Two Tongues for a Dream: a Hermeneutic Study Marta Bachino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Invisibile 2014-The Killing-Flyer

cinema LUX cinema invisibile febbraio > maggio 2014 martedì ore 21.00 giovedì ore 18.30 The Killing - Linden, Holder e il caso Larsen The Killing serie tv - USA stagione 1 (2011) + stagione 2 (2012) 13 episodi + 13 episodi Seattle. Una giovane ragazza, Rosie Larsen, viene uccisa. La detective Sarah Linden, nel suo ultimo giorno di lavoro alla omicidi, si ritrova per le mani un caso complicato che non si sente di lasciare al nuovo collega Stephen Holder, incaricato di sostituirla. Nei 26 giorni delle indagini (e nei 26 episodi dell'avvincente serie tv) la città mostra insospettate zone d'ombra: truci rivelazioni e insinuanti sospetti rimbalzano su tutto il contesto cittadino, lacerano la famiglia Larsen (memorabile lo struggimento progressivo di padre, madre e zia) e sconvolgono l'intera comunità non trascurando politici, insegnanti, imprenditori, responsabili di polizia... The Killing vive di atmosfere tese e incombenti e di un ritmo pacato, dal passo implacabile e animato dai continui contraccolpi dell'investigazione, dall'affollarsi di protagonisti saturi di ambiguità con responsabilità sempre più difficili da dissipare. Seattle, con il suo grigiore morale e la sua fitta trama di pioggia, accompagna un'indagine di sofferto coinvolgimento emotivo per il pubblico e per i due detective: lei taciturna e introversa, “incapsulata” nei suoi sgraziati maglioni di lana grossa; lui, dal fascino tenebroso, con un passato di marginalità sociale e un presente tutt’altro che rassicurante. Il tempo dell'indagine lento e prolungato di The Killing sa avvincere e crescere in partecipazione ed angoscia. Linden e Holder (sempre i cognomi nella narrazione!) faticheranno a dipanare il caso e i propri rapporti interpersonali, ma l'alchimia tra una regia impeccabile e un calibrato intreccio sa tenere sempre alta la tensione; fino alla sconvolgente soluzione del giallo, in cui alla beffa del destino, che esalta il cinismo dei singoli e scardina ogni acquiescenza familiare, può far da contraltare solo la toccante compassione per la tragica fine di Rosie. -

Interliminal Tongues: Self-Translation in Contemporary Transatlantic

INTERLIMINAL TONGUES: SELF-TRANSLATION IN CONTEMPORARY TRANSATLANTIC BILINGUAL POETRY by MICHAEL BRANDON RIGBY A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Romance Languages and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Michael Brandon Rigby Title: Interliminal Tongues: Self-translation in Contemporary Transatlantic Bilingual Poetry This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Romance Languages by: Cecilia Enjuto Rangel Chairperson Amalia Gladhart Core Member Pedro García-Caro Core Member Monique Balbuena Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Michael Brandon Rigby iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Michael Brandon Rigby Doctor of Philosophy Department of Romance Languages June 2017 Title: Interliminal Tongues: Self-translation in Contemporary Transatlantic Bilingual Poetry In this dissertation, I argue that self-translators embody a borderline sense of hybridity, both linguistically and culturally, and that the act of translation, along with its innate in-betweenness, is the context in which self-translators negotiate their fragmented identities and cultures. I use the poetry of Urayoán Noel, Juan Gelman, and Yolanda Castaño to demonstrate that they each uniquely use the process of self- translation, in conjunction with a bilingual presentation, to articulate their modern, hybrid identities. In addition, I argue that as a result, the act of self-translation establishes an interliminal space of enunciation that not only reflects an intercultural exchange consistent with hybridity, but fosters further cultural and linguistic interaction. -

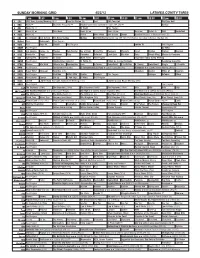

Sunday Morning Grid 3/25/12

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/25/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning Å Face/Nation Doodlebops Doodlebops College Basket. 2012 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Wall Street Golf Digest Special Golf Central PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) IndyCar Racing Honda Grand Prix of St. Petersburg. (N) XTERRA World Champ. 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Doubt ››› (2008) 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Quest Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth Death, sacrifice and rebirth. Å 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Noticias Univision Santa Misa Desde Guanajuato, México. República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Misión S.O.S. Toonturama Presenta Karate Kid ›› (1984, Drama) Ralph Macchio. -

The Guardian, February 04, 2009

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 2-4-2009 The Guardian, February 04, 2009 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (2009). The Guardian, February 04, 2009. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSllY DUNBAR LIBRARY FEB 5 z1 11 i ~. ·wedh ·~~·aay.·'.J 1' • , • ,. •'1 1 Feb. 4; 2009' I· , , - • • • ~ I R GHT S ~TE U E SITY'S CA PU E P PE 3640 Colonel Glenn Hwy. 014 Student Union, Dayton, OH 45435 I Issue No. 15 Vol. 45 A SMA All-American Newspaper Preview to Butler When it comes to Saturday's game, WSU doesn't have just one star pla er--it has three pg a Index Staff List News Editor- in- Chief Chelsey Levingston Events Calendar... 4 [email protected] Business Manager Sponsored by the Women's Alex Hunter Center, featuring student org [email protected] and Women's Center events News Editor Tiffany Johnson [email protected] Assistant News Editor Whitney Wetsig Opinions wetsig .3wright .edu Whitney Wetsig News Writers Editorial .................. 5 [email protected] Ryan Hehr Jan. 27 - A male wa taken int a Tuition freeze harmful for WSU hehr.3 wright .edu Jan. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

“ANOTHER KIND OF KNIGHTHOOD”: THE HONOR OF LETRADOS IN EARLY MODERN SPANISH LITERATURE By MATTHEW PAUL MICHEL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 © 2016 Matthew Paul Michel To my friends, family, and colleagues in the Gator Nation ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “This tale grew in the telling,” Tolkien tells his readers in the foreword of The Fellowship of the Ring (1954). For me, what began as little more than a lexical curiosity—“Why is letrado used inconsistently by scholars confronting early modern Spanish literature?”—grew in scope until it became the present dissertation. I am greatly indebted to my steadfast advisor Shifra Armon for guiding me through the long and winding road of graduate school. I would also like to acknowledge a debt of gratitude to the late Carol Denise Harllee (1959-2012), Assistant Professor of Spanish at James Madison University, whose research on Pedro de Madariaga rescued that worthy author from obscurity and partially inspired my own efforts. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER 1 GATEWAY TO THE LETRADO SOCIOTYPE IN EARLY MODERN SPANISH LITERATURE ..........................................................................................................................9 -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title On Both Sides of the Atlantic: Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/66v5k0qs Author Perez, Karen Patricia Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE On Both Sides of the Atlantic: Re-Visioning Don Juan and Don Quixote in Modern Literature and Film A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Karen Patricia Pérez December 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. James A. Parr, Chairperson Dr. David K. Herzberger Dr. Sabine Doran Copyright by Karen Patricia Pérez 2013 The Dissertation of Karen Patricia Pérez is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committer Chair, Distinguished Professor James A. Parr, an exemplary scholar and researcher, a dedicated mentor, and the most caring and humble individual in this profession whom I have ever met; someone who at our very first meeting showed faith in me, gave me a copy of his edition of the Quixote and welcomed me to UC Riverside. Since that day, with the most sincere interest and unmatched devotedness he has shared his knowledge and wisdom and guided me throughout these years. Without his dedication and guidance, this dissertation would not have been possible. For all of what he has done, I cannot thank him enough. Words fall short to express my deepest feelings of gratitude and affection, Dr. -

Speaking in Two Tongues: an Ethnographic Investigation of the Literacy Practices of English As a Foreign Language and Cambodian Young Adult Learners’ Identity

Speaking in Two Tongues: An Ethnographic Investigation of the Literacy Practices of English as a Foreign Language and Cambodian Young Adult Learners’ Identity Soth Sok Student Number: 3829801 College of Education, Victoria University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education February 2014 Speaking in Two Tongues: An ethnographic investigation of the literacy practices of English as a foreign language and Cambodian young adult learners’ identity Abstract This study focuses on how the literacy practices in English of young Cambodians shaped their individual and social perception as well as performance of identity. It examines the English language as an increasingly dominant cultural and linguistic presence in Cambodia and endeavours to fill the epistemic gap in what Gee (2008, p. 1) has identified as the ‘other stuff’ of language. This other stuff includes ‘social relations, cultural models, power and politics, perspectives on experience, values and attitudes, as well as things and places in the world’ that are introduced to the local culture through English literacy and practices. Merchant and Carrington (2009, p. 63) have suggested that ‘the very process of becoming literate involves taking up new positions and becoming a different sort of person’. Drawing on the life stories of five participants and my own-lived experiences, the investigation is in part auto-ethnographical. It considers how reading and writing behaviours in English became the ‘constitutive’ components of ‘identity and personhood’ (Street 1994, p. 40). I utilised semi-structured life history interviews with young adult Cambodian participants, who spoke about how their individual and social performance of identity was influenced by their participation in English literacy practices and events in Cambodia. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/22/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/22/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid PGA Tour Golf PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Conference Quarterfinal: Teams TBA. (N) Å Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. NBA Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Baseball Dodgers at Houston Astros. (N) 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: STP 400. From Kansas Speedway in Kansas City, Kan. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program 22 Niños 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Simply Ming Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tú Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Paid Program Toonturama Presenta El Campamento de Papá › (2007, Comedia) (PG) Blankman ›› (1994) Damon Wayans. -

The American Dream

UNIT 1 The American Dream Visual Prompt: How does this image juxtapose the promise and the reality of the American Dream? Unit Overview In this unit you will explore a variety of American voices and define what it is to be an American. If asked to describe the essence and spirit of America, you would probably refer to the American Dream. First coined as a phrase in 1931, the phrase “the American Dream” characterizes the unique promise that America has offered immigrants and residents for nearly 400 years. People have come to this country for adventure, opportunity, freedom, © 2017 College Board. All rights reserved. and the chance to experience the particular qualities of the American landscape. G11_U1_SE_B1.indd 1 05/04/16 12:08 pm UNIT The American Dream 1 GOALS: Contents • To understand and define Activities complex concepts such as the American Dream 1.1 Previewing the Unit ..................................................................... 4 • To identify and synthesize a variety of perspectives 1.2 Defining a Word, Idea, or Concept ............................................... 5 • To analyze and evaluate the Essay: “Veterans Day: Never Forget Their Duty,” by effectiveness of arguments Senator John McCain • To analyze representative 1.3 America’s Promise ....................................................................... 9 texts from the American experience Speech: Excerpt from Address on the Occasion of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Statue of Liberty, by Franklin D. Roosevelt 1.4 America’s Voices ....................................................................... 12 ACADEMIC VOCABULARY Poetry: “I Hear America Singing,” by Walt Whitman primary source defend Poetry: “I, Too, Sing America,” by Langston Hughes challenge 1.5 Fulfilling the Promise ................................................................ 15 qualify Short Story: “America and I,” by Anzia Yezierska 1.6 Defining an American ............................................................... -

Eva Evdokimova (Western Germany), Atilio Labis

i THE CUBAN BALLET: ITS RATIONALE, AESTHETICS AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY AS FORMULATED BY ALICIA ALONSO A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Lester Tomé January, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Joellen Meglin, Advisory Chair, Dance Karen Bond, Dance Michael Klein, Music Theory Heather Levi, External Member, Anthropology ii © Copyright 2011 by Lester Tomé All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT In the 1940s, Alicia Alonso became the first Latin American dancer to achieve international prominence in the field of ballet, until then dominated by Europeans. Promoted by Alonso, ballet took firm roots in Cuba in the following decades, particularly after the Cuban Revolution (1959). This dissertation integrates the methods of historical research, postcolonial critique and discourse analysis to explore the performative and discursive strategies through which Alonso defined her artistic identity and the collective identity of the Cuban ballet. The present study also examines the historical context of the development of ballet in Cuba, Alonso’s rationale for the practice of ballet on the Island, and the relationship between the Cuban ballet and the European ballet. Alonso defended the legitimacy of Cuban dancers to practice ballet and, in specific, perform European classics such as Giselle and Swan Lake. She opposed the notion that ballet was the exclusive patrimony of Europeans. She also insisted that the cultivation of this dance form on the Island was not an act of cultural colonialism. In her view, the development of ballet in Cuba consisted, instead, of an exploration of a distinctive Cuban voice within this dance form, a reformulation of a European legacy from a postcolonial perspective. -

Viewers in the Audience

ABSTRACT In my project, I analyze the star text of María Félix (1914-2002). In spite of her prolific film career of 47 films and her memorable image in the media, the scholarly treatment of her films and larger star text has been limited. As vintage film magazines and Mexican melodramatic comics attest, Félix was very visible and her personal life was scrutinized as her “real-life” self played out characteristics from her mala mujer film persona—her multiple husbands and lovers, her relationship with her son, and even her wardrobe choices. I analyze many of her films and her image in other forms of media such as fotonovelas, trade magazines, and her biographical sources in the following chapters. Her star image is powerful and far-reaching and presents an alternative model of Mexican womanhood from the beginning of her film career in the 1940s through (and even beyond) her last film in 1970. The star text of María Félix is a site that registered tensions between modernity and the traditional at a particular moment in Mexican history. The Mexican Revolution of 1910 brought many changes to society as warfare destabilized the family and disrupted the region. After the war, the Revolution became institutionalized as the government attempted to put into practice the goals of the Revolution. From the 1940s and throughout 1950s and 1960s it was a time of increased ii industrialization and urbanization as people migrated to the cities to find employment, as it became increasingly difficult to support a family through farming. These social tensions registered in her films and star text are in relation to women’s changing roles as Mexican women gained more political freedoms, including national suffrage in 1953, and began working outside the home as the nation became more industrialized and urbanized throughout the 1940s and subsequent decades. -

Unlocking Your Dreams Course & Manual

Unlocking Your Dreams Course & Manual To order manuals, or the audio cd or mp3 teaching of Unlocking Your Dreams, or to schedule a dream seminar in your area contact: Autumn Mann 916 Idaho Ave SE Huron, SD 57350 605-352-9575 [email protected] Unlocking Your Dreams Course & Manual [Type text] Copyright 2010 by Autumn Mann. All rights reserved. Copying for the purpose of resale is prohibited. Copying of these materials for personal use is permitted. Unlocking Your Dreams Table of Contents Developing a Healthy Respect for Dreams……………………………………….1 Discerning a God Given Dream…………………………………………………….4 Created to Hear God’s Voice………………………………………………………..8 Biblical Types of Spiritual Dreams………………………………………………...9 Categories of Spiritual Dreams…………………………………………………….11 Steps to Dream Interpretation………………………………………………………13 Journaling Tips………………………………………………………………………..15 Understanding the Many Faces of God…………………………………………..16 Steps of Handling a Prophetic Word………………………………………………19 Stewardship: The Key to Increase in Dreams…………………………………..20 Tips for Remembering Dreams……………………………………………………..22 Tips for Receiving Dreams…………………………………………………………..23 Dream Sample Worksheets …………………………………………………………24 Breaking the Communication Box ………………………………………………...27 20 Most Common Dreams……………………………………………………………28 Scripture References on Dreams…………………………………………………..33 Dream Symbols & Language………………………………………………………..35 Dictionary of Symbols………………………………………………………………..37 Suggested Dream Resources……………………………………………………….50 [Type text] [Type text] Developing a Healthy Respect for Dreams - God is always speaking and those with a tender heart have the privilege of hearing his voice. God is a supernatural God who communicates with His people through supernatural means! For Example: o Bible refers to angels over 300 times. o Bible refers to “dreams” or “visions” or their variations over 200 times. o Very little difference in the Hebrew language and culture between dreams and visions.