Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Not Rescind the 1521 Excommunication of Luther?

From Conflict to Communion: Why not rescind the 1521 excommunication of Luther? The point of lifting personal excommunications posthumously is not for the repose of the souls of the excommunicated. It is to take away the public rejection of that person and the scandal caused by the condemnation. The following material is a chapter from the article, “From Conflict to Communion: Going Home to Rome,” which addresses various issues in the LWF/Vatican report From Conflict to Communion (C2C). C2C purports to be a candid look at where things stand between Lutherans and Roman Catholics. In fact C2C has an agenda: It directs Lutherans to be PC so that in time they can be RC. The full article includes the following chapters: 1. Lutherans and Catholics agree/disagree on baptism. 2. C2C declares JDDJ has the “highest level of authority.” (¶97) 3. Justification must decrease so that unity may increase. 4. C2C conceals the Catholic rejection of “faith alone.” 5. C2C’s focus on “Luther’s theology” disguises a caricature of Luther. 6. Why not rescind the 1521 excommunication of Luther? 7. C2C creates a caricature of Luther on scripture by omitting its gospel center. 8. C2C hides the Vatican view: Lutherans are not really, truly “Church.” 9. C2C assumes papal primacy and infallibility are inevitable. 10. Mary, Mary, why are they hiding you? 11. C2C glides over the ordination of women. 12. C2C kicks the can down the road: Lutherans must concede to unity on Rome’s terms. * * * * * 6. Why not rescind the 1521 excommunication of Luther? On June 15, 1520, Pope Leo X issued his bull, Exsurge Domine (“Arise, O Lord, and judge your cause….The wild boar from the forest seeks to destroy [the vineyard]”), threatening Luther, “the wild boar,” with excommunication. -

Confessio Im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- Und Fremdwahrnehmung in Der Frühen Neuzeit

Mona Garloff / Christian Volkmar Witt (Hg.) Confessio im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- und Fremdwahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit. Ein Studienbuch © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Abteilung für Abendländische Religionsgeschichte Herausgegeben von Irene Dingel Beiheft 129 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Confessio im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- und Fremdwahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit Ein Studienbuch Herausgegeben von Mona Garloff und Christian Volkmar Witt Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Die Publikation wurde gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über https://dnb.de abrufbar. © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen Dieses Material steht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 International. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz zu sehen, besuchen Sie http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/4.0/. Satz: Vanessa Weber, Mainz Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2197-1056 ISBN (Print) 978-3-525-57142-2 ISBN (OA) 978-3-666-57142-8 https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Inhalt Vorwort .............................................................................................................. 7 Christian V. Witt Wahrnehmung, Konflikt und Confessio. Eine Einleitung ........................ -

Die Bibelübersetzung Martin Luthers

TY3003 – Sprachwissenschaftlicher D-Aufsatz Björn Kinding – Högskolan Dalarna VT11 TY3003 – Sprachwissenschaftlicher D-Aufsatz Björn Kinding – Högskolan Dalarna VT11 DIE BIBELÜBERSETZUNG MARTIN LUTHERS: EINE SOZIOLINGUISTISCHE ANALYSE DER ABSICHT, DER METHODE UND DER AUSWIRKUNG - 1/87 - TY3003 – Sprachwissenschaftlicher D-Aufsatz Björn Kinding – Högskolan Dalarna VT11 Abstrakt Brundin (2004, S. 63) sagt, dass sich die Reformation „um einen Kampf handelte, der Auswirkungen auf die ganze gesellschaftliche Struktur hatte.“ Das Ziel dieser Arbeit ist die Absichten hinter, die linguistischen Methoden und die sozialen Auswirkungen der Bibelübersetzung Luthers festzustellen, und dadurch die Aussage Brundins zu bestätigen bzw. widerlegen. Es wurde gefunden, dass Martin Luther die Bibelübersetzung und die Reformation in enger Zusammenarbeit mit seinen Kollegen an der Leucorea Universität und unter Führung des sächsischen Kurfürsten, Friedrich III., durchgeführt hat. Dabei haben die verwendeten linguistischen Methoden eine Schlüsselrolle gespielt, und viele heute bekannten wissenschaftlichen Theorien sind praktisch umgesetzt worden. Dazu gehören die Sapir-Whorf-Hypothese, die Defizit- bzw. die Differenzhypothese und die Diskurstheorie. Die Reformation hat eine gewaltige Machtverschiebung zur Folge, wo der Klerus dem Adel viele Rechte abgeben müsste, und die neu erzeugte Sprache der Lutherbibel hat zu einer deutschen Einheitssprache und die Erstehung eines deutschen Nationalstaates geführt. Als Schlussergebnis kann die Aussage Brundins klar bestätigt -

Martin Luther Extended Timeline Session 1

TIMELINES: MARTIN LUTHER & CHRISTIAN HISTORY A. LUTHER the MAN (1483 – 1546) 1502: Receives B.A. at University of Erfurt 1505: Earns M.A. at Erfurt; begins to study law 1505 Luther “struck by lightning” and vows to become a monk 1505 Luther enters the Order of Augustinian Hermits 1507: Luther is ordained and celebrates his first Mass; he panics during the ceremony 1510: Luther visits Rome as representative of Augustinians 1511: Luther transfers to Wittenberg to teach at the new university. 1512: Luther earns his doctorate of theology 1513: Luther begins lecturing on The Psalms 1515: Luther lectures on Paul’s Epistles to the Romans 1517: October 31, he posts his “95 Theses (points to debate)” concerning indulgences on Wittenberg Church door. 1518: At meeting in Augsburg, Luther defends his theology & refuses to recant 1518: Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony places Luther under his protection. 1519: In debates with Professor John Eck at Leipzig, Luther denies supreme authority of popes and councils 1520: Papal bull (Exsurge Domine) gives Luther 60 days to recant or be excommunicated 1520: Luther burns the papal bull and writes 3 seminal documents: “To the Christian Nobility,” “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church,” & “The Freedom of a Christian” 1521: Luther is excommunicated by the papal bull Decet Romanum Pontificem 1521: He refuses to recant his writings at the Diet of Worms 1521: New HRE Charles V condemns Luther as heretic and outlaw Luther is “kidnapped” and hidden in Wartburg Castle Luther begins translating the New Testament -

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe Is Born in Yorkshire

Chronology of the Reformation 1320: John Wycliffe is born in Yorkshire, England 1369?: Jan Hus, born in Husinec, Bohemia, early reformer and founder of Moravian Church 1384: John Wycliffe died in his parish, he and his followers made the first full English translation of the Bible 6 July 1415: Jan Hus arrested, imprisoned, tried and burned at the stake while attending the Council of Constance, followed one year later by his disciple Jerome. Both sang hymns as they died 11 November 1418: Martin V elected pope and Great Western Schism is ended 1444: Johannes Reuchlin is born, becomes the father of the study of Hebrew and Greek in Germany 21 September 1452: Girolamo Savonarola is born in Ferrara, Italy, is a Dominican friar at age 22 29 May 1453 Constantine is captured by Ottoman Turks, the end of the Byzantine Empire 1454?: Gütenberg Bible printed in Mainz, Germany by Johann Gütenberg 1463: Elector Fredrick III (the Wise) of Saxony is born (died in 1525) 1465 : Johannes Tetzel is born in Pirna, Saxony 1472: Lucas Cranach the Elder born in Kronach, later becomes court painter to Frederick the Wise 1480: Andreas Bodenstein (Karlstadt) is born, later to become a teacher at the University of Wittenberg where he became associated with Luther. Strong in his zeal, weak in judgment, he represented all the worst of the outer fringes of the Reformation 10 November 1483: Martin Luther born in Eisleben 11 November 1483: Luther baptized at St. Peter and St. Paul Church, Eisleben (St. Martin’s Day) 1 January 1484: Ulrich Zwingli the first great Swiss -

Die Einladung Martin Luthers Nach Salzburg Im Herbst 1518 127-159 © Gesellschaft Für Salzburger Landeskunde, Salzburg, Austria; Download Unter 127

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Mitt(h)eilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 151 Autor(en)/Author(s): Sallaberger Johann Artikel/Article: Die Einladung Martin Luthers nach Salzburg im Herbst 1518 127-159 © Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, Salzburg, Austria; download unter www.zobodat.at 127 Die Einladung Martin Luthers nach Salzburg im Herbst 1518 Von Johann Sallaberger Im Jahre 1556 erschien in Jena der erste Band einer Sammlung von Luther- Briefen, die der evangelische Theologe Johannes Aurifaber herausgab. Dieser war aus Sachsen gebürtig, hatte Luther gegen Ende seines Lebens als Famulus gedient und war auch bei dessen Tod in Eisleben am 18. Februar 1546 zugegen gewesen. Er galt als eifriger Sammler von Luther betreffenden Schriftstücken1. In diesem Band gedruckter Luther-Briefe findet sich auch ein nicht mehr im Original er haltenes Schreiben, das der damalige Vorgesetzte Luthers, Johann von Staupitz, am Fest „Kreuzerhöhung“ (14. September) des Jahres 1518 aus Salzburg an den Reformator richtete, in dem er Luther einlud, zu ihm zu kommen, um „mit ihm zusammen zu leben und zu sterben“ (ut simul vivamus moriamurque). Diese Ein ladung an Luther, nach Salzburg zu kommen, ausgesprochen noch während der Regierungszeit des bekannten Salzburger Erzbischofs Leonhard von Keutschach, dessen eindrucksvolles Denkmal und dessen sehenswerte Fürstenzimmer auf der Festung Hohensalzburg wohl allgemein bekannt sind, hat in der kirchlichen und profanen Geschichtsschreibung Salzburgs bisher wenig Beachtung gefunden2. Die folgende Studie möchte daher auf dieses interessante Schriftstück hinweisen und zugleich den Versuch unternehmen, die Hintergründe dieses Schreibens zu be leuchten. -

A Man Named Martin Part 1: the Man Session Three

A Man Named Martin Part 1: The Man Session Three Pope Leo X Pope Leo X: This article gives a biography of Pope Leo X, all that he was involved in, and why he needed so much money. The Medici Family: This article traces the history and powerful influence of the Medici family, of which Pope Leo X was a member. St. Peter's Basilica: This article gives the history of the basilica, from Peter’s martyrdom to its construction in Luther’s time. The Roman Catholic Church in the Late Middle Ages: This article describes the structure of the Roman Catholic Church, the various offices, and monastic movements. Indulgences Roman Teachings about Indulgences: DELTO (Distance Education Leading to Ordination) video with Dr. Paul Robinson (Church History 2, Volume 3). When did Indulgences Begin? DELTO (Distance Education Leading to Ordination) video with Dr. Paul Robinson (Church History 2, Volume 4). John Tetzel: This brief biography describes the Dominican monk who stirred Luther’s response to indulgences. How did Luther Come to Preach Against Indulgences?: DELTO (Distance Education Leading to Ordination) video with Dr. Paul Robinson (Church History 2, Volume 8). Image of an Indulgence: This is a link to an image of an indulgence. It is written in German, but you’ll recognize the signature of Johannes Tetzel. Frederick the Wise Heroes and Saints of the Reformation: Frederick the Wise (1463-1525): This article introduces us to Frederick the Wise. 1 Religious Relics Frederick the Wise boasted a collection of thousands of relics. Here are some links that provide more information about them: Top 10 Religious Relics: Time magazine looks at the lore and whereabouts of religious relics from Christianity, Buddhism and Islam. -

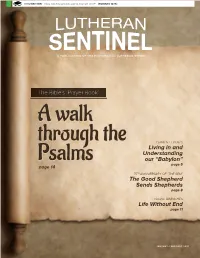

The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds Life Without End the Bible's

IT IS WRITTEN: “How can they preach, unless they are sent?” (ROMANS 10:15) A PUBLICATION OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD The Bible’s ‘Prayer Book’ A walk through the CURRENT EVENTS Living in and Understanding our “Babylon” Psalms page 5 page 14 75TH ANNIVERSARY OF “THE SEM” The Good Shepherd Sends Shepherds page 8 YOUNG BRANCHES Life Without End page 11 JANUARY– FEBRUARY 2021 FROM THE PRESIDENT: by REV. JOHN A. MOLDSTAD, President EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN SYNOD, Mankato, Minn. HowVaporVapor Makes Plans Dear Members and Friends of our ELS: We know what happens when a glass of hot water is placed his ventures, and now he was doing even more expansion. outside on an icy morning. For a time, vapor rises when the When I interjected, “I guess the Lord has really blessed you,” heat meets the cold. Then it quickly disappears. That rising I could sense he felt momentarily uneasy. He did not speak vapor is used by the writer of James to have us reflect on at all of his accomplishments as gifts from God. He replied, the way we go about our lives in making plans. Planning for “Well, I don’t mean to be ‘brag-tocious’ but…” Then he quickly the new year – a year we pray will not repeat the pandemic launched into more of his lucrative plans. challenges of 2020 – needs always to consider what James wrote by inspiration of God the Holy Spirit: Now listen, you Could we also be guilty of the sin of boasting in a less obvious who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go to this or that city, way? Our sinful mind that we carry with us daily as unwanted spend a year there, carry on business and make money.” baggage tempts us to leave God out of the picture. -

Martín Lutero 1 Martín Lutero

Martín Lutero 1 Martín Lutero Martín Lutero Lutero a los 46 años de edad (Lucas Cranach el Viejo, 1529) Nacimiento 10 de noviembre de 1483 Eisleben, Electorado de Sajonia, Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico Fallecimiento 18 de febrero de 1546 (62 años) Eisleben, Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico Ocupación Teólogo Cónyuge Catalina de Bora Firma Martín Lutero (10 de noviembre de 1483 – 18 de febrero de 1546), nacido en Eisleben, Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico (actual Alemania) como Martin Luder,[1] después cambiado a Martin Luther, como es conocido en alemán, fue un teólogo y fraile católico agustino que comenzó e impulsó la reforma religiosa en Alemania, y en cuyas enseñanzas se inspiró la Reforma Protestante y la doctrina teológica y cultural denominada luteranismo. Lutero se caracterizó por exhortar a que la Iglesia cristiana regresara a las enseñanzas originales de la Biblia, impulsando con ello una restructuración de las iglesias cristianas en Europa. La reacción de la Iglesia Católica Romana ante la reforma protestante, fue la Contrarreforma. Sus contribuciones a la civilización El Sello de Lutero. occidental se llegan a considerar más allá del ámbito religioso, ya que sus traducciones de la Biblia ayudaron a desarrollar una versión estándar de la lengua alemana y se convirtieron en un modelo en el arte de la traducción. Su matrimonio con Catalina de Bora el 13 de junio de 1525 inició un movimiento de apoyo al matrimonio sacerdotal dentro de muchas corrientes cristianas. Martín Lutero 2 Primeros años de vida Hijo de Hans y Margarette Lutero, Martín nació el 10 de noviembre de 1483 en Eisleben (Alemania) y fue bautizado el día que se celebraba la festividad de San Martín de Tours. -

Studia Podlaskie

UNIWERSYTET W BIAŁYMSTOKU INSTYTUT HISTORII I NAUK POLITYCZNYCH STUDIA PODLASKIE TOM XXV Białystok 2017 Rada Naukowa Adam Czesław Dobroński, Edmund Jarmusik (GUP im. Janki Kupały), Eriks¯ J¯ekabsons (UŁ, Ryga), Elżbieta Kaczyńska, Jan Kofman, Rafał Kosiński (UwB), Cezary Kuklo (UwB), Adam Manikowski, Rimantas Miknys (LII, Wilno), Halina Parafianowicz (UwB), Jerzy Urwanowicz (UwB), Barbara Stępniewska-Holzer, Oleksandr Zaytsew (UUK, Lwów) Redakcja Elżbieta Bagińska (sekretarz naukowy), Józef Maroszek (redaktor naczelny), Joanna Sadowska, Jan Snopko (zastępca redaktora), Wojciech Śleszyński (zastępca redaktora), Jan Tęgowski Recenzenci Radosław Bania (UŁ), Kazimierz Bem (First Church in Marlborough (Congregational) UCC), Adam Czesław Dobroński, Marcin Hintz (ChAT), Janusz Hochleitner (UWM), Urszula Kuszyńska (Skansen Kurpiowski w Nowogrodzie), Jarosław Ławski (UwB), Karol Łopatecki (UwB), Jan Jerzy Milewski, Paweł Siwiec (UJ), Grzegorz Skommer (UAM) Adres Redakcji Instytut Historii i Nauk Politycznych, Uniwersytet w Białymstoku pl. NZS 1, 15-420 Białystok, tel. +48 85 745 74 44, tel./fax +48 85 745 74 43 e-mail: [email protected], http://www.studiapodlaskie.pl ISSN 0867–1370 DOI: 10.15290/sp.2017.25 c Copyright by Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, Białystok 2017 Redakcja i korekta wersji polskiej: Janina Demianowicz Redakcja techniczna i skład: Stanisław Żukowski Opracowanie streszczeń i tłumaczenie spisu treści w języku angielskim: Ewa Wyszczelska Native speaker: Kirk Palmer Indeksacja: BazHum, CEJSH, Index Copernicus Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku 15-097 Białystok, ul. Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie 14, tel. 85 745 71 20 http://wydawnictwo.uwb.edu.pl, e-mail: [email protected] Druk i oprawa: Volumina.pl. Daniel Krzanowski SPIS TREŚCI I. ARTYKUŁY Margriet Gosker – Luther’s Legacy after 500 Years. Some thoughts from a Dutch point of view ..................................... -

History of the Lutheran Reformation

Celebrating the 500 th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation Sola Gratia Grace Alone Sola Fide Faith Alone Sola Scriptura Scripture Alone Martin Luther nailing his 95 Theses on the church door. Wittenberg, Germany. October 31, 1517 Contents Main People.............................................................................................1 Important Words......................................................................................2 Important Cities.......................................................................................4 Reformation Map ....................................................................................5 Chronology..............................................................................................6 Contents of the Book of Concord............................................................8 Luther's 95 Theses...................................................................................9 Luther's own description of the Reformation........................................14 Who Are Lutherans? .............................................................................19 The Lutheran Reformation Main People Earlier Reformers John Wycliffe (died 1384) -- England, translated the Latin Bible to English Jan (John) Hus (died 1415) -- Bohemia, executed (burned at the stake) People with Luther Johann Staupitz -- Luther's mentor, head of the Augustinian monastery Duke Frederick the Wise of Saxony -- Luther's protector Georg Spalatin -- Duke Frederick's assistant and problem solver in -

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION at 500 YEARS from RUPTURE to DIALOGUE Jaume Botey

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION AT 500 YEARS FROM RUPTURE TO DIALOGUE Jaume Botey 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 2. Luther’s personality and the theme of justification ...................... 7 3. The great controversies, and the progressive development of his thought ................................................................. 10 4. The great treatises of 1520 and the diet of worms .......................... 16 5. The peasants’ war .................................................................................... 21 6. Consolidation of the reformation ....................................................... 24 7. Epilogue .................................................................................................... 28 Notes ............................................................................................................. 31 Bibliography ................................................................................................. 32 In memory… In February, while we were preparing the English edition of this booklet, its author, Jaume Botey Vallés, passed away. As a member of the Cristianisme i Justícia team, Jaume was a person profoundly committed to ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, and he worked energetically for peace and for the other world that is possible. Jaume, we will miss you greatly. Cristianisme i Justícia Jaume Botey has a licentiate in philosophy and theology and a doctorate in anthropology. He has been a professor of