Education in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pilot Study on the Perception of the Society Towards the Federal Constitution from the Aspect of Racial Unity

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No. 11, Nov, 2018, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2018 HRMARS The Pilot Study on the Perception of the Society towards the Federal Constitution from the Aspect of Racial Unity Fairojibanu, Nazri Muslim, Abdul Latif Samian To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i11/4899 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i11/4899 Received: 16 Oct 2018, Revised: 02 Nov 2018, Accepted: 16 Nov 2018 Published Online: 26 Nov 2018 In-Text Citation: (Fairojibanu, Muslim, & Samian, 2018) To Cite this Article: Fairojibanu, Muslim, N., & Samian, A. L. (2018). The Pilot Study on the Perception of the Society towards the Federal Constitution from the Aspect of Racial Unity. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(11), 273–284. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 8, No. 11, 2018, Pg. 273 - 284 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 273 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Malaysian Culture: Views of Educated Youths About Our Way Forward

ISBN 978-1-84626-xxx-x Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences Phnom Penh, Cambodia , September 28 - 29 , 2012, pp . xxx-xxx Malaysian Culture: Views of Educated Youths About Our Way Forward P.F. Chiok 1, C.C. Low 2, and S.M. Ang 1+++ 1Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (MALAYSIA), 2 University of Melbourne (AUSTRALIA) Abstract. A study was conducted amongst Malaysian university students who study locally and abroad to understand their views about the important elements of an emerging Malaysian culture. Ethnic cultures, national culture and global culture play different but unique roles in the formation of the Malaysian national identity. It is of academic interests to examine how the young generations of Malaysians are reconciling with the competing yet accommodating elements of the different ethnic cultures in the country. This paper is written with two main objectives: 1) to find out the students’ perspectives of the top elements that should make up a Malaysian culture and 2) to examine their view on ‘global culture’ and its roles in enriching the Malaysian culture as our national culture. The authors suggest that young Malaysians are optimistic about the emerging Malaysian culture and are adapting well to the cultural elements of other ethnic groups despite some differences in opinions about what constituted the Malaysian culture. Keywords: ethnic culture, Malaysian Culture, national culture, global culture, the Malaysian national identity 1. Introduction The National Culture Policy has always been associated with the goal of nation-building. Awareness already exists amongst young Malaysians with tertiary education that nation-building sometimes entails sacrifices, and fears of the unknown. -

SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES Rukun Negara As a Preamble to Malaysian Constitution

Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. & Hum. 29 (S2): 29 - 42 (2021) SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES Journal homepage: http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/ Rukun Negara as a Preamble to Malaysian Constitution Noor‘Ashikin Hamid*, Hussain Yusri Zawawi, Mahamad Naser Disa and Ahmad Zafry Mohamad Tahir Department of Law, Faculty of Law and International Relations, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kampung Gong Badak, 21300 Kuala Nerus, Terengganu, Malaysia ABSTRACT Rukun Negara is the Malaysian declaration of national philosophy drafted by the National Consultative Council and launched on 31st August 1970. The Rukun Negara aspires to establish a substantial unity of a nation. The principles in the Rukun Negara serve as an integrative key to harmonious and unity of the people in ensuring Malaysia’s success and stability. To realize the aspiration above, five (5) principles are presented, namely the “Belief in God”; “Loyalty to the King and Country”; “Supremacy of the Constitution”; “Rules of Law”; and “Courtesy and Morality.” However, there is a postulation that Rukun Negara’s inclusion as a preamble may undermine constitutional supremacy. Therefore, this paper is aimed to enlighten the matter via critical interpretation of the principles and examination of related cases in Malaysia. The conducted analyses showed that the Federal Constitution per se is sufficient and comprehensive to address the conflicting issues. Despite some ambiguities probed in the Constitution, its supremacy is still fully preserved and effective without including Rukun Negara as the preamble. Keywords: Constitution, five principles, preamble,Rukun Negara INTRODUCTION ARTICLE INFO The British occupation of Malaya had Article history: Received: 2 May 2020 brought the “divide and rule” policy that Accepted: 12 March 2021 Published: 17 May 2021 separated different races into different forms of social, educational, and economic DOI: https://doi.org/10.47836/pjssh.29.S2.03 settings. -

Between Stereotype and Reality of the Ethnic Groups in Malaysia

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 16, Youth and Community Wellbeing: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for Empowerment V2. 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Images in the Human Mind: Between Stereotype and Reality of the Ethnic Groups in Malaysia Rohaizahtulamni Radzlan, Mohd Roslan Rosnon & Jamilah Shaari To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i16/9020 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i16/9020 Received: 24 October 2020, Revised: 18 November 2020, Accepted: 30 November 2020 Published Online: 17 December 2020 In-Text Citation: (Radzlan et al., 2020) To Cite this Article: Radzlan, R., Rosnon, M. R., & Shaari, J. (2020). Images in the Human Mind: Between Stereotype and Reality of the Ethnic Groups in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(16), 412–422. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Special Issue: Youth and Community Wellbeing: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for Empowerment V2, 2020, Pg. 412 - 422 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 412 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

1 the CONCEPT of 1MALAYSIA from ISLAMIC PERSPECTIVES Amini Amir ABDULLAH Universiti Putra Malaysia Faculty of Human Ecology, De

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITY STUDIES Vol 2, No 2, 2010 ISSN: 1309-8063 (Online) THE CONCEPT OF 1MALAYSIA FROM ISLAMIC PERSPECTIVES Amini Amir ABDULLAH Universiti Putra Malaysia Faculty of Human Ecology, Department of Nationhood (Government) and Civilization Studies 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Shamsuddin MONER Malaysian Da’wah Council of Malaysia (YADIM) Bahagian Dakwah Profesional YADIM, Tingkat Bangunan Tabung Haji, No, 28, Jalan Rahmat Off Jalan Ipoh, 50350 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Datuk Aziz Jamaludin Mhd TAHIR Malaysian Da’wah Council of Malaysia Yayasan Dakwah Islamiah Malaysia (YADIM), Kompleks Pusat Islam, Jalan Perdana, 50480 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The 1Malaysia concept (People First, Performance Now) is a vision introduced by the sixth Malaysian Prime Minister YAB. Datuk Seri Mohd. Najib Tun Abdul Razak on 3rd of April 2009 soon after his sworn-in ceremony. The 1Malaysia concept protects the rights of all ethnic groups in the country and is able to bring Malaysia forward. The concept of 1Malaysia does not stray a single inch from the provisions of the Federal Constitution or the Rukun Negara (Five Pillars of the nation). The opposition parties claimed that they have introduced earlier the so called Middle Malaysia vision (originally from their Malaysian Malaysia slogan). Actually they were worried that the 1Malaysia concept has been accepted by most ethnic groups in Malaysia and there was a renewed spirit among the people to bring the country to greater heights. The government wants the Malaysian people to adopt the attitude of acceptance instead of tolerance. -

Bab Ii Pendekatan Keamanan Sektor Politik Yang

BAB II PENDEKATAN KEAMANAN SEKTOR POLITIK YANG MEMPENGARUHI KEBIJAKAN MALAYSIA DI PELABUHAN JOHOR Bab ini akan menjelaskan apa yang mempengaruhi kebijakan yang dibuat oleh pemerintah Malaysia pada masa Mahathir Mohamad kembali naik menjadi Perdana Menteri melalui pendekatan konsep milik Buzan dkk. Buzan dkk bahwa sektor politik lebih menekankan kedaulatan negara yang mana ada dalam agenda militer sesuai dengan ancamannya. Tetapi, karena sektor militer memiliki bagian tersendiri, sektor politik lebih terfokus terhadap ancaman non-militer (Buzan, Waever, & de Wilde, 1998, hal. 140-143). Dalam hal ini, Malaysia sebagai aktor politik merasa memiliki kepentingan nasional yang harus dicapai. Kedaulatan wilayah menjadi keutamaan untuk memperoleh kekuasaan yang absolut. Pelabuhan Johor merupakan wilayah strategis yang terletak di Selat Johor. Selat tersebut merupakan jalur perdagangan Malaysia. Dengan adanya kebijakan tersebut, tentunya menjadi sebuah keuntungan bagi Malaysia dalam lalu lintas perdagangan serta luas wilayah bertambah. 29 Dimulai dengan negara berdaulat, yang membentuk sebagian besar sektor politik, kita dapat melihat masalah ancaman dan kerentanan melalui argumen bahwa suatu negara terdiri dari tiga komponen: ideologi, bentuk fisik, dan institusi. Mengurangi masalah-masalah yang masuk ke dalam sektor lain(sebagian besar ancaman yang dibuat langsung dalam bentuk fisik harus militer, ekonomi atau lingkungan), kita dibiarkan dengan ideologi(kecuali identitas ideologi independen dari institusi) dan institusi sebagai pertanyaan dari ideologi di mana lembaga-lembaga politik dibangun (Buzan, Waever, & de Wilde, 1998, hal. 150-151). Ideologi yang dimiliki negara secara bersama adalah bersifat nasionalisme, terutama nasionalisme sipil tetapi kadang-kadang ethno- nasionalisme dan ideologi politik. Dengan mengancam suatu ideologi, seseorang dapat mengancam stabilitas tatanan politik (Buzan, Waever, & de Wilde, 1998, hal. -

Identity Politics and Young-Adult Malaysian Muslims

Eras Edition 12, Issue 1, December 2010 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/publications/eras Identity Politics and Young-Adult Malaysian Muslims Dahlia Martin (Flinders University, Australia) Abstract: A rivalry between political parties has meant that the position of religion in Malaysia is very much tied in with nationalistic politics. Having been in power since the country’s independence, the United Malays Nationalist Organisation (UMNO) of the Barisan Nasional (National Front) has attempted, through use of several national ideologies and discourses, to propagate a Malay Muslim hegemony within a multiethnic framework. The most obvious result of this is the categorization of the Malaysian population by ethnicity in all facets of their lives. Another consequence is the precarious position of young adults in Malaysia: the government expects much of Malaysian youth, especially Muslim youth, yet ironically, their inadequate representation and vulnerability to authoritative depictions has left them a marginalized group. This article looks at the discourses concerning young-adult Malaysian Muslims, and, through in- depth interviews with a small sample of urban youth, attempts to uncover what discourses young-adult Malaysian Muslims are actually using in their everyday lives. My findings point to a transcendence of religion over race amongst most young Muslims, with there being much discomfort over assuming the ethnic identity marker of ‘Malay’. In the Southeast Asian country of Malaysia, the position of Islam in public life is very much linked with national politics. The United Malays Nationalist Organisation (UMNO), the Malay race-based and largest party in the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN), or National Front coalition, has, for decades now, been locked in a rivalry with the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) over command of the Muslim-Malay electorate. -

Perluasan Dan Pengukuhan Aktiviti Kelab Rukun Negara

JABATAN PERPADUAN NEGARA KEMENTERIAN PENGAJIAN TINGGI DAN INTEGRASI NASIONAL MALAYSIA JABATAN PERDANA MENTERI PANDUAN PENGURUSAN SEKRETARIAT RUKUN NEGARA DI INSTITUSI PENGAJIAN TINGGI Rukun Negara Pengisytiharan BAHAWASANYA NEGARA KITA MALAYSIA mendukung cita-cita hendak mencapai perpaduan yang lebih erat di kalangan seluruh masyarakatnya; memelihara satu cara hidup demokratik; mencipta satu masyarakat yang adil di mana kemakmuran Negara akan dapat dinikmati bersama secara adil dan saksama; menjamin satu cara yang liberal terhadap tradisi-tradisi kebudayaannya yang kaya dan berbagai corak; membina satu masyarakat progresif yang akan menggunakan sains dan teknologi moden; MAKA KAMI, Rakyat Malaysia, berikrar akan menumpukan seluruh tenaga dan usaha kami untuk mencapai cita-cita tersebut berdasarkan atas prinsip-prinsip yang berikut: KEPERCAYAAN KEPADA TUHAN KESETIAAN KEPADA RAJA DAN NEGARA KELUHURAN PERLEMBAGAAN KEDAULATAN UNDANG-UNDANG KESOPANAN DAN KESUSILAAN 2 PANDUAN PENGURUSAN SEKRETARIAT RUKUN NEGARA DI INSTITUSI PENGAJIAN TINGGI 1. PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Peristiwa rusuhan kaum/etnik pada 13 Mei 1969 telah mengganggugugat keamanan dan kestabilan negara pada ketika itu dan tindakan serta merta telah diambil untuk mengisytiharkan darurat di seluruh negara. Dengan pengisytiharan tersebut, sistem kerajaan berparlimen telah digantung dan seterusnya Majlis Gerakan Negara (MAGERAN) telah ditubuhkan untuk mengembalikan keamanan, menegakkan semula undang-undang negara serta memupuk suasana harmoni dan percaya mempercayai di kalangan rakyat. 1.2 -

4 Smart City: the New Frontier of Innovation

Contents ISSUE 13 COVER STORY 4 Smart City: The New Frontier of Innovation PERSONALITY 4 12 Maszni Abdul Aziz Keeping The Craft Of Making Beaded Shoes Alive FEatURES 14 KL Converge! 2015 18 Malaysia Joins Regional Community In Launching ICT Volunteer Programme 12 14 23 Competition In Broadcasting Heats Up 27 Mobile Payments As Standard Bearer For Digital Services 33 Extending Postal Services In The Name Of Tourism And Country 36 Raising Good Digital Citizens Through Klik Dengan Bijak® Programme 18 41 Getting Ready For Digital Terrestrial TV 45 Kemaman Smart Community 50 Communications And Multimedia Industry Landscape: Looking Ahead 55 How Retail Is Being Transformed By 33 The Internet Of Things REGULARS 58 Gallery 60 Notes From All Over 62 Kaleidoscope 64 Scoreboard 36 From the Chairman's Desk Warmest greetings. Advisor Dato’ Sri Dr Halim Shafie Chairman, Malaysian Communications It is my great pleasure to extend greetings to readers of .myConvergence. and Multimedia Commission In-house Consultant The cover story on smart city is very apt for this magazine given that smart cities Toh Swee Hoe are created through the convergence of many technologies, services, applications Editor and policies. All over the world planners are working towards turning cities into Ahmad Nasruddin Atiqullah Fakrullah smart cities. Editorial Board Eneng Faridah Iskandar This is no small task as the benefits of implementing smart city technologies Faizah Zainal Abidin and services impact millions of residents of those cities. Immense resources are Harme Mohamed needed for implementation of any smart city framework, making it vital that the Markus Lim Han King Mohd Zaidi Abdul Karim framework and implementation of such projects are done right. -

AE-Timeline I

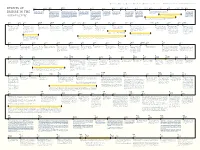

T Tom Roberts J Jamini Roy U U Ba Nyan L Lim Cheng Hoe C Chuah Thean Teng A Awang Sitai To find out more about these artists, refer to “Six Artists' Lives and Legacies.” 1600 1757 1764 1767 1769 1770 1773 1774 1786 EVENTS OF 1577 1580 1591 1716 1775 1780 1782 1783 1784 Sir Francis Drake is the first Sir James Lancaster and George Queen Elizabeth I grants a royal charter to the newly Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar e EIC defeats Siraj-ud-daula, e EIC defeats allied In the First Anglo-Mysore James Cook, an English e EIC’s administration In the First Anglo-Maratha War against the Maratha Empire, In exchange for British Englishman to make contact with Raymond embark upon a voyage to founded East India Company (EIC) to pursue trade in establishes a decree giving the EIC the ruling Nawab of Bengal, and Mughal, Bengal and Oudh War, Mysorean forces defeat naval lieutenant, sails and of Madras and Bombay the British fail to retain any significant territorial gains in the military assistance against the Spice Islands during his the East Indies with the approval of the East Indies. e Dutch Vereenidge Oost-Indische rights to duty-free trade in India. his French allies at the Battle of forces at the Battle of Buxar. the combined armies of the maps the eastern coast of becomes subordinate to Indian subcontinent. Siam, the Sultan of Kedah EMPIRE IN THE circumnavigation of the globe. Queen Elizabeth I. Lancaster Compagnie, or United East India Company, is founded e EIC had earlier set up factories Plassey. -

The Malaysian Albatross of May 13, 1969 Racial Riots

The Malaysian Albatross of May 13, 1969 Racial Riots Malachi Edwin VETHAMANI University of Nottingham Malaysia1 Introduction RACIAL riots in Malaysia are an uncommon phenomenon though there is a constant reminder and threat that the 13 May 1969 riots could recur. The 13 May, 1969 racial riots remains a deep scar in the nation’s psyche even today and the fear of such a re- occurrence continues to loom especially when some unscrupulous Malay politicians remind the nation that such an eventuality is a possibility if the privileged position of Malays is threatened. Yet, Malaysia has prided itself as a model for multi-cultural and multi-racial harmony in its sixty over years of existence as a nation. However, its attempts at forging a Malaysian race of “Bangsa Malaysia” (Mahathir 1992: 1) has not been achieved. In recent post-colonial nations, especially in nations with mixed populations like Malaysia, a lot of effort is put into projecting a national culture or a national identity. This attempt to forge various races into a single cultural entity is an impossibility, and it is a misconception that there can be a single national culture. As Ahmad says, any nation comprises cultures not just one culture. He asserts that it is a mistaken notion that “each ‘nation’ of the ‘Third World’ has a ‘culture’ and a ‘tradition’” (9). This paper examines Malaysian writers’ creative response in the English language to the 13 May, 1969 riots. It presents a brief historical context to the violent event and political response to the event which has resulted in the passing of various policies and laws that has impacted not only on the re-structuring of Malaysian society but also the management of the relationships among the multi-ethnic communities in the country. -

The Implementation of History Curriculum in Primary School with Environmental Influence and Knowledge in Enforcing Self-Identity As a Malaysian

https://series.gci.or.id Global Conferences Series: Social Sciences, Education and Humanities (GCSSSEH), Volume 2, 2019 The 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Development & Multi-Ethnic Society DOI: https://doi.org/10.32698/GCS.01114 The Implementation of History Curriculum in Primary School with Environmental Influence and Knowledge in Enforcing Self-Identity as a Malaysian Zunaida Zakaria1, Abdul Razaq Bin Ahmad2 & Mohd Mahzan Awang3 1 Ministry of Education, MALAYSIA 23 Faculty of Education, The National University of Malaysia, MALAYSIA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper discusses the implementation of the primary school history curriculum with the support of the environment and knowledge to realize the nation's aspirations, especially in promoting Malaysian self- identity among primary school students. The implementation of this primary school history curriculum is supported by the availability of infrastructure, management administration, content knowledge and pedagogy as well as history-based thinking skills assessed from the teacher's perspective. The implementation of this primary school history curriculum is evaluated on the aspects of effective history teaching methods, the use of textbooks, teaching aids where the assessment in this study involving both teachers and students. In addition, the self-identity practice as a Malaysian was assessed from the perspective of students for aspects comprises of understanding human behaviour, actions and consequences in history, the uniqueness of our homeland, glory and patriotic citizens as well as understanding of democratic practices. History subjects have become a core subject that all students must learn in the Primary School Curriculum from year 4 in the second grade. The role of this history subject is to underpin and nurture students’ patriotic souls with their knowledge on historical values.