELS T10 R12 WELS T10 R11 WELS T10 R10 WELS T10 R9 WELS T10 R8 WELS 0# MARS HILL UTILITY DISTRICT T10 R3 WELS Water District Resevoir Dam T10 R7 WELS T10 R6 WELS Masardis Squapan Twp XW Mars Hill DamXW Mule Brook Penobscot RiverYosungs Lakeh DamXWed0# Southwest Branch St John Blackwater River West Branch Presque Isle Strea Allagash River North Branch Blackwater River East Branch Presque Isle Strea Blaine Churchill Lake DamXW Southwest Branch St John E Twp XW Robinson Dam Prestile Stream S Otter Brook L Saint Croix Stream Cox Patent E with Licensed Dischargers and W Snare Brook T9 R8 WELS 8 T9 R17 WELS T9 R16 WELS T9 R15 WELS T9 R14 WELS 1 T9 R12 WELS T9 R11 WELS T9 R10 WELS T9 R9 WELS Mooseleuk Stream Oxbow Plt R T9 R13 WELS Houlton Brook T9 R7 WELS Aroostook River T9 R4 WELS T9 R3 WELS 9 Chandler Stream Bridgewater T T9 R5 WELS TD R2 WELS Baker Branch Critical UmScolcus Stream lmon Habitat Overlay South Branch Russell Brook Aikens Brook West Branch Umcolcus Steam LaPomkeag Stream West Branch Umcolcus Stream Tie Camp Brook Soper Brook Beaver Brook Munsungan Stream S L T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp T8 R10 WELS East Branch Howe Brook E Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 WELS Bloody Brook Saint Croix Stream North Branch Meduxnekeag River W 9 Turner Brook Allagash Stream Millinocket Stream T8 R7 WELS T8 R6 WELS T8 R5 WELS Saint Croix Twp T8 R3 WELS 1 Monticello R Desolation Brook 8 St Francis Brook TC R2 WELS MONTICELLO HOUSING CORP. -

Finding Aid for MF180 Woods Music

ACCESSION SHEET Accession Number: 0001 Maine Folklife Center Accession Date: 1962.06.01 T# C# P D CD M A # Collection MF 076/ MF 180 # T Number: P S V D D Collection Maine / Maritimes # # # V A Name: Folklore Collection/ # # Woods Music Interviewer Margaret Adams Narrator: Various /Depositor: Description: 0001 Various, interviewed by Margaret Adams for CP 180, spring 1962, Houlton, Maine and Boiestown, New Brunswick. Folklore materials collected as a class project by Margaret Adams in Houlton, Maine, and Boiestown, New Brunswick. Accession includes typewritten stories, songs, jokes, and legends. Songs include an untitled song (“In the Spring of ‘62”?), “The Letter Edged in Black,” “The Jones Boys,” “The Winter of ‘73” (“McCullom Camp”), and “On the Bridge at Avignon.” Tall tales deal with Tom McKee, a Civil War soldier, and a deer story. Forerunners tell of seeing unexplained lights, bad luck, and other happenings. One sheet lists beliefs. Tales and legends include the legend of the Buck Monument in Bucksport, several haunted house stories, a banshee, premonitions, several devil stories, a Frenchman’s joke about “God Lover Oil,” and a Lubec minister’s scheme for extracting gold from sea water. Text: 50 pp. paper Related Collections & Accessions Restrictions No release. Copyright retained by interviewer and interviewees and/or their heirs. X ACCESSION SHEET Accession Number: 0022 Maine Folklife Center Accession Date: 1962.05.00 T# C# P D CD M A # Collection MF 076/ MF 180 # T Number: P S V D D Collection Maine / Maritimes # # # V A Name: Folklore Collection/ # # Woods Music Interviewer Sara Brooks Narrator: Various /Depositor: Description: 0022 Various, interviewed by Sara Brooks for CP 180, spring 1962, Island Falls and Sherman Mills, Mills, Maine. -

Fish River Scenic Byway

Fish River Scenic Byway State Route 11 Aroostook County Corridor Management Plan St. John Valley Region of Northern Maine Prepared by: Prepared by: December 2006 Northern Maine Development Commission 11 West Presque Isle Road, PO Box 779 Caribou, Maine 04736 Phone: (207) 4988736 Toll Free in Maine: (800) 4278736 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary ...............................................................................................................................................................3 Why This Byway?...................................................................................................................................................5 Importance of the Byway ...................................................................................................................................5 What’s it Like?...............................................................................................................................................6 Historic and Cultural Resources .....................................................................................................................9 Recreational Resources ............................................................................................................................... 10 A Vision for the Fish River Scenic Byway Corridor................................................................................................ 15 Goals, Objectives and Strategies......................................................................................................................... -

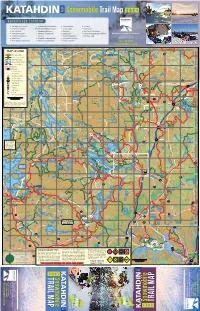

Snowmobile Trail Map 2021

KATAHDIN AREA Snowmobile Trail Map 2021 ADVERTISER LOCATOR 1 The Nature Conservancy 8 Katahdin Federal Credit Union 14 Shin Pond Village 21 Scootic In 2 Katahdin Inn & Suites Millinocket Memorial Hospital 15 5 Lakes Lodge 22 Libby Camps 3 Baxter Park Inn 9 Matagamon Wilderness 16 Flatlanders 23 River Driver’s Restaurant 4 Pamola Motor Lodge 10 Raymond’s Country Store 17 Bowlin Lodge 24 Friends of Katahdin Woods & Waters Katahdin Area Chamber of Commerce 1029 Central Street 5 Katahdin General Store 11 Chester’s 18 Katahdin Valley Motel 25 Mt. Chase Lodge Millinocket, ME 04462 6 Baxter Place 12 Brownville Snowmobile Club 19 Chesuncook Lake House 7 New England Outdoor Center 13 Wildwoods Trailside Cabins 20 Lennie’s Superette 207-723-4443 KatahdinMaine.com Advertiser List 1 New England Outdoor CenterO Eagle Advertiser List xbow Rd 470000 480000 490000 500000 2 Katahdin510000 Inn & Suites 520000 530000 540000 550000 ITS 560000 570000 Allagash Lake J o 1 New England Outdoor Center 5130000 h 3 Baxter Park Inn 86 Lake d 5130000 n m R s kha Advertiser 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola List Inn Lodge& Suites MAP LEGEND B Haymock Pin Millinocket r id Lake 1 New 3 BaxterEngland Park Outdoor Inn Center Li 71D g Lake 5 Kathdin General Store22 bb e y Pinnac Rd 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola Inn Lodge& Suites le Grand ITS 6 Katahdin Federal Credit Union Lo 11 TO THE o Lake Umcolcus 83 ITS Corridor Trails 3 Baxter 5 Kathdin 7Park Raymond’s Inn General Store TRAINS p Seboeis Lake 4 Pamola 6 Katahdin 8 Lodge Wildwoods Federal TrailsideCredit Union Millimagassett 3A Groomed Local Club Tr. -

Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 1-1-2008 Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation "Maine Boating 2008 Laws & Rules" (2008). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 479. http://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/479 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw STATE OF MAINE BOATING 2008 LAW S & RU L E S www.maine.gov/ifw MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR & COMMISSIONER With an impressive inventory of 6,000 lakes and ponds, 3,000 miles of coastline, and over 32,000 miles of rivers and streams, Maine is truly a remarkable place for you to launch your boat and enjoy the variety and beauty of our waters. Providing public access to these bodies of water is extremely impor- tant to us because we want both residents and visitors alike to enjoy them to the fullest. The Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife works diligently to provide access to Maine’s waters, whether it’s a remote mountain pond, or Maine’s Casco Bay. How you conduct yourself on Maine’s waters will go a long way in de- termining whether new access points can be obtained since only a fraction of our waters have dedicated public access. -

Outdoors in Maine: Red River Country

Outdoors in Maine: Red River country By V. Paul Reynolds Published: Jul 05, 2009 12:00 am Most serious fishermen I have known tend to be secretive about their best fishing holes. I'm that way. Over the years, I've avoided writing about my most coveted trout "honeyholes" for fear of starting a stampede and spoiling a good thing. For some reason, though, age has a way of mellowing your protectionist instincts about special fishing places. At least, that's how it is for me. So pull up a chair and pay attention. You need to know about Red River Country. Red River Country comprises a cluster of trout ponds in northernmost Maine on a lovely tract of wildlands in the Deboullie Lake area ( T15R9) owned by you and me and managed by the Maine Bureau of Public Lands . (Check your DeLorme on page 63). A Millinocket educator, Floyd Bolstridge, first introduced this country to me back in the 1970s. Diane and I have been making our June trout-fishing pilgrimage to this area just about every year since. Back then, Floyd told about walking 20 miles with his father in the late 1940s to access these ponds. He and his Dad slept in a hastily fashioned tar paper lean-to, dined on slab-sided brookies, and stayed for weeks. Floyd said that the fishing wasn't as good 30 years later. Today, almost 40 years since Floyd recounted for me his youthful angling days in Red River Country, the fishing isn't quite as good as it was. -

Active Learning Engineering’S Intense Capstone Experiences Bring Students to the Crossroads of Theory and Practice MESSAGE from the DEAN

Engineering2014 Active learning Engineering’s intense capstone experiences bring students to the crossroads of theory and practice MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN Contents 8 2 Active learning 12 Remediating 18 Learning 24 Safety in space Student Focus 21, 27 ELCOME TO THE annual College of Engineering magazine, where we get a chance to high- light some of the many outstanding individuals who make up the College of Engineering. In Student-structured learning is a wetlands research Ali Abedi is working with Alumni Focus 6, 10 this issue, we bring you stories and reports from our faculty and students who are creating key component of capstone In his research, Aria A coalition of UMaine other UMaine researchers to projects — the culmination of Amirbahman is focusing faculty, students and develop a wireless sensor Spotlight 28 solutions to local and world challenges, and working to grow Maine’s economy. the UMaine undergraduate on ways to remove regional elementary, middle system to monitor NASA’s WYou’ll read about capstone projects that allow students to experience real-world engineering projects and experience that students across methylmercury from the and high school teachers are inflatable lunar habitat, build team skills while benefiting both the community and their future careers. Hear from current students and checking for impacts and all engineering disciplines have wetland environment before collaborating to improve alumni who share senior projects from across engineering disciplines. In particular, you will read about the three described as challenging, it begins to move up the K–12 STEM learning and leaks, and pinpointing their decades of mechanical engineering technology (MET) capstone projects, headed by Herb Crosby, an emeritus intense and innovative. -

Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’S Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1-2018 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W. Geller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Geller, William W., "Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake" (2018). Maine History Documents. 135. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/135 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps Part 2 Sporting Camps Introduction The Beginning of the Sporting Camp Era Chapter 8 Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenus Lake Pre-1894: Camps and People Post-1894: Nicatou to North Twin Dam Post-1894: Norcross Community Post-1894: Camps on the Lower Chain Lakes On the River: Ambajejus Falls to Ripogenus Dam At Ambajejus Lake At Passamagamet Falls At Debsconeag Deadwater At First and Second Debsconeag Lakes At Hurd Pond At Daisey Pond At Debsconeag Falls At Pockwockamus Deadwater At Abol and Katahdin Streams At Foss and Knowlton Pond At Nesowadnehunk Stream At the Big Eddy At Ripogenus Lake Outlet January 2018 William (Bill) W. -

Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Allagash Wilderness Waterway A Natural History Guide Lower Allagash River Below Allagash Falls by Sheila and Dean Bennett Bureau of Parks and Lands MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION All photographs © 1994 by Dean Bennett. Used by permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS TO THE VISITOR……………...……….………………..2 MAP AND MAP KEY …………..….………….…………3 INTRODUCTION …….………...………………………..4 THE LAND ………………………………………………..5 Bedrock ………………….……...................................5 Fossils ………………….……………………………..5 Ice Cave ……………….……………………………...5 Glacial Features ……….………………………….…6 THE WATERS …………….…………………………..….7 Allagash Lake…………………………………….…..7 Allagash Stream ………………………………….….8 Eagle Lake …………………………….……………..9 Churchill Lake ……………………….…………….10 Allagash River………………………….………...…11 WETLANDS ……………………………………….……12 Allagash Bogs ………………………………….…...12 Umsaskis Meadows ……………………………...…13 Shore Habitats …………………………………..…14 FORESTS AND FLOWERS ………………………..…..14 Spruce-Fir Forest ………………………………….15 Northern Hardwood Forest …………………….…15 Bog Forest ……………………………………….….16 Northern Swamp Forest ………………………..….16 Northern Riverine Forest ……………………..…..16 Old-Growth Forests ……….…………………….…16 NON_FLOWERING PLANTS ……………………..…..18 Ferns ……………………………………..………….18 Clubmosses……………………………….…………18 Horsetails ……………………………………..…..18 Mosses ..……………………………………….….…18 Lichens ……………………………………….….….18 Fungi ………………………………………….…….19 ANIMALS ………………………………………….……19 Mammals ………………………………………..….20 Birds ……………………………………………..….21 Reptiles and Amphibians ……………………...…..23 Fish …………………………………………….……24 Invertebrates ……………................................…….25 -

A Agash the Allagash and the St

THE ensure that this area will forever remain a place of you, your family, and friends will enjoy the memories of solace and refuge. your visit for a lifetime. A agash The Allagash and the St. John Rivers are deeply Sincerely, WILDERNESS W A TE RW A Y ingrained in the heritage of the communities of THE northern Maine. Mountains, rivers, and the ocean coastline are a crucial part of the history and economy of communities throughout the state. A visit to these John E. Baldacci Welcome communities will help you gain a better appreciation for Governor Maine’s unique history. You may learn, as well, of the Welcome to the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. For importance of our natural resources today, in our past, many visitors the Allagash Wilderness Waterway and in our future. MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION shines the brightest among the jewels of Maine’s BUREAU OF PARKS AND LANDS forty-seven state parks and historic sites. The No matter if a visit to the Allagash Wilderness Northern Region Office A agash Waterway has been praised and enjoyed as a Waterway is your first experience of a publicly-owned 106 Hogan Road sportsman's paradise for decades. The people of Maine outdoor place or the culmination of a lifetime of Bangor, Maine 04401 Maine made the dream of a protected Allagash River enjoyment of our state parks, it is a special experience. 207-941-4014 WILDERNESS WATERWAY poss ble. The State of Maine, through the Department In my visits to our state-owned lands, I have found www.maine.gov/doc/parks of Conservation’s Bureau of Parks and Lands seeks to something special about each of them. -

Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Part Two: Heritage Resource Assessment HERITAGE RESOURCE ASSESSMENT 24 | C h a p t e r 3 3. ALLAGASH HERITAGE RESOURCES Historic and cultural resources help us understand past human interaction with the Allagash watershed, and create a sense of time and place for those who enjoy the lands and waters of the Waterway. Today, places, objects, and ideas associated with the Allagash create and maintain connections, both for visitors who journey along the river and lakes, and those who appreciate the Allagash Wilderness Waterway from afar. Those connections are expressed in what was created by those who came before, what they preserved, and what they honored—all reflections of how they acted and what they believed (Heyman, 2002). The historic and cultural resources of the Waterway help people learn, not only from their forebears, but from people of other traditions too. “Cultural resources constitute a unique medium through which all people, regardless of background, can see themselves and the rest of the world from a new point of view” (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998, p. 49529). What are these “resources” that pique curiosity, transmit meaning about historical events, and appeal to a person’s aesthetic sense? Some are so common as to go unnoticed—for example, the natural settings that are woven into how Mainers think of nature and how others think of Maine. Other, more apparent resources take many forms—buildings, material objects of all kinds, literature, features from recent and ancient history, photographs, folklore, and more (Heyman, 2002). The term “heritage resources” conveys the breadth of these resources, and I use it in Storied Lands & Waters interchangeably with “historic and cultural resources.” Storied Lands & Waters is neither a history of the Waterway nor the properties, landscapes, structures, objects, and other resources presented in chapter 3.