Attica in Syria»

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

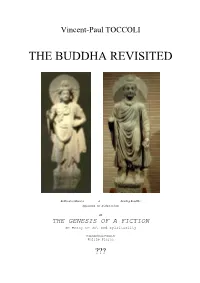

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Ovid Book 12.30110457.Pdf

METAMORPHOSES GLOSSARY AND INDEX The index that appeared in the print version of this title was intentionally removed from the eBook. Please use the search function on your eReading device to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that ap- pear in the print index are listed below. SINCE THIS index is not intended as a complete mythological dictionary, the explanations given here include only important information not readily available in the text itself. Names in parentheses are alternative Latin names, unless they are preceded by the abbreviation Gr.; Gr. indi- cates the name of the corresponding Greek divinity. The index includes cross-references for all alternative names. ACHAMENIDES. Former follower of Ulysses, rescued by Aeneas ACHELOUS. River god; rival of Hercules for the hand of Deianira ACHILLES. Greek hero of the Trojan War ACIS. Rival of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, for the hand of Galatea ACMON. Follower of Diomedes ACOETES. A faithful devotee of Bacchus ACTAEON ADONIS. Son of Myrrha, by her father Cinyras; loved by Venus AEACUS. King of Aegina; after death he became one of the three judges of the dead in the lower world AEGEUS. King of Athens; father of Theseus AENEAS. Trojan warrior; son of Anchises and Venus; sea-faring survivor of the Trojan War, he eventually landed in Latium, helped found Rome AESACUS. Son of Priam and a nymph AESCULAPIUS (Gr. Asclepius). God of medicine and healing; son of Apollo AESON. Father of Jason; made young again by Medea AGAMEMNON. King of Mycenae; commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Trojan War AGLAUROS AJAX. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10444-0 — Rome and the Third Macedonian War Paul J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10444-0 — Rome and the Third Macedonian War Paul J. Burton Index More Information Index Abdera, Greek city on the h racian coast, 15n. second year 41 , 60 , 174 political disruption sparked by Roman h ird Macedonian War embassy, 143 second year troubles with Sparta, 13 , 82n. 23 brutalized by Hortensius, 140 Acilius Glabrio, M’. (cos. 191), 44 , 59n. 12 embassy to Rome, 140 Aetolian War s.c. de Abderitis issued, 140 , see also second year Appendix C passim given (unsolicited) strategic advice by Abrupolis, king of the h racian Sapaei, 15n. 41 Flamininus, 42 attacks Macedonia (179), 58 , 81 Syrian and Aetolian Wars Acarnania, Acarnanians, 14 second year deprived of the city of Leucas (167), 177 Battle of h ermopylae, 36 – 37 First Macedonian War recovers some cities in h essaly, 36 Roman operations in (211), 25 Aelius Ligus, P. (cos. 172), 112 politicians exiled to Italy (167), 177 Aemilius Lepidus, M. (ambassador) h ird Macedonian War embassy to Philip V at Abydus (200), 28 , second year 28n. 53 political disruption sparked by Roman Aenus and Maronea, Greek cities on the embassy, 143 h racian coast, 40 , 60 , 140 , 174 two executed by the Athenians (201), 28n. 53 declared free by the senate, 46 – 47 Achaean League, Achaeans, 12 – 13 dispute between Philip V and Rome over, Achaean War (146), 194 44 – 45 , 55 , 86 , 92 , 180 Archon- Callicrates debate (175), 61 , 61n. 29 , embassy to Rome from Maronean exiles (186/ 62n. 30 , 94 – 96 5), 45 congratulated by Rome for resisting Perseus Maronean exiles address senatorial (173), 66 , 117 commission (185), 46 conquest of the Peloponnese, 13 , 82n. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

A Glimpse Into the Roman Finances of the Second Punic War Through

Letter Geochemical Perspectives Letters the history of the western world. Carthage was a colony founded next to modern Tunis in the 8th century BC by Phoenician merchants. During the 3rd century BC its empire expanded westward into southern Spain and Sardinia, two major silver producers of the West Mediterranean. Meanwhile, Rome’s grip had tight- © 2016 European Association of Geochemistry ened over the central and southern Italian peninsula. The Punic Wars marked the beginning of Rome’s imperial expansion and ended the time of Carthage. A glimpse into the Roman finances The First Punic War (264 BC–241 BC), conducted by a network of alliances in Sicily, ended up with Rome prevailing over Carthage. A consequence of this of the Second Punic War conflict was the Mercenary War (240 BC–237 BC) between Carthage and its through silver isotopes unpaid mercenaries, which Rome helped to quell, again at great cost to Carthage. Hostilities between the two cities resumed in 219 BC when Hannibal seized the F. Albarède1,2*, J. Blichert-Toft1,2, M. Rivoal1, P. Telouk1 Spanish city of Saguntum, a Roman ally. At the outbreak of the Second Punic War, Hannibal crossed the Alps into the Po plain and inflicted devastating mili- tary defeats on the Roman legions in a quick sequence of major battles, the Trebia (December 218 BC), Lake Trasimene (June 217 BC), and Cannae (August 216 BC). As a measure of the extent of the disaster, it was claimed that more than 100,000 Abstract doi: 10.7185/geochemlet.1613 Roman soldiers and Italian allies lost their lives in these three battles, including The defeat of Hannibal’s armies at the culmination of the Second Punic War (218 BC–201 three consuls. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

THE CHURCHES of GALATIA. PROFESSOR WM RAMSAY's Very

THE CHURCHES OF GALATIA. NOTES ON A REGENT CONTROVERSY. PROFESSOR W. M. RAMSAY'S very interesting and impor tant work on The Church in the Roman Empire has thrown much new light upon the record of St. Paul's missionary journeys in Asia Minor, and has revived a question which of late years had seemingly been set at rest for English students by the late Bishop Lightfoot's Essay on "The Churches of Galatia" in the Introduction to his Commen tary on the Epistle to the Galatians. The question, as there stated (p. 17), is whether the Churches mentioned in Galatians i. 2 are to be placed in "the comparatively small district occupied by the Gauls, Galatia properly so called, or the much larger territory in cluded in the Roman province of that name." Dr. Lightfoot, with admirable fairness, first points out in a very striking passage some of the " considerations in favour of the Roman province." " The term 'Galatia,' " he says, " in that case will comprise not only the towns of Derbe and Lystra, but also, it would seem, !conium and the Pisidian Antioch; and we shall then have in the narrative of St. Luke (Acts xiii. 14-xiv. 24) a full and detailed account of the founding of the Galatian Churches." " It must be confessed, too, that this view has much to recom mend it at first sight. The Apostle's account of his hearty and enthusiastic welcome by the Galatians as an angel of God (iv. 14), would have its counterpart in the impulsive warmth of the barbarians at Lystra, who would have sacri ficed to him, imagining that 'the gods had come down in VOL. -

Antiochus IV Rome

Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 11 & 12 Babylon Medo- 445BC 4 Persian Kings Persia Alex the Great Greece N&S Kings Antiochus IV Rome Gap of Time Time of the Gentiles 1wk 3 ½ years Opposing king. Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes Daniel 9:27 The 70th Week 1 Week = 7 years 3 ½ years 3 ½ years Apostasy Make a covenant Stop to Temple sacrifice with the many Stop to grain offering Abomination of Desolation Crush the elect (Jews) Jacob’s Distress Jacob’s Trouble Tribulation Daniel 11:35 Some of those who have insight will fall, in order to refine, purge and make them pure until the end time; because it is still to come at the appointed time 1 John 3:2-3 2 Beloved, now we are children of God, and it has not appeared as yet what we will be. We know that when He appears, we will be like Him, because we will see Him just as He is. 3 And everyone who has his hope fixed on Him purifies himself, just as He is pure. Zechariah 13:7-9 8 “It will come about in all the land,” Declares the LORD, “That two parts in it will be cut off and perish; But the third will be left in it. -

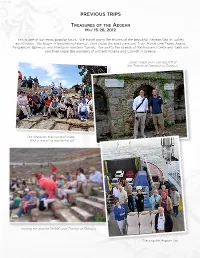

Previous Trips

PREVIOUS TRIPS TREASURES OF THE AEGEAN MAY 15-26, 2012 This is one of our most popular tours. We travel along the shores of the beautiful Aegean Sea in Turkey and Greece. We begin in fascinating Istanbul, then cross the sea to ancient Troy, Alexandria Troas, Assos, Pergamum, Ephesus, and Miletus in western Turkey. We sail to the islands of Patmos and Crete and Santorini and then share the wonders of ancient Athens and Corinth in Greece. Jacob Shock and Evan Bassett at the Temple of Domitian in Ephesus Our Group on the island of Crete – With a few of us wandering off Visiting the ancient 24,000 seat Theater at Ephesus Crossing the Aegean Sea PREVIOUS TRIPS TREASURES OF THE AEGEAN MAY 15-26, 2012 This is one of our most popular tours. We travel along the shores of the beautiful Aegean Sea in Turkey and Greece. We begin in fascinating Istanbul, then cross the sea to ancient Troy, Alexandria Troas, Assos, Pergamum, Ephesus, and Miletus in western Turkey. We sail to the islands of Patmos and Crete and Santorini and then share the wonders of ancient Athens and Corinth in Greece. Don and grandson Evan at Assos Mars Hill in Athens Well known archaeologist, Cingiz Icten, is pictured with Jacob Shock (left), guide Yeldiz Ergor, and Nancy and Don Bassett at the recently excavated Slope Houses in Ephesus Nancy and her brother Jack Woolf in Istanbul PREVIOUS TRIPS IN THE STEPS OF MOSES AND JOSHUA EGYPT, SINAI, JORDAN, ISRAEL MAY 5-20, 2010 This great tour began with visits to the Giza Pyramids, the Cairo Museum, and the amazing new Library of Alexandria.