Easements and Conservation Policy in the North Maine Woods David J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

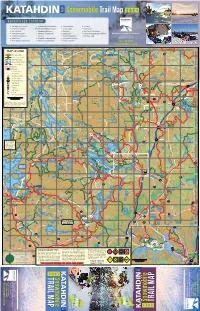

Snowmobile Trail Map 2021

KATAHDIN AREA Snowmobile Trail Map 2021 ADVERTISER LOCATOR 1 The Nature Conservancy 8 Katahdin Federal Credit Union 14 Shin Pond Village 21 Scootic In 2 Katahdin Inn & Suites Millinocket Memorial Hospital 15 5 Lakes Lodge 22 Libby Camps 3 Baxter Park Inn 9 Matagamon Wilderness 16 Flatlanders 23 River Driver’s Restaurant 4 Pamola Motor Lodge 10 Raymond’s Country Store 17 Bowlin Lodge 24 Friends of Katahdin Woods & Waters Katahdin Area Chamber of Commerce 1029 Central Street 5 Katahdin General Store 11 Chester’s 18 Katahdin Valley Motel 25 Mt. Chase Lodge Millinocket, ME 04462 6 Baxter Place 12 Brownville Snowmobile Club 19 Chesuncook Lake House 7 New England Outdoor Center 13 Wildwoods Trailside Cabins 20 Lennie’s Superette 207-723-4443 KatahdinMaine.com Advertiser List 1 New England Outdoor CenterO Eagle Advertiser List xbow Rd 470000 480000 490000 500000 2 Katahdin510000 Inn & Suites 520000 530000 540000 550000 ITS 560000 570000 Allagash Lake J o 1 New England Outdoor Center 5130000 h 3 Baxter Park Inn 86 Lake d 5130000 n m R s kha Advertiser 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola List Inn Lodge& Suites MAP LEGEND B Haymock Pin Millinocket r id Lake 1 New 3 BaxterEngland Park Outdoor Inn Center Li 71D g Lake 5 Kathdin General Store22 bb e y Pinnac Rd 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola Inn Lodge& Suites le Grand ITS 6 Katahdin Federal Credit Union Lo 11 TO THE o Lake Umcolcus 83 ITS Corridor Trails 3 Baxter 5 Kathdin 7Park Raymond’s Inn General Store TRAINS p Seboeis Lake 4 Pamola 6 Katahdin 8 Lodge Wildwoods Federal TrailsideCredit Union Millimagassett 3A Groomed Local Club Tr. -

Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’S Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1-2018 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W. Geller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Geller, William W., "Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake" (2018). Maine History Documents. 135. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/135 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps Part 2 Sporting Camps Introduction The Beginning of the Sporting Camp Era Chapter 8 Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenus Lake Pre-1894: Camps and People Post-1894: Nicatou to North Twin Dam Post-1894: Norcross Community Post-1894: Camps on the Lower Chain Lakes On the River: Ambajejus Falls to Ripogenus Dam At Ambajejus Lake At Passamagamet Falls At Debsconeag Deadwater At First and Second Debsconeag Lakes At Hurd Pond At Daisey Pond At Debsconeag Falls At Pockwockamus Deadwater At Abol and Katahdin Streams At Foss and Knowlton Pond At Nesowadnehunk Stream At the Big Eddy At Ripogenus Lake Outlet January 2018 William (Bill) W. -

THE RANGELEY LAKES, Me to Play a Joke on a Fellow Woods Moose Yards Last Winter, Two of Them I Via the POR TLAND & RUM FORD FALLS RY

VOL. XXVII. NO. 8. PHILLIPS, MAINE, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1904. PRICE 3 CTS SPORTSMEN’S SUPPLIES Fish and Game Oddities. Tilden And Thd Trout An an jdote about a dogfish aalhisuu- sucoessful interview with the President published in a recent number of Hamper's Weekly, leads a correspondent of that paper to recall another incideut in which the late Samuel J. Tiidea was the chief figure. Mr. Tilden and W. M Evarts were walking one day along the v METALLIC CARTRIDGES banks of the Ammonoosac, in the White Mountains, when they espied a Never misfire. A Winchester .44, a Remington .30 30, a Marlin fish a few feet from the shore. “ I think .38 55, a S.evens .22 or any gun you may use always does Superior l 11 have that big trout,” said Mr. Tild Take-Down Reheating Shotguns The notion that one must pay from fifty dollars upwards in order to get Shooting -vitti U. M. C. Car. ridges. We make ammunition for en. “ How do you expect to catch him a good shotgun has been pretty effectively dispelled since the advent of every gun in the world and always of the same quality— U. M. C. without a hook?’’ exclaimed his com the Winchester Repeating Shotgun. These guns are sold within reach quality. panion. “ Wait and sec,” was the reply of almost everybody’s purse. They are safe, strong, reliable and handy. and, removing his coat and vest, he The Union fletailic Cartridge Cq., W hen it comes to shooting qualities no gun made beats them. -

Seventy-Fourth Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) NEW DRAFT. SEVENTY-FOURTH LEGISLATURE HOUSE. No. 505 STATE OF MAINE. RESOLVE, in favor of building bridges on the road as travelled from the Northeast Carry on the West Branch of the Penob scot River to Chesuncook Lake. Resolved, That the sum of five hundred dollars be and is 2 hereby appropriated to be used in the construction of bridges 3 on the road as travelled from the Northeast Carry on the 4 West Branch of the Penobscot River to Chesuncook, all in 5 the County of Piscataquis. Said money to be expended 6 under the direction of the County Commissioners of the 7 County of Piscataquis. ST~\TEMEI\T OF FACTS. ~\t the Northeast Carry on Moosehead Lake there is a large hotel and there is a highway leading from said Northeast Carry across said carry some two miles to the West Branch of Penob scot River. On the east side of the West Branch of the Penob scot River the people have travelled for some fifty years clown to Chesnncook Lake. This road as travelled crosses Lobster Stream, which is the outlet of Lobster Lake. also crosses Moose Horn Stream and Pine Stream. These are three comparatively large streams of water. It also crosses some other streams and brooks. Lobster Stream is only some two miles in length. -

ALLAGASH MAINE BUREAU of PARKS and LANDS WILDERNESS the Northward Natural Flow of Allagash Waters from Telos Lake to the St

ALLAGASH AND LANDS MAINE BUREAU OF PARKS WILDERNESS The northward natural flow of Allagash waters from Telos Lake to the St. John River presented a challenge to Bangor landowners and inves- WATERWAY tors who wanted to float logs from land around Chamberlain and Telos By Matthew LaRoche lakes southward to mills along the Penobscot River. So, they reversed the flow by building two dams in 1841. magnificent 92-mile-long ribbon of interconnected lakes, CHURCHILL DAM raised the water ponds, rivers, and streams flowing through the heart of MAHOOSUC GUIDE SERVICE level and Telos Dam controlled the Maine’s vast northern forest, the Allagash Wilderness water release and logs down Webster Waterway (AWW) features unbroken shoreline on the Stream and eventually to Bangor. headwater lakes and free-flowing river along the lower Chamberlain Dam was later modified waterway. The AWW’s rich culture includes use by to include a lock system so that logs Indigenous people for millennia and a colorful logging history. cut near Eagle Lake could be floated to the Bangor lumber market. In 1966, the Maine Legislature established the AWW to preserve, The AWW provides visitors with a true wilderness experience, with limited protect, and enhance this unique area’s wilderness character. vehicle access and restrictions on motorized watercraft. Some 100 primitive Four years later, the AWW garnered designation as a wild river campsites dot the shorelines, and anglers from all over New England come to LAROCHE MATT THE TRAMWAY HISTORIC in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSR). This the waterway in the spring and fall to fish for native brook trout, whitefish, and DISTRICT, which is listed on the year marks 50 years of federal protection under the NWSR Act. -

North Maine Woods2013 $3

experience the tradition North Maine Woods2013 $3 On behalf welcomeof the many families, private corporations, conservation organizations and managers of state owned land, we welcome you to this special region of Maine. We’re proud of the history of this remote region and our ability to keep this area open for public enjoyment. In addition to providing remote recreational opportunities, this region is also the “wood basket” that supports our natural resource based economy of Maine. This booklet is designed to help you have a safe and enjoyable trip to the area, plus provide you with important information about forest resource management and recreational use. P10 Katahdin Ironworks Jo-Mary Forest Information P14 New plan for the Allagash Wilderness Waterway P18 Moose: Icon of P35 Northern Region P39 Sharing the roads the North Woods Fisheries Update with logging trucks 2013 Visitor Fees NMW staff by photo RESIDENT NON-RESIDENT Under 15 .............................................................. Free Day Use & Camping Age 70 and Over ............................................... Free Day Use Per Person Per Day ...................................................$7 ................ $12 Camping Per Night ....................................................$10 ............. $12 Annual Day Use Registration ...............................$75 ............. N/A Annual Unlimited Camping ..................................$175 .......... N/A Checkpoint Hours of Operation Camping Only Annual Pass ...................................$100 .......... $100 Visitors traveling by vehicle will pass through one of the fol- lowing checkpoints. Please refer to the map in the center of Special Reduced Seasonal Rates this publication for locations. Summer season is from May 1 to September 30. Fall season is from August 20 to November 30. Either summer or fall passes NMW Checkpoints are valid between August 20 and September 30. Allagash 5am-9pm daily Caribou 6am-9pm daily Seasonal Day Use Pass ............................................$50 ............ -

AMERICAN INDIAN TRIBAL CENSUS TRACT OUTLINE MAP (CENSUS 2000) 68.612442W Loon Lake

46.141224N 46.141224N 69.745939W AMERICAN INDIAN TRIBAL CENSUS TRACT OUTLINE MAP (CENSUS 2000) 68.612442W Loon Lake Telos Lake Hay Lake Black LEGEND Pond SYMBOL NAME STYLE INTERNATIONAL Cuxabexis Lake Jerry Pond AIR (FEDERAL) Trust Land Umbazooksus Stream OTSA / TDSA AMERICAN INDIAN TRIBAL SUBDIVISION Moose AIR (State) Brandy Pond Pond SDAISA Place within Subject Entity Incorporated Place / CDP W Branch Penobscot River Nesowadnehunk Place outside of Subject Entity Lake Duck Pond Incorporated Place / CDP Pine Stream Tribal Census Tract 1 ABBREVIATION REFERENCE: AIR = American Indian Reservation; Trust Land = Off−Reservation Trust Land; OTSA = Oklahoma Tribal; Statistical Area; TDSA = Tribal Designated Statistical Area; SDAISA = State Designated American Indian Statistical Area; CDP = Census Designated Place Lunksoos Lake Cassidy Deadwater PISCATAQUIS 021 PENOBSCOT 019 Mud Pond Quaker Brook Military Out Area Harrington Lake Inset Seboeis River 1 This map shows tribal census tract boundaries and numbers. A tribal census tract is a type of census tract defined within a federally Pine Stream Flowage Katahdin Lake recognized American Indian reservation or off−reservation trust land for the purpose of providing data based on an American Indiani hierarchy rather than by state and county. West Branch Penobscot River Chesuncook Lake Russell Stream PISCATAQUIS 021 West Branch Penobscot River E Branch Penobscot River Bald Mt Twp W assataquoik Stream SOMERSET 025 Little Lobster Lake Ripogenus Lake W Branch Penobscot River Lobster Stream Caribou Lake -

St John Ponds Parcel +/- 3, 895 Acres 11 Miles of Frontage Canada Falls Lake / South Branch Penobscot River Parcel +/- 810 Acres

BraileyBrailey BrookBrook BraileyBrailey BrookBrook EastEast BranchBranch AllagashAllagash StreamStream CedarCedar BrookBrook Ronald B. Lovaglio, Commissioner T8 R19 WELS T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R10 WELS John Thomas A. Morrison, Director BuckleyBuckley PondPond SmithSmith BrookBrook LittleLittle PillsburyPillsbury PondPond SaintSaint FrancisFrancis LakeLake AllagashAllagash LakeLake SmithSmith BrookBrook LittleLittle PillsburyPillsbury PondPond SaintSaint FrancisFrancis LakeLake BuckleyBuckley BrookBrook AllagashAllagash StreamStream BuckleyBuckley BrookBrook HaymockHaymock LakeLake Baker Lake Parcel +/- 1, 625 acres HaymockHaymock LakeLake HayHay PondPond BigBig CaribouCaribou PondPond WoodmanWoodman PondPond 13 miles of frontage MartinMartin CoveCove WoodmanWoodman PondPond CarpenterCarpenter PondPond LowerLower EllisEllis PondPond LittleLittle MooseMoose PondPond St. LowerLower EllisEllis PondPond T7 R19 WELS T7 R18 WELS T7 R17 WELS SaintT7 R16 WELS T7 R15 WELS T7 R14 WELS T7 R13 WELS T7 R12 WELS T7 R11 WELS T7 R10 WELS West Branch Project AveryAvery PondPond SlySly BrookBrook DaggettDaggett PondPond EllisEllis BogBog GrayGray BrookBrook DaggettDaggett PondPond BrayleyBrayley BrookBrook Fee Component Under Option ChamberlainChamberlain LakeLake BrayleyBrayley BrookBrook To State of Maine CaucomgomocCaucomgomoc LakeLake +/- 46, 895 acres (4 Parcels) CarryCarry BrookBrook CaucomgomocCaucomgomoc LakeLake SmithSmith BrookBrook BogBog John SmithSmith BrookBrook -

Penobscot River Corridor & Seboomook Public Land

www.parksandlands.com Property History When to Visit Bureau of Parks and Lands and Parks of Bureau he rivers, streams, and lakes in the Seboomook/Pe- The best paddling is between May and September, with the fish- nobscot region were highways for native people, who ing usually best in either of those “shoulder season” months. Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry and Conservation Agriculture, Thave been present here for nearly 12,000 years. Canoe Recreational dam releases tend to occur on Saturdays during routes in the region date back at least 1,000 years, linking the July, August and September: call GLHA at 1- 888-323-4341 Maine Department of Department Maine Kennebec, Penobscot, and Allagash rivers, are still enjoyed for more on Canada Falls and Seboomook dam releases. For today by recreational paddlers traveling the historic 740-mile more on timing of McKay Station (Ripogenus Dam) releases, Northern Forest Canoe Trail. call Brookfield Power at 1-888-323-4341. Some of these paddling routes were taken by writer and naturalist Mosquitoes and black flies are thickest in late May through Overview Upper West Branch and Lobster Lake Henry David Thoreau on three extended trips between 1846 and July. Various types of hunting take place in fall, with bear bait 1857. Thoreau’s The Maine Woods describes his journey into a season generally during September, moose hunting from late he upper reaches of the Penobscot River run through a The wildest portion of the corridor, the Upper West Branch wild landscape that attracted both adventurers and lumbermen. September through mid-October, and firearms season for deer mountainous, forested landscape defined by the power- offers scenic canoeing, camping and fishing (with gentle waters in November. -

Maine Revised Statutes 38 §467

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Maine Revised Statutes 38 §467 Maine Revised Statutes Title 38: WATERS AND NAVIGATION Chapter 3: PROTECTION AND IMPROVEMENT OF WATERS Subchapter 1: ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION BOARD Article 4-A: WATER CLASSIFICATION PROGRAM §467. Classification of major river basins All surface waters lying within the boundaries of the State that are in river basins having a drainage area greater than 100 square miles that are not classified as lakes or ponds are classified in this section. [1989, c. 764, §2 (AMD).] 1. Androscoggin River Basin. A. Androscoggin River, main stem, including all impoundments. (1) From the Maine-New Hampshire boundary to its confluence with the Ellis River - Class B. (2) From its confluence with the Ellis River to a line formed by the extension of the Bath-Brunswick boundary across Merrymeeting Bay in a northwesterly direction - Class C. [1989, c. 890, Pt. A, §40 (AFF); 1989, c. 890, Pt. B, §68 (AMD); MRSA T. 38, §467, sub-§1, ¶ A (AMD).] B. Little Androscoggin River Drainage. (1) Little Androscoggin River, main stem. (a) From the outlet of Bryant Pond to the Maine Central Railroad bridge in South Paris - Class A. (b) From the Maine Central Railroad bridge in South Paris to its confluence with the Androscoggin River - Class C. -

Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1938 Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game

Maine State Library Digital Maine Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 4-21-1938 Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1938 Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game, "Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1938" (1938). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 65. https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/65 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maine INLAND ICE FISHING LAWS 1 9 3 8 V ’ * I 1 ^ ^ • ICE FISHING LAWS The waters, listed by Counties, in this pamphlet are separated into groups which are governed by the same laws GENERAL LAW Except as otherwise specified herein, it is illegal to fish for any kind of fish in waters which are closed to fishing for salmon, trout and togue. Bass cannot be taken through the ice at any time. Persons properly licensed may lish through the ice in the daytime with 5 set lines each, when under the immediate supervision of the person fishing, and in the night time for cusk in such waters as are open for fish ing in the night time for cusk. Non-residents over 10 years of age and residents over 18 years of age m ust be licensed. Sec. 27. Fishing for gain or hire prohibited; exceptions; penalty. -

Canoe Camping and Fishing Trips in the Northern Maine Woods Most Trips in the North Woods Are to Be Guided by Myself, Blaine Mi

Canoe Camping and Fishing Trips in The and usually pike in these rivers. On some Dates and Locations Allagash Lake to Churchill Dam 7 Days Northern Maine Woods Canadian trips you may be required to provide Variations of these trips can be made upon After leaving Norridgewock, we will drive Most trips in the North Woods are to be guided your own transportation to an agreed upon request. Trips can be scheduled from May to Allagash Stream or Johnson Pond. From here by myself, Blaine Miller. I try to offer you an starting location. Maps and information about through early October. Most trips will begin on a we will proceed to Allagash Lake. Several days experience that allows learning many camping this will be provided according to the trip Saturday or Sunday and “Maine” trips will can be spent at Allagash Lake, particularly if and canoeing skills. I find a complete experience selected. “Car pooling” and caravans are the begin at my house with transportation provided, the party is interested in quality fishing and is achieved when you help in gathering wood, norm. for up to 6 people. It is usually possible for the enjoying one of Maine’s most beautiful lakes. portaging, setting up camp and other normal trip remaining people to “truck pool” with a discount Next the group proceeds down 6 miles of duties. In short, I offer a trip with enjoyable to those who provide the vehicle. Allagash Stream to Chamberlain Lake and experiences plus valuable camping skills. By through Lock Dam to Eagle Lake, and finally using this approach, I am able to offer a reduced ending at Churchill Dam, after running the cost, and you go away with a greater sense of famous “Chase Rapids”.