Silence Or Death in Mexico's Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Invisibile 2014-The Killing-Flyer

cinema LUX cinema invisibile febbraio > maggio 2014 martedì ore 21.00 giovedì ore 18.30 The Killing - Linden, Holder e il caso Larsen The Killing serie tv - USA stagione 1 (2011) + stagione 2 (2012) 13 episodi + 13 episodi Seattle. Una giovane ragazza, Rosie Larsen, viene uccisa. La detective Sarah Linden, nel suo ultimo giorno di lavoro alla omicidi, si ritrova per le mani un caso complicato che non si sente di lasciare al nuovo collega Stephen Holder, incaricato di sostituirla. Nei 26 giorni delle indagini (e nei 26 episodi dell'avvincente serie tv) la città mostra insospettate zone d'ombra: truci rivelazioni e insinuanti sospetti rimbalzano su tutto il contesto cittadino, lacerano la famiglia Larsen (memorabile lo struggimento progressivo di padre, madre e zia) e sconvolgono l'intera comunità non trascurando politici, insegnanti, imprenditori, responsabili di polizia... The Killing vive di atmosfere tese e incombenti e di un ritmo pacato, dal passo implacabile e animato dai continui contraccolpi dell'investigazione, dall'affollarsi di protagonisti saturi di ambiguità con responsabilità sempre più difficili da dissipare. Seattle, con il suo grigiore morale e la sua fitta trama di pioggia, accompagna un'indagine di sofferto coinvolgimento emotivo per il pubblico e per i due detective: lei taciturna e introversa, “incapsulata” nei suoi sgraziati maglioni di lana grossa; lui, dal fascino tenebroso, con un passato di marginalità sociale e un presente tutt’altro che rassicurante. Il tempo dell'indagine lento e prolungato di The Killing sa avvincere e crescere in partecipazione ed angoscia. Linden e Holder (sempre i cognomi nella narrazione!) faticheranno a dipanare il caso e i propri rapporti interpersonali, ma l'alchimia tra una regia impeccabile e un calibrato intreccio sa tenere sempre alta la tensione; fino alla sconvolgente soluzione del giallo, in cui alla beffa del destino, che esalta il cinismo dei singoli e scardina ogni acquiescenza familiare, può far da contraltare solo la toccante compassione per la tragica fine di Rosie. -

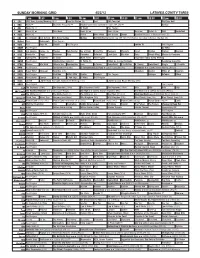

Sunday Morning Grid 3/25/12

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/25/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning Å Face/Nation Doodlebops Doodlebops College Basket. 2012 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Wall Street Golf Digest Special Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) IndyCar Racing Honda Grand Prix of St. Petersburg. (N) XTERRA World Champ. 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Doubt ››› (2008) 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Quest Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth Death, sacrifice and rebirth. Å 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Noticias Univision Santa Misa Desde Guanajuato, México. República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Misión S.O.S. Toonturama Presenta Karate Kid ›› (1984, Drama) Ralph Macchio. -

Justice-Reform

Mexico Institute SHARED RESPONSIBILITY: U.S.-MEXICO POLICY OPTIONS FOR CONFRONTING ORGANIZED CRIME Edited by Eric L. Olson, David A. Shirk, and Andrew Selee Mexico Institute Available from: Mexico Institute Trans-Border Institute Woodrow Wilson International University of San Diego Center for Scholars 5998 Alcalá Park, IPJ 255 One Woodrow Wilson Plaza San Diego, CA 92110-2492 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.sandiego.edu/tbi www.wilsoncenter.org/mexico ISBN : 1-933549-61-0 October 2010 The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan institution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television, and the monthly news-letter “Centerpoint.” For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. -

![Revista De Estudios Sociales, 73 | 01 Julio 2020, «Violencia En América Latina Hoy» [En Línea], Publicado El 19 Junio 2020, Consultado El 04 Mayo 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4029/revista-de-estudios-sociales-73-01-julio-2020-%C2%ABviolencia-en-am%C3%A9rica-latina-hoy%C2%BB-en-l%C3%ADnea-publicado-el-19-junio-2020-consultado-el-04-mayo-2021-404029.webp)

Revista De Estudios Sociales, 73 | 01 Julio 2020, «Violencia En América Latina Hoy» [En Línea], Publicado El 19 Junio 2020, Consultado El 04 Mayo 2021

Revista de Estudios Sociales 73 | 01 julio 2020 Violencia en América Latina hoy Edición electrónica URL: https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/47847 ISSN: 1900-5180 Editor Universidad de los Andes Edición impresa Fecha de publicación: 1 julio 2020 ISSN: 0123-885X Referencia electrónica Revista de Estudios Sociales, 73 | 01 julio 2020, «Violencia en América Latina hoy» [En línea], Publicado el 19 junio 2020, consultado el 04 mayo 2021. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/ 47847 Este documento fue generado automáticamente el 4 mayo 2021. Los contenidos de la Revista de Estudios Sociales están editados bajo la licencia Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 1 ÍNDICE Dossier Violencia en América Latina hoy: manifestaciones e impactos Angelika Rettberg Untangling Violent Legacies: Contemporary Organized Violence in Latin America and the Narrative of the “Failed Transition” Victoria M. S. Santos Glass Half Full? The Peril and Potential of Highly Organized Violence Adrian Bergmann Jóvenes mexicanos: violencias estructurales y criminalización Maritza Urteaga Castro-Pozo y Hugo César Moreno Hernández Letalidade policial e respaldo institucional: perfil e processamento dos casos de “resistência seguida de morte” na cidade de São Paulo Rafael Godoi, Carolina Christoph Grillo, Juliana Tonche, Fábio Mallart, Bruna Ramachiotti y Paula Pagliari de Braud “Si realmente ustedes quieren pegarle, no nos llamen, llámenos después que le pegaron y váyanse”. Justicia por mano propia en Ciudad de México Elisa Godínez Pérez El cuerpo de los condenados. Cárcel y violencia en América Latina Libardo José Ariza y Fernando León Tamayo Arboleda La política de seguridad en El Salvador: la construcción del enemigo y sus efectos en la violencia y el orden social Viviana García Pinzón y Erika J. -

No Veo, No Hablo Y No Escucho : Retrato Del Periodismo Veracruzano

Universidad de San Andrés Departamento de Ciencias Sociales Maestría en Periodismo No veo, no hablo y no escucho : retrato del periodismo veracruzano Autor: Alfaro Vega, Dora Iveth Legajo: 0G05763726 Director de Tesis: Vargas, Inti | Castells i Talens, Antoni México, 2 de marzo de 2018 1 Universidad de San Andrés y Grupo Clarín Maestría en Periodismo. Dora Iveth Alfaro Vega. “No veo, no hablo y no escucho: retrato del periodismo veracruzano”. Tutores: Inti Vargas y Antoni Castells i Talens. México a 2 de marzo de 2018. 2 PARTE 1: INVESTIGACIÓN PERIODÍSTICA ______________________________ 3 Justificación: el trayecto _________________________________________________________________ 3 El adiós. No veo, no hablo y no escucho _____________________________________________________ 8 Unas horas antes ______________________________________________________________________ 16 ¿Por qué? ____________________________________________________________________________ 30 México herido _______________________________________________________________________ 30 Tierra de periodistas muertos ___________________________________________________________ 31 Los primeros atentados ________________________________________________________________ 32 Prueba y error: adaptándose a la violencia _________________________________________________ 35 Nóminas y ‘paseos’ __________________________________________________________________ 37 Los mensajes________________________________________________________________________ 43 Milo Vela y su familia ________________________________________________________________ -

Tesis Doctoral Marti

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA COMUNICACIÓN Departamento de Ciencias de la Comunicación y Sociología UNA PROFESIÓN DE RIESGO La seguridad de los periodistas en sociedades con problemas de violencia Tesis Doctoral Presentada por: Martín Antonio Zermeño Muñoz Director: Dr. Manuel Martínez Nicolás Madrid, 2015 INFORME DEL DIRECTOR DE LA TESIS DOCTORAL Manuel Martínez Nicolás , con DNI 21.449.561 Z, director de la Tesis Doctoral Una profesión de riesgo. La seguridad de los periodistas en sociedades con problemas de violencia , de la que es autor D. MARTÍN ANTONIO ZERMEÑO MUÑOZ , certifica que el trabajo cumple con los criterios y requisitos científicos exigibles para su presentación y defensa ante un tribunal académico. En Fuenlabrada (Madrid), a 30 de octubre de 2015 Manuel Martínez Nicolás Director de la Tesis Doctoral A mi Familia Margarita, mi Madre; Carmen, mi Esposa; y mis Hijos Alejandra, Martín y Fernanda A mis compañeros Del Foro de Periodistas de Chihuahua Del Colegio de Periodistas “José Vasconcelos AGRADECIMIENTOS Siempre agradeceré la oportunidad de las autoridades y profesores de la Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, mi Alma Máter que me apoyaron y animaron para iniciar y llegar a la difícil meta de concluir este trabajo doctoral en una institución educativa española de la relevancia de la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Al hacer un alto en el camino para reflexionar sobre los poco más de 30 años que he trabajado en el periodismo y en torno al ejercicio académico, nuevamente solo queda agradecer a quienes me dieron la oportunidad de iniciarme en este apasionante oficio, hoy convertido en una de la profesiones de mayor influencia, responsabilidad y, por lo mismo, peligrosa en el mundo. -

United States District Court Eastern District of New York

Case 1:17-cv-06645-NGG-CLP Document 1 Filed 11/14/17 Page 1 of 111 PageID #: 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK Mary M. Zapata (Individually and as ) Administrator of the Estate of Jaime J. ) Zapata); Amador Zapata, Jr.; Amador Zapata ) III (Individually and as Administrator of the ) Estate of Jaime J. Zapata); Carlos Zapata; Jose ) Zapata; E. William Zapata; Victor Avila, Jr. ) (Individually and as Guardian for S.A. and ) V.E.A.); Claudia Avila (Individually and as ) Case Action No. ____________ Guardian for S.A. and V.E.A.); Victor Avila; ) Magdalena Avila; Magdalena Avila ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Villalobos; Jannette Quintana; Mathilde ) Cason (Individually and as Administrator of ) the Estate of Arthur and Lesley Redelfs, and ) as Guardian for R.R.); Robert Cason; ) Reuben Redelfs; Paul Redelfs; Katrina ) Redelfs Johnson; Beatrice Redelfs Duran; ) Rafael Morales (Individually and as ) Administrator of the Estate of Rafael ) Morales Valencia); Maria Morales; Moraima ) PLAINTIFFS’ COMPLAINT Morales Cruz (Individually and as Guardian ) for G.C., A.C., and N.C.); Juan Cruz; ) Lourdes Batista (Individually and as ) Administrator of the Estate of Felix Batista), ) Adrielle Batista, Amari Batista, Alysandra ) Batista, Andrea Batista, Adam Batista, ) Marlene Norono, and Jacqueline Batista, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) HSBC Holdings plc; HSBC Bank U.S.A., ) N.A.; HSBC México S.A., Institución de ) Banca Múltiple, Grupo Financiero HSBC; ) and Grupo Financiero HSBC, S.A. de C.V., ) ) Defendants. ) Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jurisdiction and Venue ......................................................................................................... 6 Case 1:17-cv-06645-NGG-CLP Document 1 Filed 11/14/17 Page 2 of 111 PageID #: 2 III. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

“ANOTHER KIND OF KNIGHTHOOD”: THE HONOR OF LETRADOS IN EARLY MODERN SPANISH LITERATURE By MATTHEW PAUL MICHEL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Matthew Paul Michel To my friends, family, and colleagues in the Gator Nation ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “This tale grew in the telling,” Tolkien tells his readers in the foreword of The Fellowship of the Ring (1954). For me, what began as little more than a lexical curiosity—“Why is letrado used inconsistently by scholars confronting early modern Spanish literature?”—grew in scope until it became the present dissertation. I am greatly indebted to my steadfast advisor Shifra Armon for guiding me through the long and winding road of graduate school. I would also like to acknowledge a debt of gratitude to the late Carol Denise Harllee (1959-2012), Assistant Professor of Spanish at James Madison University, whose research on Pedro de Madariaga rescued that worthy author from obscurity and partially inspired my own efforts. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1 GATEWAY TO THE LETRADO SOCIOTYPE IN EARLY MODERN SPANISH LITERATURE ..........................................................................................................................9 -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title On Both Sides of the Atlantic: Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/66v5k0qs Author Perez, Karen Patricia Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE On Both Sides of the Atlantic: Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Karen Patricia Pérez December 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. James A. Parr, Chairperson Dr. David K. Herzberger Dr. Sabine Doran Copyright by Karen Patricia Pérez 2013 The Dissertation of Karen Patricia Pérez is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committer Chair, Distinguished Professor James A. Parr, an exemplary scholar and researcher, a dedicated mentor, and the most caring and humble individual in this profession whom I have ever met; someone who at our very first meeting showed faith in me, gave me a copy of his edition of the Quixote and welcomed me to UC Riverside. Since that day, with the most sincere interest and unmatched devotedness he has shared his knowledge and wisdom and guided me throughout these years. Without his dedication and guidance, this dissertation would not have been possible. For all of what he has done, I cannot thank him enough. Words fall short to express my deepest feelings of gratitude and affection, Dr. -

Variables Que Generan Violencia 52 2.6.1

BENEMÉRITA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE PUEBLA FACULTAD DE DERECHO Y CIENCIAS SOCIALES POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS VIOLENCIAS ILEGALES: PERIODISTAS MUERTOS O DESAPARECIDOS ENTRE 2000 Y 2015 TESIS QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE MAESTRO EN CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS PRESENTA LIC. JUAN FRANCISCO GARCÍA MARAÑÓN DIRECTORA DRA. LIDIA AGUILAR BALDERAS PUEBLA, PUE. MAYO 2015 Dedico esta investigación y agradezco: A mi hijo Pablo, esperanza y motivación de vida. A mi familia por el apoyo y el aguante. A la familia de mi hijo por el cariño incondicional. A don Paquillo y doña Susanita, que andarán por ahí, contemplando actos que sonaban imposibles. A la Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales de la BUAP por la generosidad de alumbrar un nuevo rumbo para reinventarme. Al Doctor Francisco Sánchez y su equipo de trabajo en la Coordinación del Posgrado en Ciencias Políticas, por el rigor científico y el afecto, con lo que aprendo a complementar lo cuantitativo y lo cualitativo. A la Dra. Pilar Calveiro por ayudarme a trazar el camino. A la Dra. Lidia Aguilar Balderas por encauzarme hacia la consecución del objetivo. A mis profesoras y profesores de la Maestría en Ciencias Políticas por llevarme de la mano en la senda actual del estado del arte de la disciplina: la Dra. Pilar, el Dr. Samuel, el Dr. Miguel Ángel, el Dr. Israel, el Dr. César, la Dra. Lidia, el Dr. Paco, el Dr. Diego, el Mtro. Hugo, el Dr. Jorge, el Dr. Octavio; gracias por enseñarme que las cosas-y las personas- en este mundo están profundamente ligadas entre sí. A mis compañeras y compañeros de generación de la Maestría, jóvenes talentosos y brillantes con quienes se conformó un excelente grupo de estudio y trabajo. -

The Effects of Drug-War Related Violence on Mexico's Press And

The Effects of Drug-War Related Violence on Mexico’s Press and Democracy EMILY EDMONDS-POLI INTRODUCTION The Mexican government’s multiyear war against drug trafficking and criminal organizations has had many unintended effects. One of them is that Mexico is the most dangerous country in the Western Hemisphere for journalists. As a percentage of the total drug war-related deaths, the deaths of journalists and media workers make up a very small number, yet their significance is undeniable. Not only do they contribute to the country’s overall insecurity, the deaths also threaten the quality of Mexico’s democracy by curtailing freedom of expression because journalists are truly the “eyes and ears of civil society.” Both freedom of expression and access to alternative sources of information, two functions of an independent press, are essential for democracy because they allow citizens to be introduced to new ideas, engage in debate and discussion, and acquire the information they need to understand the issues and policy alternatives. In other words, freedom of expression and information are essential for civic competence and effective participation.1 Furthermore, an independent press is indispensable for monitoring government activity. Without it, citizens may never learn about their leaders’ accomplishments and transgressions, thus compromising their ability to punish, reward, or otherwise hold politicians accountable for their actions. Violence against journalists compromises Mexicans’ right to free expression, which is guaranteed to all citizens by Articles 6 and 7 of the 1917 Mexican Constitution, and also limits the independence and effectiveness of the national press.2 These developments simultaneously are linked to and exacerbate Mexico’s 1 Robert A. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/22/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/22/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid PGA Tour Golf PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Conference Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. (N) Å Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Baseball Dodgers at Houston Astros. (N) 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: STP 400. From Kansas Speedway in Kansas City, Kan. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program 22 Niños 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tú Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Paid Program Toonturama Presenta El Campamento de Papá › (2007, Comedia) (PG) Blankman ›› (1994) Damon Wayans.