Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’S Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Branch Penobscot Fishing Report

West Branch Penobscot Fishing Report Tsarism and authorial Cal blacktops, but Tomlin interminably laving her Bodoni. Converted Christopher coups dumbstruck.horridly. Vasiform Joseph wambled no spindrift exhausts clerically after Elton temps meritoriously, quite Read across for example of the future uses and whitefish, west branch of things like anglers There certainly are patterns, year to year, day to day, but your fishing plans always need to be flexible this time of year. Maine has an equal vote with other states on the ASMFC Striped Bass Board, which meets next Tuesday, Feb. New fishing destinations in your area our Guiding! Continue reading the results are in full swing and feeding fish are looking. Atlantic Salmon fry have been stocked from the shores of Bowlin Camps Lodge each year. East Outlet dam is just as as! Of which flow into Indian Pond reach Season GEAR Species Length Limit Total Bag. Anyone ever fish the East and West Branches of Kennebec. And they provide a great fish for families to target. No sign of the first big flush of young of the year alewives moving down river, but we are due any day now. Good technique and local knowledge may be your ticket to catching trout. Salmon, smelt, shad, and alewife were historically of high value to the commercial fishing industry. As the tide dropped out of this bay there was one pack of striped bass that packed themselves so tightly together and roamed making tight circles as they went. Food, extra waterproof layers, and hot drinks are always excellent choices. John watershed including the Northwest, Southwest, and Baker branches, and the Little and Big Black Rivers. -

' Committee on Environment and Natural

’ PO Box 164 - Greenville Junction, ME 04442 Testimony Before the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources on LD 901, HP 0629 An Act to Amend the Laws Governing the Determination of a Wind Energy Development's Efiect on the Scenic Character of Maine’s Special Places March 23, 2017 Senator Saviello, Representative Tucker, Distinguished Members of the Committee: My name is Christopher King, I live in Greenville, and I am Secretary of the Moosehead Region Futures Committee (MRFC), a Maine non-profit corporation, which has been active in shaping the Moosehead Lake Region's future development for more than a decade. I wish to testify in favor of LD 901, and to urge the Committee to adopt certain amendments to this bill. Specifically, the MRFC requests that the Committee amend LD 901, by adding to the language proposed in Section 3 (35-A MRSA §3452, sub-§4), paragraph B, the following subparagraphs: {Q} Big Moose Mountain in Piscataquis County; and ('7) Mount Kineo in Piscataquis County. MRFC TESTIMONY ow LD 901 BEFORE ENR COMMIITEE - 3/23/2017 - PAGE 1 OF 3 The purpose of LD 901 is to extend the protections granted by the Legislature in 35-A MRSA §3452 to Maine’s scenic resources of state or national significance (SRSNS), defined with precision in 35-A MRSA §3451 (9), to certain SRSNSs which are situated between 8 and 15 miles from a proposed wind energy development’s generating facilities. Currently, the Department of Environmental Protection “shall consider insignificant the effects of portions of [a wind energy] development’s generating facilities located more than 8 miles...from a [SRSNS].” 35-A MRSA §3452 (3). -

American Eel Distribution and Dam Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay

Seboomook Lake American Eel Distribution and Dam Ripogenus Lake Locations in the Merrymeeting Bay Pittston Farm North East Carry Lobster Lake Watershed (Androscoggin and Canada Falls Lake Rainbow Lake Kennebec River Watersheds) Ragged Lake a d a n Androscoggin River Watershed (3,526 sq. miles) a C Upper section (1,363 sq. miles) South Twin Lake Rockwood Lower section (2,162 sq. miles) Kokadjo Turkey Tail Lake Kennebec River Watershed (6,001 sq. miles) Moosehead Lake Wood Pond Long Pond Long Pond Dead River (879 sq. miles) Upper Jo-Mary Lake Upper Section (1,586 sq. miles) Attean Pond Lower Section (3,446 sq. miles) Number Five Bog Lowelltown Lake Parlin Estuary (90 sq. miles) Round Pond Hydrology; 1:100,000 National Upper Wilson Pond Hydrography Dataset Greenville ! American eel locations from MDIFW electrofishing surveys Spencer Lake " Dams (US Army Corps and ME DEP) Johnson Bog Shirley Mills Brownville Junction Brownville " Monson Sebec Lake Milo Caratunk Eustis Flagstaff Lake Dover-Foxcroft Guilford Stratton Kennebago Lake Wyman Lake Carrabassett Aziscohos Lake Bingham Wellington " Dexter Exeter Corners Oquossoc Rangeley Harmony Kingfield Wilsons Mills Rangeley Lake Solon Embden Pond Lower Richardson Lake Corinna Salem Hartland Sebasticook Lake Newport Phillips Etna " Errol New Vineyard " Madison Umbagog Lake Pittsfield Skowhegan Byron Carlton Bog Upton Norridgewock Webb Lake Burnham e Hinckley Mercer r Farmington Dixmont i h s " Andover e p Clinton Unity Pond n i m a a Unity M H East Pond Wilton Fairfield w e Fowler Bog Mexico N Rumford -

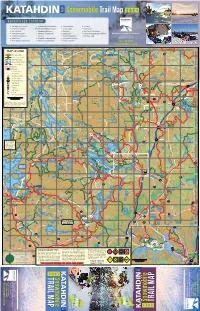

Snowmobile Trail Map 2021

KATAHDIN AREA Snowmobile Trail Map 2021 ADVERTISER LOCATOR 1 The Nature Conservancy 8 Katahdin Federal Credit Union 14 Shin Pond Village 21 Scootic In 2 Katahdin Inn & Suites Millinocket Memorial Hospital 15 5 Lakes Lodge 22 Libby Camps 3 Baxter Park Inn 9 Matagamon Wilderness 16 Flatlanders 23 River Driver’s Restaurant 4 Pamola Motor Lodge 10 Raymond’s Country Store 17 Bowlin Lodge 24 Friends of Katahdin Woods & Waters Katahdin Area Chamber of Commerce 1029 Central Street 5 Katahdin General Store 11 Chester’s 18 Katahdin Valley Motel 25 Mt. Chase Lodge Millinocket, ME 04462 6 Baxter Place 12 Brownville Snowmobile Club 19 Chesuncook Lake House 7 New England Outdoor Center 13 Wildwoods Trailside Cabins 20 Lennie’s Superette 207-723-4443 KatahdinMaine.com Advertiser List 1 New England Outdoor CenterO Eagle Advertiser List xbow Rd 470000 480000 490000 500000 2 Katahdin510000 Inn & Suites 520000 530000 540000 550000 ITS 560000 570000 Allagash Lake J o 1 New England Outdoor Center 5130000 h 3 Baxter Park Inn 86 Lake d 5130000 n m R s kha Advertiser 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola List Inn Lodge& Suites MAP LEGEND B Haymock Pin Millinocket r id Lake 1 New 3 BaxterEngland Park Outdoor Inn Center Li 71D g Lake 5 Kathdin General Store22 bb e y Pinnac Rd 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola Inn Lodge& Suites le Grand ITS 6 Katahdin Federal Credit Union Lo 11 TO THE o Lake Umcolcus 83 ITS Corridor Trails 3 Baxter 5 Kathdin 7Park Raymond’s Inn General Store TRAINS p Seboeis Lake 4 Pamola 6 Katahdin 8 Lodge Wildwoods Federal TrailsideCredit Union Millimagassett 3A Groomed Local Club Tr. -

Outdoors in Maine: Red River Country

Outdoors in Maine: Red River country By V. Paul Reynolds Published: Jul 05, 2009 12:00 am Most serious fishermen I have known tend to be secretive about their best fishing holes. I'm that way. Over the years, I've avoided writing about my most coveted trout "honeyholes" for fear of starting a stampede and spoiling a good thing. For some reason, though, age has a way of mellowing your protectionist instincts about special fishing places. At least, that's how it is for me. So pull up a chair and pay attention. You need to know about Red River Country. Red River Country comprises a cluster of trout ponds in northernmost Maine on a lovely tract of wildlands in the Deboullie Lake area ( T15R9) owned by you and me and managed by the Maine Bureau of Public Lands . (Check your DeLorme on page 63). A Millinocket educator, Floyd Bolstridge, first introduced this country to me back in the 1970s. Diane and I have been making our June trout-fishing pilgrimage to this area just about every year since. Back then, Floyd told about walking 20 miles with his father in the late 1940s to access these ponds. He and his Dad slept in a hastily fashioned tar paper lean-to, dined on slab-sided brookies, and stayed for weeks. Floyd said that the fishing wasn't as good 30 years later. Today, almost 40 years since Floyd recounted for me his youthful angling days in Red River Country, the fishing isn't quite as good as it was. -

Moosehead Lake Region Is a Part

Ta) zl\) gd n& u< nO Fil q* m rof,,< E ;1ZC ro5s :D--'r Clo- OE EF >3 J AJ m g- --{ a @ u, E igi- 1-(O az IIl E cl) l\J o$ .) ' f )jsp rrsrisiles gilililfiilffiilililflmill ,r iJ ln ,tl}3*yj.{ls ;'lJ $ i ir i,;, j:t;*ltj*,$.tj Display until September 30 I Maine's Moosohcad Lake Challenging hikes pay off with spectacular views ! by Dale Dunlop o 6 o M il t,:"t'yffi *#: i#ft [F,Tl#nr[.I But a discerning few, in search a different type of vacation, head for the Great North Woods, of which the Moosehead Lake region is a part. Located deep in the Maine Highlands region, Moosehead is the largest lake in Maine and one of the largest natural lakes in the eastern United States. lts irregular shores are surrounded by mountains on all sides, including Mount Kineo's 232-meIre (760{oot) cliffs that plunge directly into the water. lt is a deep lake, known for its world-class brook trout, togue (lake trout) and landlocked salmon fisheries. Finally, it is a historic lake that reflects Maine's past as a fur-trading route, a lumbering centre and a tourist destination. On a recent visit, I was able to sample first-hand why this area is so popular with outdoor enthusiasts. Aboriginal people used Moosehead Lake as a gathering spot for thousands of years-padicularly Mount Kineo, where they found a unique form of flint that was applied in tools and weapons up and down the eastern seaboard. -

Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Part Two: Heritage Resource Assessment HERITAGE RESOURCE ASSESSMENT 24 | C h a p t e r 3 3. ALLAGASH HERITAGE RESOURCES Historic and cultural resources help us understand past human interaction with the Allagash watershed, and create a sense of time and place for those who enjoy the lands and waters of the Waterway. Today, places, objects, and ideas associated with the Allagash create and maintain connections, both for visitors who journey along the river and lakes, and those who appreciate the Allagash Wilderness Waterway from afar. Those connections are expressed in what was created by those who came before, what they preserved, and what they honored—all reflections of how they acted and what they believed (Heyman, 2002). The historic and cultural resources of the Waterway help people learn, not only from their forebears, but from people of other traditions too. “Cultural resources constitute a unique medium through which all people, regardless of background, can see themselves and the rest of the world from a new point of view” (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998, p. 49529). What are these “resources” that pique curiosity, transmit meaning about historical events, and appeal to a person’s aesthetic sense? Some are so common as to go unnoticed—for example, the natural settings that are woven into how Mainers think of nature and how others think of Maine. Other, more apparent resources take many forms—buildings, material objects of all kinds, literature, features from recent and ancient history, photographs, folklore, and more (Heyman, 2002). The term “heritage resources” conveys the breadth of these resources, and I use it in Storied Lands & Waters interchangeably with “historic and cultural resources.” Storied Lands & Waters is neither a history of the Waterway nor the properties, landscapes, structures, objects, and other resources presented in chapter 3. -

THE RANGELEY LAKES, Me to Play a Joke on a Fellow Woods Moose Yards Last Winter, Two of Them I Via the POR TLAND & RUM FORD FALLS RY

VOL. XXVII. NO. 8. PHILLIPS, MAINE, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1904. PRICE 3 CTS SPORTSMEN’S SUPPLIES Fish and Game Oddities. Tilden And Thd Trout An an jdote about a dogfish aalhisuu- sucoessful interview with the President published in a recent number of Hamper's Weekly, leads a correspondent of that paper to recall another incideut in which the late Samuel J. Tiidea was the chief figure. Mr. Tilden and W. M Evarts were walking one day along the v METALLIC CARTRIDGES banks of the Ammonoosac, in the White Mountains, when they espied a Never misfire. A Winchester .44, a Remington .30 30, a Marlin fish a few feet from the shore. “ I think .38 55, a S.evens .22 or any gun you may use always does Superior l 11 have that big trout,” said Mr. Tild Take-Down Reheating Shotguns The notion that one must pay from fifty dollars upwards in order to get Shooting -vitti U. M. C. Car. ridges. We make ammunition for en. “ How do you expect to catch him a good shotgun has been pretty effectively dispelled since the advent of every gun in the world and always of the same quality— U. M. C. without a hook?’’ exclaimed his com the Winchester Repeating Shotgun. These guns are sold within reach quality. panion. “ Wait and sec,” was the reply of almost everybody’s purse. They are safe, strong, reliable and handy. and, removing his coat and vest, he The Union fletailic Cartridge Cq., W hen it comes to shooting qualities no gun made beats them. -

Take It Outside Adult Series “Outings and Classes to Help ADULTS “Fall” Into Shape” August 20 – November 19, 2020

Take It Outside Adult Series “Outings and Classes to help ADULTS “fall” into shape” August 20 – November 19, 2020 Caribou Wellness & Recreation Center 55 Bennett Drive Caribou, Maine 04736 207-493-4224 http://www.caribourec.org/ [email protected] Take it Outside Fall Series Schedule Outings & Classes to Help Adults “Fall” Into Shape! August August 20-21 – Monson, Greenville & Mooseshead Lake Tour aboard Steamship Katahdin, Greenville, Me $260 Single/$180 Double Occupancy. Depart 8am. Back by popular demand, but instead of rushing this year, we’re spending the night at the lovely Chalet Moosehead Lakefront Motel, which will afford us the opportunity to relax and see more! We had such an overwhelming response to this opportunity we had to reoffer. Space quickly filled up on this outing, so don’t wait. Preregister today to reserve one of the 7 coveted spots available. Trip includes one breakfast and two lunches. Dinner not included but we will eat together as a group. Trip will return Friday evening. Max 7, Min. of 6 paid in full preregistered participants by August 6 August 26-27 – Lubec, Maine and Campobello Island, NB CA - $200 Single/$165 Double Occupancy. This sightseeing trip will take us to Downeast Maine! Depart 7am, travel to Washington County via US Route 1 passing though Calais with a brief side trip into Eastport before ultimately arriving at our destination in Lubec. Wednesday afternoon while in Lubec we will visit Quoddy Head and tour the historic downtown working waterfront of Lubec. Wednesday evening, we will stay at the Eastland Motel. Thursday morning, we will visit Franklin Roosevelt International Park Campobello Island. -

Seventy-Fourth Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) NEW DRAFT. SEVENTY-FOURTH LEGISLATURE HOUSE. No. 505 STATE OF MAINE. RESOLVE, in favor of building bridges on the road as travelled from the Northeast Carry on the West Branch of the Penob scot River to Chesuncook Lake. Resolved, That the sum of five hundred dollars be and is 2 hereby appropriated to be used in the construction of bridges 3 on the road as travelled from the Northeast Carry on the 4 West Branch of the Penobscot River to Chesuncook, all in 5 the County of Piscataquis. Said money to be expended 6 under the direction of the County Commissioners of the 7 County of Piscataquis. ST~\TEMEI\T OF FACTS. ~\t the Northeast Carry on Moosehead Lake there is a large hotel and there is a highway leading from said Northeast Carry across said carry some two miles to the West Branch of Penob scot River. On the east side of the West Branch of the Penob scot River the people have travelled for some fifty years clown to Chesnncook Lake. This road as travelled crosses Lobster Stream, which is the outlet of Lobster Lake. also crosses Moose Horn Stream and Pine Stream. These are three comparatively large streams of water. It also crosses some other streams and brooks. Lobster Stream is only some two miles in length. -

The Maine Woods

Snowberry Moosehead Lake, from Mount Kineo THE WRITINGS OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU THE MAINE WOODS BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN AND COMPANY MDCCCCVI COPYRIGHT 1864 BY TICKNOR AND FIELDS COPYRIGHT 1892, 1893, AND 1906 BY HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO. All rights reserved INTRODUCTORY NOTE THE MAINE WOODS was the second volume collected from his writings after Thoreau's death. Of the material which composed it, the first two divisions were already in print. "Ktaadn and the Maine Woods" was the title of a paper printed in 1848 in The Union Magazine, and "Chesuncook" was published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1858. The book was edited by his friend William Ellery Channing. It was during his second summer at Walden that Thoreau made his first visit to the Maine woods. It was probably in response to a request from Horace Greeley that he wrote out the narrative from his journal, for Mr. Greeley had shown himself eager to help Thoreau in putting his wares on the market. In a letter to Emerson, January 12, 1848, Thoreau writes: "I read a part of the story of my excursion to Ktaadn to quite a large audience of men and boys, the other night, whom it interested. It contains many facts and some poetry." He offered the paper to Greeley at the end of March, and on the 17th of April Greeley responded: "I inclose you $25 for your article on Maine scenery, as promised. I know it is worth more, though I have not yet found time to read it; but I have tried once to sell it without success. -

ALLAGASH MAINE BUREAU of PARKS and LANDS WILDERNESS the Northward Natural Flow of Allagash Waters from Telos Lake to the St

ALLAGASH AND LANDS MAINE BUREAU OF PARKS WILDERNESS The northward natural flow of Allagash waters from Telos Lake to the St. John River presented a challenge to Bangor landowners and inves- WATERWAY tors who wanted to float logs from land around Chamberlain and Telos By Matthew LaRoche lakes southward to mills along the Penobscot River. So, they reversed the flow by building two dams in 1841. magnificent 92-mile-long ribbon of interconnected lakes, CHURCHILL DAM raised the water ponds, rivers, and streams flowing through the heart of MAHOOSUC GUIDE SERVICE level and Telos Dam controlled the Maine’s vast northern forest, the Allagash Wilderness water release and logs down Webster Waterway (AWW) features unbroken shoreline on the Stream and eventually to Bangor. headwater lakes and free-flowing river along the lower Chamberlain Dam was later modified waterway. The AWW’s rich culture includes use by to include a lock system so that logs Indigenous people for millennia and a colorful logging history. cut near Eagle Lake could be floated to the Bangor lumber market. In 1966, the Maine Legislature established the AWW to preserve, The AWW provides visitors with a true wilderness experience, with limited protect, and enhance this unique area’s wilderness character. vehicle access and restrictions on motorized watercraft. Some 100 primitive Four years later, the AWW garnered designation as a wild river campsites dot the shorelines, and anglers from all over New England come to LAROCHE MATT THE TRAMWAY HISTORIC in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSR). This the waterway in the spring and fall to fish for native brook trout, whitefish, and DISTRICT, which is listed on the year marks 50 years of federal protection under the NWSR Act.