Michèle Mertens Graeco-Egyptian Alchemy in Byzantium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Book Reviews

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 35, Number 2 (2010) 125 BOOK REVIEWS Rediscovery of the Elements. James I. and Virginia Here you can find mini-biographies of scientists, R. Marshall. JMC Services, Denton TX. DVD, Web detailed geographic routes to each of the element discov- Page Format, accessible by web browsers and current ery sites, cities connected to discoveries, maps (354 of programs on PC and Macintosh, 2010, ISBN 978-0- them) and photos (6,500 from a base of 25,000), a time 615-30793-0. [email protected] $60.00 line of discoveries, 33 background articles published by ($50.00 for nonprofit organizations {schools}, $40.00 the authors in The Hexagon, and finally a link to “Tables at workshops.) and Text Files,” a compilation probably containing more information than all the rest of the DVD. I will discuss this later, except for one file in it: “Background Before the launching of this review it needs to be and Scope.” Here the authors point out that the whole stated that DVDs are not viewable unless your computer project of visiting the sources, mines, quarries, museums, is equipped with a DVD reader. I own a 2002 Microsoft laboratories connected with each element, only became Word XP computer, but it failed. I learned that I needed possible very recently. Four recent developments opened a piece of hardware, a DVD reader. It can be installed the door: first, the fall of the Iron Curtain allowing easy inside the computer or attached externally. The former is access to Eastern Europe including Russia; second, the cheaper, in fact quite inexpensive, unless you have to pay universality of email and internet communication; third, for the installation. -

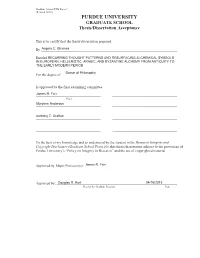

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES NUMBER 7 Editorial Board Chair: Donald Mastronarde Editorial Board: Alessandro Barchiesi, Todd Hickey, Emily Mackil, Richard Martin, Robert Morstein-Marx, J. Theodore Peña, Kim Shelton California Classical Studies publishes peer-reviewed long-form scholarship with online open access and print-on-demand availability. The primary aim of the series is to disseminate basic research (editing and analysis of primary materials both textual and physical), data-heavy re- search, and highly specialized research of the kind that is either hard to place with the leading publishers in Classics or extremely expensive for libraries and individuals when produced by a leading academic publisher. In addition to promoting archaeological publications, papyrolog- ical and epigraphic studies, technical textual studies, and the like, the series will also produce selected titles of a more general profile. The startup phase of this project (2013–2017) was supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also in the series: Number 1: Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy, 2013 Number 2: Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal, 2013 Number 3: Mark Griffith, Greek Satyr Play: Five Studies, 2015 Number 4: Mirjam Kotwick, Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Text of Aristotle’s Meta- physics, 2016 Number 5: Joey Williams, The Archaeology of Roman Surveillance in the Central Alentejo, Portugal, 2017 Number 6: Donald J. Mastronarde, Preliminary Studies on the Scholia to Euripides, 2017 Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity Olivier Dufault CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES Berkeley, California © 2019 by Olivier Dufault. -

Alchemy Journal Vol.6 No.2.Pdf

Alchemy Journal Vol.6 No.2 Vol.6 No.2 Summer 2005 CONTENTS ARTICLES Alchemical Art: Blue Gold Alchemical Art: Blue Gold The Gnostic Science by Kattalina M. Kazunas of Alchemy 2 (Note: Large images will take time to load. Hit the "Refresh" button on your browser if no images appear.) The Great Alchemical Work FEATURES From the Fire New Releases Announcements Feedback EDITORIAL From the Editor Submissions Subscriptions Resources Return to Top In the dim pre-history of mankind, a god- like race of beings inter-bred with humanity and taught them creative and generative forms of cultural wisdom. The first human master of this science codified the canon of its knowledge (wrote the book on it we might http://www.alchemylab.com/AJ6-2.htm (1 of 21)7/30/2005 8:06:48 AM Alchemy Journal Vol.6 No.2 say) from which the children of gods and men built an advanced civilization. That which is Below corresponds to that which is Above, and that which is Above corresponds to that which is Below, to accomplish the miracles of the One Thing. ARTICLES Alchemical Art: Blue Gold The Gnostic Science of Alchemy 2 The Great Alchemical Work FEATURES From the Fire New Releases Announcements Feedback EDITORIAL From the Editor Submissions Subscriptions Resources Return to Top I felt the desire to create a series of broadsides that were http://www.alchemylab.com/AJ6-2.htm (2 of 21)7/30/2005 8:06:48 AM Alchemy Journal Vol.6 No.2 a contemporary interpretation of ancient alchemical ideas. -

FROM MEDIEVAL LEGEND to MAD SCIENTIST Theodore Roszak

Anarchic alchemists: dissident androgyny in Anglo-American gothic fiction from Godwin to Melville Leeuwen, E.J. van Citation Leeuwen, E. J. van. (2006, September 7). Anarchic alchemists: dissident androgyny in Anglo- American gothic fiction from Godwin to Melville. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4552 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4552 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). &+$37(5 7+($/&+(0,67 )5200(',(9$//(*(1'720$'6&,(17,67 Theodore Roszak writes that “magic has not always belonged to the province of the carnival or the vulgar occultist” (Roszak, &RXQWHU&XOWXUH 241). However, magic, alchemy and witchcraft, since the coming into dominance of a scientific rationalist ideology, have been often repressed, sometimes illegitimate and at best marginal practices and modes of thought in Western society. As a consequence, the legendary figures associated with these mystical arts – sorcerers, alchemists, witches and druids – in the course of the eighteenth century, found their most welcome home in cultural productions that deal with the fantastic, the unreal, and the culturally abject. The figure of the alchemist, the subject of this chapter, is a cultural figure in which Hermetic philosophy, folkloric magical practices and a pre-scientific naturalist worldview combine. In cultural productions since the renaissance, the figure has been a powerful cultural symbol for the mystical, supernatural and occult, both on the level of fact and affect, of argument and spectacle.1 It is not so surprising then that during the age of enlightenment the alchemist emerged as a popular stock figure in a genre of fiction that embraced residual cultural elements such as folklore, mysticism, magic and the supernatural: the gothic. -

Renaissance Magic and Alchemy in the Works of Female Surrealist Remedios Varo

RENAISSANCE MAGIC AND ALCHEMY IN THE WORKS OF FEMALE SURREALIST REMEDIOS VARO ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Dominguez Hills ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Humanities ____________ by Tammy M. Ngo Fall 2019 THESIS: RENAISSANCE MAGIC AND ALCHEMY IN THE WORKS OF FEMALE SURREALIST REMEDIOS VARO AUTHOR: TAMMY M. NGO APPROVED: ______________________________ Patricia Gamon, Ph.D Thesis Committee Chair ______________________________ Kirstin Ellsworth, Ph.D Committee Member ______________________________ Kimberly Bohman-Kalaja, Ph.D Committee Member Dedicated to Professor Lawrence Klepper ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my special thanks of gratitude to my advisor Professor Patricia Gamon, Ph.D., Humanities, Art History. In addition, to my family and friends who supported me during my thesis research, thank you. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... IV TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ V LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... VI ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... X 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................1 -

Final Copy 2020 05 12 Leen

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Leendertz-Ford, Anna S T Title: Anatomy of Seventeenth-Century Alchemy and Chemistry General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. ANATOMY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ALCHEMY AND CHEMISTRY ANNA STELLA THEODORA LEENDERTZ-FORD A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, School of Philosophy. -

Visualization in Medieval Alchemy

Visualization in Medieval Alchemy by Barbara Obrist 1. Introduction Visualization in medieval alchemy is a relatively late phenomenon. Documents dating from the introduction of alchemy into the Latin West around 1140 up to the mid-thirteenth century are almost devoid of pictorial elements.[1] During the next century and a half, the primary mode of representation remained linguistic and propositional; pictorial forms developed neither rapidly nor in any continuous way. This state of affairs changed in the early fifteenth century when illustrations no longer merely punctuated alchemical texts but were organized into whole series and into synthetic pictorial representations of the principles governing the discipline. The rapidly growing number of illustrations made texts recede to 1 the point where they were reduced to picture labels, as is the case with the Scrowle by the very successful alchemist George Ripley (d. about 1490). The Silent Book (Mutus Liber, La Rochelle, 1677) is entirely composed of pictures. However, medieval alchemical literature was not monolithic. Differing literary genres and types of illustrations coexisted, and texts dealing with the transformation of metals and other substances were indebted to diverging philosophical traditions. Therefore, rather than attempting to establish an exhaustive inventory of visual forms in medieval alchemy or a premature synthesis, the purpose of this article is to sketch major trends in visualization and to exemplify them by their earliest appearance so far known. The notion of visualization includes a large spectrum of possible pictorial forms, both verbal and non-verbal. On the level of verbal expression, all derivations from discursive language may be considered to fall into the category of pictorial representation insofar as the setting apart of groups of linguistic signs corresponds to a specific intention at formalization. -

Alchemy Endnotes(1)

A C A P P E L L A Title: ALCHEMY Artists: Kamilla Bischof, Hélène Fauquet, Till Megerle, Evelyn Plaschg curated by: Melanie Ohnemus Venue: Acappella Vico Santa Maria a Cappella Vecchia 8/A, Naples Opening: October 11, 2018 Till: December 8, 2018 www.museoapparente.eu [email protected] \\ +39 3396134112 Alchemy (from Arabic “al-kīmiyā”) is a philosophical and protoscientific tradition practiced throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia. It aims to purify, mature, and perfect certain objects (1). Common aims were crysopoeia (2), the transmutation of “base metals” (e.g., lead) into “noble metals” (particularly gold); the creation of an elixir of immortality; the creation of panaceas (3) enabling to cure any disease; and the development of an alkahest, a universal solvent. The perfection of the human body and soul was thought to permit or result from the alchemical magnus opus and, in the Hellenistic and western tradition, the achievement of gnosis (5).(6) In Europe, the creation of a philosopher’s stone was variously connected with all of these projects. In English, the term is often limited to descriptions of European alchemy, but similar practices existed in the Far East, the Indian subcontinent, and the Muslim world. In Europe, following the 12th-century Renaissance, produced by the translation of Islamic works on science and the Recovery of Aristotle, alchemists played a significant role in early modern science (particularly chemistry and medicine). Islamic and European alchemists developed a structure of basic laboratory techniques, theory, terminology, and experimental method, some of which are still in use today. However, they continued with the ancient belief in four elements and guarded their work in secrecy including cyphers and cryptic symbolism. -

Al-Kimya Notes on Arabic Alchemy Chemical Heritage

18/05/2011 Al-Kimya: Notes on Arabic Alchemy | C… We Tell the Story of Chemistry Gabriele Ferrario Detail from a miniature from Ibn Butlan's Risalat dawat al-atibba. Courtesy of the L. Mayer Museum for Islamic rt, $erusalem. Note: Arabic words in this article are given in a simplified transliteration system: no graphical distinction is made among long and short vowels and emphatic and non-emphatic consonants. The expression —Arabic alchemy“ refers to the vast literature on alchemy written in the Arabic language. Among those defined as —Arabic alchemists“ we therefore find scholars of different ethnic origins many from Persia who produced their works in the Arabic language. ccording to the 10th-century scholar Ibn l-Nadim, the philosopher Muhammad ibn ,a-ariya l-Ra.i /0th century1 claimed that 2the study of philosophy could not be considered complete, and a learned man could not be called a philosopher, until he has succeeded in producing the alchemical transmutation.3 For many years Western scholars ignored l-Ra.i4s praise for alchemy, seeing alchemy chemheritage.org/…/25-3-al-kimya-not… 1/3 18/05/2011 Al-Kimya: Notes on Arabic Alchemy | C… instead as a pseudoscience, false in its purposes and fundamentally wrong in its methods, closer to magic and superstition than to the 2enlightened3 sciences. Only in recent years have pioneering studies conducted by historians of science, philologists, and historians of the boo- demonstrated the importance of alchemical practices and discoveries in creating the foundations of modern chemistry. new generation of scholarship is revealing not only the e7tent to which early modern chemistry was based on alchemical practice but also the depth to which European alchemists relied on rabic sources. -

Hitherto Unnoticed Coptic Papyrological Evidence for Early Arabic Alchemy*

chapter 10 The Master Spoke: “Take One of ‘the Sun’ and One Unit of Almulgam.” Hitherto Unnoticed Coptic Papyrological Evidence for Early Arabic Alchemy* Tonio Sebastian Richter Dedicated to the memory of Holger Preissler(1943–2006), in gratitude, admi- ration, and affection for an eminent Arabist, a truly humanistic scholar, and a teacher in the best sense! ∵ Prolegomena: A Brief Account of Earlier Approaches to Coptic Alchemical Manuscripts A legend transmitted in the Kitāb al-fihrist of Abū al-Faraj Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq al-Nadīm tells the story of the first translation of alchemical writings into Arabic, focusing on the figure of the Umayyad prince Khālid ibn Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya, “who used to be called the ḥakīm of the Marwān family. Being noble-minded and deeply enamoured of the sciences, particularly the alchem- ical arts, he ordered a number of Greek philosophers living in the town of Miṣr, * During my work on Coptic alchemical texts, I enjoyed the aid of a number of colleagues. It is a pleasant duty to express my gratitude to Susanne Beck, Charles Burnett, Stephen Emmel, Bink Hallum, Thomas Hofmeier, Wilferd Madelung, James Montgomery, Peter Nagel, Holger Preißler †, Fuat Sezgin, Emilie Savage-Smith, Petra Sijpesteijn, and Manfred Ullmann for their advice. A number of lectures helped me to develop and improve my thoughts on the topic as a whole, and on particular aspects of it. The talk presented at the 3rd conference of the International Society for Arabic Papyrology in Alexandria (March 2006) was the first occasion to receive questions and comments from a larger audience.