Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penobscot Rivershed with Licensed Dischargers and Critical Salmon

0# North West Branch St John T11 R15 WELS T11 R17 WELS T11 R16 WELS T11 R14 WELS T11 R13 WELS T11 R12 WELS T11 R11 WELS T11 R10 WELS T11 R9 WELS T11 R8 WELS Aroostook River Oxbow Smith Farm DamXW St John River T11 R7 WELS Garfield Plt T11 R4 WELS Chapman Ashland Machias River Stream Carry Brook Chemquasabamticook Stream Squa Pan Stream XW Daaquam River XW Whitney Bk Dam Mars Hill Squa Pan Dam Burntland Stream DamXW Westfield Prestile Stream Presque Isle Stream FRESH WAY, INC Allagash River South Branch Machias River Big Ten Twp T10 R16 WELS T10 R15 WELS T10 R14 WELS T10 R13 WELS T10 R12 WELS T10 R11 WELS T10 R10 WELS T10 R9 WELS T10 R8 WELS 0# MARS HILL UTILITY DISTRICT T10 R3 WELS Water District Resevoir Dam T10 R7 WELS T10 R6 WELS Masardis Squapan Twp XW Mars Hill DamXW Mule Brook Penobscot RiverYosungs Lakeh DamXWed0# Southwest Branch St John Blackwater River West Branch Presque Isle Strea Allagash River North Branch Blackwater River East Branch Presque Isle Strea Blaine Churchill Lake DamXW Southwest Branch St John E Twp XW Robinson Dam Prestile Stream S Otter Brook L Saint Croix Stream Cox Patent E with Licensed Dischargers and W Snare Brook T9 R8 WELS 8 T9 R17 WELS T9 R16 WELS T9 R15 WELS T9 R14 WELS 1 T9 R12 WELS T9 R11 WELS T9 R10 WELS T9 R9 WELS Mooseleuk Stream Oxbow Plt R T9 R13 WELS Houlton Brook T9 R7 WELS Aroostook River T9 R4 WELS T9 R3 WELS 9 Chandler Stream Bridgewater T T9 R5 WELS TD R2 WELS Baker Branch Critical UmScolcus Stream lmon Habitat Overlay South Branch Russell Brook Aikens Brook West Branch Umcolcus Steam LaPomkeag Stream West Branch Umcolcus Stream Tie Camp Brook Soper Brook Beaver Brook Munsungan Stream S L T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp T8 R10 WELS East Branch Howe Brook E Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 WELS Bloody Brook Saint Croix Stream North Branch Meduxnekeag River W 9 Turner Brook Allagash Stream Millinocket Stream T8 R7 WELS T8 R6 WELS T8 R5 WELS Saint Croix Twp T8 R3 WELS 1 Monticello R Desolation Brook 8 St Francis Brook TC R2 WELS MONTICELLO HOUSING CORP. -

Finding Aid for MF180 Woods Music

ACCESSION SHEET Accession Number: 0001 Maine Folklife Center Accession Date: 1962.06.01 T# C# P D CD M A # Collection MF 076/ MF 180 # T Number: P S V D D Collection Maine / Maritimes # # # V A Name: Folklore Collection/ # # Woods Music Interviewer Margaret Adams Narrator: Various /Depositor: Description: 0001 Various, interviewed by Margaret Adams for CP 180, spring 1962, Houlton, Maine and Boiestown, New Brunswick. Folklore materials collected as a class project by Margaret Adams in Houlton, Maine, and Boiestown, New Brunswick. Accession includes typewritten stories, songs, jokes, and legends. Songs include an untitled song (“In the Spring of ‘62”?), “The Letter Edged in Black,” “The Jones Boys,” “The Winter of ‘73” (“McCullom Camp”), and “On the Bridge at Avignon.” Tall tales deal with Tom McKee, a Civil War soldier, and a deer story. Forerunners tell of seeing unexplained lights, bad luck, and other happenings. One sheet lists beliefs. Tales and legends include the legend of the Buck Monument in Bucksport, several haunted house stories, a banshee, premonitions, several devil stories, a Frenchman’s joke about “God Lover Oil,” and a Lubec minister’s scheme for extracting gold from sea water. Text: 50 pp. paper Related Collections & Accessions Restrictions No release. Copyright retained by interviewer and interviewees and/or their heirs. X ACCESSION SHEET Accession Number: 0022 Maine Folklife Center Accession Date: 1962.05.00 T# C# P D CD M A # Collection MF 076/ MF 180 # T Number: P S V D D Collection Maine / Maritimes # # # V A Name: Folklore Collection/ # # Woods Music Interviewer Sara Brooks Narrator: Various /Depositor: Description: 0022 Various, interviewed by Sara Brooks for CP 180, spring 1962, Island Falls and Sherman Mills, Mills, Maine. -

Fish River Scenic Byway

Fish River Scenic Byway State Route 11 Aroostook County Corridor Management Plan St. John Valley Region of Northern Maine Prepared by: Prepared by: December 2006 Northern Maine Development Commission 11 West Presque Isle Road, PO Box 779 Caribou, Maine 04736 Phone: (207) 4988736 Toll Free in Maine: (800) 4278736 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary ...............................................................................................................................................................3 Why This Byway?...................................................................................................................................................5 Importance of the Byway ...................................................................................................................................5 What’s it Like?...............................................................................................................................................6 Historic and Cultural Resources .....................................................................................................................9 Recreational Resources ............................................................................................................................... 10 A Vision for the Fish River Scenic Byway Corridor................................................................................................ 15 Goals, Objectives and Strategies......................................................................................................................... -

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920

Flood Frequency Analyses for New Brunswick Rivers Aucoin, F., D. Caissie, N. El-Jabi and N. Turkkan Department of Fisheries and Oceans Gulf Region Oceans and Science Branch Diadromous Fish Section P.O. Box 5030, Moncton, NB, E1C 9B6 2011 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2920 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. Technical reports are directed primarily toward a worldwide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Directorate Technical Reports. Numbers 715-924 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 925. Rapport technique canadien des sciences halieutiques et aquatiques Les rapports techniques contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui ne sont pas normalement appropriés pour la publication dans un journal scientifique. -

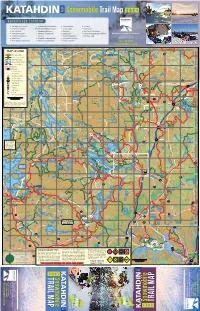

Snowmobile Trail Map 2021

KATAHDIN AREA Snowmobile Trail Map 2021 ADVERTISER LOCATOR 1 The Nature Conservancy 8 Katahdin Federal Credit Union 14 Shin Pond Village 21 Scootic In 2 Katahdin Inn & Suites Millinocket Memorial Hospital 15 5 Lakes Lodge 22 Libby Camps 3 Baxter Park Inn 9 Matagamon Wilderness 16 Flatlanders 23 River Driver’s Restaurant 4 Pamola Motor Lodge 10 Raymond’s Country Store 17 Bowlin Lodge 24 Friends of Katahdin Woods & Waters Katahdin Area Chamber of Commerce 1029 Central Street 5 Katahdin General Store 11 Chester’s 18 Katahdin Valley Motel 25 Mt. Chase Lodge Millinocket, ME 04462 6 Baxter Place 12 Brownville Snowmobile Club 19 Chesuncook Lake House 7 New England Outdoor Center 13 Wildwoods Trailside Cabins 20 Lennie’s Superette 207-723-4443 KatahdinMaine.com Advertiser List 1 New England Outdoor CenterO Eagle Advertiser List xbow Rd 470000 480000 490000 500000 2 Katahdin510000 Inn & Suites 520000 530000 540000 550000 ITS 560000 570000 Allagash Lake J o 1 New England Outdoor Center 5130000 h 3 Baxter Park Inn 86 Lake d 5130000 n m R s kha Advertiser 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola List Inn Lodge& Suites MAP LEGEND B Haymock Pin Millinocket r id Lake 1 New 3 BaxterEngland Park Outdoor Inn Center Li 71D g Lake 5 Kathdin General Store22 bb e y Pinnac Rd 2 Katahdin 4 Pamola Inn Lodge& Suites le Grand ITS 6 Katahdin Federal Credit Union Lo 11 TO THE o Lake Umcolcus 83 ITS Corridor Trails 3 Baxter 5 Kathdin 7Park Raymond’s Inn General Store TRAINS p Seboeis Lake 4 Pamola 6 Katahdin 8 Lodge Wildwoods Federal TrailsideCredit Union Millimagassett 3A Groomed Local Club Tr. -

STATE of MAINE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT STATE PLANNIJ'\G OFFICE 38 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 043 3 3-003Fi ANGUS S

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) Great Pond Tasl< Force Final Report KF 5570 March 1999 .Z99 Prepared by Maine State Planning Office I 84 ·State Street Augusta, Maine 04333 Acknowledgments The Great Pond Task Force thanks Hank Tyler and Mark DesMeules for the staffing they provided to the Task Force. Aline Lachance provided secretarial support for the Task Force. The Final Report was written by Hank Tyler. Principal editing was done by Mark DesMeules. Those offering additional editorial and layout assistance/input include: Jenny Ruffing Begin and Liz Brown. Kevin Boyle, Jennifer Schuetz and JefferyS. Kahl of the University of Maine prepared the economic study, Great Ponds Play an Integral Role in Maine's Economy. Frank O'Hara of Planning Decisions prepared the Executive Summary. Larry Harwood, Office of GIS, prepared the maps. In particular, the Great Pond Task Force appreciates the effort made by all who participated in the public comment phase of the project. D.D.Tyler donated the artwork of a Common Loon (Gavia immer). Copyright Diana Dee Tyler, 1984. STATE OF MAINE EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT STATE PLANNIJ'\G OFFICE 38 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 043 3 3-003fi ANGUS S. KING, JR. EVAN D. RICHERT, AICP GOVERNOR DIRECTOR March 1999 Dear Land & Water Resources Council: Maine citizens have spoken loud and clear to the Great Pond Task Force about the problems confronting Maine's lakes and ponds. -

Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’S Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1-2018 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake William W. Geller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Geller, William W., "Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps - Chapter 08: Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou Up the West Branch to Ripogenous Lake" (2018). Maine History Documents. 135. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/135 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Within Katahdin’s Realm: Log Drives and Sporting Camps Part 2 Sporting Camps Introduction The Beginning of the Sporting Camp Era Chapter 8 Fisk’s Hotel at Nicatou up the West Branch to Ripogenus Lake Pre-1894: Camps and People Post-1894: Nicatou to North Twin Dam Post-1894: Norcross Community Post-1894: Camps on the Lower Chain Lakes On the River: Ambajejus Falls to Ripogenus Dam At Ambajejus Lake At Passamagamet Falls At Debsconeag Deadwater At First and Second Debsconeag Lakes At Hurd Pond At Daisey Pond At Debsconeag Falls At Pockwockamus Deadwater At Abol and Katahdin Streams At Foss and Knowlton Pond At Nesowadnehunk Stream At the Big Eddy At Ripogenus Lake Outlet January 2018 William (Bill) W. -

Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Allagash Wilderness Waterway A Natural History Guide Lower Allagash River Below Allagash Falls by Sheila and Dean Bennett Bureau of Parks and Lands MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION All photographs © 1994 by Dean Bennett. Used by permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS TO THE VISITOR……………...……….………………..2 MAP AND MAP KEY …………..….………….…………3 INTRODUCTION …….………...………………………..4 THE LAND ………………………………………………..5 Bedrock ………………….……...................................5 Fossils ………………….……………………………..5 Ice Cave ……………….……………………………...5 Glacial Features ……….………………………….…6 THE WATERS …………….…………………………..….7 Allagash Lake…………………………………….…..7 Allagash Stream ………………………………….….8 Eagle Lake …………………………….……………..9 Churchill Lake ……………………….…………….10 Allagash River………………………….………...…11 WETLANDS ……………………………………….……12 Allagash Bogs ………………………………….…...12 Umsaskis Meadows ……………………………...…13 Shore Habitats …………………………………..…14 FORESTS AND FLOWERS ………………………..…..14 Spruce-Fir Forest ………………………………….15 Northern Hardwood Forest …………………….…15 Bog Forest ……………………………………….….16 Northern Swamp Forest ………………………..….16 Northern Riverine Forest ……………………..…..16 Old-Growth Forests ……….…………………….…16 NON_FLOWERING PLANTS ……………………..…..18 Ferns ……………………………………..………….18 Clubmosses……………………………….…………18 Horsetails ……………………………………..…..18 Mosses ..……………………………………….….…18 Lichens ……………………………………….….….18 Fungi ………………………………………….…….19 ANIMALS ………………………………………….……19 Mammals ………………………………………..….20 Birds ……………………………………………..….21 Reptiles and Amphibians ……………………...…..23 Fish …………………………………………….……24 Invertebrates ……………................................…….25 -

A Agash the Allagash and the St

THE ensure that this area will forever remain a place of you, your family, and friends will enjoy the memories of solace and refuge. your visit for a lifetime. A agash The Allagash and the St. John Rivers are deeply Sincerely, WILDERNESS W A TE RW A Y ingrained in the heritage of the communities of THE northern Maine. Mountains, rivers, and the ocean coastline are a crucial part of the history and economy of communities throughout the state. A visit to these John E. Baldacci Welcome communities will help you gain a better appreciation for Governor Maine’s unique history. You may learn, as well, of the Welcome to the Allagash Wilderness Waterway. For importance of our natural resources today, in our past, many visitors the Allagash Wilderness Waterway and in our future. MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION shines the brightest among the jewels of Maine’s BUREAU OF PARKS AND LANDS forty-seven state parks and historic sites. The No matter if a visit to the Allagash Wilderness Northern Region Office A agash Waterway has been praised and enjoyed as a Waterway is your first experience of a publicly-owned 106 Hogan Road sportsman's paradise for decades. The people of Maine outdoor place or the culmination of a lifetime of Bangor, Maine 04401 Maine made the dream of a protected Allagash River enjoyment of our state parks, it is a special experience. 207-941-4014 WILDERNESS WATERWAY poss ble. The State of Maine, through the Department In my visits to our state-owned lands, I have found www.maine.gov/doc/parks of Conservation’s Bureau of Parks and Lands seeks to something special about each of them. -

Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Part Two: Heritage Resource Assessment HERITAGE RESOURCE ASSESSMENT 24 | C h a p t e r 3 3. ALLAGASH HERITAGE RESOURCES Historic and cultural resources help us understand past human interaction with the Allagash watershed, and create a sense of time and place for those who enjoy the lands and waters of the Waterway. Today, places, objects, and ideas associated with the Allagash create and maintain connections, both for visitors who journey along the river and lakes, and those who appreciate the Allagash Wilderness Waterway from afar. Those connections are expressed in what was created by those who came before, what they preserved, and what they honored—all reflections of how they acted and what they believed (Heyman, 2002). The historic and cultural resources of the Waterway help people learn, not only from their forebears, but from people of other traditions too. “Cultural resources constitute a unique medium through which all people, regardless of background, can see themselves and the rest of the world from a new point of view” (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998, p. 49529). What are these “resources” that pique curiosity, transmit meaning about historical events, and appeal to a person’s aesthetic sense? Some are so common as to go unnoticed—for example, the natural settings that are woven into how Mainers think of nature and how others think of Maine. Other, more apparent resources take many forms—buildings, material objects of all kinds, literature, features from recent and ancient history, photographs, folklore, and more (Heyman, 2002). The term “heritage resources” conveys the breadth of these resources, and I use it in Storied Lands & Waters interchangeably with “historic and cultural resources.” Storied Lands & Waters is neither a history of the Waterway nor the properties, landscapes, structures, objects, and other resources presented in chapter 3. -

THE RANGELEY LAKES, Me to Play a Joke on a Fellow Woods Moose Yards Last Winter, Two of Them I Via the POR TLAND & RUM FORD FALLS RY

VOL. XXVII. NO. 8. PHILLIPS, MAINE, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1904. PRICE 3 CTS SPORTSMEN’S SUPPLIES Fish and Game Oddities. Tilden And Thd Trout An an jdote about a dogfish aalhisuu- sucoessful interview with the President published in a recent number of Hamper's Weekly, leads a correspondent of that paper to recall another incideut in which the late Samuel J. Tiidea was the chief figure. Mr. Tilden and W. M Evarts were walking one day along the v METALLIC CARTRIDGES banks of the Ammonoosac, in the White Mountains, when they espied a Never misfire. A Winchester .44, a Remington .30 30, a Marlin fish a few feet from the shore. “ I think .38 55, a S.evens .22 or any gun you may use always does Superior l 11 have that big trout,” said Mr. Tild Take-Down Reheating Shotguns The notion that one must pay from fifty dollars upwards in order to get Shooting -vitti U. M. C. Car. ridges. We make ammunition for en. “ How do you expect to catch him a good shotgun has been pretty effectively dispelled since the advent of every gun in the world and always of the same quality— U. M. C. without a hook?’’ exclaimed his com the Winchester Repeating Shotgun. These guns are sold within reach quality. panion. “ Wait and sec,” was the reply of almost everybody’s purse. They are safe, strong, reliable and handy. and, removing his coat and vest, he The Union fletailic Cartridge Cq., W hen it comes to shooting qualities no gun made beats them. -

ALLAGASH MAINE BUREAU of PARKS and LANDS WILDERNESS the Northward Natural Flow of Allagash Waters from Telos Lake to the St

ALLAGASH AND LANDS MAINE BUREAU OF PARKS WILDERNESS The northward natural flow of Allagash waters from Telos Lake to the St. John River presented a challenge to Bangor landowners and inves- WATERWAY tors who wanted to float logs from land around Chamberlain and Telos By Matthew LaRoche lakes southward to mills along the Penobscot River. So, they reversed the flow by building two dams in 1841. magnificent 92-mile-long ribbon of interconnected lakes, CHURCHILL DAM raised the water ponds, rivers, and streams flowing through the heart of MAHOOSUC GUIDE SERVICE level and Telos Dam controlled the Maine’s vast northern forest, the Allagash Wilderness water release and logs down Webster Waterway (AWW) features unbroken shoreline on the Stream and eventually to Bangor. headwater lakes and free-flowing river along the lower Chamberlain Dam was later modified waterway. The AWW’s rich culture includes use by to include a lock system so that logs Indigenous people for millennia and a colorful logging history. cut near Eagle Lake could be floated to the Bangor lumber market. In 1966, the Maine Legislature established the AWW to preserve, The AWW provides visitors with a true wilderness experience, with limited protect, and enhance this unique area’s wilderness character. vehicle access and restrictions on motorized watercraft. Some 100 primitive Four years later, the AWW garnered designation as a wild river campsites dot the shorelines, and anglers from all over New England come to LAROCHE MATT THE TRAMWAY HISTORIC in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSR). This the waterway in the spring and fall to fish for native brook trout, whitefish, and DISTRICT, which is listed on the year marks 50 years of federal protection under the NWSR Act.