A Biblical Perspective on Migration: One History, One Solution 121 Gyula Homoki: Where to Look in Suffering? a Fictional Round-Table Discussion with J.B., J.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Not Rescind the 1521 Excommunication of Luther?

From Conflict to Communion: Why not rescind the 1521 excommunication of Luther? The point of lifting personal excommunications posthumously is not for the repose of the souls of the excommunicated. It is to take away the public rejection of that person and the scandal caused by the condemnation. The following material is a chapter from the article, “From Conflict to Communion: Going Home to Rome,” which addresses various issues in the LWF/Vatican report From Conflict to Communion (C2C). C2C purports to be a candid look at where things stand between Lutherans and Roman Catholics. In fact C2C has an agenda: It directs Lutherans to be PC so that in time they can be RC. The full article includes the following chapters: 1. Lutherans and Catholics agree/disagree on baptism. 2. C2C declares JDDJ has the “highest level of authority.” (¶97) 3. Justification must decrease so that unity may increase. 4. C2C conceals the Catholic rejection of “faith alone.” 5. C2C’s focus on “Luther’s theology” disguises a caricature of Luther. 6. Why not rescind the 1521 excommunication of Luther? 7. C2C creates a caricature of Luther on scripture by omitting its gospel center. 8. C2C hides the Vatican view: Lutherans are not really, truly “Church.” 9. C2C assumes papal primacy and infallibility are inevitable. 10. Mary, Mary, why are they hiding you? 11. C2C glides over the ordination of women. 12. C2C kicks the can down the road: Lutherans must concede to unity on Rome’s terms. * * * * * 6. Why not rescind the 1521 excommunication of Luther? On June 15, 1520, Pope Leo X issued his bull, Exsurge Domine (“Arise, O Lord, and judge your cause….The wild boar from the forest seeks to destroy [the vineyard]”), threatening Luther, “the wild boar,” with excommunication. -

Confessio Im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- Und Fremdwahrnehmung in Der Frühen Neuzeit

Mona Garloff / Christian Volkmar Witt (Hg.) Confessio im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- und Fremdwahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit. Ein Studienbuch © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Abteilung für Abendländische Religionsgeschichte Herausgegeben von Irene Dingel Beiheft 129 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Confessio im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- und Fremdwahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit Ein Studienbuch Herausgegeben von Mona Garloff und Christian Volkmar Witt Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Die Publikation wurde gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über https://dnb.de abrufbar. © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen Dieses Material steht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 International. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz zu sehen, besuchen Sie http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/4.0/. Satz: Vanessa Weber, Mainz Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2197-1056 ISBN (Print) 978-3-525-57142-2 ISBN (OA) 978-3-666-57142-8 https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Inhalt Vorwort .............................................................................................................. 7 Christian V. Witt Wahrnehmung, Konflikt und Confessio. Eine Einleitung ........................ -

Die Bibelübersetzung Martin Luthers

TY3003 – Sprachwissenschaftlicher D-Aufsatz Björn Kinding – Högskolan Dalarna VT11 TY3003 – Sprachwissenschaftlicher D-Aufsatz Björn Kinding – Högskolan Dalarna VT11 DIE BIBELÜBERSETZUNG MARTIN LUTHERS: EINE SOZIOLINGUISTISCHE ANALYSE DER ABSICHT, DER METHODE UND DER AUSWIRKUNG - 1/87 - TY3003 – Sprachwissenschaftlicher D-Aufsatz Björn Kinding – Högskolan Dalarna VT11 Abstrakt Brundin (2004, S. 63) sagt, dass sich die Reformation „um einen Kampf handelte, der Auswirkungen auf die ganze gesellschaftliche Struktur hatte.“ Das Ziel dieser Arbeit ist die Absichten hinter, die linguistischen Methoden und die sozialen Auswirkungen der Bibelübersetzung Luthers festzustellen, und dadurch die Aussage Brundins zu bestätigen bzw. widerlegen. Es wurde gefunden, dass Martin Luther die Bibelübersetzung und die Reformation in enger Zusammenarbeit mit seinen Kollegen an der Leucorea Universität und unter Führung des sächsischen Kurfürsten, Friedrich III., durchgeführt hat. Dabei haben die verwendeten linguistischen Methoden eine Schlüsselrolle gespielt, und viele heute bekannten wissenschaftlichen Theorien sind praktisch umgesetzt worden. Dazu gehören die Sapir-Whorf-Hypothese, die Defizit- bzw. die Differenzhypothese und die Diskurstheorie. Die Reformation hat eine gewaltige Machtverschiebung zur Folge, wo der Klerus dem Adel viele Rechte abgeben müsste, und die neu erzeugte Sprache der Lutherbibel hat zu einer deutschen Einheitssprache und die Erstehung eines deutschen Nationalstaates geführt. Als Schlussergebnis kann die Aussage Brundins klar bestätigt -

Het Christendom Katholicisme

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/67918 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-04 and may be subject to change. R e l ig ie s in N e d e r l a n d HOOFDSTUK 5 HET CHRISTENDOM KATHOLICISME Erik Borgman en Marit Monteiro In Amerikaanse en Engelse films en televisieseries worden belijdende rooms-katho- lieken nogal eens verbeeld als mensen die ook de weerbarstiger kanten van wat geldt als de officiële leer van hun kerk, zeer serieus nemen. Vrouwen die niet willen scheiden van hun overspelige of gewelddadige echtgenoot, echtparen die een kind met een zware erfelijke ziekte welbewust geboren laten worden en levenslang ver zorgen als zware, maar heilige plicht. Bij wie nadenkt over de actuele situatie van het Nederlandse katholicisme, zullen dergelijke beelden niet snel opkomen. Ook onder Nederlandse katholieken komen vormen van toewijding voor die tot de ver beelding spreken. De in 2008 overleden jezuïet Jan van Kilsdonk gold bijvoorbeeld om zijn levenslange betrokkenheid bij moeilijk bereikbare groepen, sinds de jaren 1980 vooral aids-patiënten en HIV-geïnfecteerden, als 'pastor van Amsterdam'. Vanwege zijn inzet, door velen gewaardeerd als een authentieke pastorale betrok kenheid, werd hij in de hoofdstad op handen gedragen. Van Kilsdonk liet zichzelf duidelijk kennen als priester en religieus, maar cultiveerde tegelijkertijd een af stand tot tal van onderdelen van de katholieke leer. Precies deze ambivalentie te kent de houding die veel van zijn geloofsgenoten ten opzichte van de eigen kerk aannemen. -

Martin Luther Extended Timeline Session 1

TIMELINES: MARTIN LUTHER & CHRISTIAN HISTORY A. LUTHER the MAN (1483 – 1546) 1502: Receives B.A. at University of Erfurt 1505: Earns M.A. at Erfurt; begins to study law 1505 Luther “struck by lightning” and vows to become a monk 1505 Luther enters the Order of Augustinian Hermits 1507: Luther is ordained and celebrates his first Mass; he panics during the ceremony 1510: Luther visits Rome as representative of Augustinians 1511: Luther transfers to Wittenberg to teach at the new university. 1512: Luther earns his doctorate of theology 1513: Luther begins lecturing on The Psalms 1515: Luther lectures on Paul’s Epistles to the Romans 1517: October 31, he posts his “95 Theses (points to debate)” concerning indulgences on Wittenberg Church door. 1518: At meeting in Augsburg, Luther defends his theology & refuses to recant 1518: Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony places Luther under his protection. 1519: In debates with Professor John Eck at Leipzig, Luther denies supreme authority of popes and councils 1520: Papal bull (Exsurge Domine) gives Luther 60 days to recant or be excommunicated 1520: Luther burns the papal bull and writes 3 seminal documents: “To the Christian Nobility,” “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church,” & “The Freedom of a Christian” 1521: Luther is excommunicated by the papal bull Decet Romanum Pontificem 1521: He refuses to recant his writings at the Diet of Worms 1521: New HRE Charles V condemns Luther as heretic and outlaw Luther is “kidnapped” and hidden in Wartburg Castle Luther begins translating the New Testament -

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe Is Born in Yorkshire

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe is born in Yorkshire, England 1369?: Jan Hus, born in Husinec, Bohemia, early reformer and founder of Moravian Church 1384: John Wycliffe died in his parish, he and his followers made the first full English translation of the Bible 6 July 1415: Jan Hus arrested, imprisoned, tried and burned at the stake while attending the Council of Constance, followed one year later by his disciple Jerome. Both sang hymns as they died 11 November 1418: Martin V elected pope and Great Western Schism is ended 1444: Johannes Reuchlin is born, becomes the father of the study of Hebrew and Greek in Germany 21 September 1452: Girolamo Savonarola is born in Ferrara, Italy, is a Dominican friar at age 22 29 May 1453 Constantine is captured by Ottoman Turks, the end of the Byzantine Empire 1454?: Gütenberg Bible printed in Mainz, Germany by Johann Gütenberg 1463: Elector Fredrick III (the Wise) of Saxony is born (died in 1525) 1465 : Johannes Tetzel is born in Pirna, Saxony 1472: Lucas Cranach the Elder born in Kronach, later becomes court painter to Frederick the Wise 1480: Andreas Bodenstein (Karlstadt) is born, later to become a teacher at the University of Wittenberg where he became associated with Luther. Strong in his zeal, weak in judgment, he represented all the worst of the outer fringes of the Reformation 10 November 1483: Martin Luther born in Eisleben 11 November 1483: Luther baptized at St. Peter and St. Paul Church, Eisleben (St. Martin’s Day) 1 January 1484: Ulrich Zwingli the first great Swiss -

Die Einladung Martin Luthers Nach Salzburg Im Herbst 1518 127-159 © Gesellschaft Für Salzburger Landeskunde, Salzburg, Austria; Download Unter 127

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Mitt(h)eilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 151 Autor(en)/Author(s): Sallaberger Johann Artikel/Article: Die Einladung Martin Luthers nach Salzburg im Herbst 1518 127-159 © Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, Salzburg, Austria; download unter www.zobodat.at 127 Die Einladung Martin Luthers nach Salzburg im Herbst 1518 Von Johann Sallaberger Im Jahre 1556 erschien in Jena der erste Band einer Sammlung von Luther- Briefen, die der evangelische Theologe Johannes Aurifaber herausgab. Dieser war aus Sachsen gebürtig, hatte Luther gegen Ende seines Lebens als Famulus gedient und war auch bei dessen Tod in Eisleben am 18. Februar 1546 zugegen gewesen. Er galt als eifriger Sammler von Luther betreffenden Schriftstücken1. In diesem Band gedruckter Luther-Briefe findet sich auch ein nicht mehr im Original er haltenes Schreiben, das der damalige Vorgesetzte Luthers, Johann von Staupitz, am Fest „Kreuzerhöhung“ (14. September) des Jahres 1518 aus Salzburg an den Reformator richtete, in dem er Luther einlud, zu ihm zu kommen, um „mit ihm zusammen zu leben und zu sterben“ (ut simul vivamus moriamurque). Diese Ein ladung an Luther, nach Salzburg zu kommen, ausgesprochen noch während der Regierungszeit des bekannten Salzburger Erzbischofs Leonhard von Keutschach, dessen eindrucksvolles Denkmal und dessen sehenswerte Fürstenzimmer auf der Festung Hohensalzburg wohl allgemein bekannt sind, hat in der kirchlichen und profanen Geschichtsschreibung Salzburgs bisher wenig Beachtung gefunden2. Die folgende Studie möchte daher auf dieses interessante Schriftstück hinweisen und zugleich den Versuch unternehmen, die Hintergründe dieses Schreibens zu be leuchten. -

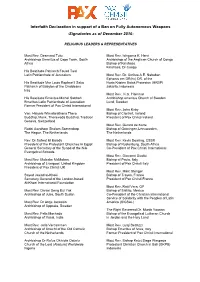

Interfaith Declaration in Support of a Ban on Fully Autonomous Weapons -Signatories As of December 2016

Interfaith Declaration in support of a Ban on Fully Autonomous Weapons -Signatories as of December 2016- RELIGIOUS LEADERS & REPRESENTATIVES Most Rev. Desmond Tutu Most Rev. Isingoma K. Henri Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town, South Archbishop of the Anglican Church of Congo Africa Bishop of Kinshasa Kinshasa, Dr Congo His Beatitude Patriarch Fouad Twal Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem Most Rev. Dr. Soritua A.E. Nababan Ephorus em DR(hc) DR. of the His Beatitude Mar Louis Raphael I Sako Huria Kristen Batak Protestan (HKBP) Patriarch of Babylon of the Chaldeans Jakarta, Indonesia Iraq Most Rev. K.G. Hammar His Beatitude Emeritus Michel Sabbah Archbishop emeritus Church of Sweden Emeritus Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem Lund, Sweden Former President of Pax Christi International Most Rev. John Kirby Ven. Halyale Wimalarathana Thero Bishop of Clonfert, Ireland Buddhist Monk, Therawada Buddhist Tradition President of Pax Christi Ireland Geneva, Switzerland Most Rev. Gerard de Korte Rabbi Awraham Shalom Soetendorp Bishop of Groningen-Leeuwarden, The Hague, The Netherlands The Netherlands Rev. Dr Safwat El Baiady Most Rev. Kevin Dowling, CSSR President of the Protestant Churches in Egypt Bishop of Rustenburg, South Africa General Secretary of the Synod of the Nile Co-President of Pax Christi International Evangelical Schools Most Rev. Giovanni Giudici Most Rev. Malcolm McMahon, Bishop of Pavia, Italy Archbishop of Liverpool, United Kingdom President of Pax Christi Italy President of Pax Christi UK Most Rev. Marc Stenger Sayed Jawad al-Khoei Bishop of Troyes, France Secretary General of the London-based President of Pax Christi France Al-Khoei International Foundation Most Rev. Raúl Vera, OP Most Rev. -

A Man Named Martin Part 1: the Man Session Three

A Man Named Martin Part 1: The Man Session Three Pope Leo X Pope Leo X: This article gives a biography of Pope Leo X, all that he was involved in, and why he needed so much money. The Medici Family: This article traces the history and powerful influence of the Medici family, of which Pope Leo X was a member. St. Peter's Basilica: This article gives the history of the basilica, from Peter’s martyrdom to its construction in Luther’s time. The Roman Catholic Church in the Late Middle Ages: This article describes the structure of the Roman Catholic Church, the various offices, and monastic movements. Indulgences Roman Teachings about Indulgences: DELTO (Distance Education Leading to Ordination) video with Dr. Paul Robinson (Church History 2, Volume 3). When did Indulgences Begin? DELTO (Distance Education Leading to Ordination) video with Dr. Paul Robinson (Church History 2, Volume 4). John Tetzel: This brief biography describes the Dominican monk who stirred Luther’s response to indulgences. How did Luther Come to Preach Against Indulgences?: DELTO (Distance Education Leading to Ordination) video with Dr. Paul Robinson (Church History 2, Volume 8). Image of an Indulgence: This is a link to an image of an indulgence. It is written in German, but you’ll recognize the signature of Johannes Tetzel. Frederick the Wise Heroes and Saints of the Reformation: Frederick the Wise (1463-1525): This article introduces us to Frederick the Wise. 1 Religious Relics Frederick the Wise boasted a collection of thousands of relics. Here are some links that provide more information about them: Top 10 Religious Relics: Time magazine looks at the lore and whereabouts of religious relics from Christianity, Buddhism and Islam. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds Life Without End the Bible's

IT IS WRITTEN: “How can they preach, unless they are sent?” (ROMANS 10:15) A PUBLICATION OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD The Bible’s ‘Prayer Book’ A walk through the CURRENT EVENTS Living in and Understanding our “Babylon” Psalms page 5 page 14 75TH ANNIVERSARY OF “THE SEM” The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds page 8 YOUNG BRANCHES Life Without End page 11 JANUARY– FEBRUARY 2021 FROM THE PRESIDENT: by REV. JOHN A. MOLDSTAD, President EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD, Mankato, Minn. HowVaporVapor Makes Plans Dear Members and Friends of our ELS: We know what happens when a glass of hot water is placed his ventures, and now he was doing even more expansion. outside on an icy morning. For a time, vapor rises when the When I interjected, “I guess the Lord has really blessed you,” heat meets the cold. Then it quickly disappears. That rising I could sense he felt momentarily uneasy. He did not speak vapor is used by the writer of James to have us reflect on at all of his accomplishments as gifts from God. He replied, the way we go about our lives in making plans. Planning for “Well, I don’t mean to be ‘brag-tocious’ but…” Then he quickly the new year – a year we pray will not repeat the pandemic launched into more of his lucrative plans. challenges of 2020 – needs always to consider what James wrote by inspiration of God the Holy Spirit: Now listen, you Could we also be guilty of the sin of boasting in a less obvious who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, way? Our sinful mind that we carry with us daily as unwanted spend a year there, carry on business and make money.” baggage tempts us to leave God out of the picture. -

Statement of Faith and Spiritual Leaders on The

Statement of Faith and Spiritual Leaders on the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP21 in Paris in December 2015 We raise our voices to the governments represented at COP21 in Paris to utilize the special momentum given on this highly significant occasion: COP21 provides a critical opportunity to benefit the whole of the human community. For the first time in over 20 years of UN negotiations, a global and comprehensive agreement on climate justice and climate protection – supported from all the nations of the world – can be reached. We as religious leaders: “stand together to express deep concern for the consequen- ces of climate change on the earth and its people, all entrusted, as our faiths reveal, to our common care. Climate change is indeed a threat to life. Life is a precious gift we have received and that we need to care for”1. Together we confirm: Our religious convictions and cosmological narratives tell us that this earth and the whole universe are gifts that we have received from the spring of life, from God. It is our obligation to respect, protect and sustain these gifts by all means. Therefore: COP21 is the right moment to translate ecological stewardship into concrete climate action. Our religious convictions and traditions tell us of the ethical rule of reciprocity: to treat others as we would like them to treat us. This includes future generations. It is our duty to leave this earth behind to our children and grandchildren to ensure sustainable and acceptable living conditions in future for all. Therefore: COP21 is the right moment for showing inter-generational responsibility.